A Social-Cognitive Theoretical Framework for Examining Music Teacher Identity

EDWARD McCLELLAN

Loyola University, Louisiana, USA

October 2017

Published in Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 16 (2): 65–101. [pdf]

doi:10.22176/act16.2.65

The purpose of the study was to examine a diverse range of research literature to provide a social-cognitive theoretical framework as a foundation for definition of identity construction in the music teacher education program. The review of literature may reveal a theoretical framework based around tenets of commonly studied constructs in the social-cognitive theory, social identity theory, symbolic interactionism, and role theory to ground future research on music teacher constructs which may be examined through both quantitative and qualitative measures. The proposed theoretical framework within this study might further the ways through which the profession investigates music teacher identity construction, and enhances university teacher training and induction, enriching the lives of future music educators.

Keywords: Social-cognitive theory, music teacher identity, identity construction, social identity theory, symbolic interactionism, role theory

The construction of music teacher identity in undergraduate music education majors is an extremely complicated topic requiring examination of several related literatures including sociology, teacher education, psychology, social psychology, and music education (Woodford 2002, 675). Music teacher identity is examined in the literature, but common terminology remains undefined. For example, sociologists use the phrase ‘constructing identity’ while psychologists use the term ‘developing identity’ (Wagoner 2014, 2). Identity construction implies that one plays an active role in determining how identity is formed, while identity development implies a predetermined process.

Despite the increasing prevalence of social construction models in music teacher education, undergraduates appear to be not so much constructing an identity for themselves as replicating past practices, including traditional notions of music teacher identity (Beynon 1998; Harwood 1993; L’Roy 1983; Prescesky 1997; Roberts 1991a, 1991c, 1991d, 1993, 2000b). In order to further the ways through which the profession investigates music teacher identity construction, enhances university teacher training and induction, and enriches the lives of future music educators, it is necessary to identify a theoretical framework in social-cognitive theory as a foundation for definition of identity construction in the School of Music (i.e., music teacher education program). This social-cognitive theoretical framework may serve to ground future research on music teacher identity through constructs which may be examined through both quantitative and qualitative measures.

The Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine constructs consistent across all occupational identity research areas to create a social-cognitive theoretical framework that may further the ways through which the profession investigates music teacher identity construction in the music teacher education program. The guiding research questions were as follows:

- What tenets of commonly studied theoretical constructs in sociology, psychology, social psychology, education, and music teacher education are related to music teacher identity construction in the undergraduate music education program?

- What social-cognitive constructs, models, and/or frameworks currently exist that define music teacher identity construction of pre-service music teachers?

- What theoretical framework would best initiate understanding of the complex process of music teacher identity construction wherein all constructs are integrated, and elements and circumstances can be observed and evaluated?

Method

Research literature on social identity theory, symbolic interactionism, role theory, and occupational identity that affect undergraduate music education major identity orientation was reviewed to examine conceptual elements, theories, and design attributes that contribute to identity construction in pre-service music teachers. Consideration was given to tenets of commonly studied constructs in which social origins of thinking, behavior, and environment are integrated with the collective impact of people and experiences in given contexts. The investigator examined individual theoretical models and model design characteristics, as reflected through the literature, to propose a social-cognitive theoretical framework which advances the ways through which the profession investigates music teacher identity construction and enriches university music teacher training and induction.

Overview of the Literature Review

A breadth of research literature has been examined in this study to provide a social-cognitive theoretical framework as a foundation for definition of identity construction in the music teacher education program. This investigation of relevant research sources opens with descriptions and working definitions of the construct identity, social-cognitive theory and role-identity theory, and the process of identity formation to set context for the social-cognitive framework proposed later in this paper.

The “Identity Formation” section, in particular, presents origins of Erickson’s Developmental Stage Theory, Marcia’s Identity Status Theory, Berzonsky’s Identity Formation Model and Identity Style Inventory in order to distinguish essential elements of identity formation and the social-cognitive processes and strategies adolescents engage in constructing, maintaining, and/or reconstructing a sense of identity in daily life.

In “Music Teacher Identity Construction,” an overview of research linking social theories of identity to the examination of music teacher identity construction, examination of the theoretical constructs of social interactions, socialization, and symbolic interactionism as applied to occupational socialization and development of occupational identity as a pre-service music teacher, and the influences of the university school of music culture on music education major socialization and resultant identity construction are presented to the reader. Throughout this section, attention is given to tenets of social theory, socialization, symbolic interactionism, role theory, and occupational identity through which the profession has examined music teacher identity construction. These research sources are presented to provide some context of recent investigation of music major identity construction in the university music teacher education program.

“Implications of Specific Theoretical Frameworks” presents common salient elements from the definitions, designs, theoretical frameworks, and model design characteristics and attributes of music teacher identity construction found in the research. Of the many studies on this subject, several researchers have attempted to design models (Bouij 1998, Brewer 2009) or define constructs or model design characteristics and attributes (Hargreaves 2007, McClellan 2014, Wagoner 2014) of pre-service music teacher identity. Other researchers have defined measurable behaviors related to the development of occupational role identity as a music teacher (Carper and Becker 1970, Hargreaves et al. 2007, Teachout and McKoy 2009).

“A Theoretical Framework of Identity Construction” extracts the findings from research studies and insights from theories from which the profession has studied music teacher identity construction. The distinct attributes of Bouij’s (1998) theoretical Model of Socialization and Salient Role Identities and Brewer’s (2009) Conceptions of Effective Teaching and Role-Identity Development, with research supporting a theoretical framework centering on the integration of musician and teacher identities, salient characteristics of effective teaching (e.g., teaching skills, musical skills, personality skills), and definitions of music teacher identity founded on the examination of theoretical and research literature based around tenets of social identity theory, symbolic interactionism, and role theory have been synthesized to propose a social-cognitive theoretical framework through which the profession may investigate and enhance music teacher identity construction.

Findings

Identity, the construct

Identity is a powerful construct. It guides life paths and decisions (Kroger 2007), and allows people to draw strength from their affiliations with groups and collectives (Brewer and Hewstone 2004, Schildkraut 2007). The term identity is sometimes applied as a catch-all label for biological characteristics, psychological dispositions, and/or socio-demographic positions (Vignoles, Schwartz, and Luyckx 2011, 2). Existing approaches to identity typically focus on one or more of three different “levels” at which identity may be defined: individual, relational, and collective (Sedikides and Brewer 2001; Vignoles, Schwartz, and Luyckx 2011, 3).

Identity is one of the most commonly studied constructs in the social sciences (Brubaker and Cooper 2000, Côté 2006). A working definition of identity may be rather broad, extending way beyond the individual self to encompass significant others, social roles, face-to-face groups, and wider social categories (Vignoles, Schwartz, and Luyckx 2011, 4). Identities are both personal and social (Vignoles, Schwartz, and Luyckx 2011, 5). Clearly, many identity processes are undertaken deliberately and may involve a great deal of conscious effort on the part of individuals and groups. Many processes of personal identity formation, such as exploring potential goals, values, and beliefs and committing oneself to one or more of the options considered, are typically conceptualized as conscious, purposeful, and reasoned choices made by individuals (Berzonsky 1990, Kroger and Marcia 2011, Luyckx et al. 2006).

Social-Cognitive Theory

Social-Cognitive Theory is an approach to understanding human cognition, motivation and emotion, which assumes that people are active agents in shaping their environments (Bandura 1986, 1997; Maddux 1993; Maddux and Gosselin 2003; Strachan 2005, 4). Identity is conceptualized as a cognitive structure or self-theory, which provides a personal frame of reference for interpreting self-relevant information, solving problems, and making decisions (Berzonski 2011). Social Cognitive Theory provides a means of measuring social cognitions that may be important in behavioral regulation relative to identity.

Identity is viewed as a process that governs and regulates the social-cognitive strategies used to construct, maintain, and/or reconstruct a sense of personal identity (Berzonski 2011). Social Cognitive theory assumes that people are able to symbolize their experiences into internal models of action that allow them to engage in forethought to purposefully direct their behavior (Strachan 2005). Cognitive processes are implicated in the construction, maintenance, and change of identities.

Social cognition and symbolic interaction, two of the prevailing perspectives in sociological social psychology, provide the theoretical underpinnings of traditional understandings of identity. The basic premise of symbolic interaction is that people attach symbolic meaning to objects, behaviors, themselves, and other people, and they develop and transmit these meanings through interaction. Interactionist approaches to identity vary in their emphasis on the structure of identity, and the processes and interactions through which identities are constructed. The more structural approach relies on the concept of role identities, the characters a person develops as an occupant of particular social positions, explicitly linking social structures to persons (Stryker 1980).

McCall and Simmons (1978) describe role-identity as “the character and the role that an individual devises for himself as an occupant of a particular social position” (65). A person has multiple role-identities that may change over time and in differing situations. Stets (2006) contends that people derive meanings about a particular role-identity from two sources: their own personal understanding of the role and the cultural and social structure in which they have been socialized. Individuals employ both of these sets of meanings as they enact a role-identity. When enacting that role-identity, others are always claiming an alternative role-identity in the interaction (Draves 2014, 199).

Identity Formation

Identity formation is an essential developmental challenge associated with adolescence (Côté 2009; Erikson 1950, 1964, 1968). According to Erikson (1950), the particular stage relevant to identity formation takes place during adolescence (ages 12–20). This Identity vs. Role Confusion stage consists of adolescents trying to figure out who they are in order to form a basic identity that they will build on throughout their life. During the identity stage, the salient issues are occupation and ideology as individuals decide how to make their way in the world and what to believe in (Vaziria, Kashania, Jamshidifara, and Vazirib 2014, 316).

Marcia (1966) developed a framework for studying Erikson’s concept of identity using crisis and commitment as organizing principles (Vaziria, Kashania, Jamshidifara, and Vazirib 2014, 316–17). Marcia (1980) introduced four identity statuses as Identity Achievement (committed individuals who have personally experienced and resolved a crisis period of self-examination); Moratorium (uncommitted individuals currently negotiating a personal crisis); Foreclosure (committed persons who have not had a personal crisis tend more automatically to identify with the expectations held for them by others, especially their parents); and Identity Diffusion (uncommitted persons who are not currently exploring identity issues) (Berzonsky 1989, 268). Marcia (1980) concluded that adolescents in both the achieved (high commitment and exploration) and foreclosed (high commitment and low exploration) statuses scored higher on self-esteem than adolescents in the moratorium (low commitment and high exploration) and diffusion (low commitment and exploration) statuses (Soenens, Berzonsky, and Papini 2015, 1).

In the 1980s, researchers began to focus on the process by which identity is formed (e.g., Berzonsky 1986, 1988; Grotevant 1987; Marcia 1988) rather than individual differences in identity outcomes (Berzonsky 1989, 269). According to this view, identity is conceptualized as a structure as well as a process. Identity as a cognitive structure serves as a personal frame of reference for interpreting experience and self-relevant information and answering questions about the meaning, significance, and purpose of life. As a process, identity directs and governs the resources adolescents use to cope and adapt in everyday life (Berzonsky 1990; 2004, 304). Appropriately, identity development is considered to involve an ongoing dialectical interchange between assimilative processes governed by the identity structure and accommodative processes directed by the social and physical contexts within which adolescents live and develop (Berzonsky 1990, 1993). The model also postulates differences in how adolescents deal with or manage to avoid the tasks of maintaining and revising their sense of identity (Berzonsky 1988, 1993).

Berzonsky (1990) proposed a process model of identity formation that focused on differences in the social-cognitive processes and strategies individuals use to engage or avoid the tasks of constructing, maintaining, and/or reconstructing a sense of identity (Vaziria, Kashania, Jamshidifara, and Vazirib 2014, 320). Berzonsky’s (1988) suggested that the four outcomes classified by Marcia’s (1966) status paradigm may reflect or be associated with differences in the process by which personal decisions are made and problems are solved (Berzonsky 1989, 269).

Berzonsky (1989, 1990) differentiated three social-cognitive processing orientations or identity styles individuals use to make decisions, deal with personal problems, and govern and regulate their lives. Individuals with an Informational identity processing style are self-reflective, skeptical about self-views, open to new information, and willing to examine and revise aspects of their identity when faced with dissonant feedback (Berzonsky 1990). Normative processing style individuals more automatically adopt a collective sense of identity by internalizing the standards and prescriptions of significant others and referent groups. Those with a diffused-avoidant processing style are reluctant to confront and face up to identity conflicts, and avoid making decisions; they procrastinate and delay as long as possible. Identity processing styles are differentially associated with the type of self-relevant information or self-elements individuals utilize to form their sense of identity (Cheek 1989).

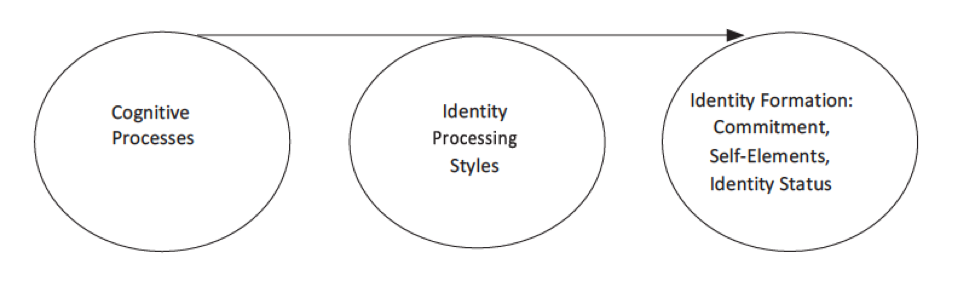

Berzonsky’s (2010) model postulates that while both general cognitive processes and identity processing styles directly account for variation in identity processes, associations between general cognitive processes and various markers of identity formation will at least in part be mediated by identity processing styles (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Model of hypothesized relationship between cognitive processes, identity style, and identity formation (adapted from Berzonsky 2008)

The Identity Style Inventory (Berzonsky 1990) or translated versions have been used in more than 15 different cultural contexts or countries including Poland (Senejko 2007), India (Srivastava 1993), the Czech Republic (Macek and Osecká 1996), Slovakia (Sramova and Fichnova 2008), Finland (Numri, Berzonsky, Tammi, and Kinney 1997), Greece (Vleioras and Bosma 2005), Hungary (Sallay 2002), Canada (Adams, Berzonsky, and Keating 2006), South Africa (Seabl 2009), Italy (Crocetti, Rubini, Berzonsky, and Meeus 2009), Germany (Krettenauer 2005), the Netherlands (Berzonsky, Branje, and Meeus 2007), Denmark (Jorgensen 2009), Spain (Munoz Garcia 1998), Turkey (Celen and Kusdil 2009), Australia (Caputi and Oades 2001), Belgium (Duriez, Soenens, and Beyers 2004), China (Xu 2009), and Iran (Hejazi, Shahraray, Farsinejad, and Asgary 2009).

According to Berzonsky’s (2004) social-cognitive model, individuals differ in how they approach or avoid the tasks of constructing and reconstructing a sense of identity and those differences play a role in how effectively they deal with various identity functions like coping with personal problems, resolving conflicts and stressors, maintaining a coherent sense of self, establishing social relations, and successfully governing and regulating their lives. Generally, use of both informational and normative styles is positively associated with firm goals, commitments, a sense of direction and purpose, and relatively effective behaviour (Adams et al. 2002; Berzonsky 1998, 2003; Berzonsky and Kuk 2000; Dollinger 1995). However, the more adolescents are expected to assume personal responsibility for setting their own priorities and monitoring their own behaviour, especially in diverse and changing environmental contexts, the less adaptive a normative orientation may become (Berzonsky and Kuk 2000).

Music Teacher Identity Construction

Undergraduate music education major identity formation is a primary factor in pre-service music teacher education. Research linking social theories of identity and music has included examination of music teacher identity construction (Colwell and Richardson 2002), applications of interactionism to teaching music (Froehlich 2007), consideration of connections between the sociology of education and music education (Paul and Ballantine 2002), and musical self-socialization (Mueller 2002). Music education researchers continue to examine the identity development of future music educators (e.g., Austin, Isbell, and Russell 2012; Austin and Miksza 2009; Berg 2010; Haston and Russell 2012; Hourigan and Thornton 2009; Isbell 2008; McClellan 2014; Russell 2012).

Austin et al. (2012) defined socialization as “the collective impact of people and experiences most connected to the individual or context,” and claimed occupational identity is “a merger of teacher-musician and self-other dimensions” based on symbolic interactionism (Blumer 1969). Froehlich (2007) emphasizes that individuals are socialized by their choice of membership in cultures, their efforts to become familiar with the chosen cultural codes, values, and subculture practices, and by shaping these cultures and contributing to their cultural production. They identify with these groups, and these associations become part of their identity construction process (Mueller 2002). Froehlich and L’Roy (1985) confirm an important theoretical construct of social interactions as applied to occupational socialization according to which people perceive themselves and act the way they think others perceive them and want them to act (70).

Researchers (Brewer 2009, L’Roy 1983, McClellan 2014) found that the development of occupational identity results from interactions with others, professors, peers, supervisors, cooperating teachers, and the training environment. Music education professors and field experiences offered as curricular components of music education programs were also revealed as key to music education majors’ socialization (Austin et al. 2012, Conkling 2003, Isbell 2008, McClellan 2014). Evans and McPherson (2015) also contend that the formation of long-term identity is influenced by school culture and social environment. Therefore, the college or school of music is a primary setting of secondary socialization for undergraduate music education majors pursuing music education as a profession and therefore identity construction (Austin et al. 2012, McClellan 2014).

Implications of Specific Theoretical Frameworks

Symbolic interactionism has been the most pervasive model in music education research to investigate socialization and occupational identity among pre-service music teachers (Isbell 2008; L’Roy 1983; Paul 1998; Roberts 2000a, 2000c; Paul 1998; Wolfgang 1990). L’Roy’s (1983) study, described as symbolic interactionist, examined the development of occupational identity of undergraduate music education majors in a particular institutional culture, and addressed many of the same problems as Roberts (1991a, 1991c, 1991d). Roberts’ (1991a, 1991c, 1991d) ethnographic study of the construction of professional identity in undergraduate music education majors is highly original in that it was the first attempt to make explicit undergraduate music education majors’ perceptions of their everyday social reality in their own words.

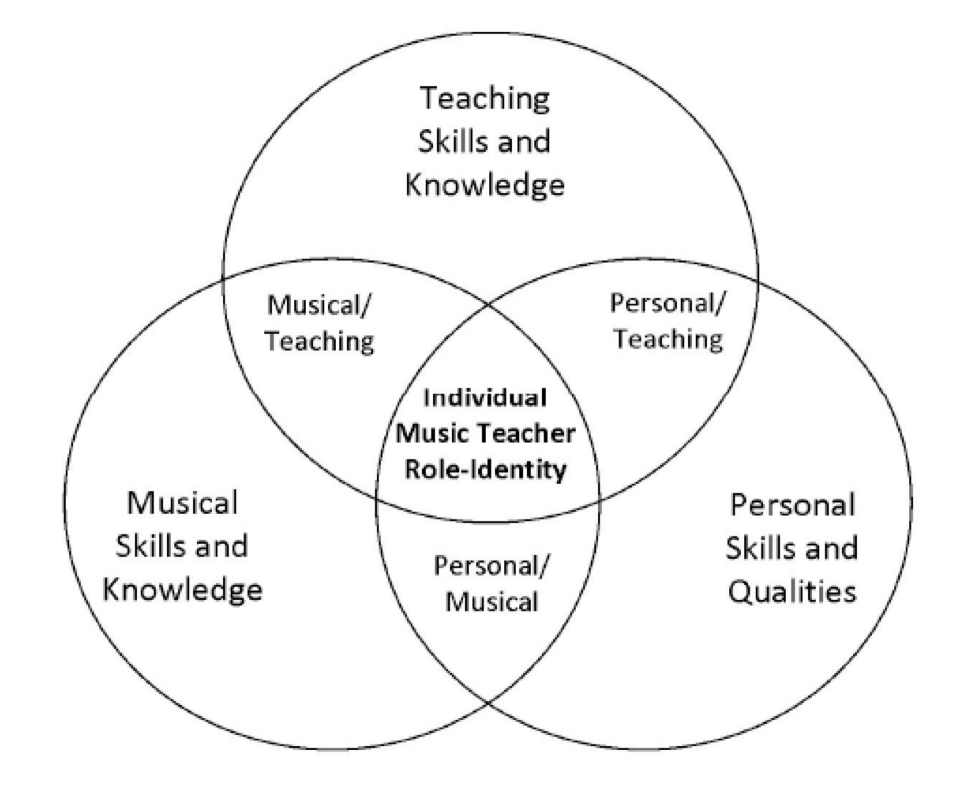

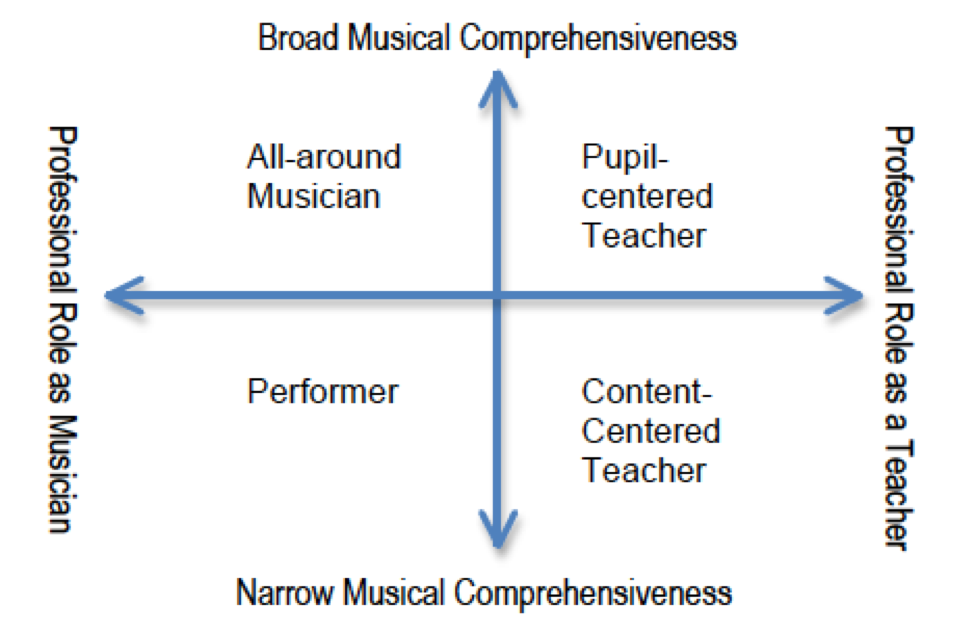

Bouij’s (1998) model of the socialization of Swedish “music-teacher-students” to professional practice and identity contends that students entering the field may be predisposed to be pupil-centered or content-centered in their approaches to teaching, with the musicianly correlates being “all-round musician” and “performer” (25). These salient role-identities (Figure 2) are linked to personality, inasmuch as the former implies an emphasis on interpersonal relationships—education of the whole child through music—while the latter implies a more intrapersonal and objective approach to musical subject matter (25). Both are reflections of the individual’s perception or understanding of educational context and goals. The educational institution and program of studies provide an arena in which students struggle to legitimize their self-perceptions along the lines proposed by Roberts (1991b, 1991c).

Figure 2. Bouij’s (1998) Salient Role Identities

Figure 2. Bouij’s (1998) Salient Role Identities

This struggle for social recognition and status may lead to changes in role-identity, such as occurred with Robert’s (1991b, 1991c) Canadian students when they experienced an identity defeat in pursuit of performance aspirations. In Bouij’s (1998) experience with Swedish students, the more dramatic shift in role-identity from pure performer to pupil-centered teacher was unusual (31). Failing to sustain their identities as performers, they became only teachers or all-around musicians. Draves’ (2014) implementation of Bouij’s (1998) theory of role-identities was found to be inconclusive in exploring music education majors’ perceptions as pre-service music teachers. However, Draves suggests that further research is needed to employ Bouij’s role-identity model to investigate its efficacy with music education students within a variety of social and cultural settings.

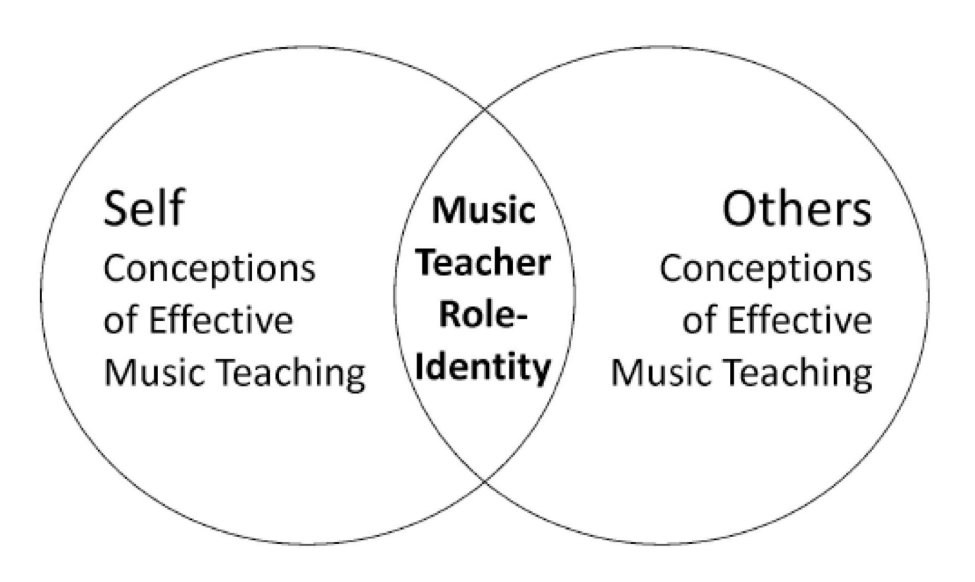

Brewer (2009) proposes that the exploration of conceptions of effective music teaching and the exploration of music teacher role-identity development are very closely related and perhaps inseparable. His premise essentially explores one’s beliefs about the music teacher one wishes or does not wish to become. The three-part model may be used as a tool to examine the “contents of one’s role-identity” (McCall and Simmons 1978) as a music teacher. Figure 3 is a visual representation of the theoretical model (75).

Figure 3. Music Teacher Role Identity Divided into Three Areas

According to Brewer (2009), during our interactions with those who influence our own conceptions of effective music teaching, we become aware of their own conceptions of effective music teaching through observation of their behaviors and gestures, as well as their reactions to our behaviors and gestures, both imagined and real (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Interaction of Self and Others in Role-Identity Development of Music Teachers

Brewer indicates that music teachers develop highly individualized role-identities based on occupational goals and interactions with peers and other teachers. His recommendations for design of music teacher preparation programs include increased efforts to integrate and strengthen connections between pre-service teachers’ experiences inside and outside of the teacher preparation program.

In the examination of the development of occupational role identity (Carper and Becker 1970), meaning is communicated between people through gestures that are common to a reference group. Teachout and McKoy (2009) contend these gestures take the form of specialized content knowledge, skills, behaviors, and physical accoutrements (conducting batons, professional dress, etc.). Those seeking to become a member of a group adopt the gestures of the group. Some members of the reference group exemplify gestures, thus serving as a professional significant other (PSO) to the group members (Teachout and McKoy 2009). The occupational role identity pre-service teachers develop is influenced by their chosen reference group and PSO.

Hargreaves, Purves, Welch, and Marshall (2007) designed a Musical Careers Questionnaire to investigate self-efficacy, occupational identification, and general attitudes towards skills between pre-service music teachers and music majors through a symbolic interactionist framework. In this nine-month longitudinal plan, significant differences were found in three individual items (i.e., musical aims, personal aims, and social aims) relating to the aims of music education. Hargreaves et al. (2007) defined measureable behaviors relating to the construct of teacher self-efficacy as: (a) management of time, (b) perseverance through adversity, (c) security in one’s own abilities, (d) problem-solving abilities, and (e) setting goals and priorities in achievable ways.

Wagoner (2011) examined existing theoretical and research literature to define in-service music teacher identity. Her investigation found that theoretical and epistemological positions may be undefined or absent so that various studies attempting to investigate similar concepts leave much to be inferred by a reader. Music teacher identity is examined in the literature, but common terminology remains vague and undefined. Wagoner (2011) states “Music teacher identity is one’s conception of himself or herself as a music teacher, as affected by five facets: (a) music teacher self-efficacy; (b) music teacher commitment; (c) music teacher agency; (d) music teacher collectivity; and (e) musician-teacher comprehensiveness” (129). Wagoner (2011) found significant differences exist between the constructs of Music Teacher Self-Efficacy and Music Teacher Commitment across all years of teaching experience, situating the music teacher identity definition within a social constructivist theoretical framework (135).

McClellan (2014) examined social identity, value of music education, musician-teacher orientation, and self-concept as music educator through a symbolic interactionist framework. He designed the Undergraduate Music Education Major Identity Survey based on sections of the questionnaire used in L’Roy’s (1983) dissertation The Development of Occupational Identity in Undergraduate Music Education Majors, the Musician-Teacher Orientation Index from Hargreaves’ et al. (2007) Musical Careers Questionnaire, and McClellan’s (2007) Self-Concept As a Music Educator Survey. McClellan (2014) found social identity and musician-teacher orientation contributed to the development of self-concept. Specifically, enthusiasm about being a teacher, social identity while interacting with school children, active involvement in supervised observation and teaching, encouragement to be a teacher by members of the music department community, and value for applied and music education faculty expertise in teaching impact undergraduate music education self-concept as a music educator.

A Theoretical Framework of Identity Construction

The construction of music teacher identity in undergraduate music education majors is an extremely complicated topic requiring examination of several related literatures including sociology, teacher education, psychology, social psychology, and music education (Woodford 2002, 675). The following theoretical models, model attributes, research from which the profession has studied, and definitions based around theoretical and research literature in social identity theory, symbolic interactionism, occupational identity, and role theory were synthesized to propose a social-cognitive theoretical framework of music teacher identity construction.

This section begins with distinct attributes of Bouij’s (1998) theoretical Model of Socialization and Salient Role Identities. Bouij’s (1998) model (Figure 2) is rich in both its theoretical base and multidimensional nature. The sociological dimensions proposed by Bouij in regards to music teacher identity also resonate with themes that have emerged from research efforts in Canada (Roberts 2004), the United Kingdom (e.g., the Teacher Identities in Music Education project – University of Surrey Roehampton), and other European countries (e.g., Mark 1998). The model includes four primary role-identities (a) all-around musician, (b) pupil-centered teacher, (c) performer, and (d) content-centered teacher. These four social constructions are also hypothesized to exist along two theoretical axes. The first axis represents an individuals’ musical self-concept (i.e., all-around musician vs. performer) whereas the second represents whether an individual sees their role in the profession as primarily a teacher or a musician (i.e., pupil- vs. content-centered).

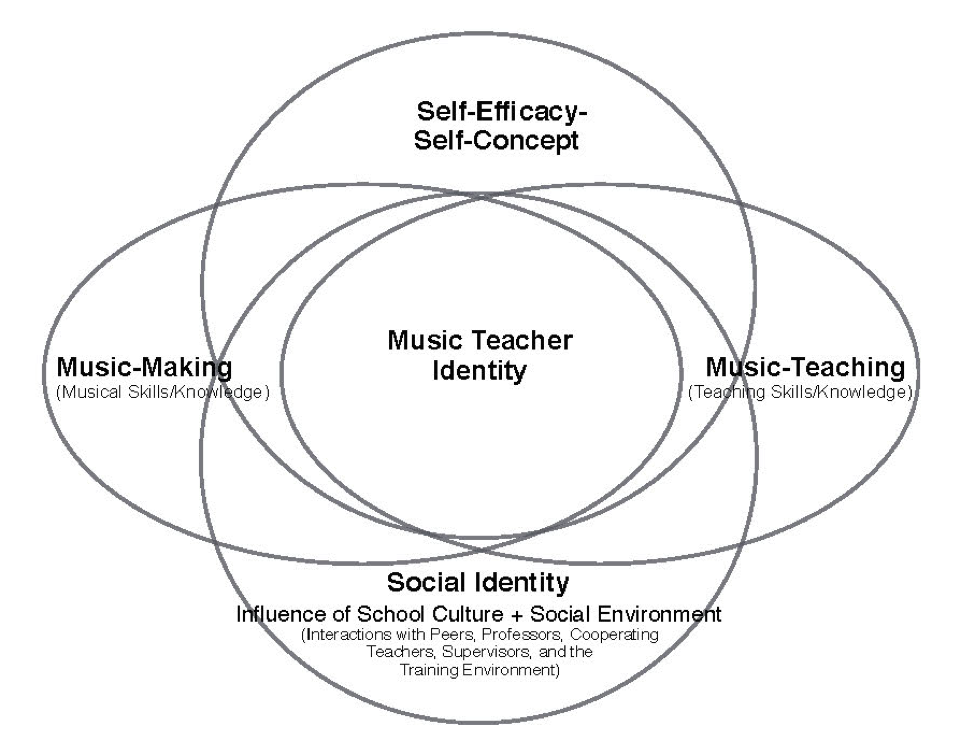

Recent literature has expanded and deepened the profession’s understanding of music teacher identity (Dolloff 2006, 2007; Jorgensen 2006, 2008; Nielsen and Varkøy 2006). As a great deal of research has been devoted to the development of identity as a performer versus identity as a teacher (i.e., two distinct role identities), substantial research supports a theoretical framework of identity construction that centers on the intersection of musician and teacher identity. Some literature suggests that pre- and in-service music teachers seek balanced or integrated identities (Bernard 2004, 2005; Brewer 2009; Dust 2006; Isbell 2006, 2008; Jorgensen 2008; Wilson 1998), in which the performer/musician identity and teacher identity are still addressed as distinct entities in recent research (Dust 2006; Isbell 2006, 2008; Parkes and Jones 2012). However, instead of examining music teacher identity as consisting of separate components of musician and teacher, a theoretical framework of identity construction should center on the intersections of the actions of music-making and music-teaching associated with music teacher identity (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Integrated Model of Music-Making and Music Teaching

Figure 5. Integrated Model of Music-Making and Music Teaching

As White (1967) concludes from his interactionist study of the professional role and status of school music teachers (N=1000) that despite their own belief in the critical role of performance in music education, experienced music educators share more social characteristics in common with teachers than with professional musicians (White 1967, 8; L’Roy 1983, 58). Some kind of balance between and integration of the two role-identities is desirable (Roberts 2000b; Rose 1998; Stubley 1998, 163). Taken together, these roles constitute a social framework for music education thought and practice, and thus also for the personal and professional exploration and growth of music education majors (Woodford 2002, 690).

Significant research has been done on beliefs regarding the salient characteristics of effective teaching. Researchers found undergraduate music education majors, beginning and veteran teachers consistently rated teaching skills higher than musical skills, personality skills or personality characteristics. Rohwer and Henry (2004), Taebel (1980), Teachout (1997), Wayman (2005) have inquired as to which particular sets of skills (e.g., musical, personal, teaching) are valued the most among various music teacher populations. Undergraduate music education students (Teachout 1997, Wayman 2005), experienced music teachers (Taebel 1980, Teachout 1997), and college music educators (Rohwer and Henry 2004) consistently rated teaching skills higher than musical skills, personality skills or personality characteristics in these studies. Teaching competencies consisted of planning skills, pedagogical methods and techniques, use of instructional materials and equipment, communication skills, pupil evaluation and feedback, program and teacher evaluation, professional responsibilities, and control and management skills (Taebel 1980).

Other researchers have found that, when asked open-ended questions regarding salient characteristics of effective teaching, subjects tended to identify musical skills (e.g., Mills and Smith 2003; Sogin and Wang 2002). Sogin and Wang (2002) found that when asked to “explain how you involve your students in values, experiences, insights, imagination, and appreciation through your own teaching” one third of the respondents discussed the ability to model and valuing high quality music as important factors. The respondents also replied that having a ‘student-centered approach’ was important. Mills and Smith (2003) found that when asking a sample of English instrumental music educators (N=138) to recall strengths of the best lessons they received as students, musical skills and characteristics such as ‘teacher demonstrations,’ ‘technical knowledge’ and ‘emphases on tone quality’ were those most commonly cited. Mills and Smith found that the subjects tended to indicate teaching skills such as ‘enthusiasm’ and ‘communication’ as hallmarks for school-age teaching whereas musical skills such as ‘technical focus,’ ‘develop individual voice’ and ‘practice skills’ were more often associated with the hallmarks of good teaching in higher education. Researchers have often divided characteristics of effective music teaching into two or more general categories of musical, teaching, and personal skills, qualities, or knowledge (Baker 1982, DePugh 1987, Doane 1983, Farmilo 1981, Kelly 2008, Rohwer and Henry 2004, Taebel 1980, Teachout 1997).

This research on teaching skills, musical skills, and personality skills or characteristics (Rohwer and Henry 2004, Taebel 1980, Teachout 1997, Wayman 2005) and salient characteristics of effective music teaching (Baker 1982, DePugh 1987, Doane 1983, Farmilo 1981, Kelly 2008, Mills and Smith 2003, Sogin and Wang 2002) share common underpinnings of Brewer’s (2009) Conceptions of Effective Teaching and Role-Identity Development. His integrated model of role-identity is designed to provide increased comprehension of the individualized beliefs associated with identity construction of music teachers.

Brewer (2009) suggests that conceptions of effective teaching and role-identity development are very closely related. Based on the literature, Brewer (2009) devised an analytical model of effective music teaching comprised of three components, (a) personal skills and qualities, (b) teaching skills and knowledge, and (c) musical skills and knowledge that can help provide increased comprehension of individualized beliefs associated with identity construction.

A deeper understanding of role-identity development and its connection to conceptions of effective teaching can help those involved in music teacher education understand the individualized beliefs and subsequent actions associated with music teacher role-identity development. Brewer’s (2009) Integrated Model of Role-Identity in Music Teachers, shown earlier in Figure 3, may represent particular sets of teaching, personal, and musical skills and knowledge examined by researchers (e.g., Mills and Smith 2003, Sogin and Wang 2002, Rohwer and Henry 2004, Taebel 1980, Teachout 1997, Wayman 2005) regarding role-identity development.

Recent research has examined existing theoretical and research literature based around tenets of social theory, symbolic interactionism, and role theory (Hargreaves et al. 2007, McClellan 2014, Wagoner 2011) to define music teacher identity. These definitions provide fundamental constructs important to developing a theoretical framework. Hargreaves et al. (2007) defined measurable behaviors relating to the construct of teacher self-efficacy as management of time, perseverance through adversity, security in one’s own abilities, and problem-solving abilities. Wagoner (2011) defined music teacher identity as one’s conception of himself or herself as a music teacher as affected by music teacher self-efficacy, music teacher commitment, music teacher agency, music teacher collectivity, and music-teacher comprehensiveness (129). McClellan (2014) found social identity and musician-teacher orientation contributed to the development of self-concept as a music educator. Particularly, enthusiasm about being a teacher, social identity while interacting with school children, active involvement in supervised observation and teaching, encouragement to be a teacher by members of the music department community, and value for applied and music education faculty expertise in teaching impact undergraduate music education self-concept as a music educator.

The synthesis of these definitions with identity construction research literature and components of theoretical models of Bouij (1998) and Brewer (2009) provides constructs essential to a social-cognitive theoretical framework (shown in Figure 6) through which the profession may investigate and enhance music teacher identity construction.

Figure 6. Social Cognitive Framework of Music Teacher Identity Construction (McClellan 2017)

Music teacher social identity, self-efficacy and self-concept, and musician-teacher orientation as music teacher were common components to researchers’ definition of music teacher identity. A theoretical framework of music teacher identity construction in the school of music must reflect an intersection of music–making and –teaching roles as well as constructs consistent with occupational identity research and associated with appropriate social theory. Social Identity results from interactions with peers, professors, other teachers, significant others, supervisors, cooperating teachers, commitment of time or value for music education, and the training environment (e.g., influences of the school of music culture and social environment) (Austin et al. 2012; Conkling 2003; Isbell 2008; L’Roy 1983; McClellan 2014; Evans and McPherson 2015; Roberts 1991c, 2000a).

This model is unique in that it integrates distinct common theoretical models, constructs, attributes, and characteristics of music teacher identity research as examined by the profession. Whereas, music teacher identity research has primarily focused on individual constructs of social theories of identity, socialization, social interactions, symbolic interactionism, and occupational identity, this multidimensional model blends research on these constructs, models, and attributes along with musician-teacher role identity, conceptions of effective music teaching, and the exploration of music teacher role-identity development. The complex process of music teacher identity construction requires a combination of all elements into a coherent whole in order to unify both social and cognitive processes. This social-cognitive theoretical framework may serve to ground future research on the multifaceted dimensions of music teacher identity wherein all constructs are integrated, and elements and circumstances can be observed and evaluated or through which it provides a means of measuring social cognitions that may be important in behavior relative to identity.

Conclusion

In order to further the ways through which the profession investigates music teacher identity construction, enhances university teacher training and induction, and enriches the lives of future music educators, it is necessary to identify a theoretical framework in social-cognitive theory as a foundation for definition of identity construction in the music teacher education program. Music teacher self-efficacy and self-concept, musician-teacher orientation, intersections of music-making and music-teaching roles as music teacher, social identity resulting from interactions and influences in the school of music culture and social environment, and commitment of time in demonstrating value for music education in the training environment are common components to this social-cognitive framework of music teacher identity construction.

The proposed social-cognitive theoretical framework within this study might further the ways through which the profession investigates music teacher identity construction in the music teacher education program. Although there are many psychological influences on people’s actions and achievements, self-efficacy or confidence in one’s own ability to achieve intended results has been shown to have the greatest predictive power of attainment (Zimmerman et al. 1992). Self-concept as music educator encompasses one’s sense of competence, feelings regarding abilities, and possession of dispositions necessary to be a qualified music teacher (McClellan 2007, 2011). Musician-teacher orientation represents the level of identification to the profession of music and teaching (Hargreaves et al. 2007). Austin, et al. (2012) defines occupational identity as “a merger of teacher-musician and self-other dimensions” (81).

Future research should be designed to examine multidimensional components of identity construction of music education majors in the teacher education program. By investigating such attributes as self-efficacy, self-concept, integration of musician-teacher role identities, and conceptions of effective music teaching, music teacher educators may gain a more global view of music teacher identity of university music education majors. Furthermore, examining the relationships, interactions, and synergy among elements of this theoretical framework will provide a much deeper understanding of music teacher identity from which music teacher educators may approach revising, changing, or enhancing practices in pre-service music teacher education and training.

This social-cognitive theoretical framework may serve to ground future research on music teacher identity through constructs which may be examined by means of both quantitative and qualitative measures. The complex multidimensional design of this theoretical framework makes possible opportunities to use both quantifiable and descriptive measures. Whereas, each component may be examined through computable means, there are also ways in which qualitative measures may be used to observe and evaluate circumstances that influence music teacher identity construction. Researchers should consider approaches that will make use of either and/or both types of measures to investigate elements in this theoretical framework. By making use of single method and mixed designs, research may investigate complex facets of this multidimensional social-cognitive framework that provide information relevant to music teacher preparation and induction into the profession.

According to Berzonsky’s (2004) social-cognitive model, identity is conceptualized as a structure as well as a process. As a process, identity directs and governs the resources adolescents use to cope and adapt in everyday life (Berzonsky 1990, 2004, 304).

Current music teacher identity construction research has not considered social cognition and the cognitive process in the maintenance and/or reconstruction of identity during education and training throughout the music teacher education program. Music teacher identity is fluid over time, contexts, and impacted by individual experiences (Chreim et al. 2003, Wagoner 2014, Wenger 1998). Recognizing the impact of social cognition and the cognitive process on music teacher identity construction, it is important to consider Berzonsky’s (2008) model (Figure 1) while using this proposed social-cognitive framework to examine the continual construction and/or reconstruction of music teacher identity. Consideration of this projected social-cognitive framework as self-elements and identity status within Berzonsky’s model (Figure 7) would provide for investigation of the cognitive processes and identity processing styles of pre-service music teachers as they go through the process of identity formation in which identity may be examined as a structure as well as a process.

Figure 7. McClellan’s Social Cognitive Theory of Music Teacher Identity Construction (2017) within Berzonsky’s (2008) Adapted Model of Relationships Between Cognitive Processes

As adolescents within various identity statuses differ in the social cognitive processes they use to solve problems, make decisions, and process identity-relevant information, examining stylistic differences in how students negotiate the challenge of constructing and/or reconstructing their sense of identity (Berzonsky 2010, 13) may present new insights into the social origin of undergraduates music education majors’ thinking, behavior, and cognitive processes by which pre-service music teachers construct and reconstruct their sense of identity (Berzonsky 1988, 1993). Therefore, the investigation of elements of this social-cognitive theoretical framework through these cognitive processes will inform music teacher educators in ways that will help them enrich professional practice, university teacher training and induction, and the preparation of future music educators.

In similar manner, application of this social-cognitive framework as self-elements and identity status within Berzonsky’s model (Figure 7) in the examination of beginning and in-service music teachers’ identity construction would provide the music education profession with much deeper understanding of the cognitive processes and identity processing styles of in-service music teachers as they go through the process of continual reconstruction of music teacher identity in the workplace. Accordingly, research of beginning and in-service music teacher identity based in elements of this social-cognitive theoretical framework would provide the profession deeper understanding, which may benefit professional development and retention of music educators in the teaching profession.

Therefore, the proposed social-cognitive theoretical framework within this study might further the ways through which the profession investigates music teacher identity construction, enhance university teacher training and induction, and enrich the lives of future music educators. Such a framework may also be of value to the music education profession by informing enhanced professional development and music teacher retention practice. Hence, this social-cognitive theoretical framework may serve to ground future research on the multifaceted dimensions of music teacher identity that benefit music teacher preparation and the music teaching profession.

About the Author

Edward McClellan is the Mary Freeman Wisdom Distinguished Professor of Music, Associate Professor and Division Coordinator of Music Education at Loyola University New Orleans. Dr. McClellan is member of the Editorial Review Board for Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education journal, TOPICS, the Editorial Committee of the Music Educator Journal, and Chair of the Perception and Cognition Special Research Interest Group (SRIG) of the National Association for Music Education. Dr. McClellan has published research in the Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education, Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, Contributions to Music Education, and Music Educators Journal.

References

Adams Gerald R., Michael D. Berzonsky, and Leo Keating. 2006. Psychosocial resources in first-year university students: The role of identity processes and social relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 35: 81–91.

Adams, Gerald R., Brenda Munro, Maryanne Doherty-Poirer, Gordon Munro, Anne-Mette R. Petersen, & Joy Edwards. 2002. Diffuse/avoidance, normative, and informational identity styles: Using identity theory to predict maladjustment. Identity 1: 307–320.

Augoustinos, Martha, and Iain Walker. 1995. Social cognition: An integrated introduction. London: Sage.

Austin, James. R., Daniel S. Isbell, and Joshua A. Russell. 2012. A multi-institution exploration of secondary socialization and occupational identity among undergraduate music majors. Psychology of Music 40 (1): 66–83. doi:10.1177/0305735610381886

Austin, James. R., & Peter Miksza. 2009. Trying on teaching. Paper presented at the Society for Music Teacher Education Biennial Symposium, Greensboro, NC.

Baker, Patricia J. 1982. The development of music teacher checklists for use by administrators, music supervisors, and teachers in evaluating music teaching effectiveness. Doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon.

Bandura, Albert V. 1986. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, Albert. 1989. Multidimensional scales of perceived self-efficacy. Unpublished test, Stanford University, Stanford, CA.

Bandura, Albert V. 1997. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Bart Soenens, Michael D. Berzonsky, and Dennis R. Papini. 2015. Attending to the role of identity exploration in self-esteem: Longitudinal associations between identity styles and two features of self-esteem. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 1–11. doi:10.1177/0165025415602560

Baum, Steven K. 2008. The psychology of genocide: Perpetrators, bystanders, and rescuers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Berg, Margaret H. 2010. Sampling from the mentoring buffet: A case study of mentoring in a middle school wind ensemble outreach program. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Denver, CO.

Bernard, Rhoda. 2004. Striking a chord: Elementary general music teachers’ expressions of their identities as musician-teachers. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University.

Bernard, Rhoda. 2005. Making music, making selves: A call for reframing music teacher education. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 4 (2), 1–36. https://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Bernard4_2.pdf

Bernard, Rhoda. 2007. Multiple vantage points: The author’s reply. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 6 (1), 1–15. https://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Bernard6_1.pdf

Berzonsky, Michael D. 1986. A measure of identity style: Preliminary findings. Paper presented at the meetings of the Society for Research on Adolescence, Madison, WI.

Berzonsky, Michael D. 1988. Self-theorists, identity status, and social cognition. In Self, ego, and identity: Integrative approaches, edited by D. K. Lapsley and F. C. Power. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Berzonsky, Michael D. 1989. Identity style: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Adolescent Research 4 (3): 268–82.

Berzonsky, Michael D. 1990. Self-construction over the life-span: A process perspective on Identity formation. In Advances in personal construct psychology, Vol. 1, edited by G. J. Neimeyer and R. A. Neimeyer, 155–86. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Berzonsky, Michael D. 1993. A constructivist view of identity development: People as post-positivist self-theorists. In Discussions on ego identity, edited by J. Kroger, 169–83. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Berzonsky, Michael D. 1998. Psychosocial development in early adulthood: The transition to university. Paper presented at the Biennial Meetings of the International Society for the Study of Behavioural Development, Berne, Switzerland.

Berzonsky, Michael D. 2003. Identity style and well-being: Does commitment matter? Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research 3: 131–42.

Berzonsky, Michael D. 2004. Identity processing style, self-construction, and personal epistemic assumptions: A social-cognitive perspective. European Journal of Developmental Psychology 1 (4): 303–315.

Berzonsky Michael D. 2008. Identity Formation: The Role of Identity Processing Style and Cognitive Processes. Personality and Individual Differences 44: 643–53.

Berzonsky, Michael D. 2010. Cognitive processes and identity formation: The mediating role of identity processing style. Psychologia Rozwojowa 15 (4): 13–27.

Berzonsky, Michael D. 2011. A social-cognitive perspective on identity construction. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Maintained and operated by Research, edited by Seth J. Schwartz, Koen Luyckx and Vivian L. Vignoles, 55–76. Springer Science+Business Media.

Berzonsky Michael D., Susan J. T. Branje, and Wim Meeus. 2007. Identity processing style, psychosocial resources, and adolescents perceptions of parent-adolescent relations. Journal of Early Adolescence 27: 324–335.

Berzonsky, Michael D., and Linda S. Kuk. 2000. Identity status, identity processing style, and the transition to university. Journal of Adolescent Research 15: 81–98.

Beynon, Carol. 1998. From music student to music teacher: Negotiating an identity. In Critical thinking in music: Theory and practice. Studies in Music from the University of Western Ontario 17, edited by Paul Woodford, 83–105.

Blumer, Herbert. 1969. Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bouij, Christer. 1998. Swedish music teachers in training and professional life. International Journal of Music Education 32: 24–31.

Brewer, Marilyn B., Miles Hewstone, eds. 2004. Applied social psychology: Perspectives on social psychology. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Brewer, Wesley D. 2009. Conceptions of effective teaching and role-identity development among preservice music educators. Doctoral diss., Arizona State University.

Brubaker, Rogers, and Frederick Cooper. 2000. Beyond identity. Theory and Society 29: 1–47.

Caputi Peter, and Lindsay Oades. 2001. Epistemic assumptions: Understanding self and the world (A note on the relationship between identity style, world view and constructivist assumptions using an Australian sample). Journal of Constructivist Psychology 14: 127–34.

Carper, James. 1970. The elements of identification with an occupation. In Sociological work, edited by Howard S. Becker. Chicago: Aldine.

Carper, James, and Howard S. Becker. 1970. The elements of identification with an occupation. In Sociological work, edited by Howard S. Becker, 189–201. Chicago: Aldine.

Celen, Hacer, N., and Muharrem E. Kusdil. 2009. Parental control mechanisms and their reflection on identity styles of Turkish adolescents. Paideia 19: 7–16.

Cheek, Jonathan M. 1989. Identity orientations and self-interpretation. In Personality psychology: Recent trends and emerging directions, edited by D.M. Buss and N. Cantor, 275–85. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Chreim, Samia, Bernie Williams, Edna Djokoto-Asem, and Linda Janz. 2003. Professional identity under reconstruction: A case study of changes in a physician-dominated health unit. Abstract of presentation made at the Administrative Science Association of Canada, Halifax, Canada.

Colwell, Richard, and Carol Richardson, eds. 2002. The new handbook of research on music teaching and learning. New York: Schirmer Books.

Conkling, Susan. 2003. Uncovering preservice music teachers’ reflective thinking: Making sense of learning to teach. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 155: 11–23.

Côté, James E. 2006. Identity studies: How close are we to establishing a social science of identity? An appraisal of the field. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research 6: 3–25.

Côté, James E. 2009. Identity formation and self-development in adolescence. In Handbook of adolescent psychology, edited by R. Learner and L. Steinberg, 159–87. New York: Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy001010

Crocetti, Elisabetta, Monica Rubini, Michael D. Berzonsky, and Wim Meeus. 2009. The identity style inventory: Validation in Italian adolescents and college students. Journal of Adolescence 32: 425–33.

Doane, Christopher. 1983. The identification and assessment of selected characteristics of prospective music educators. Contributions to music education 10 (1): 9–19.

Dollinger, Stephanie M. 1995. Identity styles and the five-factor model of personality. Journal of Research in Personality 29: 475–9.

Dolloff, Lori-Anne. 2006. Celebrating and nurturing the identity of the musician/teacher. In Music and human beings: Music and identity, edited by B. Stålhammar, 123–36. Orebro, Sweden: Universitetsbiblioteket.

Dolloff, Lori-Anne. 2007. All the things we are: Balancing our multiple identities in music teaching. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 6 (1): 1–21. Retrieved from https://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Dolloff6_1

Draves, Tami. J. 2014. Under construction: Undergraduates’ perceptions of their music teacher role-identities. Research Studies in Music Education 36 (2): 199–214. doi:10.1177/1321103X14547982

Dust, Laura J. 2006. The negotiation and reconciliation of musician and teacher identities. Doctoral dissertation, University of Alberta, Canada.

DePugh, Dana L. 1987. Characteristics of successful senior high school choral directors in the state of Missouri: A survey of teacher self-perception and student and administrator assessment. Doctoral diss., University of Missouri.

Duriez Bart, Bart Soenens, and Wim Beyers. 2004. Religiosity, personality, and identity styles: An integrative study among late adolescents in Flanders (Belgium). Journal of Personality 72: 877–910.

Ellemers, Naomi, Russell Spears, and Bertjan Doosje. 2002. Self and social identity. Annual Review of Psychology 53: 161–86.

Erikson, Erik H. 1950. Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Erikson, Erik H. 1964. Insight and responsibility. New York: Norton.

Erikson, Erik H. 1968. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Evans, Paul, and Gary McPherson. 2015. Identity and practice: The motivational benefits of a long-term musical identity. Psychology of Music 43 (3): 407–22. doi:10.1177/0305735613514471

Farmilo, Norma R. 1981. The creativity, teaching style, and personality characteristics of the effective elementary music teacher. Doctoral diss., Wayne State University.

Fiske, Susan. T., and Shelley E. Taylor. 1991. Social cognition. Second edition. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Froehlich, Hildegard. 2007. Sociology for music teachers. Perspectives for practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice-Hall.

Froehlich, Hildegard, and Diann L’Roy. 1985. An investigation of occupancy identity in undergraduate music education majors. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 85: 65–75.

Grotevant, Harold D. 1987. Toward a process model of identity formation. Journal of Adolescent Research 2: 203–22.

Hargreaves, David J., Ross M. Purves, Graham F. Welch, and Nigel Marshall. 2007. Developing identities and attitudes in musicians and classroom teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology 77: 665–82.

Harwood, Eve. 1993. Learning characteristics of college students: Implications for the elementary music education methods class. Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning 4 (1): 13–19.

Haston, Warren, and Joshua A. Russell. 2012. Turning into teachers: The influences of authentic context learning experiences on the occupational identity development of preservice music teachers. Journal of Research in Music Education 59: 369–392. doi:10.1177/0022429411414716

Hejazi Elaheh, Mehrnaz Shahraray, Masomeh Farsinejad, and Ali Asgary. 2009. Identity styles and academic achievement: Mediating role of academic self-efficacy. Social Psychology of Education 12: 123–35.

Hitlin, Steven A. 2003. Values as the core of personal identity: Drawing links between two theories of self. Social Psychology Quarterly 66: 118–37.

Hourigan, Ryan, and Linda Thornton. 2009. Understanding identity and socialization development in professional education programs: Lessons learned from across campus. Paper presented at the Instrumental Music Teacher Educators Biennial Symposium, Deer Creek, OH.

Isbell, Daniel S. 2006. Socialization and occupational identity among preservice music teachers enrolled in traditional baccalaureate degree programs. Doctoral diss., University of Colorado at Boulder.

Isbell, Daniel. 2008. Musicians and teachers: The socialization and occupational identity of preservice music teachers. Journal of Research in Music Education 56: 162–78. doi:10.1177/0022429408322853

Jorgensen, Estelle. 2006. Toward a social theory of musical identities. In Music and human beings: Music and identity, edited by B. Stålhammar, 27–44. Orebro, Sweden: Universitetsbiblioteket.

Jorgensen, Estelle R. 2008. The art of teaching music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Jorgensen, Carsten R. 2009. Identity style in patients with borderline personality disorder and normal controls. Journal of Personality Disorders 23: 101–12.

Kelly, Steven. 2008. High school instrumental students’ perceptions of effective music student teacher traits. Journal of Music Teacher Education 17 (2): 83–91. doi:10.1177/1057083708317648

Krettenauer, Tobias. 2005. The role of epistemic cognition in adolescent identity formation: Further evidence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 34: 185–98.

Kroger, Jane. 2007. Identity: The balance between self and other. London: Routledge.

Kroger, Jane, and James E. Marcia. 2011. The identity statuses: Origins, meanings, and interpretations. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research, edited by S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, and V. L. Vignoles, 31–53.

L’Roy, Diann. 1983. The development of occupational identity in undergraduate music education majors. Doctoral diss., University of North Texas, Denton.

Luyckx, Koen, Luc Goossens, Bart Soenens, and Wim Beyers. 2006. Unpacking commitment and exploration: Validation of an integrative model of adolescent identity formation. Journal of Adolescence 29: 361–78.

Macek Petr, and Lida Osecka. 1996. The importance of adolescents’ selves: Description, typology, and context. Personality and Individual Differences 21: 1021–7.

Maddux, James E. 1993. Social cognitive models of health and exercise behaviour: An introduction and review of conceptual issues. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. Special the application of social psychological theories to health and exercise 5: 116–40.

Maddux, James E., and Jennifer T. Gosselin. 2003. Self-efficacy. In Handbook of self and identity, edited by M.R. Leary and J.P. Tangney, 218–38. New York: Guilford Press.

Marcia, James E. 1966. Development and validation of ego identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 3: 551–8.

Marcia, James E. 1980. Identity in adolescence. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, edited by J. Adelson, 159–87. New York: Wiley.

Marcia, James E. 1988. Common processes underlying ego identity, cognitive/moral development, and individuation. In Self, ego, and identity: Integrative approaches, edited by D. K. Lapsley and F. C. Power, 211–25. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Mark, Desmond. 1998. The music teacher’s dilemma: musician or teacher? International Journal of Music Education 32: 3–23.

McCall George J., and Jerry L. Simmons. 1978. Identities and interactions: An examination of human associations in everyday life. New York: Free Press.

McClellan, Edward R. 2007. Relationships among parental influences, selected demographic factors, adolescent self-concept as a future music educator, and the decision to major in music education. Doctoral diss., The University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

McClellan, Edward R. 2011. Relationships among parental influences, selected demographic factors, adolescent self-concept as a future music educator, and the decision to major in music education. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 187: 49–64.

McClellan, Edward R. 2014. Undergraduate music education major identity formation in the university music department. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 13 (1): 274–303. https://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/

McClellan13_1.pdf

Mills, Janet, and Jan Smith. 2003. Teachers’ beliefs about effective instrumental teaching in schools and higher education. British Journal of Music Education 20 (1): 5–27.

Moshman, David. 2007. Us and them: Identity and genocide. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research 7: 115–35.

Mueller, Renate. 2002. Perspectives from the sociology of music. In The new handbook of research on music teaching and learning, edited by R. Colwell and C. Richardson, 584–603. New York: Oxford University Press.

Munoz Garcia, Mónica I. 1998. La identidad adolescente: Estudio empirico dirigido a la elaboracion de una primera adaptacion del inventario de estilo de identidad de Michael D. Berzonsky. Doctor diss., Universidad Pontificia De Salamanca.

Nielsen, Frederik Pio, and Øivind Varkøy. 2006. On the relation between music and man: Is there a common basis, or is it altogether individually and socially constructed? In Music and human beings: Music and identity, edited by B. Stålhammar, 163–82. Orebro, Sweden: Universitetsbiblioteket.

Nevid, Jeffrey S. 2009. Psychology: Concepts and applications. Third edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Nurmi Jari-Erik, Michael D. Berzonsky, Kaisa Tammi, and Andrew Kinney. 1997. Identity processing orientation, cognitive and behavioral strategies, and well-being. International Journal of Behavioral Development 21: 555–70.

Oyserman, Daphna, and Leah James. 2011. Possible identities. In Handbook of identity research, edited by S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx and V. L. Vignoles, 117–45. New York, NY: Springer.

Parkes, Kelly A., and Brett D. Jones. 2012. Motivational constructs influencing undergraduate students’ choices to become classroom music teachers or music performers. Journal of Research in Music Education 60: 101–23.

Paul, Stephen J. 1998. The effects of peer teaching experiences on the professional teacher role development of undergraduate instrumental music education majors. Bulletin of the Council of Research in Music Education 137: 73–92.

Paul, Stephen. J., and Jeanne H. Ballentine. 2002. The sociology of education and connections to music education research. In The new handbook of research on music teaching and learning: A project of the music educators national conference, edited by R. Colwell and C. Richardson, 566–83. New York: Oxford Press.

Prescesky, Ruth E. 1997. A study of preservice music education students: Their struggle to establish a professional identity. Doctoral diss., McGill University.

Roberts, Brian A. 1991a. A place to play: The social world of university schools of music. St. John’s, NFLD: Memorial University of Newfoundland, Faculty of Education.

Roberts, Brian A. 1991b. Sociological reflections on methods in school music. Canadian Music Educator 21 (5): 20–25.

Roberts, Brian A. 1991c. Music teacher education as identity construction. International Journal of Music Education 18: 30–39.

Roberts, Brian A. 1991d. Musician: A Process of Labelling. St. John’s, NFLD: Memorial University of Newfoundland, Faculty of Education.

Roberts, Brian A. 1993. I, Musician: Towards a model of identity construction and maintenance by music education students as musicians. St. John’s, NFLD: Memorial University of Newfoundland, Faculty of Education.

Roberts, Brian A. 2000a. Gatekeepers and the reproduction of institutional realities: The case of music education in Canadian universities. Musical Performance 2 (3): 63–80.

Roberts, Brian A. 2000b. A North American response to Bouij: Music education student identity construction revisited in Sweden. Spoken Paper at On the Sociology of Music Education II: Papers from the symposium at the University of Oklahoma.

Roberts, Brian A. 2000c. The sociologist’s snare: Identity construction and socialization in music. International Journal of Music Education 35: 54–8.

Roberts, Brian 2004. Who’s in the mirror? Issues surrounding the identity construction of music educators. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 3(2), 1–42. https://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Roberts3_2.pdf

Rohwer, Debbie, and Warren Henry. 2004. Requisite skills and characteristics of effective music teachers. Journal of Music Teacher Education 13 (2): 18–27.

Rose, Andrew M. 1998. Exploring music teacher thinking: A reflective and critical model. In Critical thinking in music: Theory and practice, edited by Paul Woodford. Studies in Music from the University of Western Ontario 17: 23–44.

Russell Joshua. 2012. The occupational identity of in-service secondary music educators: Formative interpersonal interactions activities. Journal of Research in Music Education 60 (2): 145–65.

Sallay, Hedvig. 2002. Identity styles in focus: Their relation to parenting and their role in the development of openness and need for cognition. Paper Presented at the Meetings of the European Association for Research on Adolescence, Oxford, England.

Schildkraut, Deborah J. 2007. Defining American identity in the twenty-first century: How much “there” is there? The Journal of Politics 69: 597–615.

Schwartz, Seth J., Curtis S. Dunkel, and Alan S. Waterman. 2009. Terrorism: An identity theory perspective. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 32: 537–59.

Seabl, Joseph. 2009. Relating identity processing styles to commitment and self-esteem among college students. Journal of Psychology in Africa 19: 309–314.

Sedikides, Constance, and Marilyn B. Brewer. 2001. Individual self, relational self, collective self. Philadelphia: Psychology Press.

Senejko, Alicja. 2007. Style kształtowania tożsamości u młodzieży a ustosunkowanie wobec zagrożeń [Identity styles of adolescents and their attitudes toward threats] In Tożsamość a współczesność [Identity in the Present Day], edited by B. Harwas-Napierała and H. Liberska, 101–128. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM.

Shahram Vaziria, Farah Lotfi Kashania , Zahra Jamshidifara, and Yashar Vaziri. 2014. Brief report: The Identity Style Inventory-validation in Iranian college students. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 128: 316–20.

Soenens, Bart, Michael D. Berzonsky, and Dennis R. Papini. 2015. Attending to the role of identity exploration in self-esteem: Longitudinal associations between identity styles and two features of self-esteem. International Journal of Behavioral Development 40 (5): 1–11. doi:10.1177/0165025415602560

Sogin, David, and Cecilia Wang. 2002. An exploratory study of music teachers’ perception of factors associated with expertise in music teaching. Journal of Music Teacher Education 12 (1): 12–18. doi:10.1177/10570837020120010101

Sramova, Blandina, and Katarina Fichnova. 2008. Identity and creative personality. Studia Psychologica 50: 357–69.

Srivastava, Rakesh K. 1993. Cultural contexts and identity style. Indian Journal of Psychology 68: 35–44.

Stets, Jan E. 2006. Identity theory. In Contemporary social psychological theories, edited by Peter J. Burke, 88–110. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Strachan, Shaelyn M. 2005. An identity theory and social cognitive theory examination of the role of identity in health behaviour and behavioural regulation. (Order No. NR12163). Doctoral diss., University of Waterloo, Canada.

Stryker, Sheldon. 1980. Symbolic interactionism: A social structural version. Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin–Cummings

Stryker, Sheldon. 2003. Whither symbolic interaction? Reflections on a personal odyssey. Symbolic Interaction 26: 95–109.

Stubley, Eleanor. 1998. Thinking critically or thinking musically: Defining musical performance as subject matter. In Critical thinking in music: Theory and practice, edited by P. Woodford. Studies in Music from the University of Western Ontario 17: 157–72.

Taebel, Donald. 1980. Public school music teachers’ perceptions of the effect of certain competencies on pupil learning. Journal of Research in Music Education 28 (3): 185–97.

Teachout, David. 1997. Preservice and experienced teachers’ opinions of skills and behaviors important to successful music teaching. Journal of Research in Music Education 45 (1): 41–50.

Teachout, David J., and Connie L. McKoy. 2009. The effect of teacher role-development training on the teaching effectiveness, motivation, and confidence of undergraduate music education majors: A preliminary study. Paper presented at the MENC/SRME Research Symposium II, Washington DC.

Vaziria, Shahram, Farah Lotfi Kashania, Zahra Jamshidifara, and Yashar Vaziri. 2014. Brief report: The Identity Style Inventory-validation in Iranian college students. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 128, 316–320.

Vignoles, Vivian. L., Camillo Regalia, Claudia Manzi, Jen Golledge, & Eugenia Scabini. 2006. Beyond self-esteem: Influence of multiple motives on identity construction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90 (2): 308–333.

Vignoles, Vivian L., Seth J. Schwartz, & Koen Luyckx. 2011. Introduction: Toward an integrative view of identity. In Handbook of identity theory and research, edited by Seth J. Schwartz, Koen Luyckx, and Vivian L. Vignoles, 1–27. New York: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_1

Vleioras, Georgios, and Hark A. Bosma. 2005. Are identity styles important for psychological well-being? Journal of Adolescence 28: 397–409.

Wagoner, Cynthia. 2011. Defining and measuring music teacher identity: A study of self-efficacy and commitment among music teachers. Doctoral diss., University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Wagoner, Cynthia L. 2014. Defining music teacher identity for effective research in music education. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the ISME World Conference and Commission Seminars, Thessaloniki Concert Hall, Thessaloniki, Greece. http://citation.allacademic.com/meta/p548496_

index.html

Wayman, Virginia. 2005. Beginning music education students’ and student teachers’ opinions of skills and behaviors important to successful music teaching. Contributions to Music Education 33 (1): 27–40.

Wenger, Etienne. 1998. Communities of practice: Learning meaning and identity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

White, Howard G. 1967. The professional role and status of music educators in the United States. Journal of Research in Music Education 15 (1): 3–10.

Wilson, Laura E. 1998. The experiences of music teacher/performers in public schools. Doctoral diss., New York University.

Wolfgang, Ralph E. 1990. Early field experience in music education: A study of teacher role socialization (preservice teachers). Doctoral diss., University of Oregon.

Woodford, Paul. 2002. The social construction of music teacher identity in undergraduate music education majors. In The new handbook of research on music teaching and learning: A project of the music educators national conference, edited by R. Colwell and C. Richardson, 675–694. New York: Oxford Press.

Xu, Shejiao. 2009. What are the relations between identity styles and adolescences’ academic achievement? A study of college students at a private university in China. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 14: 299–311.

Zimmerman, Barry J., Albert Bandura, and Manuel Martinez-Pons. 1992. Self-motivation for academic attainment: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. American Educational Research Journal 29 (3): 663–76.