LORENZO SÁNCHEZ-GATT

Michigan State University (USA)

November 2023

Published in Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 22 (4): 131–58. [pdf] https://doi.org/10.22176/act22.4.131

Abstract: I argue that an analysis of antiblack racism in music education discourse is crucial in identifying and addressing potential for harm in the music classroom. I contend that Black children are particularly, and regularly, subjected to poor stereotypical depictions of their identity in digital media. Furthermore, I contend that this digital socialization has far-reaching implications in school. I use the framework of Black Critical Theory (BlackCrit) to explore interpersonal, curricular, and environmental sites of antiblack assault that are commonplace in schools and, specifically, music classrooms. Using a selection of Janelle Monáe’s music, I explore themes of resistance and affirmation through an Afrofuturist lens. I conclude my paper by proposing that Afrofuturism can serve as a disruption that may create sites of affirmation for Black children.

Keywords: Afrofuturism, Critical Race Theory, antiblackness, Black Critical Theory (BlackCrit), socialization, science fiction, popular music education, Janelle Monáe

Numerous mass crises are occurring on a global scale. Fraught global relations resulting from Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, the COVID-19 pandemic, climate crises, political unrest, and structural racism intersect at this specific point in time. These crises affect everyone, yet I cannot help but think about how these events unfold for Black folks specifically. My social position as a queer Afro-Latiné person has made me personally aware of the outcome differential people of color experience. Black people have been more adversely affected in these crises, ranging from higher instances of police brutality against Black bodies; to increased obstacles to fleeing Ukraine (Bowleg et al. 2022; Ibrahim 2022). The insidious manifestation of global antiblackness[1] is the common thread between these seemingly disconnected events (Busey and Dowie-Chin 2021).

Moments of global uncertainty create possibilities for epistemological breaks. These breaks allow us to re-examine and reshape perspectives. My capacity as a music education researcher compels me to wonder, how can music education better serve Black children? I contend that an analysis of antiblackness must be present in music education to better serve Black children. In this paper, I use Black Critical Theory (BlackCrit) to explore the various sites of antiblackness children are exposed to incessantly. I continue by introducing Afrofuturism, a diasporic Afrocentric aesthetic originating in science fiction, as an entry point for BlackCrit praxis. I then examine Janelle Monáe’s concept albums through an Afrofuturist lens for counternarrative and possibility; and their implications for music education.

BlackCrit

Dumas and ross[2] (2016) theorize Black Critical Theory (BlackCrit) as an extension of Critical Race Theory (CRT); and as a way of examining antiblackness more specifically. CRT was co-opted into education research by Gloria Ladson-Billings and William Tate (1995) in the mid-1990s, though its legal roots date back to the 1970s. CRT has been used in education to examine structural racism and the ways in which white supremacy functions in schools. It is guided by five tenets that include: (a) the endemic nature of racism; (b) interest convergence in instances of racial progress; (c) anti-essentialism; (d) value of experiential knowledge; and (e) multidisciplinary scholarship (Dixson and Rousseau 2005; Ladson-Billings and Tate 1995; Solórzano and Delgado Bernal 2001). BlackCrit was developed to examine how blackness interacts with different structures with increased specificity (Dumas and ross 2016).

Dumas and ross (2016) assert that BlackCrit is needed to understand “how Black bodies become marginalized, disregarded, and disdained” (417). They propose three framing ideas to conceptualize BlackCrit: (a) antiblackness as endemic; (b) blackness at tension with the “neoliberal-multicultural imagination”; and (c) the space needed for Black liberatory fantasy (Dumas and ross 2016). I utilize these framings to: (a) highlight the endemic nature of antiblackness in music classrooms; (b) analyze how blackness is at tension with the neoliberal-multicultural imagination; and (c) examine how Janelle Monáe’s artistic output provides insight into the potential for BlackCrit praxis.

Endemic Antiblackness

Endemic Antiblackness: Socialization

Dumas and ross (2016) contend that antiblackness is endemic to American society. The prevalence of antiblackness in media and the increasingly connected nature of society creates an incessant climate of psychological violence for Black children in the United States (Adams-Bass et al. 2014), since digital consumption of media— including entertainment, advertising, and social media platforms—is an increasingly present source of socialization in the lives of children (Prot et al. 2015). Black children are regularly exposed to racist stereotypes in the media, colorism, invisibility, and marginalized speech through online interactions (Adams-Bass et al. 2014; Butkowski et al. 2022; Preston 2021). The antiblack socialization children consume online is further cemented through environmental factors and interactions both in school and outside of school.

Antiblack stereotypes in the U.S. entertainment industry date back to blackface minstrelsy in the 19th century, when “seemingly harmless” tropes such as the blackface characters of Jim Crow and Zip Coon were a common source of entertainment (Lott 2013). These stereotypes still exist in the form of violent, lazy, and uncivilized depictions of Black men, while Black women are stereotyped as loud, domineering, and hypersexualized (Adams-Bass et al. 2014). Adams-Bass et al. (2014) conducted a research study examining how negative stereotypes of Black people influence Black children. His findings highlight that a lower awareness of Black history and racial literacy caused participants to be less likely to identify racial stereotypes and to accept stereotypical images as accurate depictions of Black people. These negative stereotypes may be exacerbated for representations of darker-skinned people due to colorism, the preferential emphasis given to lighter-skinned Black bodies that more closely approximate whiteness (Butkowski et al. 2022). This preference implies that humanity and value are constructed through whiteness, or to say it differently, they are constructed as human and valuable because they are further from blackness.

It is important to note that antiblackness in social media is also present in the form of “race-neutral” algorithms that regularly suppress Black content creators and social media users. Several Tik Tok content creators noted that while their posts regarding Black Lives Matter were removed for violating the platform’s terms of service, racist comments on their profiles were protected by the site. Further, content creators reported that posts with “Black Lives Matter” tags were flagged for inappropriate content, while posts tagged “white supremacy” were left untouched (Ghaffary 2021). Antiblackness in digital socialization manifests in negative portrayals of Black people online, while simultaneously silencing Black counternarratives and resistance.

Endemic Antiblackness: Schools

The vestiges of chattel slavery continue to affect the lives of Black people in the United States—what Hartman describes as “the afterlife of slavery” (Hartman 2007, 6). The afterlife of slavery is understood as “skewed life chances, limited access to health [care] and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment” (Hartman 2007, 6). The presence of antiblackness in schools is one such manifestation of the afterlife of slavery. Warren and Coles (2020) identified three salient forms of assault Black children continue to experience in the afterlife of slavery: interpersonal assaults, curricular assaults, and environmental assaults.

Interpersonal assaults are present in the various interactions Black children have with their peers, teachers, and school staff. They may range from antiblack microaggressions to physical altercations. The arrest of a 10-year-old Black girl by Honowai police in January 2020 after making a drawing of another student that was bullying her is an example of the interpersonal assaults Black children face (Sutton and Chavez 2021). In this case, the girl’s mother was not even able to talk to her child before the police became involved. Interpersonal assaults affect Black children, and to a higher degree Black girls, regularly (Carter Andrews et al. 2019).

Curricular assaults manifest through dominant narratives of white supremacy that contribute to the minimization or erasure of Black culture, history, and contributions. Music classrooms overwhelmingly adhere to Eurocentric art ideals in content and instruction through ensembles that largely focus on white Western music, with European instruments and singing styles. These music practices are preserved through the repertoire that is chosen, instrumentation, and pedagogy (Hess 2021). While music education scholars have identified this as a manifestation of white supremacy (Hess 2021; Kajikawa 2019; Koza 2008), a theorization of antiblackness can build upon existing scholarship with increased specificity. Warren and Coles (2020) note that “the white supremacist power structure, as we know it in the U.S., cannot survive and thrive without the social construction of blackness as the thing to be most disdained” (384). Anti-black musical discourse acts as the fulcrum (Nakagawa 2012) that elevates musical practices steeped in white supremacy. Discourses surrounding music made by Black people have historically been framed by deficit thinking, such as the reductive discourse surrounding hip hop education (Crenshaw 1993; Robinson and Hendricks 2017). Furthermore, when Black artforms like hip hop and jazz are introduced in classrooms, the curriculum is largely void of the historical and political implications that shaped it in the first place (Hess 2018).

Environmental assaults in schools include limited access to resources and detrimental learning environments. Black students in urban schools regularly receive fewer opportunities to be in music classes and are given a lower quality education overall than the suburban schools that serve predominantly white populations (Salvador and Allegood 2014). In the U.S., schools in Black-serving urban communities receive less financial support per student than schools in more affluent suburban communities (DeLorenzo 2012; Elpus and Grisé 2019). A lack of financial support in high non-white, low socioeconomic status (SES) communities implies that Black students in low SES environments do not need or deserve a quality music program. This environmental assault may prevent students from continuing music and eventually becoming music educators (DeLorenzo and Silverman 2016). Only seven percent of music teacher licensure candidates in the U.S. are Black (Elpus 2015), highlighting a lack of representation in the field. Moreover, the vast majority of musicians in professional classical ensembles are white (DeLorenzo 2012), leading to a space that is virtually void of Black people. This compounds the hostile school-based environmental assaults on Black children in the music classroom.

Tension with the Neoliberal-Multicultural Imagination

In their second framing of BlackCrit, Dumas and ross (2016) emphasize that neoliberal forms of multiculturalism and diversity should be analyzed with wariness and scrutiny. The neoliberal push toward multiculturalism is a site for concern because the essentialized success of non-Black groups, such as the model minority myth (Iftikar and Museus 2018), implies that the barriers Black people face are of their own making—and if Black people just “try harder,” they will succeed. Dumas and ross (2016) contend that, “Black people continue to be the problem as the least assimilable to the multicultural imagination” (430). This aspect of neoliberal multiculturalism further reifies the antagonistic relationship between blackness and humanity, by putting blackness in opposition with other racially marginalized groups.

In the early part of the 1970s, calls for increased diversity were largely embraced in American music classrooms (Walter 2017). Attempts to incorporate multicultural music generally come in the form of students playing music from other cultures. Music publishers and various music organizations have created resources that promote multicultural music classrooms (Kang 2014), but many of these resources ultimately serve to uphold Eurocentric music ideals through a harmful form of decontextualized musical tourism (Hess 2015); and only benefit non-Black stakeholders in positions of power (teachers; musicians; music publishers). An example is the touristic consumption of Black music through the inclusion of hip hop in music classrooms, in which hip hop is used to attract students to music classes but where conversations about race and power are absent (Hess 2018), and the Eurocentric status quo in music class is maintained after the hip hop lesson or unit has concluded. This extractive practice acts as musical colonialism that functions to erase the contributions and histories of Black people. Much of the discourse surrounding the multicultural movement has failed to address race and racial tensions—leaving Eurocentric music practices unscathed (Bradley 2006). A lack of contextualization serves to erase the presence of blackness in curriculum and, inevitably, devalues blackness. The hegemony of Western European art music is maintained through the music selection, instrumentation, theory, and pedagogy in classrooms (Hess 2021).

Black cultural and musical traditions in the United States have largely been maintained through oral transmission throughout history (Hamlet 2011). Oral transmission includes melodies, rhythms, and inflections that cannot be adequately captured through Western music notation. Many of these Black American traditions also center the importance of lived experience and self-expression, such as the blues. When music teachers use Eurocentric epistemologies to interpret and disseminate Black American music, the rich context of the musical tradition is lost in translation. Multicultural music practices largely serve to entice children into classrooms through a “bait and switch” model (Hess 2015, 8).

Black Liberatory Fantasy

The third and final framing Dumas and ross (2016) offer is that of Black liberatory fantasy. They advance that BlackCrit should make space for Black liberatory fantasy since it is here that visions of a free society are possible and imagined: where the oppressive systems in which Black children exist are eradicated. Further, Dumas and ross (2016) contend that Black liberatory fantasy is not only a vision of a liberated world, but a vision of “the necessary chaos that must ensue” (431) for such change to occur.

Moments of Black liberatory fantasy provide escape and healing from the “spirit-murdering” (Williams 1987) to which Black bodies are subjected daily. Patricia Williams (1987) defines “spirit-murder” as a crime of racism, and “an offense so deeply painful and assaultive … victims of racism must prove that they did not distort the circumstances, misunderstand the intent, or even enjoy it” (129–30). Schools perpetuate spirit-murder through antiblack racism, which serves to dehumanize Black bodies (Love 2019). Hines and Wilmot (2018) contend that healing and opposition of spirit-murder must occur in schools since schools have been, and continue to be, sites of spirit-murdering.

I am compelled to imagine how music education may serve to nurture healing, an opposition to spirit-murdering, and revolution. In considering Gould et al.’s question of “how music education might matter’ (Gould et al. 2009), Hess (2021) emphasized the role music education may play in imagining a future of possibility. In exploring liberatory fantasies, oppressed voices have produced beautiful works of art that share facets of a collective suffering marginalized people can use for healing (Love 2019). And it is through liberatory practices that students can create music and art that allows them to construct meaning from their lived experience and imagine new worlds.

Afrofuturism

Afrofuturist artist and scholar Ytasha Womack describes Afrofuturism as “the intersection between black culture, technology, liberation, and the imagination, with some mysticism thrown in, too … It’s a way of bridging the future and the past and essentially helping to reimagine the experience of people of color” (Bakare 2014). White cultural critic Mark Dery coined the term “Afrofuturism” in a 1994 chapter entitled Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose in his book Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyber Culture, though Afrofuturist themes have been exemplified throughout history (Dery 1994). Lavender (2019) poignantly clarifies, “Dery asks the questions guiding these keen black minds and frames them with his brief introduction. Unquestionably, Afrofuturism’s critical vitality corresponds to these black scholars” (2). Afrofuturism has been adopted by activists, scholars, and artists, despite its link to science fiction. Afrofuturist themes in music can be traced back more than 70 years. Sun Ra (NPR Music 2014), the experimental jazz musician, infused his music with extraterrestrial influence in the 1950s.

Sun Ra Arkestra, Zoom https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H1ToFXHW5pg

Sun Ra Arkestra, Zoom https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H1ToFXHW5pg

In the 1970s, artists such as Jimi Hendrix, Earth Wind and Fire, and Parliament Funkadelic incorporated Afrofuturist ideals into rock and funk. Similarly, Michael Jackson and Janet Jackson (2009) and Missy Elliot (2009) exemplified Afrofuturism through their groundbreaking infusion of African American aesthetics and science fiction with popular music.

Michael Jackson and Janet Jackson, Scream https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0P4A1K4lXDo

Michael Jackson and Janet Jackson, Scream https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0P4A1K4lXDo

Missy Elliott, She’s a B**ch, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=opkRF3UZSJw

Missy Elliott, She’s a B**ch, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=opkRF3UZSJw

Afrofuturism has been used as a subversive practice that allows artists to challenge hegemonic narratives, reclaim memories, share intersectional stories, and center Black liberatory fantasies. These aspects of Afrofuturism run parallel to antiracist and other critical pedagogies, but Afrofuturism in this context uniquely considers an intersectional form of Black futurity. It is possible that Afrofuturism may provide insights into a possible BlackCrit praxis through musical action. I assert that the operationalization of Afrofuturism can challenge the hegemony of the Eurocentric music classroom in a way that benefits both Black and non-Black youth.

In the following sections I examine Janelle Monáe’s use of Afrofuturist themes and neo-funk sonic landscapes; and the ways in which these themes and sonic landscapes provide intersectional critical social commentary that center blackness and liberation.

Endemic Antiblackness

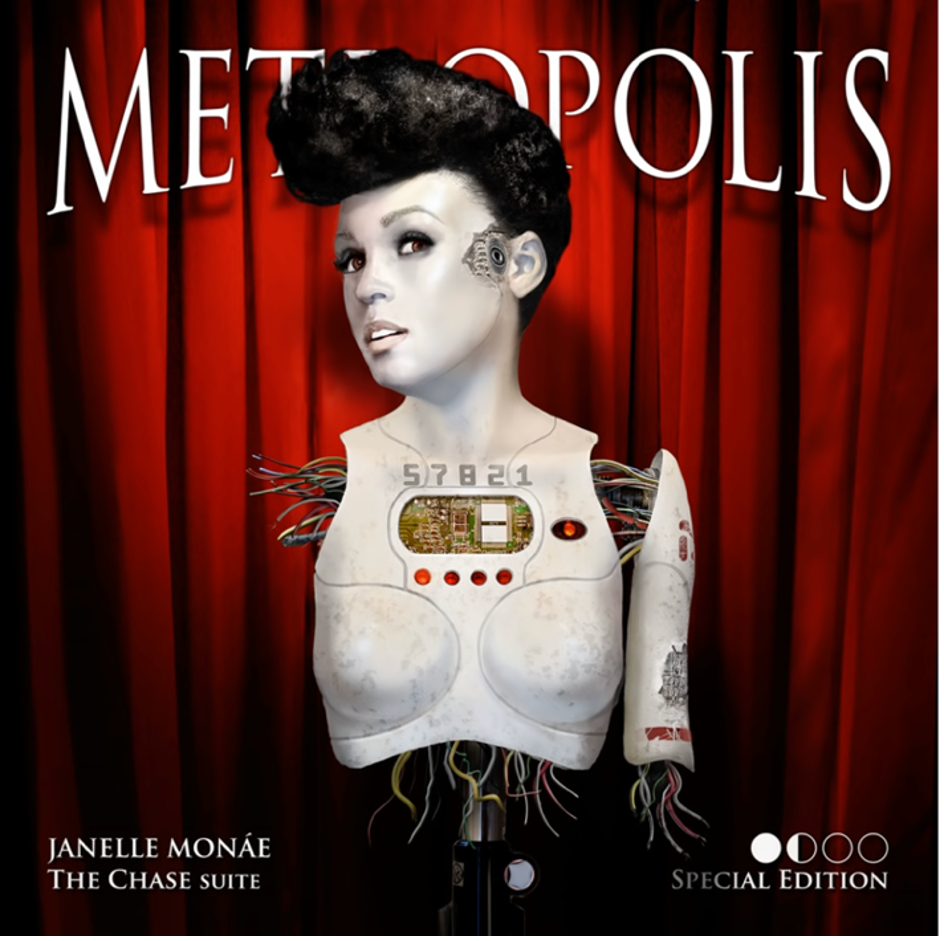

Janelle Monáe’s concept series began to emerge in 2007 with Metropolis: The Chase. Monáe plays the character of Cindi Mayweather, a fugitive android in a dystopian future, located in Star Core Metropolis, where androids are treated like property. Janelle Monáe clarifies their[3] android allegory in an interview with Evening Standard where they state that

I speak about androids because I think the android represents the new “other.” You can compare it to being a lesbian or being a gay man or being a black woman… What I want is for people who feel oppressed or feel like the “other” to connect with the music and to feel like, “She represents who I am.” (Evening Standard 2012)

Through the use of android allegories (see Dyer-Johnson 2021), Monáe’s dystopian future creates a parallel to the sub-human status to which Black bodies are currently subjected; but also features liberatory movements of the androids in Star Core Metropolis. Aja Romano, a writer for Vox.com, writes thus about liberation movements in Star Core Metropolis:

Liberation movements—android power, black power, queer pride, and freedom of artistic expression—have been suppressed but remain preserved through musical artifacts that surface as objects of quaint curiosity to the modern citizens of [Star Core] Metropolis. On the street (known as the “Wonderground”), however, they’ve survived through surreptitious community celebrations. Because of this, it’s always a big deal whenever music and dance interrupt the regimented life of Metropolis, and no one is more of an agitator than Cindi Mayweather. (Romano 2018)

The antiblack socialization that occurs through media and schooling takes a new form in Monáe’s universe. The androids, who have non-human status, are subjugated by an organization called The Great Divide; and there is a complete disregard for androids’ wellbeing or autonomy. The constant assault toward androids resembles the dehumanizing forms of antiblack assault experienced by Black people. Monáe’s representation of oppression communicates another important point: the need for true liberation to be intersectional—“android power, black power, queer pride” (Romano 2018).

Resisting the Neoliberal-Multicultural Imagination

In his foundational chapter, Mark Dery (1994) asks “can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, imagine possible futures?” (180). Janelle Monáe answers this question through their use of time travel in music videos, concept albums, and emotion pictures; exploring the “afterlife of slavery” (Hartman 2007) in which oppressors erase the memories of trouble-making androids labeled “dirty computers.” Afrofuturism centers the lived experiences of Black people and uses the past to inform the present and future. The use of time travel allows Monáe to explore “past-future visions,” (Nelson 2000) reimagining antiblackness through android allegories and resistance as software glitches; reclaiming memories and building underground coalitions with the goal of escaping oppressive existences. This aspect of Monáe’s work exemplifies Dumas and ross’ framing of resisting the neoliberal-multicultural imagination (2016). It pushes against the notions of seemingly natural hierarchies; and the antagonistic relationship between the android and the human. Monáe’s use of time travel allows them to navigate linear historiographies to find and make visible counternarratives throughout history; and, through these narratives, assert the personhood of the androids.

Janelle Monáe, March of the Wolfmasters https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3XvpQbOtzIU

Janelle Monáe, March of the Wolfmasters https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3XvpQbOtzIU

Black Liberatory Fantasy

Metropolis: The Chase (2007) is an exercise in using an Afrofuturist epistemology to understand society’s relationship with blackness and oppression. Monáe explores this relationship over the next decade in their oeuvre with works such as The Electric Lady (2013) and ArchAndroid (2010) that further explore the dystopian world. The single Tightrope in the ArchAndroid (2010) album highlights the importance of resistance in the face of oppression. Monáe’s music video showcases dancing as a subversive act; and the spaces that provide asylum to the cyborgs.

Janelle Monáe (feat. Big Boi), Tightrope https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pwnefUaKCbc

Janelle Monáe (feat. Big Boi), Tightrope https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pwnefUaKCbc

In 2018, Janelle Monáe released an album and feature-length music video sharing the same name, Dirty Computer (2018). Monáe’s work in Dirty Computer further operationalizes BlackCrit’s framing of Black liberatory fantasy. Critic Russell Dean Stone writes that

Thematically, Dirty Computer is a manifesto about love, black excellence, girl power, freedom, respect, otherness, sex-positivity, and queer-friendly utopianism. Monáe has conceived an album for the marginalized, fueled by love that doesn’t see difference as a flaw but instead marvels at the beauty of imperfection. (Stone 2018)

Janelle Monáe, PYNK https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PaYvlVR_BEc

Janelle Monáe, PYNK https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PaYvlVR_BEc

Fear exists that dancing may lead to forbidden magical practices. Resistance begins through music and dance in Star Core Metropolis. There is fear that dancing may become marching, and pandemonium may ensue. Similar fears were held by slave owners that prevented enslaved Africans from musicking and dancing; this fear of revolt caused slaveowners to make such activities illegal. This same fear exists in classrooms, where even small forms of non-compliance from Black children are met with zero-tolerance policies (Hines-Datiri and Carter Andrews 2020). Monáe uses their audiovisual productions as a source of refuge, healing, and as a rallying call. What might it look like if the music education field answered that call? What is an Afrofuturist music education; and why an Afrofuturist music classroom?

Why an Afrofuturist Music Classroom?

Gould (2007) has argued that “unexamined traditional liberal practices may serve to reinscribe colonial narratives” (229). Ensemble-style Eurocentric music making in music classrooms is one such manifestation of these often-unexamined practices. A direct challenge to this paradigm may be found through informal music learning practices, and the inclusion of popular music, in an attempt to subvert the traditional ensemble paradigm. However, the inclusion of pop culture and science fiction in the classroom may function as a site of antiblack racism if left unexamined, due to its insidious nature. This antiblack racism may manifest in a number of ways without the proper framing of antiblackness, such as negative stereotypes and erasure (Dumas and ross 2016). I contend that critical pedagogy is insufficient, without the specificity of antiblackness.

An Afrofuturist epistemology in the music classroom may prevent antiblack rhetoric that exists in classrooms and in media; but pop culture and science fiction require further examination before introducing into the classroom. Robert Schwartz (2019) has written about whiteness in popular and nerd culture (e.g., science fiction), noting that Black people are largely absent. Recently, media companies such as Disney and Amazon have, intentionally or otherwise, diversified the “canon” of popular and nerd culture through the inclusion of Black protagonists and characters in The Little Mermaid (2023) and The Lord of the Rings: Rings of Power (2022), respectively. The addition of Black actors to these stories that have typically been portrayed solely by white characters has been met with overt anger and racism that reverberated through the internet for some time (Romano 2022). I assert that such strong responses exist because the centrality of whiteness in popular and nerd culture is maintained through its antagonistic relationship with blackness. Further, I believe that merely adding Black actors to Eurocentric fantasy worlds, such as the ones found in The Little Mermaid and The Lord of the Rings, does nothing to create meaningful change.

I contend that Afrofuturist approaches in the music classroom may serve as means by which students increase the critical awareness that is essential in navigating potential sites of antiblack violence. Further, an Afrofuturist approach to music practices may serve to create sites of Black interpersonal, curricular, and environmental affirmation with effects that go beyond the classroom; facilitating the development of several foundations and skills for Black students and their peers, both Black and non-Black. First, an Afrofuturist classroom can cultivate a foundation of Critical Race Theory and BlackCrit. Students would come to know race as a social construction and come to terms with its ubiquity. Further, students can learn about concepts such as interest convergence, intersectionality, and essentialism. Students would learn this through discussions of the systems that form popular culture; and the ways in which some voices are silenced while others are amplified. Secondly, an Afrofuturist music classroom can be a site where students come to terms with racial domination and oppression. This process would happen through environmental and curricular affirmations in the classroom that help Black students navigate internalized oppression and help all students realize their own power, while cultivating anti-racist epistemologies. Finally, an Afrofuturist music classroom may function in healing and comforting students while they face difficult truths. Indigenous scholar Valerie Shirley (2017) has conceptualized such practices as “cultivating the heart” (164). Shirley noted that there is potential for trauma and harm when students are actively engaged in pedagogy that decolonizes aspects of their learning. Shirley speaks of “cultivating the heart” of students as they navigate these difficulties to lessen this potential for trauma and harm. In the following sections I explore how an Afrofuturist classroom may serve to counteract the antiblack sites of violence that exist within schools, while “cultivating the heart” through interpersonal, curricular, and environmental affirmations.

Interpersonal Affirmations

Janelle Monáe’s artistic universe serves as an allegory that warns that resistance is far from simple. Any android that deviates from the normative center is said to have faulty coding that necessitates reprogramming. This theme is made evermore salient in Monáe’s opening dialogue in Dirty Computer (2018) where they state,

They started calling us computers. People began vanishing, and the cleaning began. You were dirty if you looked different. You were dirty if you refused to live the way they dictated. You were dirty if you showed any form of opposition at all. And if you were dirty, it was only a matter of time…

Janelle Monáe, Dirty Computer https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jdH2Sy-BlNE

Janelle Monáe, Dirty Computer https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jdH2Sy-BlNE

The only true escape from this incessant control comes in the form of the Wonderground, a secret place of resistance. In his book on Janelle Monáe’s use of Afrofuturist aesthetic, Hassler-Forest (2022) writes thus about the centrality of race and resistance in Monáe’s works; and how they disrupt the binary of whiteness as light and innocent, and blackness as dark and evil:

For Afrofuturists like Monáe, the fantasy helps us face reality in order to transform it. Her narratives, characters, and emotions stage an unavoidable confrontation with the racial organization of our social order. In other words, one of Afrofuturism’s key functions is to short-circuit fantastic fiction’s binary separating the myth of white innocence from the racialized positioning of the Dark other as an antagonist. (16)

Monáe’s use of Afrofuturist aesthetics and the liberties granted through time travel create multiple opportunities for interpersonal affirmations to occur that may counteract some of the effects of antiblack interpersonal violence. Time travel allows Monáe’s characters to escape linear views of historiography and to de- and re-construct facets of their lives. This same notion of time travel may be useful in music classrooms. Music classrooms can serve as spaces that allow children and youth to make meaning of their lives and their futures. A student may choose to construct music celebrating a utopian future, and the necessary work that must occur to reach it, in an Afrofuturist classroom. A student may also choose to explore a dystopian future with facets of oppression and harm that reflect their current lives. Engaging in such an exercise may help students to imagine and support one another through the realization of the endemic nature of antiblackness; while also dreaming of liberation and potentially experiencing catharsis. An Afrofuturist music classroom would allow students to explore these futures in a space where harm can be contemplated upon, and joy can still manifest. Similarly, traveling through the past with an Afrofuturist framework would allow students to de- and re-construct spaces where Black and other oppressed people were historically excluded. Exploring music through past-future visions would allow students and teachers to reclaim historically white spaces by rediscovering the Black people that have always been present; or by reimagining what these spaces may have looked like. Intentional subversion of white hegemonic narratives and critical reflection in the music classroom can help students name oppression, make meaning of transgressions made against them, and cultivate heart.

Monáe demonstrates the importance of interpersonal affirmations through the coalitions they build and the way they care for the other fugitive androids. Many scenes in their feature-length music videos center marginalized bodies loving and protecting one another. The androids preserve culture and heart through fugitive spaces in the Wonderground. Monáe’s mastery of coalition building has powerful implications for the music classroom. An Afrofuturist music classroom may allow space for students to show love and support for one another. This same space, while healing, can further serve as a site for action. Teachers will need to cultivate spaces that show students the transformational power of interpersonal connections. Opportunities may potentially exist in past-future visions, where students can reimagine the various community-oriented practices in cultures influenced by the African diaspora. Further, teachers should encourage students to engage in communal forms of musicking that allow people from a variety of experiential backgrounds to convene.

Curricular Affirmations

Janelle Monáe’s Metropolis concept album pays homage to Fritz Lang’s 1927 science fiction film sharing the same name. Vox writer Aja Romano (2018) writes that,

From her first reference to Metropolis, the cold, dystopian, slave droid-powered city that looms over each of her albums, Monáe has built her discography through sci-fi [science fiction] tropes codified by 20th-century white male writers. In the process, as great women of sci-fi have done before her, she’s mapped those narratives onto her own identity, claiming them for “androids” like herself (par. 3)

Monáe takes Lang’s core android theme and art deco style and infuses it with their own identity and aesthetic. Monáe explains, in an interview with New York Public Radio, that Lang’s film inspired the album because

it mirrors the constant struggle between the haves and the have-nots that’s still going on in the present. I have a very imaginative mind, and I just went further with it. But Metropolis is here, it’s universal. (Andersen 2016, par. 2)

Monáe’s ability to deconstruct various works and styles allows them to continuously assert their identity in a variety of spaces. I contend that an Afrofuturist music classroom creates an affirming curricular environment where students are exposed to multiple epistemologies and are encouraged to acknowledge alternate ways of seeing the world and problem-solving.

An Afrofuturist curriculum would necessitate space for counter-hegemonic thinking. The centricity of whiteness in curriculum must be challenged for students to actively engage in counter-hegemonic thinking. An Afrofuturist epistemology would destabilize the centrality of whiteness by allowing students to compare, contrast, deconstruct, and reconstruct multiple ways of knowing the world; through multidisciplinary means.

For example, an Afrofuturist curriculum in the music classroom could introduce students to foundational artists (not just musicians) in the movement to disrupt the typical Eurocentric music classroom in multiple ways. Students could learn about the meaning behind Sun Ra’s music and messages; be introduced to Jean-Michel Basquiat’s art; and make connections to past and current events. Allowing students to extensively engage in Afrofuturist epistemologies through curriculum may potentially serve to destabilize the foundation of white supremacy, which is built upon antiblack racism.

Environmental Affirmations

One thing is certain throughout all of Monáe’s music and visuals: they are in control of their environment. Monáe made an intentional choice to use Fritz Lang’s white science fiction and make it Black. Monáe creates a dystopian future and creates a fugitive space within it that provides safety from an oppressive environment. Aja Romano (2018) writes:

In Star Core Metropolis, liberation movements—android power, black power, queer pride, and freedom of artistic expression—have been suppressed but remain preserved through musical artifacts that surface as objects of quaint curiosity to the modern citizens of Metropolis. On the street (known as the “Wonderground”), however, they’ve survived through surreptitious community celebrations. (par. 2)

Monáe’s control of their environment may serve as a blueprint for the Afrofuturist classroom. An Afrofuturist music classroom can only exist in an environment that affirms Black youth. These sites of affirmation need to be actively constructed by teachers and students, to prevent harm and promote liberation. Teachers need to be responsible for curating spaces, with their students, that are tangibly different from traditional music learning spaces that situate the teacher as the ultimate authority and knower. Opportunities may potentially exist in new seating layouts that allow students to work separately or collaborate on projects. Teachers should also be intentional with the decor and representation of artists in their space to disrupt the notion that certain people or musics are more valuable than others. Further, teachers should encourage students to engage in multiple forms of musicking that destabilize the supremacy of Western European musical ensembles.

Vignette of an Afrofuturist Lesson

The students in Mx[4]. Ra’s class sprawl across the room in small groups. Various thought-webs can be seen on boards and on posters. The first group has something written down about how disorganized the cafeteria is after lunch; another group talks about all the food waste that occurs during lunch. At the other end of the room there is a huge circle around the sentence “Smelly snails around the lake?” The students are currently in the “Past-Future Visions Unit” in their Afrofuturism unit on activism. Mx. Ra has been teaching the class about Haitian mizik angaje,[5] and how politically and socially engaged music can create change without the need for financial capital. Mx. Ra chose mizik angagje, literally meaning “engaged music,” to highlight instances where material poverty was remedied through community cultural wealth in Haiti. Mx. Ra reminds the students that Haiti was the first country to ban slavery permanently in 1793 and was seen as a threat. The teacher notes that U.S. President Thomas Jefferson placed Haiti in a diplomatic and economic chokehold, forcing the Haitian people to be resourceful in their solutions.

Mx. Ra directs students to choose socially engaged music and to reimagine it through their own lives. The classroom space is full of photos highlighting the role music has played in engaging communities, ranging from the music that propelled the Civil Rights movement, to underground Iranian punk music scenes, to efforts like the Live Aid benefit in 1985. There are various guidelines in place: 1) Students are asked to focus on school and community aspects they would like to see change; 2) Students need to develop some actionable steps that can lead to the change they would like to see; 3) Students need to provide a reflection on how this proposed plan of action benefits, or potentially harms, various marginalized groups; and 4) Students need to provide a reflection of the different musical influences used in their projects. This reflection will include contextualization of the music style and a rationalization of its use. This project is an iterative one, with multiple rounds where students tweak and alter elements of their work, before presenting their composed music to their intended audiences.

Coda

Through their use of past-future visions, Janelle Monáe’s work transforms the afterlife of slavery into a dystopian future that parallels the assault many Black folks regularly face. These concept albums and emotion pictures are exercises in fugitivity that produce beautiful art to enjoy but, more importantly, helps those in similar struggles explore their liberatory fantasies. Further, the healing that takes place is not just for listeners; Monáe is able to free and liberate pieces of their own identity. Most importantly, Janelle Monáe is asking everyone to get with the funk and make some noise.

In its current state, music education functions to uphold white supremacy (Hess 2015, 2021; Kajikawa 2019). It is upheld through Eurocentric music practices and is further elevated through anti-black racism. Black children experience racially motivated assaults in schools, in the home, and through social and digital media (Dumas 2016). Monáe’s music speaks about the importance of being seen, heard, loved, and cared for. I believe that music classrooms can be spaces that allow the Black imagination to be free. I believe that music classrooms can be a space where Black children can feel seen, loved, and cared for. So, I ask a new question: How might music education matter to Black children?

About the Author

Lorenzo Sánchez-Gatt (He/They) is currently a PhD candidate at Michigan State University. Lorenzo earned their Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in music education from Southeastern University and Florida State University, respectively. Prior to their studies at Michigan State University, Lorenzo held a position teaching elementary and middle school orchestra, guitar, and music appreciation in central Florida. Lorenzo’s interests as a scholar-activist include anti-oppressive education, centering Black and Latiné experiences, Afrofuturism, and Critical Race Theory in music education. Lorenzo’s interests were shaped through their experiences navigating being a student, performer, and educator as a queer Afro-Latiné person. Lorenzo has been selected to present papers and workshops at the American Educational Research Association, National Association for Music Education, Critical Race Studies in Education Association, Big Ten Academic Alliance, MayDay Group, and various state conferences. Lorenzo’s scholarship and work span a variety of topics relating to social and epistemic justice.

References

Adams-Bass, Valerie, Howard Stevenson, and Diana Kotzin. 2014. Measuring the meaning of black media stereotypes and their relationship to the racial Identity, black history knowledge, and racial socialization of African American youth. Journal of Black Studies, 45 (5): 367–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934714530396

Andersen, Kurt. 2016. Janelle Monáe, back from the future. Studio 360. WNYC. https://www.wnyc.org/story/janelle-monae-back-from-future

Bakare, Lanre. 2014. Afrofuturism takes flight: From Sun Ra to Janelle Monáe. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2014/jul/24/space-is-the-place-flying-lotus-janelle-monae-afrofuturism

Bowleg, Lisa, Cheriko Boone, Sidney Holt, Ana Marie del Río-González, and Mary Mbaba. 2022. Beyond “heartfelt condolences”: A critical take on mainstream psychology’s responses to anti-Black police brutality. American Psychologist 77 (3): 362.

Bradley, Deborah. 2006. Music education, multiculturalism, and anti-racism—Can we talk? Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 5 (2): 2–30. https://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Bradley5_2.pdf

Busey, Christopher, and Tianna Dowie-Chin. 2021. The making of global Black anti-citizen/citizenship: Situating BlackCrit in global citizenship research and theory. Theory & Research in Social Education 49 (2): 153–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2020.1869632

Butkowski, Chelsea, Lee Humphreys, and Utkarsh Mall. 2022. Computing colorism: Skin tone in online retail imagery. Visual Communication. https://doi.org/10.1177/14703572221077444

Carter Andrews, Dorinda, Tashal Brown, Eliana Castro, and Effat Id-Deen. 2019. The impossibility of being ‘perfect and white’: Black girls’ racialized and gendered schooling experiences. American Educational Research Journal 56 (6): 2531–72.

Coles, Justin, Esther Ohito, Keisha Green, and Jamila Lyiscott. 2021. Fugitivity and abolition in educational research and practice: An offering. Equity & Excellence in Education 54 (2): 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2021.1972595

Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1993. Beyond racism and misogyny: Black feminism and 2 Live Crew. In Feminist social thought: A reader, edited by Diana Tietjens Meyers, 245–63. Routledge.

DeLorenzo, Lisa. 2012. Missing faces from the orchestra: An issue of social justice? Music Educators Journal 98 (4), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432112443263

DeLorenzo, Lisa, and Marissa Silverman. 2016. From the margins: The underrepresentation of Black and Latino students/teachers in music education. Visions of Research in Music Education 27 (3): 1–40.

Dery, Mark, ed. 1994. Flame wars: The discourse of cyberculture. Duke University Press.

Dixson, Adrienne D., and Celia K. Rousseau. 2005. And we are still not saved: Critical race theory in education ten years later. Race Ethnicity and Education 8 (1): 7–27. https://doi-org.10.1080/1361332052000340971

Dumas, Michael J. 2016. Against the dark: Antiblackness in education policy and discourse. Theory Into Practice 55 (1): 11–9. https://doi.org.10.1080/00405841.2016.1116852

Dumas, Michael J., and kihana miraya ross. 2016. “Be real black for me”: Imagining BlackCrit in education. Urban Education 51 (4): 415–42. https://doi.org.10.1177/0042085916628611

Dyer-Johnson, Omara Samirah. 2021. Imagining a better world: Black futurity in contemporary Afrofuturism and speculative fiction. PhD diss., University of Nottingham.

Elliott, Missy. 2009. She’s a B**ch. Youtube, uploaded by Missy Elliott. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=opkRF3UZSJw

Elpus, Kenneth. 2015. Music teacher licensure candidates in the United States: A demographic profile and analysis of licensure examination scores. Journal of Research in Music Education 63 (3): 314–35.

Elpus, Kenneth, and Adam Grisé. 2019. Music booster groups: Alleviating or exacerbating funding inequality in American public school music education? Journal of Research in Music Education 67 (1): 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429418812433

Evening Standard. 2012. RnB sensation Janelle Monáe is here because we need her. https://www.standard.co.uk/lifestyle/rnb-sensation-janelle-monae-is-here-because-we-need-her-6418158.html

Ghaffary, Shirin. 2021. How TikTok’s hate speech detection tool set off a debate about racial bias on the app. Vox. https://www.vox.com/recode/2021/7/7/22566017/tiktok-black-creators-ziggi-tyler-debate-about-black-lives-matter-racial-bias-social-media

Gould, Elizabeth. 2007. Social justice in music education: The Problematic of democracy. Music Education Research 9 (2): 229–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613800701384359

Gould, Elizabeth, June Countryman, Charlene Morton, and Leslie S. Rose, eds. 2009. Exploring social justice: How music education might matter. Canadian Music Educators’ Association.

Hamlet, Janice D. 2011. Word! The African American oral tradition and its rhetorical impact on American popular culture. Black History Bulletin 74 (1): 27–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24759732

Hartman, Saidaya V. 2007. Lose your mother: A journey along the Atlantic slave route. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Hassler-Forest, Dan. 2022. Janelle Monáe’s queer afrofuturism: Defying every label. Rutgers University Press. https://doi.org/10.36019/9781978826724

Hess, Juliet. 2015. Decolonizing music education: Moving beyond tokenism. International Journal of Music Education 33 (3): 336–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761415581283

Hess, Juliet 2018. Hip hop and music education: Where is race? Journal of Popular Music Education 2 (1): 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1386/jpme.2.1-2.7_1

Hess, Juliet 2021. Becoming an anti-racist music educator: Resisting whiteness in music education. Music Educators Journal 107 (4): 14–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/00274321211004695

Hines, Dorothy E., and Jennifer M. Wilmot. 2018. From spirit-murdering to spirit-healing: Addressing anti-black aggressions and the inhumane discipline of Black children. Multicultural Perspectives 20 (2): 62–69.

Hines-Datiri, Dorothy, and Dorinda J. Carter Andrews. 2020. The effects of zero tolerance policies on Black girls: Using critical race feminism and figured worlds to examine school discipline. Urban Education 55 (10): 1419–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085917690204

Ibrahim, Shamira. 2022. Africans in Ukraine: Stories of war, anti-blackness & white supremacy. Refinery29. https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2022/03/10891492/african-students-ukraine-racism

Iftikar, Jon S., and Samuel D. Museus. 2018. On the utility of Asian critical (AsianCrit) theory in the field of education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 31 (10): 935–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2018.1522008

Jackson, Michael, and Janet Jackson. 2008. Scream. YouTube, uploaded by michaeljacksonVEVO. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0P4A1K4lXDo

Kajikawa, Loren. 2019. The possessive investment in classical music: In Seeing Race Again, edited by Kimberlé Crenshaw, Luke Charles Harris, Daniel Martinez HoSang, and George Lipsitz, 155–74. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvcwp0hd.12

Kang, Sangmi. 2014. The history of multicultural music education and its prospects. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education 34 (2): 21–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/8755123314548044

Koza, Julia Eklund. 2008. Listening for whiteness: Hearing racial politics in undergraduate school music.” Philosophy of Music Education Review 16 (2): 145–55.

Ladson-Billings, Gloria, and William Tate. 1995. Toward a critical race theory of education. Teachers College Record 97 (1): 47–68. https://doi-org/10.1177/016146819509700104

Lavender, Isiah. 2019. Afrofuturism rising: The literary prehistory of a movement. https://doi.org/10.26818/9780814214138

Lott, Eric. 2013. Love and theft: Blackface minstrelsy and the American working class. Oxford University Press.

Love, Bettina. 2019. We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

Marshall, Rob, director. 2023. The Little Mermaid. Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures.

Monáe, Janelle. 2007. Metropolis: The Chase Suite. Bad Boy Records.

Monáe, Janelle. 2010. The ArchAndroid. Wondaland Arts Society; Bad Boy; Atlantic.

Monáe, Janelle. 2013. The Electric Lady. Wondaland Arts Society; Bad Boy; Atlantic.

Monáe, Janelle. 2018. Dirty Computer. Wondaland; Bad Boy; Atlantic.

Nakagawa, Scot. 2012. Blackness is the fulcrum. Race Files. http://www.racefiles.com/2012/05/04/blackness-is-the-fulcrum/

Nelson, Alondra. 2000. Afrofuturism: Past-future visions. Color Lines 3 (1): 34–47.

NPR Music. 2014. Sun Ra Arkestra: NPR Music Tiny Desk Concert. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H1ToFXHW5pg

Preston, Ashley. 2021. Taking on tech: Social media’s anti-blackness and algorithmic aggression in the absence of accountability. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestheculture/2021/08/09/taking-on-tech-social-medias-anti-blackness-and-algorithmic-aggression-in-the-absence-of-accountability/?sh=7d5fd3f93c79

Prot, Sara, Craig Anderson, Douglas Gentile, Wayne Warburton, Muniba Saleem, Christopher Groves, and Stephanie Brown. 2015. Media as agents of socialization. In Handbook of socialization, edited by Joan E. Grusec, and Paul D. Hastings, 276–300. 2nd ed. The Guildford Press.

Robinson, Deejay, and Karin Hendricks. 2017. Black keys on a white piano: A negro narrative of double-consciousness in American music education. In Marginalized voices in music education, edited by Brent C. Talbot, 28–47. Routledge.

Romano, Aja. 2018. Beyond Dirty Computer: Janelle Monáe’s science fiction universe. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2018/5/16/17318242/janelle-monae-science-fiction-influences-afrofuturism

Romano, Aja. 2022. The racist backlash over increased diversity in The Little Mermaid and Lord of the Rings, explained. Vox. https://www.vox.com/culture/23357114/the-little-mermaid-racist-backlash-lotr-rings-of-power-diversity-controversy

Salvador, Karen, and Kristen Allegood. 2014. Access to music education with regard to race in two urban areas. Arts Education Policy Review 115 (3): 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2014.914389

Schwartz, Robert. 2019. Decolonizing the imagination: Teaching about race using Afrofuturism and critical race theory. Curriculum unit. Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute.

Shirley, Valerie. 2017. Indigenous social justice pedagogy: Teaching into the risks and cultivating the heart. Critical Questions in Education 8 (2): 163–77.

Solórzano, Daniel, and Dolores Delgado Bernal. 2001. Examining transformational resistance through a critical race and Lat-Crit theory framework: Chicana and Chicano students in an urban context. Urban Education 36: 308–42.

Stone, Russell. 2018. Janelle Monáe builds an Afrofuturist utopia on “Dirty Computer.” Highsnobiety. https://www.highsnobiety.com/p/janelle-monae-dirty-computer-review

Sutton, Joe, and Nicole Chavez. 2021. A black girl was arrested at school in Hawaii over a drawing that upset a parent. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2021/10/20/us/hawaii-black-girl-arrested-drawing-aclu/index.html

Walter, Jennifer. 2017. Global perspectives: Making the shift from multiculturalism to culturally responsive teaching. General Music Today 31 (2): 24–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1048371317720262

Warren, Chezare, and Coles Justin. 2020. Trading spaces: Antiblackness and reflections on black education futures. Equity & Excellence in Education 53 (3): 382–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2020.1764882

Williams, Patricia. 1987. Spirit-murdering the messenger: The discourse of fingerpointing as the law’s response to racism. University of Miami Law Review 42: 127–57.

[1] Dumas (2016) offers a compelling rationale for the lower-case spelling of blackness, antiblackness, white, and whiteness stating: “white is not capitalized in my work because it is nothing but a social construct, and does not describe a group with a sense of common experiences or kinship outside of acts of colonization and terror. Thus, white is employed almost solely as a negation of others—it is, as David Roediger (1994) insisted, nothing but false and oppressive. Thus, although European or French are rightly capitalized, I see no reason to capitalize white. Similarly, I write blackness and antiblackness in lower-case, because they refer not to Black people per se, but to a social construction of racial meaning, much as whiteness does. Finally, I sometimes reference the Black, which refers to the presence of Black bodies, or more precisely, the imagination of the significance of Black bodies in a certain place” (13).

[2] kihana miraya ross intentionally writes their name in lower-case.

[3] Monaé clarifies in the 28th Critics’ Choice Awards that they are a non-binary person whose preferred pronouns are “she/her, they/them, and free-ass motherfucker.” My use of pronouns in this article reflects this choice.

[4] Mx is a gender-neutral honorific.

[5] Mizik angaje is a socially and politically engaged musical style originating in Haiti.