Higher music (Educ)ACTION in Southeastern Brazil: Curriculum as a Practice and Possibilities for Action in (De)colonial Thought

[1]

EURIDIANA SILVA SOUZA

Universidade Federal de Minas de Gerais/ Fábrica de Artes

Belo Horizonte, Brazil

[Translated by Helena Perez Coelho]

September 2019

Published in Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 18 (3): 85–114 [pdf]

https://doi.org/10.22176/act18.3.85

This text stems from documentary analysis of the content of the official curriculum and from questionnaires taken by former graduates of four bachelor’s degree programs in music offered in higher education institutions in the Southeastern region of Brazil. Following the analysis, I propose reflections on the following: the concept of curriculum as a practice and on the policies for curricular flexibilization; the ideas of music and society that rule the analyzed curricula and how these ideas relate to the comprehension of professional training in music; the realities and possibilities of action for (de)colonial thought present in the formation of the curricula; and finally, the agency of the subjects who set the curricula in action. Such reflections reveal the maintenance of Eurocentric colonial values in the training of graduates, as well as an openness to other career paths. Furthermore, they establish higher music education as a field of possibility for epistemic magnification, supported by curricular flexibilization and by political projects of university expansion, in addition to becoming a field of action to social prophylaxis.

Keywords: Higher music education; curriculum as practice; coloniality and decoloniality; curricular flexibilization in Brazil; bachelor’s degree in music

The proposition to reflect on higher music (educ)ACTION stems from a linguistic provocation that aims to reveal the dimension of action, practice, and praxis within the processes of teaching-learning in higher education in music.[2] This play on words takes education in its “problematizing” dimension by way of a “preoccupation with people as beings in the world and with the world; preoccupation with what and how they are ‘being’” (Freire 2015, 100).

The problematizations presented herein depart from the notion that music, as a social and relational practice, occupies any spaces in a multitude of actions and concepts. However, as a legitimized object of study in higher education institutions, music is mostly defined under the weights of the Eurocentric colonial tradition.

Coloniality, as Shifres and Rosabal-Coto (2017) appropriately pinpoint with support by Quijano (2000), is a logic of thought based on the ontology of the ideal model of human being of the European modernity. Through the coloniality of knowledge (Lander 2005) and power (Quijano 2005), this conqueror and excluding logic has defined, and still defines, who knows and who is capable of knowing within society. “The coloniality of knowledge reveals … an epistemological legacy of Eurocentrism that prevents us from understanding the world based on the world itself and understanding the epistemes that are its own” (Porto-Gonçalves 2005, 3, author’s italics).

In music, and mainly in higher music education in Brazil, coloniality may be witnessed through the reproduction of the European conservatory system, not only in its teaching practices, but especially in the definition of the object to be taught—classical/erudite/concert music. Ideals of music as an “object to be contemplated, distanced from the subject that performs it or takes part in its construction” are perpetuated through a practice that “classifies what music is or is not; who can be a musician and who cannot, thereby determining hierarchical roles for people who participate in different musical experiences—composer, performer and audience” (Shifres and Rosabal-Coto 2017, 86). Music as object/product carries teaching-learning relations that replicate past practices. This fact hinders the creation of an identity for local music (Woodford 2002) and promotes the maintenance of a conservatorial habitus (Pereira 2013, author’s italics)[3] that is built and rebuilt within its condition of structured structure (Bourdieu 2008) of hegemonic thought.

This hegemony of colonial thought culminates in “strategies to oppress and silence in various ways” (Miglievich 2014, 67), such as possibilities of who to be, of being capable, of existing, and of knowing. These strategies override alterity in the name of homogeneity, which is hierarchically dictated from top to bottom —from a political-economical North to a dependent and subordinate South (Kummu and Varis 2011; Grosfoguel 2013). The decolonial movement arises as a “theoretical-practical, political and epistemological resistance to the logic of modernity/coloniality” (Ballestrin 2013, 105). This movement offers a contraposition to the tendency toward division between the Global North and South. “In this regard, it is revealing that the efforts of theorization in Brazil and Latin America may fit the label of ’thought’ instead of ‘social and political theory’” (Ballestrin 2013, 108–9). This thought lays bare the abyssal differences (Santos 2007) between European conceptions and Latin American praxis.

Utilizing such theoretical framework, this text emerges from a research process in comparative education and offers a reflection on the following questions: a) What are the epistemological concepts of musical practice and culture that rule the official curricula in higher music education in the Southeast of Brazil? b) By establishing curriculum as a practice and taking into consideration the multiple confluences of the musical knowledge and the existence of (de)colonial thought,[4] what are the possibilities for action within the curriculum or for a curriculum in action when it comes to reproduction or epistemic innovation?

This text is structured in four parts. The first part presents the context for the research and the methodology behind the reflection. The second part briefly reviews the literature containing the concepts of curriculum as a dialogical practice amongst all agents who comprise the scenario of education:

The development of this notion of curriculum as practical scope has the attractive ability to classify, around such discourse, the functions the curriculum fulfills and how it does them, studying it procedurally: it is expressed through a practice and acquires meaning inside a practice…. It is the context of the practice at the same time that is contextualized by it. (Sacristán 2000, 16)

The third part presents the higher education institutions (HEI) selected for the study and includes excerpts of their curricular texts. They are envisioned under a processual perspective, analyzing the epistemic concepts of music and culture, which are revealed as choices/political positionings of the institutions and of the subjects who constitute them.

The fourth part highlights the issue of a “broad, critical and reflective training,” stressed as a goal for the graduates in music. What would broad, critical, and reflective be? What kind of (de)colonial thought can be contemplated? The parentheses here are used as a tool to refer to two possibilities: 1) the turn to decolonial thought, a thought that is different and belongs to the different, a thought of other forms of knowledge and musical practices; 2) a possible—and perhaps likely—maintenance of coloniality. This is due to the fact that, on one hand, the academic space of higher education stimulates reflection and criticism over theories and practices, but on the other hand, it provides the maintenance of the social distinction of judgment (Bourdieu 2008) and of the colonial difference. This difference in the/of the colonial/modern world is also where “Westernism” was articulated as the dominant idea of the modern colonial world (Mignolo 2003, 10).

In the conclusion, teachers and students are presented as the agents of curricular practice. The curriculum is conceived here as practice of the documents which select and legitimize the way institutions understand music and culture. It is also conceived within its agency, transcending the role where it is sheltered, being carried out humanely in the relations of the classrooms and of life. Through this view, I present the curriculum as a tool for a preventive action to the social field. The curriculum design can contribute to a better professional and human training. It is a kind of prophylaxis in the social well-being which may give voice to the silenced, allow one to hear the resistances, and thus promote good living (Santos 2004). This involves a curriculum that reveals the “action” present in the term (educ)ação, as a conscious assumption of choices, a curriculum that reveals and facilitates different projects in higher music education and in the professional training of musicians. After all, we are not built of European roots only—we are built of a multiplicity of roots that were left in limbo. We are heterogeneous, and we need

everyone to understand that the purpose of a programme in music education [and in higher musical education] is much bigger than offering an option of a job [and training for a job]—it is about an option for existence; it is about a radical move against homogenization, about life forwarding; it is about an existence dedicated to questioning, to the creative anguish, to the non-conformity, to the possibility of transformation, to the appreciation of life in an intense and violently artistic way. (Caznok 2013)

The Southeastern region of Brazil: the context and the methodology of the study on the bachelor’s degrees in music

The southeastern region of Brazil is composed of the states of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais, and Espírito Santo. These states comprise the highest demographic and economic indexes[5] in the country, which directly affect opportunity and access to public and private higher musical education. This is verified by the number of registered HEI in this region—greater than the sum of those in all remaining regions of the country.[6] In addition, the developed labor market in music is ever expanding, with diverse possibilities and market niches. There are differences in percentage and statistical analysis between the Southeast and other Brazilian macro regions, which supports my decision to analyze this region. Moreover, the Southeast is the region in which I live, which facilitated access to such realities, presented not only as external data but also as part of my own experience as a professional working in the area.

The Southeast has a wide variety of social and cultural musical practices. This is represented by the coexistence of indigenous peoples[7] (Tugny 2015), Quilombola communities[8] (Dempsey 2017; Lucas 2002), communities from different religious matrices (Moraes 2018), and communities in the country’s largest favelas (Anacoana 2012)—where rap (Garcia 2013), funk (Palombini 2013), samba and rock (Aredes 2015) coexist, either in their mass-driven or lower-circulation versions, revealing processes of cultural resistance.

The aforementioned research is found in ethnomusicology studies and among the approximations between music and social sciences. These areas have alterity as a legitimized principle and as a diverse possibility in which to be in this world. Music education, in its approximations and dialogues with ethnomusicology and sociology, has turned its eyes towards diversity, towards different teaching-learning possibilities, and towards awareness of the weight of the European tradition (Arroyo et al. 2003; Fragoso 2018; Green 2014; Nettl 2010); however, how do these concepts of alterity present themselves in higher music education and in the training provided within the bachelor’s degree in music?

The necessity to question the bachelor’s degree in music inside the system of higher education is justified by the scarcity/frequent interruption of the studies. These facts directly problematize the courses on their pedagogical construction (Louro 1997, 1998; Louro and Souza 1999) or on their peculiarities amidst the dynamics of public higher education in Brazil. The bachelor’s degrees, par excellence, replicate the conservatory model within the academic system. This model not only reproduces Eurocentric colonial principles but also generates controversial issues related to the administration of higher education systems.[9] These courses urgently need to be envisioned beyond the notion of “their traditional ‘hot house’ concentration on the exclusive training of performers and instead develop a more flexible and realistic curriculum” (Bennett 2008) so as to be responsive to the students’ cultural context.

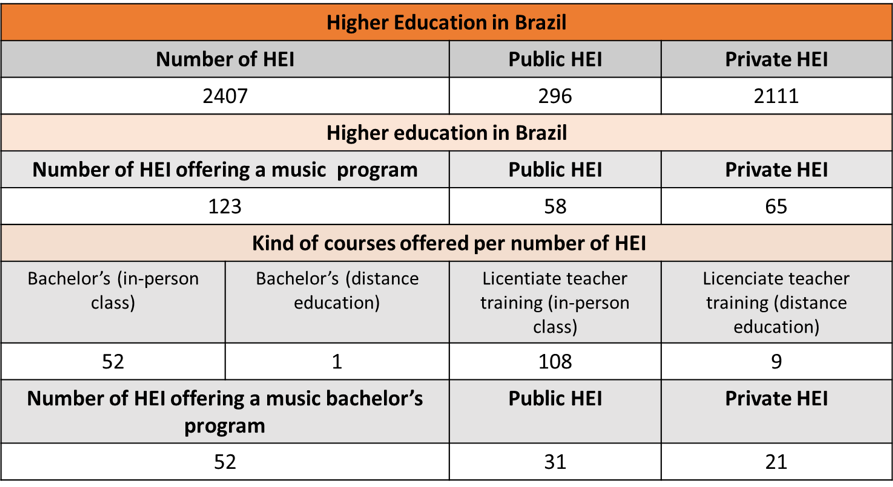

Table 1: Higher music education in Brasil

Table 1: Higher music education in Brasil

Source: Cross data of Higher Education Census (INEP 2016) and e-MEC database

Figure 1: Distribution of bachelor’s music programs in Brazil

Source: e-MEC database

To provide background for the proposed reflection, I present data collected between the years of 2016 and 2018, part of the corpus of my PhD research.[10] This paper is based on the analysis of four public HEIs, one for each state’s capital: University of São Paulo (USP), Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), University of Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), and Faculty of Music of Espírito Santo (FAMES).

The documents analyzed were collected from the HEI’s websites—pedagogical projects, syllabi,[11] and curriculum of the programs—and from online questionnaires taken by 42 graduates of these institutions (n=42). The data was analyzed according to its content. After thoroughly reading the pedagogical projects, their contents were bundled into categories by such themes as description of the object to be taught (music), conception of vocational training, profile of the graduates, historical and social contextualization of the course/profession, and curricular flexibilization/mobility. The curricula were analyzed according to the proportion of mandatory subjects, electives, and other forms of credit. The links between the texts of the projects and the curricula were made by approximation of their semantic content and through more direct connections regarding general subject areas (performance, education, musical analysis and structuration, and history). The questionnaires were divided into three main themes (pre-training, training, and post-training integration to the labor market). The answers were computed quantitatively when the questions showed prior choices of answer (percentage mapping) or by cluster analysis in open answer questions (Hair Jr. 2009). The categories of analysis surfaced according to word repetition (synonyms and correlates) and were considered within a broader analytical framework in the scope of the research.

2. Curricula as practice document

I depart from the definition of curriculum as a “project that legitimizes culture; a project which is cultural, social, political and administratively conditioned and fulfils the school’s activity, becoming reality within the conditions of the school as it is set up” (Sacristán 2000, 35, author’s italics). This definition is problematic; it emphasizes the non-neutrality of choice in the construction of texts, curricular grades, and course syllabi—a non-neutrality not only on paper but also in the agency of the curriculum as a practice. The curriculum cannot consider a simplistic consciousness in which life is “practical,” as it belongs to the practical-utilitarian order (Sánchez Vásquez 2011). Within the curriculum, praxis is understood as the “foundation of knowledge.”

If man only knows the world to the extent that it is the object/product of their activity and if, furthermore, they only know it because they act practically upon it and due to their real and transformative activity, it means that the problem of the objective reality … is not a problem that can be solved theoretically, in a mere theoretical confrontation between our concept and the object, or between my thought and other thoughts…. If you want to show your truth, you have to leave and mould yourself, take shape in reality itself, in the form of practical activity. (Sánchez Vásquez 2011, 148)

I am aware that practice does not speak for itself; educational researchers have to analyze and interpret facts and practices from a theoretical perspective. Therefore, I see eye to eye with Sacristán’s (2000) punctuation of three issues in the concept of curriculum as a practice. The first issue is that the student’s learning process is organized in consonance with a cultural project, in effect through the selection and singular encoding of the contents perceived as necessary or pertinent. The second issue highlights that the curriculum is conducted within certain political, administrative, and institutional conditions. These conditions mould and bring within themselves the hidden dimension of the curriculum: values and practices which are not explicit in written text but are manifested in physical and conceptual form in education institutions. The third issue implicates the social sphere in which curricular decisions are made so as to be fulfilled within the school field. From this social sphere, curricular philosophies are defined to synthesize philosophical, epistemological, scientific, pedagogical, and social value positionings.

When connecting the three issues aforementioned to higher music education in Brazil, I point to the following findings/reflections:

1) What is considered necessary and pertinent in higher music education in Brazil is still rooted in the absolute value of European music. As Pereira reported, “the habitus conservatorial ultimately implants in individuals an aesthetic of superiority of erudite music based on an autonomy of the social context, disregarding delineations and overvaluing the inherent meanings to be studied” (Pereira 2013, 255). Therefore, music, perceived as value in itself, as legitimized work or art, is placed in curricular documents removed from its context of production and circulation. Curriculum does not problematize “organization of the musical practice, thus neglecting cultural processes that produce meanings and influence the approximation between individuals and music” (255).

2) The political scenario in Brazil has shifted quickly, revealing a lack of state policies and the fragility of government policies. The laws, the regiments that guide the practices of the HEI, and the financing conditions of teaching and research have changed frequently. From the policies that directly affect higher education curricula, I emphasize curricular flexibilization, which was discussed and implemented in Brazil in the 1990s. This change, inserted into a movement of adjustment between academic training and the labor market, proposes the “idea of curricular flexibility” as a possibility of “harmony with life and with employability” (Catani, Oliveira, and Dourado 2001, 72). This curricular amendment allows students to conduct their training within a grid of mandatory and elective disciplines. In addition, it facilitates greater transit of students among academic units in the university, depending on the curricular project adopted by each institution. These multidirectional processes of training undertake different classifications, but they generally converge to majors or minors. These types of training intend to increase the diverse capitals acquired within the training in higher education, developing students’ autonomy and protagonism.

3) Taking into consideration that curricular policies reflect the social and historical sphere in which they are developed, curricula may be more than just a reproduction of values of other lands and minds. Curricula may (perhaps must) become an effective practice for dialogue with reality. It may serve not only as a set of tools and techniques needed in musical training, but as an update to the space-time in which it is held, with an “ethical responsibility” also for carrying a concept of world. Curricula may allow beings who take part in its practice to be “conditioned, but not determined,” acknowledging that “history is a time of possibility, not a time of determinism,” and that present and future are “problematic and not inexorable” (Freire 1996, 21, author’s italics).

Following these problematizations, by crossing content and context, I emphasize two founding concepts of the documents that define higher education curricula in music—music and culture—music as content and main object of the course, and culture (in society) as the context in which content and pathways are developed. After a brief characterization of the HEIs selected for this study, I will compare how these two instances overlap in the definitions of what is considered “good” professional training of musicians.

3. Curricular concepts of music and culture in four Southeastern Brazilian HEIs

Table 2 describes the four HEI selected for this study.[12]

Table 2—Description of the HEI

Table 2—Description of the HEI

The type of administration in each of these HEIs directly affects their curricular concepts and even their autonomy. UFMG and UFRJ are Federal Institutions of Higher Education (IFES), meaning that they are administered by the Union and respond directly to the National Council of Education and to the Ministry of Education. These institutions also have internal guidelines dictated by their highest authorities. On the other hand, USP and FAMES are state institutions administered by the provinces’ local governments—which respond to the national guidelines and to their state’s specific regulations. This fact is relevant, because state institutions do not necessarily undergo the same policies of higher education created directly for the IFES. As an example of such policies, REUNI (Restructuration and Expansion of Federal Universities) has expanded the opening of vacancies and enabled the creation of new bachelor’s degrees such as music therapy and popular music. The program has also facilitated the processes of curricular flexibilization.[13]

The decision to comparatively study federal and state institutions was not predetermined but contingent, because the state of São Paulo does not have an IFES that offers courses in music, and the UFES (Federal University of Espírito Santo) offers only teacher training in music and one bachelor’s course. Nonetheless, this condition enriches the research process in comparative education.

Dominique Groux (1997) says that comparative education has a meaning. It is never free of cost. When rigorously done, the interpretation of similarities and differences related to any issue provides more interesting information than those derived from the interpretation of the same issue in a single context. (Ferreira 2008, 125)

Table 3—Bachelor’s degree qualification per HEI

Table 3—Bachelor’s degree qualification per HEI

The following paragraphs offer my analysis of excerpts from pedagogical projects of the HEIs presented. The analysis focuses on the concepts of music and culture that guide the training offered by the HEI, thus elucidating what each of them finds necessary and pertinent.

Music

Music, a diverse concept/practice widely discussed throughout history, appears in the curricular texts under different perspectives, ranging from object/product/practice within culture and as culture (Merriam 1964, Elliot 1995).

The text from FAMES rebuilds the history of Western music, beginning from ancient Greece and arriving in the colonization of Brazil. It points to the Portuguese enculturation of the Indigenous, yet it does not mention the presence of Black people in the construction of the country. By emphasizing music as “the practice of experts,” the text reveals the Western and Eurocentric legacy of the musical concept and practice. Although a situated social practice, music is still thought of as an autonomous construct. It is perceived as a symbolic imposition and not necessarily as a relational construction, since the “different”—the Indigenous, the unmentioned Black, the “primitive”—were defeated by a “superior” culture.

With the arrival of the Portuguese and the Jesuits, religious music and the rhythms of the Portuguese were introduced, thus starting the acculturation of the Indians by the molds of Portugal. Among the primitive people of Brazil and of other parts of the world, musical practice was left to the expert musicians. They were the ones capable of conveying the secrets of their craft to the individuals to whom they would pass on their posts. (FAMES 2011, 5)

Despite being short, the following text from USP emphasizes the academy and the concert, which constitute the epistemic basis for legitimization of the traditionally European musical practice.

Since its founding, the bachelor’s course offered by CMU-ECA-USP has been driven to improve creative, technical, theoretical and reflective skills. It is aimed at musicians who wish to orient their careers towards the activities of creation/concert, or the academic field, which involves research, teaching, musical creation and interpretation. (USP 2018)

The text from UFRJ stresses the maintenance of a musical practice and emphasizes modernity, the core of the constitution of colonial thought. The text highlights the historical and the contemporary in Eurocentric perspectives. The contemporary concert music, based on the avant-garde movements , are mostly present in the analysis of the syllabi of the disciplines offered by this institution.

The structure of this project comprises a set of disciplines more explicitly grounded in the traditions of theory and praxis of the classical-romantic music of the modernity, as well as disciplines which address Brazilian musical traditions and the production of contemporary culture. (UFRJ 2008, 7)

The text from UFMG develops a magnified view of the musical practice. It is removed from the dimension of the specialists and brought to the wider dimension of human practice. Music is perceived as a way to produce culture, rather than strictly as a cultural product. Thus, everyone becomes a musician in potential, “since we can all hear and be somehow sensitive to music. Listening is already part of the musical event” (UFMG 2011, n.p.). This concept of music optimizes the agency of music in society. “Through the musical practices, we can study human behavior, mass movement phenomena, hearing and sound transmission devices, religions and their communication dynamics, the mechanisms of belonging to social groups” (n.p.).

When analyzing the curricular documents, coincidentally (or not), it is possible to infer that the curricular project which presents the most Westernized and rigid concept of music is also the one which presents less mobility and openness within student training. In FAMES, for some qualifications, there is no option for electives, thus locking down the curricular grid. Likewise, the course with the widest perception of music is also the one which allows for more extended training, enabling students to go through different courses that enrich their professional practice and general education.

Culture

When considering culture as a tool, as proposed by Yúdice (2013), some terms deserve distinction within the field of perception of culture allied to curricular construction. Highlights of the text from UFMG are the terms plural and dynamic, which qualify the cultural market

as the result of a historical process that has gradually extended the scope of higher music training. The bachelor’s course of the Music School of UFMG not only focuses on the technical improvement of the musicians but also takes it as a starting point, aiming to capacitate the student … as to have a global and critical view of the musical phenomenon in the contemporary world, giving them conditions to intervene with greater autonomy in the extremely plural and dynamic process that characterizes the cultural market today. (UFMG 2011, n.p.)

As culture (resource), music has long been subjected to the logic of product-consumption, the logic of capital—whether symbolic or mercantile—as Bourdieu (2008) and Yúdice (2013)[14] have explained. It is my interest, however, to emphasize awareness of the plural and procedural condition in which music as a market is developed. If there are plural and dynamic conditions, there is possibility for variation, for other thoughts and practices.

The text from UFRJ underlines the possibility of someone else, based on concepts that consider a multifaceted, diverse, and contradictory contemporaneity. The text points to a process of globalization that is “not just about mass culture, which has already been fully developed and consolidated since the middle of the twentieth century, but is about a culture of fragmentation, of indeterminacy and entropy” (UFRJ 2008, 7). In this context, the training of the professional musician justifiably transitions between the technical-processual know-how and its applications on the market. It takes into consideration “the development of an aesthetic intelligence and the elaboration of spatial-temporal concepts such as rhythm, such as the new technologies of diffusion and consumption, the development of creativity as a critical and creative instance, among other aspects” (7), therefore promising an amplified training that “gives the future bachelor in music the necessary attributes for their professional backing in an market increasingly demanding of quality and technical breadth, which may reach the scope of culture, citizenship and the independence of thought” (UFRJ 2008, 7).

Fragmentation and indeterminacy may be inferred as the break of a homogeneous thought, as the questioning of a unique legitimation—whether of music, knowledge, politics, society, culture, world order…. Yet entropy, which, according to the laws of thermodynamics involves disorder and absence of regulation, is also directly related to the “amount of possible macro states” (Herscovici 2005), i.e. of the amount of different arrangements of a system. Still, there are questions remaining with no answer: do these highlighted terms attributed to culture refer only to an objective observation of disparity, or do they bring within them some nostalgia of homogenizing thought? Even though there is awareness of social heterogeneity, punctuated by entropy, is there practical action regarding appreciation of difference? Is it possible to have diverse confluences? How are the students in bachelor’s programs trained among the weight of the Eurocentric coloniality and among the multiple existences and subjects of their reality?

4. A broad, critical and reflective formation—possibilities for (de)colonial action

According to Resolution #2 of the CNE, which regulates the bachelor’s courses in music in Brazil,

[t]he bachelor’s course in music must promote, as the desired profile of the graduate, the qualification to possess reflective thought; an artistic sensibility; the use of compositional techniques; the mastery of knowledge regarding the compositional manipulation of acoustic, electroacoustic, and other experimental means; an aesthetic sensibility acquired through knowledge of styles, repertoires, artworks and other musical creations, thus revealing indispensable skills and aptitudes for professional activity within society, within the artistic, cultural, social, scientific and technological dimensions, inherent to the area of music. (CNE 2004)

In a fairly brief way and in consensus with this resolution, the curricular text aims to offer to students who take part in its practice a broad, critical, and reflective training. FAMES’ mission is

to promote the formation of musicians who are capable of participating in the fields of their musical training as efficient connoisseurs and executors of the theoretical and practical knowledge inherent in the field; musicians capable of contributing to the social transformation and improvement of the quality of life of the people and of the population. (FAMES 2011, 7)

the bachelor’s course of the Music School of UFMG not only focuses on the technical improvement of the musicians but also takes it as a starting point, aiming to capacitate the student—through a broad artistic and humanistic training that takes into account the invaluable number of scientific approaches to the qualified study of music. (UFMG 2011, n.p.)

Thus, the offer of the bachelor’s degree in music … is justified by its potential to continue the development of methodologies for musical refinement and technical preparation of the contemporary world. Thus, it aims to incorporate into the training of students, essential aspects to their formation and to the construction of their citizenship, bearing in mind beliefs, intentions, meanings, interpretations, and assessments that surround the musical experience in our contemporaneity. (UFRJ 2008)

Stemming from what the HEIs studied defined as pertinent to the formation of the bachelor, and considering the 2,400 minimum hours that comprise the curriculum of a bachelor’s course in music in Brazil, what possibilities do the concepts of curriculum offer to the establishment and construction of a wide, critical, and reflective training?

I evoke the principle that the logic of coloniality can be perceived as structured structure which defines ideals, models, and legitimations of what the human must be.

To the dynamics of coloniality underlie a range of tensions, concepts, notions and institutionalized practices…. The intensity of such tensions is high, due to the line traced by coloniality between subject, knowledge and dominant/subordinate ontologies. It is, in turn, permeable and relative. It is frequent that, as individuals who have been colonized through socialization and education, we are converted into recolonizers of our own kind. (Shifres and Rosabal-Coto 2017, 86)

On the other hand, Freire (2015) points out in Pedagogy of the Oppressed—which was developed with and not for people—that the dream of the oppressed who do not become aware of their oppression is to become the oppressor. Inside this perspective, the author notes that

the central problem is this: how can the oppressed, as divided, unauthentic beings, participate in developing the pedagogy of their liberation? Only as they discover themselves to be “hosts” of the oppressor can they contribute to the midwifery of their liberating pedagogy. (Freire 2015, 41)

The path to liberation is not provided. It is discovered and built individually and collectively in the processes of becoming aware. One does not become uncolonized simply because one’s relationship to the colony is no longer historically constructed.

Hence, if we take the curricular grids—disciplines/workload—of the courses analyzed herein, the weight of coloniality becomes evident, not only in terms of an instrumental/vocal European repertoire but also as a concept of auditory perception, methods of analysis, and musical thought. The pedagogical division of the content selected is usually organized into branches. The percentage to be studied in each branch and the condition of mandatory/elective reveal the choice for reproduction or the possibility for renewal within training. This makes me question what a broad, reflective and critical formation might be. Table 4 offers an opportunity for further analysis:

Table 4: Structure and distribution of curricular grids

Table 4: Structure and distribution of curricular grids

Source: Music programs’ curricular documents

Although they belong to the order of complex thought, I dare to use the terms colonial and decolonial to classify their establishment and possibilities within the development of curricular concepts. The term colonial describes maintenance of the reproduction of the Eurocentric ideal. The term decolonial describes the construction of varying, distinct, maybe unforeseen training. I use these terms because I still question what actually is. Is it the amount of theoretical-technical knowledge of a musical practice? Is it the number of hours spent understanding processes but not social contexts in which music is produced? How do criticism and reflection take place in previously locked-down processes which lack options for course paths to those who are being formed?

When observing the data referring to FAMES, I classify their curricular concept as colonial based on reproduction, based on a model to be reached without the possibility of alteration. USP and UFRJ switch between the terms, tilting towards colonial reproduction, since their possible options within training barely even leave the school’s/music department’s curriculum.

The curriculum from UFMG allows, through effective practice of curricular flexibilization, for a possibility of decolonial action/thought. I do not speak in absolute terms, and I don’t even assume that the bachelor’s degree in music from UFMG lies in accordance with decolonial thought. The text and curricular structure, however, allow for heterogeneity, especially in alliance with the expansion of REUNI. Through REUNI, others have gained access to higher education—popular musicians coming from subordinate communities, with different perspectives of musical practice within society. Such facts allow for this inference. I also think that, in addition to the curriculum of a program, the institution’s curricular concept accentuates the possibilities for decolonial actions through the so-called transversal training processes, among which are located the encounters between knowledge and traditional masters.

The Meeting of Knowledges, which takes part in some universities in Brazil and throughout Latin America, is a “political bet” which has been effective to

decolonize the Eurocentric knowledge of the universities with the inclusion of the knowledge of Indigenous, Black and other traditional peoples of the region as part of the repertoire of valid knowledges that should be taught on an equal footing with modern Western knowledge.… The Meeting of Knowledges has a proposal to return the place of the masters and of the clever to the university professors, who are subjected to the capitalist logic of productivism and depersonalization; and, by returning this place, rewrite the dimension of knowledge within the academy, offering conditions to dialogue with the traditional ways while making sure that none is reduced to the exclusive dimension of quantifiable and measurable scientific knowledge. (Carvalho and Flórez-Flórez 2014, 133)

The fact that this policy is present as transversal training in UFMG is not a guarantee of immediate adherence on behalf of the students. It does, however, suggest a possibility within training.

The curriculum in musical (Educ)ação: possibilities and subjects of the practice—a lack of conclusion

I have analyzed, in a theoretical way, the curriculum as a practice, and I have inferred its possibilities for expansion or epistemic reproduction—that is, the maintenance of coloniality or openness to the possibility of a decolonial thought. Therefore, I return to the subjects of the practice. This theoretical thought serves me very little if I withdraw from it the subjects that effectively construct the practice. The openness for reflection of a decolonial nature does not guarantee the fulfillment of the reflection. There needs to be a subject, whether it is a teacher or student, who is aware, who is able to problematize and bring about the discussion, the criticism, and the reflection so as to extend the training process. The curriculum must be put into action. It must be committed to and promote change. After all,

the more I accept who I am and the more I understand the reasons to be and the reasons why I am who I am, the more I am able to change. The more I am able to promote myself, in the case of a naive curiosity to an epistemological curiosity. The assumption that a subject makes of themselves is not possible within a certain way to be without the willingness to change—a process of which they are necessarily a subject of. (Freire 1996, 44)

The curriculum needs a kind of assumption and a change of thought which exceeds the effect of epistemic colonization, which reduces the complexity of knowledge, of expertise, and of unique dimensions—disciplinary, disciplined, and depersonalized dimensions (Carvalho Flórez-Flórez 2014, 133).

That being said, I propose some reflections as to allow an effective decolonial turn to take place in the university.

Even though the curriculum is an official selection of different political-administrative instances of higher education, it also is a practice and is implemented through practice. The role of the university professor is to awaken curiosity within the student regarding possible course paths to be traced in higher education. The role of the student is to become aware of the place they occupy as a subject of education in the higher education system. In the long run “there’s no teacher without a pupil” and vice versa. (Freire 1996, 23)

It may seem like a simple reflection; however, what is the point of a curricular policy that allows for various paths and trainings if its subjects do not put it into practice? How is it possible to transcend the reproducibility of European modernity’s values and practices if this is the only outlook practiced by students and professors? How can one liberate oneself if the individual is not aware?

I go back to the subjects, the graduates of these programs. In questionnaires and interviews regarding the construction of their professional identities, they have reported curricular stiffness, a demotivating factor in training. They have also punctuated:

1. Eurocentric standards, a lack of dialogue with reality, and disciplinarization as breaking from their expectations of their professional training:

I believe that teaching music is still very much geared towards European standards, with its methods, customs, practice, and repertoires. The labor market in Brazil goes far beyond European concert music, and we end up not being ready for this reality. (Tim, bachelor in clarinet, UFRJ)

It lacked dialogue between disciplines and teachers. We at the bachelor’s course were not trained for a realistic market. (Rodman, bachelor in flute, UFMG)

The course is basically structured in the practice of a solo piano repertoire as if you were a soloist. (Fran, bachelor in popular music, UFMG)

I would like the subjects to relate more to one another. (Aurora, bachelor in piano, UFRJ)

2. The freedom of curricular flexibilization as something intimidating:

I found the curriculum very free. This is partially good, but my course ended up lacking a bit of focus. On one hand, freedom in the curriculum is extremely effective because the student can tailor the course according to their needs or professional desires; on the other hand, that very same freedom can be very bad for the graduates who do not have a clear idea of the demands of the professional market, thus making their curriculum deficient in disciplines which are essential for an effective training. (Rita, bachelor in violin, UFMG)

These accounts about the challenges of teaching in higher education are indicated by Masetto (2015), especially with regard to the construction and socialization of interdisciplinary knowledge[15]—the construction of a partnership attitude towards our peers (other professors) and students. The author finds, in the change of the teacher’s posture, the answer to this challenge. It is necessary to have:

[a] mediator teacher who learns to work as a team with students and with their peers in the construction of process of teaching a UNIVERSITY LECTURE, understood as the space-time in which CHARACTERS act and interact; and in this intercourse of actions, they BUILD a process of learning and CITIZEN PROFESSIONAL TRAINING. (Masetto 2015, the author’s emphasis)

Taking into consideration the proposal of a broad, critical, and reflective training, and understanding the university lecture as any space-time in which experiences become conscious learning directed toward citizen professional training, the curriculum as a practice may be perceived as locus for social prophylaxis.

Social prophylaxis is a preventive action for the common/individual good. It is a metaphor that originated in the health sciences, as a set of measures aiming to preserve and maintain health, as a means to avoid hazards. Prophylaxis, when put into action in society, finds its space in education as a field of information and (trans)formation of the human being. Here, I contemplate the possibility of educational systems which develop a broad training that transcends content and techniques, and may reflect more humane values, doomed to uncompleted beings (Freire 1996).

Finding possibilities of prophylactic action in higher music education and in its formats of curricula requires an understanding of music education as “social prophylaxis” (Caznok 2013). This thought regards music education in its hybrid state: education as a political project and music as a relationship. It conceives a musical education that takes into account alterity and what is different, through the equity of the processes of transmission of knowledge, the processes of training, and insertion of professional musicians in the market.

Education, as a dialectical movement in/for human development … requires us to think beyond the harsh realities which are sometimes imposed in schools and naturalized by those who do not believe in education as a force to generate social and cultural transformations, a force able to promote change. (Nörberg and Foster 2016, 190)

I suggest such prophylaxis through higher education training because I believe that well-trained professionals can break down or reinvent cycles which have become vicious in the labor market, in the school system, and in the notion of being/perceiving oneself in the world. Curricular flexibilization, change in the posture of professors and students, and the transit among knowledge highlight the possibilities for turns of thought that break the silencing of colonial history.

About the Author

A native of Brazil, Euridiana Silva Souza holds a PhD in Music Education, a Master’s in Study of Musical Practices, and a Bachelor’s in Piano from Universidade Federal de Minas de Gerais. She has undertaken research on the formation of professional identities of musicians and processes of formation in higher music education. She has taught courses in the Licentiate of Music (Teacher Training) at Universidade de Brasília and was pianist and teacher at Orquestra de Câmara do Sesi. She currently coordinates music courses at Fábrica de Artes in Belo Horizonte city, and is pianist with the chamber ensembles DuoAlismo (viola and piano) and TripTango (oboe, viola, and piano).

References

Anacoana, Paula 2012. Eu sou favela – coletivo [I am slum – collective]. Anacoana Editions.

Antunes, Vinícius Volcof. 2016. Expansão e democratização universitária: A implementação do REUNI na Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro [University expansion and democratization: The implementation of REUNI at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro]. Revista Habitus 14 (1): 91–9.

Aredes, Rubens. 2015. A bimusicalidade na relação entre universidade e favela. Reflexões sobre uma experiência etnomusicológica em uma favela brasileira [The bi musicality in the relationship between university and slum. Theoretical reflections on ethnomusicological experience in a Brazilian slum]. Post-ip ?15 Post-in-progress: Revista do Fórum Internacional de Etudos em Música e Dança 3: 239–46.

Arroyo, Margarete, Elizabeth Lucas, Marilia Stein, and Luciana Prass. 2003. Entre congadeiros e sambistas: Etnopedagogias musicais em contextos populares de tradição afro-brasileira [Among congadeiros and samba musicians. Ethnopedagogies in popular contexts of Afro-Brazilean tradition]. Revista da Fundarte 3 (5): 4–20.

Ballestrin, Luciana. 2013. América Latina e o giro decolonial [Latin America and the decolonial turn]. Revista Brasileira de Ciência Política 11: 89–117.

Bennett, Dawn E. 2008. Understanding the classical music profession. London: Routledge.

Borges, Maria, and Orlando Aquino. 2012. Educação superior no Brasil e as políticas de expansão de vagas do REUNI: Avanços e controvérsias [Higher education in Brazil and the policies for increasing the number of vacancies from REUNI: Advances and controversies]. Educação: Teoria e Prática 22 (39): 117–38.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 2008. A distinção: Crítica social do julgamento [Distinction: A social critique of the judement of taste]. São Paulo: Edusp.

Catani, Afrânio, João de Oliveira, and Luiz Dourado. 2001. Política educacional, mudanças no mundo do trabalho e reforma curricular dos cursos de graduação no Brasil [Educational policy, changes in the labor world, and curricular reform of degree courses in Brazil]. Educação & Sociedade 22 (75): 67–83.

Carvalho, José Jorge, and Juliana Flórez-Flórez. 2014. Encuentro de saberes: Proyecto para decolonizar el conocimiento universitario eurocentrico [Encounter of knowledges: Project to decolonize Eurocentric university knowledge]. Nómadas 41: 131–47.

Caznok, Yara. 2013. A educação musical como profilaxia social [Music education as social prophylaxis]. Montevideo: FLADEM.

CNE—Conselho Nacional de Educação / Ministério da Educação. 2004. Resolução nº2 [Resolution No. 2]. Brasília: MEC. Accessed from: portal.mec.gov.br/cne/arquivos/pdf/p04.pdf.

Coelho, Maria de Lourdes. 2014. O programa REUNI na UFMG: Contexto, adesão, implantação, criação do Giz e suas ações formativas [REUNI program at UFMG: Context, adherence, implantation, creation of Giz and its formative actions]. Revista Docência do Ensino Superior 4: 3–46.

Dempsey, Genevieve. 2017. The acoustics of justice: Music and myth in Afro-Brazilian congado. Yale Journal of Music & Religion 3 (2): 1–25.

Elliot, David. 1995. Music matters: A new philosophy of music education. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Faculdade de Música do Espírito Santo—FAMES. 2011. Projeto pedagógico do curso de bacharelado em música [Pedagogical project of the bachelor’s degree in music]. Vitória.

Ferreira, António Gomes. 2008. O sentido da educação comparada: Uma compreensão sobre a construção de uma identidade [The meaning of comparative education: An understanding of the construction of an identity]. Educação 31 (2): 124–38.

Fragoso, Daisy. 2018. Interlocuções entre a etnomusicologia e a educação musical [Interlocutions between ethnomusicology and music education]. Revista Música 18 (1): 143–69.

Freire, Paulo. 2015. Pedagogia do oprimido [Pedagogy of the opressed]. 51st ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra.

Freire, Paulo. 1996. Pedagogia da autonomia: Saberes necessários à prática educativa [Pedagogy of autonomy: Necessary knowledge for educational practice]. 23rd ed. São Paulo: Paz e Terra.

Garcia, Walter. 2013. Rap. In Dimensões políticas da justiça, edited by Leonardo Avritizer, Newton Bignotto, Fernando Filgueiras, Juarez Guimarães, and Heloísa Starling, 637-646/ Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira.

Green, Lucy. 2014. Music education as critical theory and practice—Selected essays. Surrey: Ashgate.

Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2013. Desenvolvimentismo, modernidade e teoria da dependência na América Latina [Developmentalism, modernity, and theory of dependence in Latin America]. Realis 3 (2): 26–55.

Hair Jr., Joseph, William Black, Barry Babbin, Rolph Anderson, and Ronald Tatham. 2009. Análise multivariada de dados [Multivariance data analysis]. Porto Alegre: Bookman.

Herscovici, Alain. 2005. Historicidade, entropia e não linearidade: Algumas aplicações possíveis na ciência econômica [Historicity, enthropy, and linearity Possible applications in economics science]. Revista de Economia Política 25 (3): 277–94.

Heusi, Alina Cristina da Silva. 2014. Determinação do cálculo de custo por vaga e matrícula efetiva em universidade pública: Um estudo de caso no Centro de Artes da Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina [Calculation of cost per student vacancy and effective enrollment in public universities: A case study at the Arts Center of the State University of Santa Catarina]. Master’s thesis. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Administração, CCAS. Florianópolis: UDES.

Kummu, Matti, and Olli Varis. 2011. The world by latitudes: A global analysis of human population, development level and environment across the North–South axis over the past half century. Applied Geography 31 (2): 495–507.

Lander, Edgardo, ed. 2005. A colonialidade do saber: Eurocentrismo e ciências sociais. Perspectivas latinoamericanas [Coloniality of knowledge: Eurocentrism and social sciences]. Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

Léda, Denise, and Deise Mancebo. 2009. REUNI: heteronomia e precarização da universidade e do trabalho docente [REUNI: heteronomy and precariousness of university and teachers’ work]. Educação e Realidade 34 (1): 49–64.

Leite, Lúcia Helena Alvarez. 2010. Com um pé na aldeia e um pé no mundo: Avaços, dificuldades e desafios na construção das escolas indígenas públicas e diferenciadas no Brasil [One foot on the village and another in the world: Advances, difficulties, and challenges in the construction of public Indigenous and differentiated schools in Brazil]. Currículo sem fronteiras 10(1): 195–212.

Lima, Edileusa Esteves, and Lucília Regina de Souza Machado. 2016. REUNI e Expansão Universitária na UFMG de 2008 a 2012 [REUNI and University Expansion at UFMG from 2008 to 2012]. Educação & Realidade 41 (2): 383–406.

Lopes, Alice Casimiro, and Silvia Braña Lopéz. 2010. A performatividade nas políticas de currículo: O caso do Enem [Performativity in curricular policy: the case of Enem]. Educação em Revista 26 (1): 89–110.

Louro, Ana Lúcia, and Jusamara Souza. 1999. Reformas curriculares dos cursos superiores em música e formação de professores de instrumento [Curricular reforms of higher music courses and music instrument teacher training]. XII Encontro da ANPPOM, Salvador. Retrieved from https://antigo.anppom.com.br/anais/anaiscongresso_anppom_1999/ANPPOM%2099/PAINEIS/LOURO.PDF

Louro, Ana Lúcia. 1998. Formação do professor de instrumento: Grades curriculares dos cursos de bacharelado Fundamentos da Educação Musical [Music instrument teacher training: Syllabus of bachelor’s courses ‘Foundations of Music Education’]. Revista da ABEM 4: 106–9.

Louro, Ana Lúcia. 1997. Disciplinas pedagógicas no curso de bacharelado em Música [Pedagogical disciplines in the degree course in Music]. Expressão 1 (1–2): 17–20.

Lucas, Glaura. 2002. Musical rituals of Afro-Brazilian religious groups within the ceremonies of congado. Yearbook for Traditional Music 34: 115–27.

Luedy, Eduardo. 2009. Analfabetos musicais, processos seletivos e a legitimação do conhecimento em música: Pressupostos e implicações pedagógicas em duas instâncias discursivas da área de música [Musical illiterates, selective processes, and the legitimation of knowledge in music: Assumptions and pedagogical implications in two discursive instances in the area of music]. Revista da ABEM 22: 49–55.

Masetto, Marco Tarciso. 2015. Desafios para a docência no ensino superior na contemporaneidade [Challenges for teaching in higher education in contemporary times]. In Didática e prática de ensino: Diálogos sobre a escola e formação de professores e a sociedade. 1st ed., edited by M. M. D. Cavalcante, J. A. J. Sales, I. M. S. Farias, and M. S. L Lima, 779–95/ Fortaleza: EdUECE.

Merriam, Alan P. 1964. The anthropology of music. Illinois: Northwestern University Press.

Miglievich-Ribeiro, Adelia. 2014. Por uma razão decolonial: Desafíos ético-político-epistemológicos à cosmovisão moderna [For a decolonial reason: Ethical-political-epistmological challenges to the modern worldview]. Civitas-Revista de Ciências Sociais 14(1): 66–80

Mignolo, Walter D. 2003. Histórias globais, projetos locais: Colonialidade, saberes subalternos e pensamento liminar [Global histories, local projects: Coloniality, subaltern knowledges, and liminal thought]. Belo Horizonte: Ed. UFMG.

Moraes, Mariana Ramos de. 2018. De religião a cultura, de cultura a religião: Travessias afro-religiosas no espaço público [From religion to culture, from culture to religion: Afro-religious journeys in public space]. Belo Horizonte: PUC Minas.

Nettl, Bruno. 2010. Music education and ethonomusicology: A (usually) harmonious relationship. Paper presented at the 29th World Conference of International Society for Music Education, Beijing, China.

Nörberg, Nara Eunice, and Mari Margarete dos Santos Forster. 2016. Ensino superior: As competências docentes para ensinar no mundo contemporâneo [Higher education: Teacher competencies to teach in the contemporary world]. Revista de Docência do Ensino Superior 6 (1): 187–210.

Palombini, Carlos. 2013. Funk proibido [Forbidden funk]. In Dimensões políticas da justiça, edited by Leonardo Avritizer, Newton Bignotto, Fernando Filgueiras, Juarez Guimarães, and Heloísa Starling, 647–56/ Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira.

Pereira, Marcus Vinícius Medeiros. 2013. O ensino superior e as licenciaturas em música: Um retrato do habitus conservatorial nos documentos curriculares [Higher education and teacher training degrees in music: A portrait of conservatorial habitus in curricular documents]. Campo Grande: Ed. UFMS.

Porto-Gonçalves, Carlos Walter. 2005. Apresentação da edição em português [Preface to the Portuguese edition]. In A colonialidade do saber: eurocentrismo e ciências sociais. Perspectivas latinoamericanas, edited by Edgardo Lander, 3-5/ Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

Quijano, Aníbal. 2005. Colonialidade do poder, eurocentrismo e América Latina [Coloniality of power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America]. In A colonialidade do saber: Eurocentrismo e ciências sociais. Perspectivas latinoamericanas, edited by Edgardo Lander, 107–30/ Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

Reinert, Clio. 2005. Metodologia para apuração de custos nas IFES brasileiras [Methodology for cost research in Brazilian IFES]. Master’s thesis. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Administração. Florianópolis: Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina.

Sacristán, José Gimeno. 2000. O currículo: Uma reflexão sobre a prática [Curriculum: A reflection on practice]. 3rd ed. Porto Alegre: ArtMed.

Sánchez Vásquez, Adolfo. 2011. Filosofia da práxis [Philosophy of praxis]. 2nd ed. São Paulo: Expressão Popular.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. 2007. Para além do pensamento abissal – das linhas globais a uma ecologia de saberes [Beyond abyssal thinking – From global lines to ecology of knowledges]. Novos Estudos 79: 71–94.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. A universidade no século XXI [University in the 21st century]. São Paulo: Cortez Editora.

Shifres, Favio, and Daniel H. Gonnet. 2015. Problematizando la herencia colonial en la educación musical [Problematizing the colonial legacy in music education]. Epistemus 3 (2): 51–67.

Shifres, Favio, and Guillermo Rosabal-Coto. 2017. Hacia una educación musical decolonial en y desde América Latina [Towards a decolonial music education in and from Latin America]. RIEM 5: 85–90.

Tugny, Rosângela Pereira de. 2015. Agência dos objetos sonoros [Agency of sonorous objects]. Per Musi 31: 322–44.

Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais – UFMG. 2011. Projeto pedagógico [Pedagogical project]. Belo Horizonte.

Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro – UFRJ. 2008. Curso de bacharelado em música—projeto pedagógico [Bachelor’s degree program in music—pedagogical project]. Rio de Janeiro.

Universidade de São Paulo – USP. 2017. Bacharelado em música [Bachelor’s degree program in music]. São Paulo.

Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. 2014. A inconstância da alma selvagem [Inconstancy of the wild soul]. Brazil: Cosac Naify.

Woodford, Paul. G. 2002. The social construction of music teacher identity in undergraduate music education majors. In The new handbook of research on music teaching and learning, edited by Richard Colwell and Carol Richardson, 675–94/ New York: Oxford University Press.

Yúdice, George. (2013). A conveniência da cultura: Usos da cultura na era global [The convenience of culture: Uses of culture in the global era]. Belo Horizonte: Ed. UFMG.

Notes

[1] In the Portuguese version of this article, capital letters emphasize the meaning of action (ação) present in the word (educ)ação. The meaning conveyed in Portuguese has no direct equivalent in English; hence, in this English translation, I utilize the neologism (educ)ACTION.

[2] The parentheses game with the word education makes sense in Portuguese – Educação, since “ação” denotes practice. In English, such a game does not make immediate sense because it changes the writing of the word: educ + action = (educ)ation.

[3] When you assign adjectives to and find a conservatorial habitus in the curricular documents of teacher training in music, Pereira (2013) suggests what is not necessarily a complaint, a demonization of the conservatorial system itself. He suggests an awareness of the fact that many curricular changes were made in a cosmetic fashion. The awareness of this habitus is a step towards its process of transformation, so as not to perceive this Eurocentric concept as the only destination, but as a possibility within several that exist in our musical practice. On the impacts of the conservatorial model as a colonial heritage, see Shifres and Gonnet (2015).

[4] The parentheses in (de)colonial suggest the possibility of both. I am making this writing choice so as to avoid the repetition of the terms colonial/decolonial too frequently.

[5] The analysis of the Brazilian demographic and economic census may be found directly on the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics’ website: https://ww2.ibge.gov.br/home/default.php.

[6] The higher courses in music are offered in the modalities of bachelor’s degree (instruments/performance) or teacher training in music (with qualification in instruments or music education). It is important to emphasize the difference within the terms applied in higher education throughout the remainder of Latin America. The courses equivalent to Brazil’s bachelor’s degree are called teacher training. The courses equivalent to Brazil’s teacher training are called pedagogies.

[7] In Brazil, there are about 275 indigenous ethnicities, according to FUNAI (National Indigenous Foundation). The nation census conducted by IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics) showed a total of 817.963 indigenous people in the country, of whom 97.960 are located in the Southeast (IBGE 2010). Over the last decade, it has been possible to see further insertion of the indigenous cultures in the academic spaces: as students in indigenous educators training programs, different regular courses or as masters of traditional knowledge. The communication barriers of linguistic and cultural differences become more flexible inside this space because of the decolonial thought. See Carvalho and Flórez-Flórez (2014); Leite (2010).

[8] The Quilombos, historically, were strongholds of shelter and resistance during slavery in Brazil. Many communities were constituted in these strongholds, perpetuating and resignifying their traditions of African matrices, especially those of the popular Catholicism. In 1988, with the process of redemocratization of Brazil, these communities started to have some visibility within politics. They have been since fighting for their rights. The Normative Instruction n. 16, enacted by the Federal Government in 2004, states that: “ethnic-rational groups, according to self-evaluation, which possess their own historical path, specific territorial relations and presumption of African descent, linked to resistance to the historical oppression, are considered as remainders of the Quilombo communities. Considered land of the remainder of the Quilombo communities is all the land used as guarantee of their physical, social, economic and cultural reproduction, as well as the areas containing environmental resources necessary for the preservation of their habits, traditions, culture and leisure, comprising households, spaces destined to religious cults and places which hold historic reminiscences of the old Quilombos.

[9] The course’s peculiarity is highlighted by individual lectures on instruments/singing. This particularity rises the values of “cost per vacancy” and “cost per student” or “cost per effective vacancy.” The discussion over these values, which is done in the sphere of the administration of the university and of public administration, demands the comprehension of costing systems and division of funding. According to Heusi (2014), these processes are nor homogenous or defined under the same framework. The varying calculations of the “cost per student” integrate: available resources, total cost of the university level activities (graduation and post-graduation courses (strictu sensu), cost of the administration and teacher training, cost of end-activities (teaching, research and extension), average cost of the teaching hour, cost of unfilled vacancies and temporary retentions in training, etc (Reinert 2005).

[10] Although the total number of HEI offering bachelor’s courses is 52, only 51 are indicated in the map (figure 1), since one of the institutions offers a distance education course (EaD), thus making its physical location indifferent.

[11] The methodological decision of working with the data available on the websites is justified because it is data accessible for every student, candidate or egress. Even though the websites may be modified, the collection of data regarding these documents was carried out systematically, monitoring every content update.

[12] In order to understand the unified exam—ENEM (National Exam of High School Education), see Lopes and Lopes (2010). Regarding reflections on the specific skills exam (SSE) entry application to higher education in music, see Luedy (2009).

[13] Analysis of the implementation of REUNI in UFMG may be consulted in Lima and Machado (2012); Coelho (2014). On the illusion of democratization and implementation of REUNI in UFRJ, see Antunes (2016). On the relations of the implementation of REUNI and instability of teaching jobs in higher education, see Léda and Mancebo (2009). On the advances and controversies regarding REUNI, see Borges and Aquino (2001). To see MEC’s official reports on REUNI, see http://reuni.mec.gov.br.

[14] “Culture-as-resource is much more than commodity; it is the lynchpin of a new epistemic framework in which ideology and much of what Foucault called disciplinary society (i.e.; the inculcation of norms in such institutions as education, medicine, and psychiatry) are absorbed into an economic or ecological rationality, such the management, conservation, access, distribution, and investment—in ‘culture’ and the outcomes thereof—take priority”(Yúdice 2013, 13).

[15] A transdisciplinarity or an interdisciplinarity perhaps, as Viveiros de Castro (2002) suggests.