Control, Constraint, Convergence:

Examining Our Roles as Generalist Teacher Music Educators

DANIELLE SIREK

University of Windsor, Ontario, Canada

TERRY SEFTON

University of Windsor, Ontario, Canada

July 2018

Published in Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education ACT 17 (2): 50–70. [pdf]

doi:10.22176/act17.2.50

This research explores the effects of institutional constraints on instructional practices in a preservice generalist teacher music education program in Ontario, Canada. Using Institutional Ethnography and document analysis of active texts, we, an adjunct and tenured professor, use our own experiences to elucidate the multiple points of control and constraint in which teacher education instructors operate. We examine the ways in which “official” documents, such as course outlines, activate institutional expectations and relations of power, and promote standardization (convergence). We explore factors that influence our curricular choices, pedagogical strategies, and occasional acts of resistance; and how these impact differently tenured and adjunct faculty. The paper includes an introduction to the Action Research project that sparked this inquiry, in which we are investigating generalist teacher confidence and engagement with teaching music in the elementary classroom.

Keywords: preservice teacher education, music education, Institutional Ethnography, adjunct faculty

We are teaching colleagues at a mid-sized university in Ontario, Canada, where we teach in a Faculty of Education. We have both taught Bachelor of Education music methodology[1] courses for generalist (non-specialist) teachers and we have both encountered student resistance to course content. In 2016, we began a funded research project to explore factors that influence generalist teacher confidence and engagement with teaching music in the elementary classroom. Our hope was to improve course content as well as our own teaching practice in music methodology classes. The project arose from our shared belief that relevancy and engagement in our teacher education classes would be more likely if we had a deeper understanding of our students. We framed the inquiry as Action Research.

Over several months, while we completed classroom observations and ran focus groups for our project, we would meet and talk frequently. Our conversations sometimes wandered into our feelings about recent demands from faculty administrators. At the time, our program was undergoing re-accreditation. Accreditation is a provincial government process that occurs every 5 to 7 years, during which outside “experts” come to assess faculty compliance with provincially regulated teacher education requirements. In anticipation of this visit, our administrators went into a fevered house cleaning which precipitated a flurry of emails and directives to faculty members, both adjunct and tenured. These requests, often expressed as demands, included decorating and organizing classrooms, interviews with panel members, and providing course documents that aligned with standardized templates. As we discussed our reactions to the most recent communications from administration, we noted that Danielle’s responses were very different than Terry’s. In our discussions, it became clear that our contrasting approaches were due to more than a difference in personality or opinion; in brief, they could be attributed to the difference in status and job security. We started to see our research project as enmeshed in layers of institutional expectations and constraints, and how these converged to produce effects on teaching and learning—factors that we had not previously accounted for. This led us into a parallel inquiry, and required a different methodological lens.

In this paper, we draw from our different perspectives as adjunct professor, Danielle, and tenured professor, Terry. At our institution, an adjunct professor is called a “sessional instructor”: someone who works contract to contract without guarantee of future work from one semester to the next. They usually receive no benefits or pension, and are not often included in Faculty governance. While some researchers are skeptical of the exploitation of adjunct faculty (see Brennan and Magness 2016), much writing has recently pointed to extremely negative effects of adjunctification, both for institutions and the adjuncts themselves; for example, adjunctification as a means of securing a disciplined labor force (Ovetz 2015), relative deprivation of adjunct faculty (Feldman and Turnley 2004); increased need of adjunct support by tenured faculty (Fagan-Wilen, Springer, Ambrosino and White 2004), and adjuncts’ desires for full-time positions (Field and Jones 2016). Tenured or tenure-track professors occupy not only a different status but must undertake different roles and are contractually required to perform different functions. These roles include service (sitting on committees, including hiring committees and Senate[2], graduate student supervision, and research. We discuss how our standpoints framed our choices to conform to or to resist administrative demands, and we examine how tensions of institutional mandates, academic freedom, and job precarity collide in higher education.

Drawing from Institutional Ethnography (Smith 1987, 1990a, 1990b, 1999, 2005), and conceptualizations of fields of cultural production (Bourdieu 1992/1996, Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992), we use our lived experiences to identify the multiple limitations within which teacher education instructors operate. We examine each of these aspects in our work: control, constraint, and convergence. We explore how systems exert control over actors; and actors over other actors—in a dynamic relation of power. We explore constraint of action—ways in which those with less power feel constrained in how they respond to directives from administration, constraint as an intended consequence of administrative directives, and standardization as a motivation for constraint. And we explore convergence—pressures exerted on faculty resulting in less risk-taking and more conformity, which leads to preservice teachers being schooled in low-risk approaches to teaching and planning. Preservice teachers then take this model into the schools, perpetuating a conservative ethos of pedagogy that is monocultural, and delivering a curriculum predicated on measurable learning outcomes. Like converging weather-fronts; this produces a perfect storm that shuts down avenues of exploration and creation.

Methods

Institutional Ethnography

Institutional Ethnography examines social organizations and relations of power. It refers to “the investigation of empirical linkages among local settings of everyday life, organizations, and translocal processes of administration and governance” (DeVault and McCoy 2006, 15). Analyses are carried out through a variety of research strategies and types of “data” that trace chains of human activity and individual agency or subjectivity as revealed by texts and textual practices that prompt processes of work and that are embedded in structures of power and oppression. Institutional Ethnography grew out of the work of Dorothy Smith (1987, 1990a, 1990b, 1999) who developed a feminist theory of sociology and the concept of the relations of ruling. Smith (2005) proposed an approach to social investigation that encourages people to uncover how the “local actualities” of their “everyday/everynight” lives reveal the workings of institutions, regimes of power, and relations of ruling. While Institutional Ethnography resembles research traditions of ethnography and methodologies such as case studies, it differs in its inception of the “problematic,” its focus on being written “from people’s standpoint,” and its “objects of investigation”:

[Institutional] Ethnography may start by exploring the experience of those directly involved in the institutional setting, but they are not the objects of investigation. It is the aspects of the institutions relevant to the people’s experience, not the people themselves, that constitute the object of inquiry. (2005, 38)

Furthermore, its ultimate goal is not to create a theory or to generalize, but to travel “deeper into the institutional relations in which people’s everyday lives are embedded” (38).

Often, people don’t set out to do institutional ethnography. They fall into it. In our case, we experienced a pivot in our discussions of teaching and research. Within the frame of Action Research, we were using narrative inquiry and ethnography to explore the stories of students and we were collecting data from focus group interviews and observations. But there was an incoherence between us and our project: a current was running underneath the surface that rendered our individual experiences intranslatable across and between us. In exploring our own stories of work as an adjunct professor and as a tenured professor, responding to the directives and regulations of university governance and faculty practices, we found that we needed a different theoretical toolbox. This prompted our shift to Institutional Ethnography, which investigates systems of power rather than particularity (Smith 2005). Our experiences and stories as professors were not the focus; rather, they opened up a window into the workings of power.

Texts

Texts as they operate in institutions both organize work and are work. While texts can be subjected to discourse analysis or historical analysis, in Institutional Ethnography they are used to make visible the ways in which people’s work and experience are organized and the ways in which regimes of power are maintained and individual agency constrained. The texts themselves are not the focus, but rather are a form of evidence of social coordination (Smith 2005, Gerrard and Farrell 2013). Texts are not neutral, nor necessarily malignant in their effects. But they are pervasive and invasive in the daily lives of people.

In Canada, teaching and learning in teacher education programs takes place at an intersection of institutional expectations within the domains of higher education and government. Such institutional expectations include contractual obligations, institutional regulations, and local practices within universities as well as legislative acts and regulations of provincial government ministries and agencies. Institutional expectations are often formalized and articulated in regulatory and “official” documents. Practices and texts function as means of control in the university classroom over both professor and student, regulating and standardizing curricular choices and pedagogical strategies.

The work of academics is organized by textual practices that follow historical and cultural traditions and institutional expectations. One aspect of working in a university is to respond to and to organize one’s daily activities around textual practices that are coordinated with other people’s work. An example of this is the process of sequential communication that happens every year to determine tenure and tenure-track Faculty teaching assignments. The first step that is visible to us (though many bureaucratic steps precede it performed by other workers) is when Terry receives an email in the spring from the Secretary of the Dean that asks her for her teaching preferences. As a tenured professor she is assured work. It is nice of the (Office of the) Dean to ask for her preferences; however, according to the Senate By-laws and the Collective Agreement, it is the Dean’s prerogative to assign teaching. It is also Terry’s contractual obligation to teach what she is assigned to teach. Nevertheless, every spring she receives the same letter. She fills out a form, identifying which of the listed courses she would prefer at the undergraduate and graduate level. That form goes back to the Secretary of the Dean. It becomes a step in a process that is communicated through other forms that inform meetings and discussions, and an organizing text for the work of the Dean and other staff. The form in turn creates other documents that align with other documents, and a month or two later she receives two copies of a letter (not an email) in a sealed envelope in her mailbox to inform her of her teaching assignment. One copy she signs and returns, which is another step in a process of coordinated institutional practices.

Danielle, as an adjunct professor, does not receive an official request for her teaching preferences. Courses that are not assigned to permanent faculty are assigned to contract workers in a different series of communications, as “jobs” that are posted and applied for every term. Formally and officially, the faculty has a committee structure and process for contract appointments: Danielle’s application may go through a series of reviews, and may be subject to formal adjudication. However, the formal process is not always adhered to, and the process is also subject to personal favoritism. The situation of Danielle, as adjunct faculty, is relatively precarious, though some protections are still typically provided by Senate and Collective Agreement documents. This is emblematic of adjunct faculty in universities throughout Canada and beyond (Field and Jones 2016, Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations 2016, Wagner et al. 2008).

By examining and analysing both the documents and the process through which documents—and the work of creating and responding to them—are activated to impose constraint and control, differences of position and power become visible. Constraint is not limited to non-tenured faculty; nor is control to be assumed the prerogative of administrators. The system of textually organized work constrains each actor to their particular role in the process, much as a factory worker is assigned a particular tool to accomplish a discrete task within a rolling system, and the interrelationship of tasks and actors and the network of both formally mandated actions and informally maintained practices, control (or limit or regulate) the potential for any digression.

The beginning of a “problematic” might be to see the different experiences of non-permanent workers as embedded in a system of exploitation. How do adjunct faculty organize their work? How is their work coordinated through textual practices? What are their everyday experiences? Such questions might lead to a deeper understanding of the systems of the institution and relations of ruling that are maintained through work and coordinated through textual practices.

Institutional Contexts

Our research for this paper takes place at the nexus of several institutions and their domains of regulatory control. Regulatory control is applied through formal channels of bureaucratic and governmental relations and laws, as well as through informal channels of social expectations, habitus, and self-surveillance. Formal channels include the Ministry of Education, which funds and oversees public schools; the Ontario College of Teachers (hereafter referred to as OCT), an arm of the Ministry of Education that accredits teacher education programs (among other things); the Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Development, which funds and regulates universities; our university, governed by a Board of Governors and Senate; the Faculty of Education, an Administrative Academic Unit within the university administered by a Dean and two Associate Deans; and the Teacher Education program, overseen by the Associate Dean of Preservice. While the Dean hires and assigns teaching to faculty members, day to day administration and communication may flow from either the office of the Dean or the office of the Associate Dean, or may be communicated by administrative staff. Each of these layers of governmentality are enabled by textual practices and relations of ruling that are implemented and operationalized by the daily actions of faculty members.

Each faculty must follow university Senate By-laws and adhere to the Collective Agreement between the Board of Governors and the Faculty Association. Each university must operate under the regulatory bodies that control various aspects of licensing degree programs and funding formulas. Each professionally-certified program must meet the requirements of professional governing bodies—in the case of Bachelor of Education programs in Ontario, that body is the Ontario College of Teachers. The Ontario College of Teachers is the regulatory body responsible for both licensing teachers who have completed their degree program, and accrediting the faculties of education in the province. The OCT, therefore, has two avenues of oversight and control: at the individual level (licensing the teachers themselves) and at the institutional level (accrediting the faculties of education who provide their training under the Education Act). Such controls often exist in tension with the principle of academic freedom. These multiple regulatory bodies operate both subtly and overtly to control the impulses and activities of individual professors.

Converging fields and domains

In 1990, Bourdieu (1990) described the university as a “field of cultural production in the field of power and in social space” (124). A university in Canada operates in multiple fields of control and constraint, as a historic institution with its inherited culture and habitus; as an arm of the state, funded by the government (though the proportion of government funding has dropped in the past 30 years) and regulated through ministries of the government; as a cultural gatekeeper of professions and bureaucracies; and as a reflecting pond for the narcissistic impulses of those with power and privilege. The university, as institution, maintains and re-inscribes habitus, and this occurs and is coordinated through texts and discourse. Both professor and student are subject to “immanent necessity.” As Bourdieu describes it:

The relationship between habitus and field operates in two ways. On one side it is a relationship of conditioning: the field structures the habitus, which is the product of the embodiment of the immanent necessity of a field. On the other side, it is a relation of knowledge or cognitive construction: habitus contributes to constructing the field as a meaningful world. (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992/1996, 127)

For Bourdieu, “a field is a relatively autonomous domain of activity that responds to rules of functioning and institutions that are specific to it and which define the relations among the agents” (Hilgers and Mangez 2015, 5).

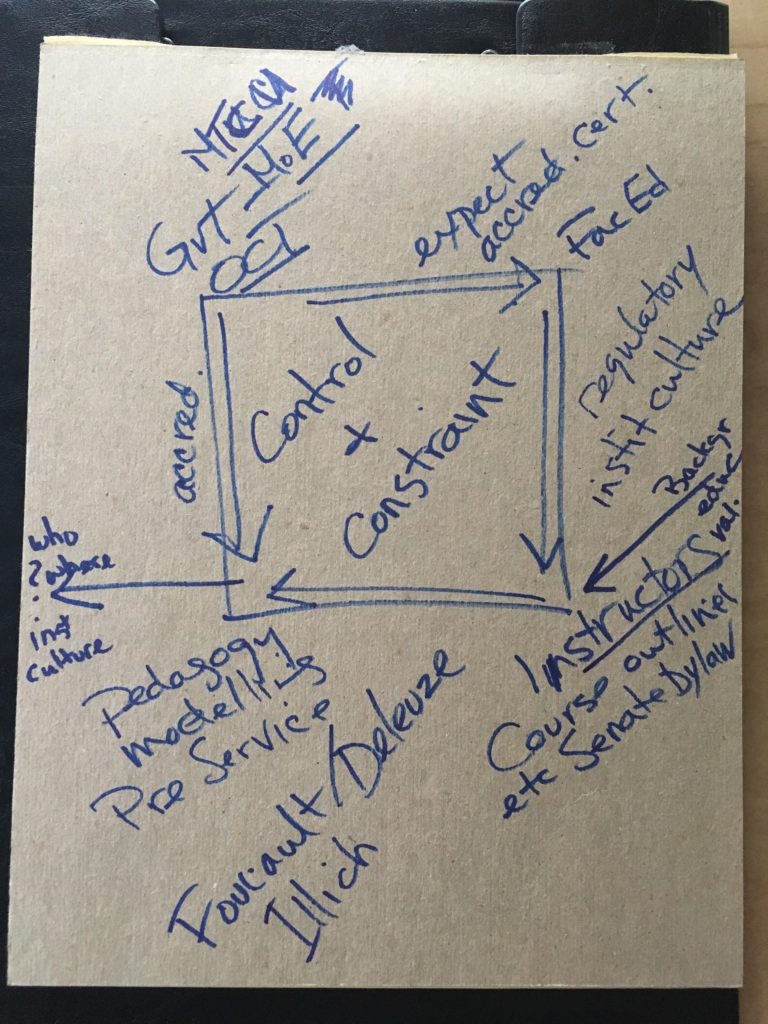

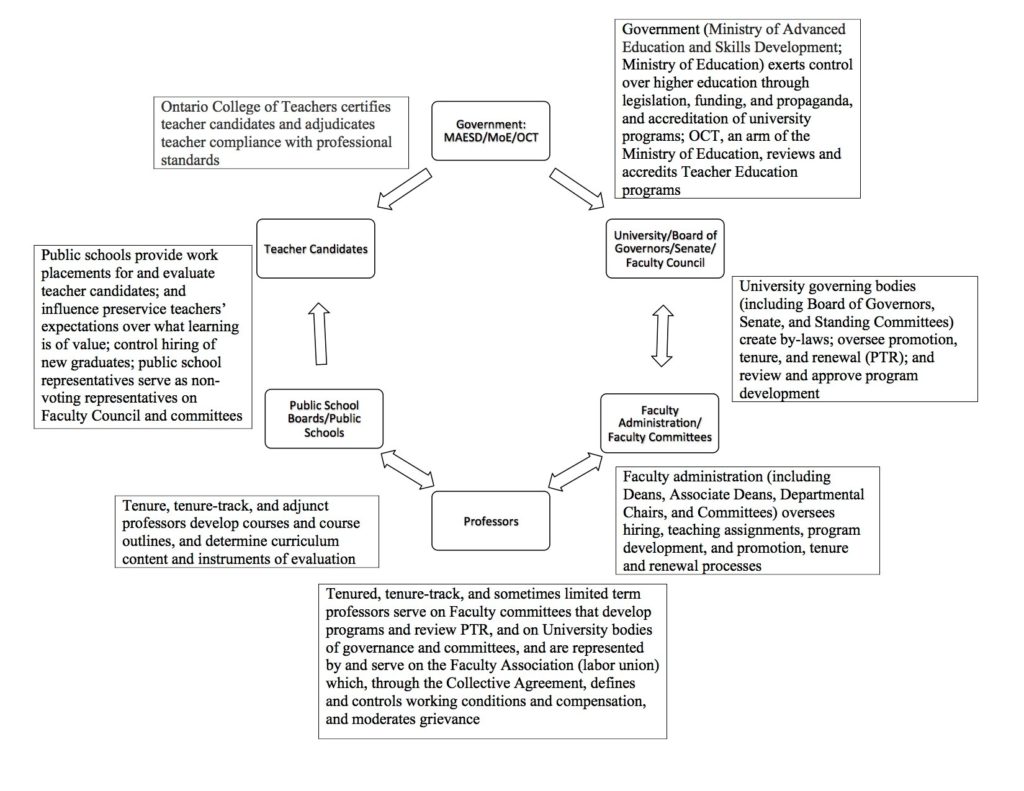

We conceptualize the multiple points of control in our program through Bourdieu’s concepts. At one of our meetings, we drew a diagram to depict some of our own emerging understandings of how governing professional bodies such as ministries of government and the OCT, professors, and preservice teachers interact and negotiate power (figure 1).

These relationships became clearer to us as time went on, and we created a more formal diagram of domains (figure 2). The fixed nature of the diagrams and the linear direction of the arrows don’t capture the depth and complexity of these intersecting, overlapping, and converging fields and domains, but serve to give a sense of some of the actors and relationships at play, and how we visualize these institutional contexts. Ministries of government exert power over faculties of education through the accreditation process. Faculties of education exert power over instructors through regulatory institutional culture and localized textual practices, such as course outlines and Senate By-laws. Instructors in the classroom control pedagogy and course content. These relations are what Dorothy Smith (1999) called “ruling relations.”

Institutions are social constructs, complex organizations of human activity that are historically and culturally situated (Weber 1904/1930). Institutions are maintained and continually re-inscribed by social practices that are coordinated through discourse and textual practices that organize work (Smith 2005). They are ideas as well as places. A university is the idea of higher education (Newman 1852/1996), and the actuality of localized practices and social organization mobilizes the idea of higher education. Professional programs of the university, such as law, medicine, and education, are subject not only to the regulatory mechanisms of the university, but also to their own governing professional bodies. Max Weber (1904/1930) describes the intertwining of institutional prerogatives and regulations as “the rise of bureaucratization and a ‘rationalist’ way of life” (240). Professional degree programs often include applied components, such as internships or practica. Teacher education programs in Ontario require teacher candidates to complete a set number of hours teaching in classrooms. The concrete and applied nature of practicum activities are reflected in mission statements and assessment strategies that include “learning outcomes” and “expectations.”

Performance-based assessment and goals-based learning are forms of indoctrination into a way of being in the world—ways of behaving and of inhabiting a body within a physical space (the classroom), and of knowing the world (valuing some forms of knowledge over others). At one end of the field (metaphorically, not theoretically speaking), professors may appear and may even believe that they have academic freedom to structure a course, plan curricula, and deliver it using pedagogical approaches of their own devising. However, individual agency is limited in all of the ways that Bourdieu, Weber, and Foucault describe, as cultural, discursive, and textual practices limit and delimit what can be done and what can be said (Bourdieu 1992/1996, Weber 1904/1930, Foucault 1972/1980). The controls within a department or faculty increase the tightening of boundaries, or become another of many conditioning factors of constraint, including self regulation. But the complexity of the university cannot be overstated. There are many “faculty”—some with administrative roles, senior full professors, untenured professors, adjunct professors, teaching assistants. This means that there are widely divergent responses to institutional mandates and different degrees of compliance with the regulating mechanisms of the institution.

Prescribing outcomes / Flattening difference

Provincially mandated practices

The Ontario College of Teachers carries out accreditation of teacher education programs at all faculties of education every 5 to 7 years. Only institutions with accredited Bachelor of Education programs can graduate teachers who will be licensed by the OCT to teach in public schools in Ontario, so accreditation is necessary and enforced. The accreditation process entails an extensive report on programming and a site visit that includes a review of classrooms and meetings with full-time and adjunct professors, which are voluntary but strongly encouraged. The on-site visits and review are completed by a small panel (Ontario College of Teachers 2015, 2017).[3]

While preparing for recent re-accreditation, our administrators sent out multiple requests to faculty to help with decorating of classrooms to give the appearance of (public) school culture, providing artefacts for a showroom that included videos of classroom teaching, participating in interviews with the accreditation panel, and revising course outlines to comply with OCT panel members’ expectations. Requests were always framed in the imperative, as directives, and were usually accompanied by tight deadlines. The immediate message to faculty was an implicit (sometimes explicit) threat that non-compliance might result at the institutional level in losing accreditation or, at an individual level, losing favor. One of the most contentious requests had to do with revising course outlines. Our university requires professors to provide a course outline (syllabus) to students (University Senate By-law 51). Course outlines become a contract between professor and student, and enforce compliance of both, by stipulating course content, assignments, due dates, and assessment criteria. Localized textual practices in these documents may be highly variable, and include, at the faculty or departmental level, expectations of formats, inclusions, and exclusions. Individual faculty create course outlines of a few pages with minimal information, or lengthy documents that include highly structured descriptions of class-by-class activities, prescriptive learning outcomes, and detailed assessment procedures. Course outline templates (figure 3) were disseminated by our Associate Dean prior to the beginning of the accreditation process. The template included a mandatory section for learning outcomes (noting parenthetically that these are “required” by the OCT).

The majority of our students are knowledgeable about the status of the course outline as a legal contract, and about how to leverage this information in their own self interest. In our experience, they come to our classes expecting a course outline that has detail on assignments and assessment, and explicit success criteria. Most want no surprises and no ambiguity. The reason for this pragmatism and risk-averse attitude is their entire previous schooling. They have been trained to think in terms of success criteria, and they will take this “operating system” (organizational theory, ethos, or modus operandi) with them as they prepare to teach Ontario curriculum in Ontario classrooms. Students’ expectations are also conditioned by their previous experience in university degrees they have completed, their experience with other courses in the Education program, their knowledge of regulations mandated by Senate By-laws, their participation in a community of practice, and by social group behaviours, often communicated through social media.

Our University has recently moved toward encouraging professors to provide prescriptive, inflexible, learning outcomes in course outlines. While the university continues to study the potential benefits and disadvantages of learning outcomes, an official Senate Working Group on learning outcomes has found that

The pre-determined nature of learning outcomes runs counter to the educational mission of universities, in that it does not allow for the intellectual ambiguity, uncertainty, and experimentation that advance knowledge” (University of Windsor 2016, 14).

However, there is increasing pressure at the faculty level to comply with increased standardization of course outlines. Learning outcomes are usually identified before the course even starts and professor and students have interacted. These are becoming a cultural textual practice at the departmental or faculty level. In some academic units, the Chair or Dean prescribes policy and may require instructors to follow a standardized format (in the case of Faculty policy, this may be mandated by Senate By-law).

Locally mandated practices

At several stages during accreditation preparation, reminders were sent out from administration stating that all methodology course learning outcomes identified on course outlines must align and comply with the learning outcomes in Ontario elementary and secondary school curricula. Administration then sent out an additional template designed to “provide concrete evidence” to the OCT of how our teaching was “explicitly” linked to Ontario public school curricula. Included was the request (couched as an imperative) that this be completed by each instructor (figure 4) and appended to each course outline.

The impetus for sending an additional template was the spotty compliance of faculty to previous requests to revise their syllabi with the first template, and to a string of subsequent requests that went largely ignored by tenured faculty. There was no institutional regulatory mechanism for enforcing compliance. This “task” fell between two institutional stools—faculty are contractually bound to carry out their duties as prescribed by Senate By-laws and the Collective Agreement. The Ontario College of Teachers controls the accreditation of the faculty, but does not control the work of faculty members. So it fell to the Faculty administrators, who felt under pressure from the OCT, to use their powers of persuasion—requesting, cajoling, reminding, scolding, and threatening (sending out dire warnings that if we did not comply the Faculty might not be accredited)—to attempt to gain the compliance of faculty instructors.

This localized struggle reflects some of the tension between academic freedom, which is a founding principle of higher education; and the pressure on professional degree programs to adhere to the dictates of professional oversight bodies. Individual professors may feel pushed to instruct in inflexible, prescriptive-compliant, outcomes-based ways. The result is like being caught between two walls moving inward, threatening to compact one’s pedagogy into the least possible space of individual freedom. The effect is a flattening—a flattening of pedagogy, a flattening of content, a flattening across disciplines and between instructors: a flattening of difference and an erasure of creative possibility. Some instructors may not feel that they have the freedom to break free, and so this flattening is cemented and re-inscribed. What is especially dismaying is how this ignores or even mitigates against acknowledging individual and cultural difference, and teaching and learning as an interactive relationship.

Compliance for all?

While we were working on our research project, planning focus groups, and looking at data related to our students, we also often met collegially between classes and outside of the university setting. In several of our conversations, the topic drifted to accreditation. Danielle had complied with the directives sent out by administration, and had filled in the accreditation addendum template created by our administration to align with curricular learning outcomes dictated by the OCT. This retroactively changed her course outline. She could not, however, give this revised version to students as she was already halfway through the course, and Senate By-law prohibits instructors from changing course outlines after the second week of classes. The revised course outlines were submitted to the office of the Associate Dean, and then added to the Accreditation “package.” Terry, on the other hand, had not complied—nor apparently had many or most other tenured professors. When Terry asked her tenured colleagues what they were doing about these requests (demands), they told Terry that they had ignored the emails; or had revised the course outline for only one of their courses; or had read the emails and refused. This was evident in reviewing our final Accreditation package: of the 31 revised course outlines provided, 26 were written by adjunct faculty.

Final thoughts

Institutional textual practices function to organize and coordinate the behaviour and work of both faculty and students. While tenured faculty may feel empowered to push back at what they perceive to be an incursion or intrusion on their academic freedom, job precarity may compel adjunct faculty to adapt and comply. As Saunders (2010) reminds us, teachers “[teach] in the way that they were taught and in the way that they were taught to teach” (72), and so this prescriptive-compliant paradigm carries forward into public schools. This has significant implications for music education, since standardized, outcomes-based education leaves little room for creativity and for difference, and continues to reify hegemonic structures both in the academy and in the music classroom.

We emerge from this inquiry with several provocations, framed by Action Ideal IV. How can we identify and subvert institutional mandates that undermine student difference and instructor autonomy? In what ways can we resist educational practices that are guided by accountability frameworks rather than by an ethic of care? How can we make the at times invisible effects of job precarity on curricula and pedagogy visible? The initial response must be at the individual level, recognizing the role each of us plays in ruling relations, through the everyday mundane activities of preparing course outlines and responding to requests or demands to “form filling.” The textual practices of the institutional work that academics perform daily is often trivialized, grumbled about, or completed without critical reflection. In other words, these activities are not examined as critical steps in a field of cultural production. Part of the answer also has to be colleagues talking to colleagues, especially colleagues with secure positions (tenured) listening and talking to colleagues in more precarious positions or who have insecure work. The relative isolation in which many of us work, in our offices and classrooms, may effectively block us from seeing how some of these forms of institutional practice impact the lives and work of others.

Acknowledgements

This publication has been undertaken as part of the Global Visions through Mobilizing Networks project funded by the Academy of Finland (project no. 286162) as well as the ArtsEqual project funded by the Academy of Finland’s Strategic Research Council from its Equality in Society programme (project no. 293199)

About the Authors

Danielle Sirek is an adjunct professor in the Faculty of Education and School of Creative Arts at the University of Windsor, Canada. Prior to teaching in higher education, she taught preschool through grade 12 music in Canada and Grenada, West Indies. Sirek received her PhD from the Royal Northern College of Music, UK. She also holds a Bachelor of Music from Wilfrid Laurier University (Canada), and a Master of Music from the University of Toronto (Canada). Her teaching and research interests include music teacher education, intersections between music education and ethnomusicology, sociology of music education, and arts education for social justice. Danielle also sings with the JUNO-nominated Canadian Chamber Choir.

Terry Sefton has performed as a chamber musician in Canada, the US, Britain, and France. She works with contemporary composers and artists in developing and performing new works. Dr. Sefton is Associate Professor at the University of Windsor where she teaches music and arts pedagogy in the Bachelor of Education program; and qualitative and arts-based research theory and methodology in the graduate programs. In addition to her performance-based creative work, she has published in academic journals and books. Her research interests include Institutional Ethnography, identity of the artist, the arts in higher education, music education, and sociology of the arts.

References

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. The logic of practice. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1992/1996. The rules of art: Genesis and structure of the literary field. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre, and Loïc Wacquant. 1992. An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brennan, Jason, and Phillip Magness. 2016. Are adjunct faculty exploited: Some grounds for skepticism. Journal of Business Ethics, Online at http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10551-016-3322-4

DeVault, Marjorie L., and Liza McCoy. 2006. Institutional Ethnography: Using interviews to investigate ruling relations. In Institutional ethnography as practice, edited by Dorothy E. Smith, 15–44. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Fagan-Wilen, Ruth, David W. Springer, Bob Ambrosino, & Barbara W. White. 2004. The support of adjunct faculty: An academic imperative. Social Work Education 25 (1): 39–51.

Feldman, Daniel C., and William H. Turnley. 2004. Contingent employment in academic careers: Relative deprivation among adjunct faculty. Journal of Vocational Behaviour 64: 284–307.

Field, Cynthia, and Glen Jones. 2016. A survey of sessional faculty in Ontario publicly-funded universities. Toronto: Centre for the Study of Canadian and International Higher Education, OISE-University of Toronto.

Foucault, Michel. 1972/1980. Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977. Edited by Colin Gordon. Toronto: Random House.

Gerrard, Jessica, and Lesley Farrell. 2013. ‘Peopling’ curriculum policy production: Researching educational governance through institutional ethnography and Bourdieuian field analysis. Journal of Education Policy 28 (1): 1-20.

Hilgers, Mathieu, and Eric Mangez. 2015. Introduction. In Bourdieu’s theory of social fields: Concepts and applications, edited by Mathieu Hilgers and Eric Mangez. London: Routledge.

MayDay Group. 2012. Action ideals. http://www.maydaygroup.org/about-us/

action-for-change-in-music-education/#.WcVWjtOGOgQ

Newman, Henry. 1852/1996. The idea of the university. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ontario College of Teachers. 2015. Accreditation Review Guide for Participants. https://www.oct.ca/-/media/PDF/Accreditation%20Review%20Guide %20for%20Participants/accreditation_review_guide_e.pdf

Ontario College of Teachers. 2017. Program accreditation. http://www.oct.ca

/public/accreditation

Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations. 2016. Professors calling for fairness for contract faculty at universities across Ontario. https://ocufa.on.ca/blog-posts/professors-calling-fairness-contract-faculty-universities-across-ontario/

Ovetz, Robert. 2017. Migrant mindworkers and the new division of academic labor. The Journal of Labor & Society 18: 331–47.

Smith, Dorothy E. 1987. The everyday world as problematic: A feminist sociology. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Smith, Dorothy E. 1990a. The conceptual practices of power: A feminist sociology of knowledge. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Smith, Dorothy E. 1990b. Texts, facts, and femininity: Exploring the relations of ruling. New York: Routledge.

Smith, Dorothy E. 1999. Writing the social: Critique, theory, and investigations. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Smith, Dorothy E. 2005. Institutional ethnography: A sociology for people. Lanham: AltaMira.

Saunders, Jo A. 2010. Identity in music: Adolescents and the music classroom. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 9 (2): 70–78.

University of Windsor. 2016. Report of the Senate Working Group on learning outcomes. University of Windsor, Windsor, ON. http://www.uwindsor.ca/

secretariat/sites/uwindsor.ca.secretariat/files/sa160610-5.2.2_senate_wg

_on_learning_outcomes-report.pdf

University of Windsor Senate By-Laws. 2017. http://www.uwindsor.ca/

secretariat/49/senate-bylaws

Wagner, Anne, Sandra Acker, and Kimine Mayuzumi, eds. 2008. Whose university is it, anyway? Power and privilege on gendered terrain. Toronto: Sumach Press.

Weber, Max. 1904/1930. The Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. New York: The Citadel Press.

Methodology courses in the Bachelor of Education program align with subject areas in elementary school, such as science, physical education, language arts, and music. In Ontario, music methodology courses for elementary generalist teachers focus on components of the Ontario Arts Curriculum. Course content usually emphasises European “classical” music.

2 Senate is a legislative body made up of tenured faculty and student representatives. Senate By-laws regulate faculty and student responsibilities and administrative processes.

3 Specifically, two members of the Council of the Ontario College of Teachers, one member experienced in a professional education program or in teacher education program evaluation, one member nominated by the institution, and one member with expertise in the specialized area of the faculty (if applicable).