DANIEL J. SHEVOCK

Keystone Central School District, Pennsylvania (USA)

January 2026

Published in Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 25 (1): 143–77 [pdf]. https://doi.org/10.22176/act25.1.143

Abstract: This essay considers ways in which Music Education may function as a religion—its moralistic, ritualistic, and transcendent dimensions—through an ecological-praxial lens. Drawing on the Catholic intellectual tradition and liberation theology, Platonic transcendence is contrasted with relational Trinitarian understandings of transcendent Beauty as dynamic relationship. Music Education is considered a ritual system cultivating, from its specialized outlook, virtuous people—a contemporary vir perfectus—and conserving myths of economic success and social compliance in schools. An ecological praxis is grounded in interdependence, love, and creation, giving people lived human and divine relations. While Music Education shares many outward features with religion—types of ritual, devotion, and moral development—it lacks religion’s most meaningful salvific and metaphysical dimensions. Music Education is not fully a religion but may participate in religious works reimagined through ecological and relational praxes.

Keywords: Music education philosophy, ecological praxis, transcendence, liberation theology, relationships, beauty, trinity

I am a window radiating the light of the sun. Over years I have been scuffed, cracked, shattered, and repaired many times over. The daylight shining through me is not as clear as it might have been when I was new. But this is how the Lord intended us to be. God’s very name is Love. Love is relationship, and human relationships, duties, and commitments toward one another wound us. All relationships with others do. As beams of light dance through my flaws, illuminating this room imperfectly, creating unexpected rainbows, shadows of hope, and traces of clarity, I begin with the very beginning (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Wounded window, glowing.

Figure 1: Wounded window, glowing.

Opening Reflection: Work, Music, The Garden, and the Fall

From nothing, a tone emerges. In the first artistic act, an ecological act, God sang all matter and time, all life, and finally, human life with its material and spiritual existence, and put them in an idiosyncratic position as both stewards and co-creators. Humans were formed to work and play in the garden, “to cultivate and care for it” (Gen 2:15 NABRE), to eat, and create beauty from their innocence, in free cooperation with their creator. Then the Lord intoned, “very good” (Gen 1:31 NABRE). Not having original sin, Adam and Eve fell from this state of grace by choosing to eat of the prohibited tree. With them, all creation fell, including their creative work. Beautiful things became toil and burden. People envied, injured and killed one another, and damaged creation. Much philosophy begins, in some way, by looking bravely at toil, burden, and suffering. These broken things are an inescapable reality, an abyss that philosophers bravely face and scrutinize. However, while recognizing these, Christian philosophers are called to begin from a more optimistic position—not only the cracks, but the dancing of the light through our dearest, tender wounds. God is Love.

Introduction

My curiosity is rooted in what is termed the Catholic intellectual tradition (described later in this paper) because that tradition has presented me with my intellectual roots.[1] I do not believe I can escape those roots, though historically people have tried to escape their roots, often to personal, economic and ecological devastation. When people decide to become music teachers, we give professional lives to teaching and learning music. We often begin careers young, fit, full of naïve energy, and ready to conquer the world. Then we come face to face with institutionalized schools; parents who we see as too cavalier or, alternatively, overbearing; and children facing very real social problems, such as classism, ableism, and racism. Professional lives can be understood as precious gifts that each teacher gives—from graduation to retirement, and often beyond. Educators dedicate lives to one discipline which they seemingly must have some sort of faith in. Senses of mission sustain us through both pleasurable and dreadful moments. Dedication to the discipline can lead us to see Music Education, specifically as it emerges in schools, as a religion with its rituals, universal scope, and transcendent creative experiences. That said, up front I want to make it clear that while it may be common within religious circles to note the ways secular phenomena operate as religious, and Ivan Illich has strongly associated educational institutions to modern religious churches (discussed later in this paper), I am interested in synchronicities—the ways Music Education operates similarly to and differently from religion in general, and more specifically my religion, as that is the one with which I am most familiar. An ecological approach, an approach that places together seemingly unrelated living beings within specific environmental communities, can draw together and hold distinct “Music Education” and “religion”; but this ecological approach will require some humility—humus means earth[2]—an appreciation for uncertainty that may grow into greater certainty as seeming unrelated ideas are brought into life together.

Catholic Anarchist, Servant of God Dorothy Day (2017) wrote in her journal, “So often one is overcome with a tragic sense of meaninglessness.… We are placed here; why? To know him and to love him, serve him by serving others, and so attain to eternal life and joy” (16). St. John Paul II calls art a difficult gift: “a gift for which one must pay one’s entire life” (Wojtyla 2021, 32–33). With this sense of service in my daily labor, in an impoverished, rural school district, I face each new day’s challenges and teach these specific kids’ musics as best I am able. But have I dedicated my life to another religion? Perhaps Music Education is a secular religion? Does my chosen field have its own sense of service, transcendence, and meaning, its own sense of life and joy? Are these at odds with Catholicism?

As a professional field, education has long been hallowed by those maintaining the secular values that dominate the Global North as well as a revered icon to be acquired in the Global South. Starting in the 1960s and 70s, Catholic social critic Ivan Illich compared “the myth of social salvation through schooling” to “the divine rights of Catholic Kings” three centuries earlier (Illich 2012, 120), and as offering “the central myth-making ritual of industrial societies” (121). For Illich (1978), education is similar with religion in that both employ ritual to maintain certain myths. Writing four decades later, Prakash and Esteva (2008) extend Illich: “While the global mission of the Church is to save souls, the global mission of the educational system is secular salvation” (17).

In this line of argument, it is irrelevant whether, or to what extent educational professionals understand themselves as “secular.” Rather, the mission is itself “secular salvation,” being saved from being labeled a drop-out and being kept from prosperity in that society’s capitalistic understanding of escape—to use a synonym of salvation. To exemplify, such escape/salvation has been identified by Bates (2016) in relationship to urbanormative ideologies in Music Education, where undergraduate Music Education students reflect the urbane, “belonging to the city” (167). Music Education saves uncivilized rural youth, instilling a longing to live elsewhere. That escape emerges through learning “suave, sophisticated, debonair, worldly, cultivated, cultured, civilized, cosmopolitan, smooth, polished, refined, self-possessed, courteous, polite, well-mannered, civil, charming, gallant” (167) musics.

In this line of discourse, Music Education would be a religion, with rituals, an approved understanding of the deity, dogmas, heretics, and an assembly of saints. As I read these analyses, I wonder to what extent Music Education[3] shares goals and functions with religion: What is the mission of Music Education? What do the rituals of Music Education look like? What myths do these rituals perpetuate? From what or whom are music students being saved? Perhaps most importantly, is Music Education indeed a religion? If it is not a religion, why then do some claim it is, or is almost a religion?[4] The question of religiosity is not new ground for Music Education, but rather a perennial question with which, I have come to feel, Music Education philosophers ought to wrestle.

In this paper I address the question posed in the MayDay Group Colloquium 35 call for proposals: “Utilitarian, aesthetic, and praxialist Music Education philosophies have shaped and guided Music Education practices in many countries. What might be the next historical turn in Music Education philosophy?” Two of these three philosophies, aesthetics and praxialism, currently shape Music Education systems at local, national, and international levels[5], and, while each builds on and transforms aspects of existing Music Education practice, can be analyzed to interpret how Music Education is alike to and different from a religion, which is not the aim of this paper. The third, utilitarianism, does not seem to rise to the challenge of offering a philosophy of Music Education, but is an unreflected-upon bias for many music teachers, and the inhumanly efficient educational system itself—I analyze educational utilitarianism’s religious ritual with an analysis of the PSSAs (Pennsylvania System of School Assessment) as ceremony. This paper is written within the realm of morals (or ethics, as I make no practical differentiation in this paper) taught through music. I begin the current analysis by reading the history of Music Education in the institutionalization of teaching values, especially in the Middle Ages (Illich 1978) and the links between the medieval schools and contemporary secular educational systems, with an eye on Wayne Bowman’s praxialism.[6] I then read Bennett Reimer’s 1963 dissertation, which suggests aesthetic Music Education serves the same function for modern people as a religion had in previous generations.

I then clarify just what a religion is. A religious perspective, a theology, can, and perhaps even ought to, guide music teachers and learners. My religious tradition, the Catholic intellectual tradition, offers a praxial alternative to transcendent Beauty—one that is both transcendent and relational, which is helpful when facing the ecological crises—e.g., climate change, e-waste, species collapse, water pollution—overshadowing our lives today. In 2015, Pope Francis promulgated what is considered one of the most impactful and effective statements of the ecological condition, Laudato Si, which develops an integral ecology based on the writings of Francis of Assisi to face these challenges with joy and authenticity. For instance, understandings of climate change and e-waste entail “seeing the mysterious network of relations between things” and require considering our earthly home as a “common good”—the integral approach to species collapse, the fault of “short-sighted approaches to the economy” centers the worth different species have “in themselves”—the water challenge is connected to both human health, poverty, and aquatic ecosystems, with this approach accepting potable water as “a basic and universal human right” (Francis 2015, n.p.). Pope Francis was building on a Catholic intellectual tradition that had already recognized the ecological challenges as central. In a 2010 message for the celebration of the World Day of Peace, Pope Benedict XVI recognized that if we want to nurture peace, we must defend creation. Benedict advocated our “close contact with the beauty … of nature” brings us into “a certain reciprocity: as we care for creation, we realize that God, through creation, cares for us” (Benedict XVI 2010, n.p.). For Catholic scholars following the Catholic intellectual tradition, our conceptions of ecology, beauty and the creator are unified.

A Catholic-trinitarian understanding of Beauty as transcendental and relational is coherent with what I have previously suggested is our field’s historical turn (see Shevock 2017). The goal of this paper is not, then, to recommend Catholicism in specific, but use it to exemplify a historically rooted, ecological-religious turn that Music Education seems to be making. The next historical turn is ecological, and religion is part of that ecological shift in consciousness, just as is Music Education.

A Short Aside On Music Education Spirituality Discourse

Music Education has offered many papers in recent years on spirituality. To exemplify, Anglican clergy-member, June Boyce-Tillman (2013) utilized Greek Mythology to typify the human search for spiritual experience through music. Some relevant points include beliefs about the human soul—breath, spirit, and mind—and the world soul, which has implications for intercultural understanding. She argues that the secularization of culture demoted musics relevance to “mere entertainment” (29), but that music has the power to draw our attention to the Good, the True, and the Beautiful, which are discussed later in this paper. Yob (2011) utilized Tillich and Maslow (also discussed later in this paper by Reimer) to unpack what spirituality is, and how it is relevant, both as religion and morality, to the work of Music Education as spiritual education. Yob warns against conflating morality with spirituality and suggests spirituality education can teach for self-actualization and peak experiences. Mindfulness arises as helping students become accustomed to silence and resist busyness. Students can be directed to “embrace [silences], and … attune themselves to them so that the spiritual power of the music can take hold” (47). This aspect of spirituality was present in the work of Music Educator Satis Coleman, in the first half of the twentieth Century (see Shevock 2015), a music education scholar who identified her work as heretical. However, this paper is more directed to religion and its relationship-building aspects; what is called ecology.

On the Catholic intellectual tradition

The term Catholic refers to all rites, including but not limited to the Roman rite, that are in communion with the pope, and the term Catholic intellectual tradition describes various scholar’s writings “stretching from Origen in the third century to Charles Taylor in the twenty-first” (https://www.marquette.edu/mission-ministry/explore/catholic-intellectual-tradition.php). This paper is not a work of apologetics, but an apologetics aside is appropriate for readers who prefer I use a derogatory and outdated Protestant term for Catholic—Roman. This writing is appropriately named part of the Catholic intellectual tradition, and not “Roman” for two reasons. Firstly, this church is called the Catholic Church, and not the “Roman” Catholic Church (https://www.vatican.va/). Secondly, phrase “Roman Catholic Church” arose in the Anglophone as a 16th Century slight which

originates as an insult created by Anglicans who wished to refer to themselves as Catholic…. Different variants of the “Roman” insult appeared at different times. The earliest form was the noun “Romanist” (one belonging to the Catholic Church), which appeared in England about 1515–1525 … the noun “Roman Catholic” (one belonging to the Catholic Church) … was coined around 1595–1605.… This complex of insults is revealing as it shows the depths of animosity English Protestants had toward the Church. No other religious body … has such a complex of insults against it woven into the English language as does the Catholic Church. Even today many protestants who have no idea what the origin of the term is cannot bring themselves to say “Catholic” without qualifying it or replacing it with an insult. (Catholic Answers Staff n.d.)

Anti-Catholic hate crimes are also on the rise, particularly in North America. To exemplify, in Canada the year 2022 saw a 260% increase in Anti-Catholic hate-crimes (O’Neill 2022), resulting from deep-rooted bias.

In contrast, the phrase “Catholic intellectual tradition” is common in university mission statements, theology, scripture studies, Christian philosophy, and religious music writings denoting a growing body of writings emerging across cultures with a Catholic identity. The Catholic intellectual tradition is comprised of but not limited to cultural heritage from the past: “the classic treasures to be cherished, studied, and handed on; and the way of doing things that is the outcome of centuries of experience, prayer, action, and critical reflection” (Hellwig 2000, 3). Additionally, the Catholic intellectual tradition offers Catholics a “way we have learned to deal with experience and knowledge in order to acquire true wisdom, live well, and build good societies, laws and customs” (Hellwig 2000, 6). It is in this way that, at least for Catholic scholars, the Catholic intellectual tradition offers insight into everyday music teaching and learning, as well as Music Education scholarship and research. The Catholic intellectual tradition, particularly one that draws from medieval scholarship, offers, in this way, an underexplored and distinctive approach to Music Education spirituality scholarship.

Music Education and Character Education in the Middle Ages and Today

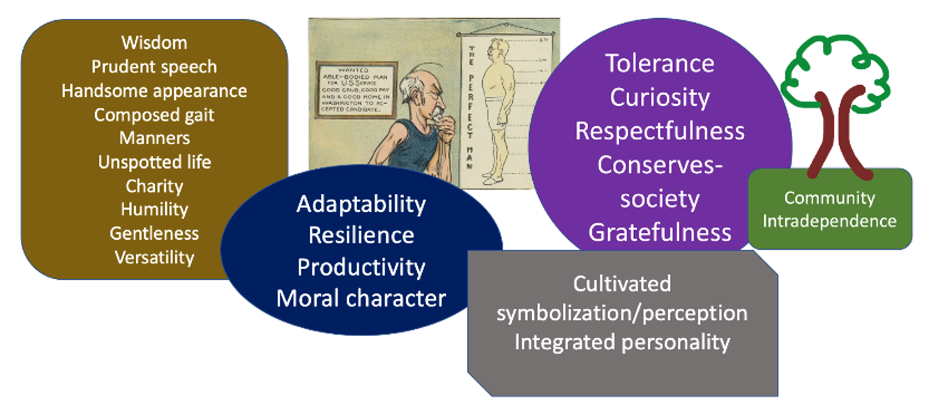

The question of a historical turn for our field is, to be obvious, a question of history. While aesthetic and praxial philosophies have dominated recent decades’ ethical discourse, the ethical roots of these discourses can be found in the Middle Ages. According to Mark, Boethius’s work marked the “slowdown of progress” (Mark 2002, 25) that typifies the Middle Ages. This opinion seems common, even where it is not entirely founded. The medieval period, for instance, saw rapid advances in technologies such as gunpowder and horseshoes, and the invention of paper, the hourglass, mechanical clocks, windmills, the paper mill, the dry compass, the wheelbarrow, crop rotation, spectacles, horse collars, central heating through underfloor channels, the chimney, machine clocks, improved water mills, and, in the fine arts, oil paint; as well as important scientific ideas such as magnetism, Arabic numerals, and the Western university itself.[7] Boethius’s late classical writing, De Institutione Musica, became the “accepted text” for centuries. As Christianity spread and gained strength in Europe, civil and religious authorities were fused. To exemplify, Sturmi of Falda,[8] an eighth century teacher, held to a Boethius-infused theory of vir perfectus—the perfect person. There were two branches in the “Old Learning” (eighth century)— letters and conversatio. Sturmi cultivated wisdom, prudent speech, handsome appearance, composed gait, upright manners, unspotted life, charity, humility, gentleness, and versatility (Jaeger 1994, 25). This idea of cultivating vir perfectus can be seen throughout the Middle Ages.

Music and physics, in medieval education, were viewed as the paths to ethical education; the idea being that a person’s outer grace parallels inner grace. Inner grace was the goal of ethical education. Education in music was intended to cultivate grace, modesty, and the golden mean—a person not being overly soft or harsh, not overly loud, or quiet, etc. The theory of medieval Music Education was influenced by ancient authors, especially Plato, Cicero, and Boethius. Harmony was given a high position, because inner harmony was intended to cultivate outer harmony. Music, as part of the quadrivium, was a core subject, and as one of the seven liberal arts, of high importance, because it coordinated the inner soul of each person with nature, including the whole cosmos, the microcosm to the macrocosm. Music Education was ethics education, which can be identified as character education.

Character education seems to have been and currently is a part of Music Education. Music educators are supposed to help cultivate character in people. Today, music teachers want students to become versatile, gentle, humble, as well as composed. The music we choose has a base level of social appropriateness. However, Music Education is not seen as the primal way character education is taught. My own school district’s mission includes adaptability, resilience, productivity, and moral character,[9] and these virtues are to be part of every subject—not just music and physics. To exemplify the link between medieval and contemporary Music Education, let’s begin with a Praxial philosopher who has been an influence on both the MayDay Group and my own thinking. An analysis of the writings of every praxial writer would be beyond the scope of this paper. Connections between his work and other praxial writers will need to be made elsewhere.

Praxial Music Education and a Another Vir Perfectus

In a 1994 paper, “Sound, Society and Music ‘Proper,’” Wayne Bowman critiques the essentialist notions of musics. The essentialist notion “wrongly constrict[s] the range of experience considered ‘properly’ musical, [and] falsely promises uniform criteria by which the worth of all music (properly so-called) may be evaluated … [it] invariably marginalizes certain musics at the expense of others” (Bowman 1994; Mark 2002, 204). Essentialism is believing everything has an essence that can be separated from other things in their essence. This is a position that moves well beyond merely believing in essences at all. For Bowman notions of musics ought not be detached from social values—musical and social values are entangled. Musics are integral features of human life and to separate these social functions into extra-musical realms is inappropriate, philosophically. Music is not a thing in contrast to the social world.

While the current analysis reinforces Bowman’s insights, the challenge to praxialists, myself included, emerges not from praxialisms opening musics to their social contexts—these are essential in understanding musicking (Mark 2002). Rather, it comes in narrowing praxialists’ horizon to the mere human. Bowman continues, “musics are definitively human activities whose richness does not survive apart from the human contexts of which they are part. Musics are socially and politically (and by extension, morally) significant enterprises” (as cited in Mark 2002, 204). The religious worldview may be able to offer a more ecological praxialism, which is able to recognize the creative potential of creation, humans included, but not automatically exclusively so. We see that Bowman places the moral within the political, the moral lessons of life, which include musics, within the political aspects of life, which include musics.[10]

Does using the concept of ‘essence’ make me, in Bowman’s analysis, an essentialist in the same way aesthetic philosophers he is critiquing are essentialists? I do not think so. Believing there are things with an essence beyond the material is not the same as believing music can be separated from the social world in its definition, experience, or teaching. And in experience, many praxial writers, myself included, have drawn on the phenomenological tradition of Husserl, Bergson, St. Edith Stein, and others within entirely praxial Music Education contexts. Bowman seems to be arguing against a “pristine” (Mark 2002, 204) essentialism in music that misses a lot. In that, I agree with Bowman’s critique of essentialism. Pure philosophical immaculateness seems to be a challenge to a full understanding and teaching musics in school because schools are in no way pristine. One does not need to over-abstract—but that does not mean there is no benefit to some abstraction either.[11]

Finally, Bowman does, in his own way, reflect the medieval concept of Music Education to cultivate moral gentility. Music teachers following Bowman’s suggestions “would be dedicated to nurturing tolerance and curiosity as well as refining tastes; to enhancing the ability to imaginatively identify with others; to imparting respect for the sonorous world and the sheer joy of musical doings within it; and to nurturing the kind of society in which the musically educated embrace with gratitude startingly different musics and take pleasure in each other’s eccentricities” (Mark 2002, 205). To place Bowman’s philosophy within a medieval perspective, then, would be to define the gentleperson as having cultivated the following virtues: tolerance, curiosity, respectfulness, conserving toward society, and gratefulness—nurturing the vir perfectus. Another praxialist may emphasize other virtues. For instance, Vincent Bates (2013) emphasizes community and intradependence, which leads us toward the more ecological praxis recommended in this paper. As such, without being exhaustive of the literature, it might be said that, in some way, praxialism can be placed in relationship to cultivation of the vir perfectus, and therefore to medieval religion and education (see also Taylor 1961). This perspective does not, however, admit to Music Education being a religion.

A Glimpse into Reimer on Music Education as/and a Religion

Now that connections between medieval/religious education and praxial education are made, let’s turn our attention to the other dominant philosophy in Music Education—aesthetic education. The leading Music Education philosopher of the 20th Century, Bennett Reimer, noted many similarities between Music Education and religion. In his 1963 dissertation, Reimer recognizes that both religion and art exist in every culture, that art is used in service to spiritual needs, and the arts bring purpose and meaning to religious ritual, and that even in secular art, “an aura of sacredness pervades” (1). Rather than analyzing Reimer’s full oeuvre, which would be beyond the scope of any single paper, I will focus on his dissertation to open possibilities for understanding Music Education and religion.

For Reimer (1963), the source of experience “is a transcendental Being which embodies, and which holds power over all possible human goods” (2).[12] However, he suggests that in traditional, orthodox religious cultures, music is connected to the profane, rather than the sacred. In this view, while arts spring from the divine thought and creation, arts operate, in some way, on a lower plane of existence than true religious experience of the divine source. Religious experience is defined as bringing individuals into a relationship with God through manipulation of religious symbols. All religious experiences are “saturated with aesthetic quality” (2). Musical experiences are only religious if they relate the individual to God.

However, Reimer (1963) identifies himself with non-orthodox Christian Liberalism. The religious liberal traditions are diverse but, in general, reject the idea of a supernatural Creator. God is defined to exclude the supernatural by individuals who craft a “personal religious philosophy” (4). Accordingly, a religious worldview does not depend on the existence of a supernatural Deity, but religious experience is satisfied in other ways. Susanne Langer’s transformation of human needs, such as the needs fulfilled traditionally by religion, into symbols becomes central to Reimer’s philosophy. Reimer also uses theologian Paul Tillich, who advances the idea that, “the old, orthodox symbols still retain much of their power, but must be reinterpreted in the light of modern knowledge of the world and of the working of man’s mind” (6). The definition of God, then, becomes an existential one, as that which essentially concerns a person. He sees modern people as having progressed beyond the orthodox view of religion, but because of the disruptions affecting people today, such as caused by wars, technological progress, and economic changes, people need the symbols that are now offered by Modern Religious Liberalism.

For Reimer (1963), “the very same elements in the nature and condition of man allow for both religious experience and aesthetic experience to happen and lead him to cultivate these experiences” (15). The function of aesthetic experience is to provide perceptions which may be named religious. In his conclusion, Reimer draws extensively on Carl Jung, who theorized that humans need to integrate their personality with the world, and that aesthetic and religious experiences help combat estrangement: “the highest good in the life of man is the development of his consciousness of himself and his world—the cultivation of his power of perceiving” (266). For Jung, religion is not about Faith, but experience. To our field’s conception of vir perfectus, Reimer adds the cultivation of perception through symbolization, and an integrated personality.

Reimer’s (1963) understanding of religion, and his aesthetics, as a result are entirely materialist. In reducing religious experience to symbols, experienced within the human brain, he reduces all meaningful existence to the material. Reimer’s materialist liberalism seems to override his Christianity, especially in his use of John Dewey’s view that belief in a supernatural God is an “encumbrance” (5). When Reimer concludes, along with Jungian psychology, that the highest good for persons is the cultivation of perception, this does not seem to be at all what Christianity teaches. Jung seeks “the common groundwork of humanity, predisposing the individual to think and act as the human race has thought and acted for countless generations” (268), Reimer’s philosophy may very well bulldoze over cultural differences. However, Faith is central to Christian scripture. “Faith is the realization of what is hoped for and evidence of things not seen. Because of it the ancients were well attested” (Heb 11:1–2 NABRE). The Jungian viewpoint of religion is very subjective and privileged—what happens in psychology, in-between the ears, is a small part of what Christian religion claims is the way. Ultimately, as a Catholic Christian, Reimer’s liberal Protestant approach to religion does not, at times, seem Christian at all. In the Catholic tradition, God is personal, supernatural, super-material, and very much real. This is documented by Reimer, who recognized the Catholic Church as preserving its credal function, objectifying the psychic symbols of the West, which is beneficial to mental balance. In contrast, Reimer describes Protestants as more mature; and mature churches no longer serve modern individuals because of modern science. From a Catholic perspective, St. John Paul II wrote of beauty as fragments of God, who is alone absolute beauty. These fragments draw us in, attract us, but “it’s not an abstract experience that is purely intellectual” (Wojtyla 2021, 25).

Additionally, unified conceptions of a transcendent Beauty as singular may reinforce a worldview that emphasizes God’s oneness. This is scriptural: “Israel, remember this! The Lord—and the Lord alone—is our God” (Dt 6: 4 NABRE). However, in emphasizing oneness/transcendence the Christian God can become distant. Returning to Reimer’s God—to the extent God exists, God is simultaneously too small for the Catholic conception—fitting within an individual’s brain—and too distant. To the extent that Reimer points toward transcendent Beauty, perhaps he is pointing toward the God of Plato more than the God of scripture, at least as expressed in the Catholic intellectual tradition, and I suspect, many liberal Protestant authors as well.

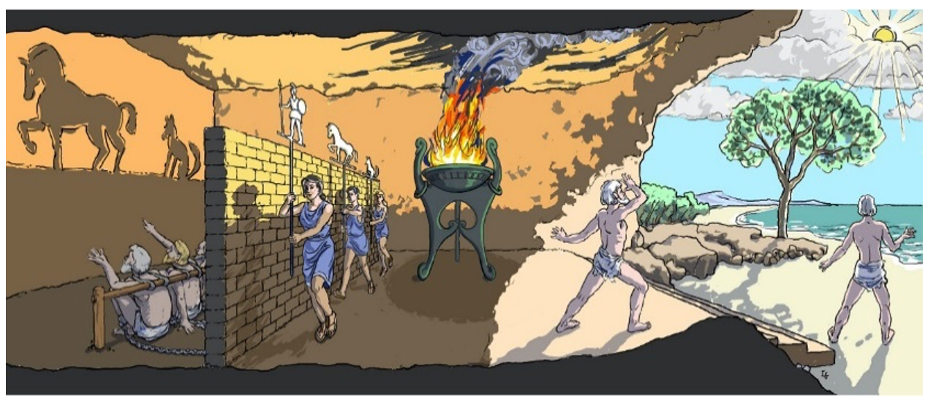

In the Platonic tradition, human and nature’s material realities obscure the human experience of God. To exemplify, in Book VII of the Republic, Plato formed his well-known allegory of the cave (see Figure 2: Plato’s cave). Within the cave are several shackled human beings who, unable to even turn their heads, have lived their lives underground in the dark, grasping toward a little, sporadic light on the cavern wall. They spend their lives contemplating the light and shadows cast by puppets at play within their vision. “Like ourselves … they only see their own shadows, or the shadows of one another, which the fire throws on the opposite wall of the cave” (Plato 1998, Book VII). And later, “suppose once more, that he is reluctantly dragged up a steep and rugged ascent, and held fast until he is forced into the presence of the sun himself, is he not likely to be pained and irritated? … He will require to grow accustomed to the sight of the upper world” (Plato 1998, Book VII). In this view of the “upper world,” the spiritual world, material reality serves to obscure reality. Perhaps this Platonic conception of the extra-material bears some hint of the nature of God, but a Catholic ecological-praxialism offers a different approach, which is shared in the next section.

Trinity, Relationship, and a More Catholic Ecological-Praxialism

“Praised be You my Lord with all Your creatures.” St. Francis of Assisi

[14]

In contrast with Reimers view of traditional and Liberal Christianity, in the Catholic tradition, God is understood as trinity, that is a relationship, from the very beginning. “In the beginning the Word already existed; the Word was with God, and the Word was God… Through him God made all things” (Jn 1:1-4 GNT). There is no single, stable light outside of the cave, but a relationship as the ultimate, transcendental reality. Rather than a Platonic God, the Catholic understanding of God as relationship celebrates relationships, nature, and communion. When we say “God is Love” we do NOT mean love in some abstract, untouchable, unencountered way, but rather a living of relationship. God is creator of not merely the transcendent immaterial realms, but the material universe, entirely, and it is good. Humans are called into relationships. Trinitarian experiences in nature, because of accepting that God is relationship, does not obscure our vision of the transcendent Being as unchangeable singularity but are the plan for our relationship with the triune God, who is itself relationship. As such, the Catholic tradition gives birth to St. Francis, with his “Brother Sun/Sister Moon,” as well as Catholic social teaching as lived out by Dorothy Day, S.O.G., Nicholas Black Elk, S.O.G. catechist and medicine man, and St. Oscar Romero. Prayers to the saints, and the Queen of Heaven do not obscure the Catholic experience of God, as it must in the Platonic perspective, but are rather the relationships God meant for us to have. The Catholic author Dante Aleghieri’s (1472/1997) understanding of Hell is as unmoving and frozen detachment. “He laid fast hold upon the shaggy sides; \ From fell to fell descended downward then \ Between the thick hair and the frozen crust” (Inferno: Canto XXXIV). In contrast with this frozen conception, the triune God is Beauty, but that beauty is beauty in action, a verb—Beautying. In words spoken by St. John Paul II in a 1962 retreat, “God not only is, but God acts. He acts by creating. But he acts particularly in relation to the human person” (Wojtyla 2021, 29–30).

Then there are the angels, other people, and non-human animals we encounter every day. People have interrelating duties with all of them, and as such, to ourselves (See Figure 3: Trinity). The dead are not dead but are also part of interrelating duties we have along with one another. Because of the materiality of the Catholic transcendents—Truth, Goodness, Beauty—I have come to believe we mean something different from one another when we talk about music, and art, and beauty. Beauty cannot be a stable, unmoving, frozen thing out there—the Platonic light, which is the Catholic hell—but relationship. The Catholic position is, resulting from the nature of God as triune relationship, a more praxial position by essence; and Catholic scholars who have put forth more transcendent unitarian conceptions of Beauty over the decades have likely been influenced more by Plato than by the scriptures and Catholic intellectual tradition.

To further exemplify the understanding of the Trinity in the Catholic tradition, liberation theologian Leonardo Boff (2000) wrote extensively on how the source of social problems are always theological errors. At a minimum, answers to social questions are codified within religions.

Thus, in a capitalist society—which is based on individual performance, private accumulation of goods, and the predominance of the individual over the social—the representation of God usually accentuates the fact that God is one alone, Lord of all, all-powerful, the source of all power. The usual conclusion is that those who wield power on earth are God’s natural representatives.… In such a context people are unlikely to assimilate the trinitary mystery as a communion of three distinct Persons, who, while distinction is maintained, are, out of love and communion, one sole God (Boff 2000, xi–xii).

Ultimately Boff’s radically trinitarian theology, by him and other Catholic writers in the Global South, led to the development of Liberation Theology. If the great mystery of God is that of relationship, meditation upon that mystery leads to centering the experiences and voices of the poor and other oppressed persons. This insight has, since before the historical appearance of Liberation Theology, inspired Catholic social teaching and action, especially on behalf of the poor. The truth is, many of the insights Boff particularizes within his context were already made in the Franciscan tradition of Boff by St. Bonaventure (1217–1274), for whom the Trinity is a sign that every person, every part of created nature, reflects God.[16] A Catholic, who takes Trinitarian theology seriously may or may not accept the insights of Liberation Theology, but they also are not free to escape into the belly-gazing of Platonic theology, denying the reality of God as relationship. Just as God is Beauty/Beautying, and God is Goodness, and God is Truth, God is Love.

What is the mission of Music Education?

The mission of music education has been, and is, the cultivation of vir perfectus, though the virtues being taught has changed with the values of the societies over those centuries (See Figure 4: Music Education’s Vir Perfectus). To exemplify, Gustafson (2015) analyzed comportment, the teaching of bearing and behavior, through Music Education as an embodied educational ritual in the student-teacher relationship. The contemporary virtues of the vir perfectus would include the medieval virtues of wisdom, prudent speech, handsome appearance, composed gait, upright manners, unspotted life, charity, humility, gentleness, and versatility. For my school district, virtues of adaptability, resilience, productivity, and moral character; and for praxial music educators, tolerance, curiosity, respectfulness, conserving toward society, and gratefulness. Some of the specific virtues emphasized may vary, depending on where a teacher teaches, but that there is a conception of vir perfectus in modern Music Education seems clear. All children must be music educated, so that all may grow toward that perfect ideal.

Figure 4: Music Education’s Vir Perfectus.[17]

Inherent to the new vir perfectus—the perfect life—is that from what students are being saved—from the imperfect life. The imperfect life would be defined in converse to the virtues outlined. For instance, students are being saved from the unwise, imprudent, uncomposed, uncharitable, arrogant, uncompromising, immoral, narrow-minded, disrespectful, and ingrateful life. But one virtue, not yet mentioned, outweighs all others in the ritual of schooling in Pennsylvania public schools: Compliance.

The PSSAs as a Religious Ritual

Some of the rituals and myths of Music Education are shared by all educators—but as Music Educators we experience these in distinctive ways. For instance, all children in my school take the Pennsylvania System of School Assessment (PSSA) exams. The rationale, persistence, and ceremonies of these high-stakes exams are utilitarian—they are presented as being of use in some ambiguous and overbearing way. Myths are traditional and symbolic stories that are able reveal something as true, in some way. Consider, for instance, the myths of Prometheus, who stole fire from the Greek gods and was punished severely, echoing the story of Adam and Eve taking from the tree of knowledge and being expelled from the garden of delight. Both tell some truth of the links between increased knowledge and suffering.

The PSSAs serve as a good example of what myths are perpetuated in schools, whether music continued to be a school subject or not. The rationale for the PSSAs is circular, like a serpent biting its own tail: a “standards-based, criterion-referenced assessment which provides an understanding of student and school performance related to the attainment of proficiency of the academic standards.”[18] The standards provide utilitarian rationale for standards—there’s a reason why I claim at the onset this sort of utilitarianism fails to be a philosophy. We expect more of philosophies than circular reasoning. As such, following Bowman’s analysis of Music Education (as cited in Mark 2002), they essentialize The Academic Standards. Perhaps, if utilitarianism were required to submit a philosophical rationale, standards-based assessments would need to be universally instituted to attain standard proficiency, but then they would need to point toward some other human virtue—something other than compliance to standards to teach standards. English Language Arts, Mathematics, and Science and Technology are the three areas of human existence codified as tested disciplines, but the ritual of taking this high-stakes exam affect the entire school, effects which begin long before the test it taken, and repercussions which reverberate through the end of the school year and beyond.

Historically, the PSSAs were developed in 1992 by a testing company in New Jersey, and are, since 2013, delivered to all Pennsylvania public school students between the grades of three and eight. High School students take a different standardized test, the Keystone Exam. These tests gradually transmogrified into their current form. In 1992, the tests were administered, in a much smaller form on a three-year cycle, and by 1999 Pennsylvania Academic Standards began publishing standards for Reading, Writing, Speaking and Listening, and Mathematics, the guiding standards of its post-2001[19] No Child Left Behind transformation, and escalation in weight.[20] The PSSAs are owned and written by Pearson Education, a subsidiary of Pearson plc, a multinational corporation headquartered in London, England. Over the decades Pearson’s focus has been on civil engineering (1844–1925), manufacturing (1856–1993), electricity (1900–1960), oil (1901–1989), banking and financial services (1919–1999), coal (1921–1947), publishing (1921–1997), aviation (1929–1959), entertainment media (1981–2002), and education (1998–date). The primary concerns around Pearson have been around its influence on public education, tax avoidance, its attainment of high value contracts, and laying off teachers to offset the high cost of testing.[21] This year, neither pedagogy nor curriculum in Music Education was modified by the PSSAs. Curriculum and instruction in tested subjects have been transformed, for decades, as schools are motivated to teach-to-the-test, often using teaching scripts, superseding any other educational theory or ideals within the disciplines.

In addition to PSSA training, required training for all teachers in Pennsylvania, I had to post my yearly certificate on the hallway, a ritual that proclaims the legitimacy of this testing system over each teacher to every student and community member who enters the building. During six days of school-wide implementation of the PSSAs themselves, I was given two occupations: 1. I would accompany every student in the fifth and sixth grade (approximately ages ten to eleven) hallways to the restroom to ensure they did not talk about the test; and travel to each classroom in the second and third hours of testing to offer each classroom teacher/proctor a restroom break. As I accompanied a fifth grader to the restroom, he said to me, “This feels like prison.” I agreed but continued to serve my function in this ritual—itself an act that legitimizes the PSSAs.

This year, students had many challenges connected to the testing technology itself, which did not reach our field’s standards of conviviality (Bates and Shevock 2020; Shevock and Holster 2025). Each student is issued a “ticket” to access the correct test. During one day of testing, sixth grade students discovered the computer system turned on all accommodations, normally only available to students with explicit Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) that permit accommodations. The following day of testing was postponed for that grade-level as the school awaited a ruling on whether they would need to retake that day’s test. Every class had at least one student, and one entire fifth grade classroom, who during the course the test implementation, could not access the test itself; and these access problems were usually resolved by resetting the computer, or issuing the student a new ticket. Each instance required input from the district’s IT department, which was juggling instances throughout the district.

What myths do the PSSAs perpetuate? The first, and dominant myth perpetuated by the PSSAs as a ritual is compliance. Not only do they observe, weekly throughout the school year, teachers of tested subjects complying to read scripts and teach test-specific lessons, but throughout the tests themselves, they see administrators complying to their roles in touting the test’s importance, and all teachers in fulfilling their roles during the exam in proctoring, monitoring, and disciplining non-compliant students. Secondly, students learn that technological change is unavoidable and cannot be resisted. Even though most teachers agreed returning to paper testing would be more efficient, the decision to use only these buggy and inconsistent computer systems was decided at the district level and will be required throughout the Commonwealth by 2026.[22] As Bates and Shevock (2020) recommend, technologies ought to be adopted when they promote community, the commons, and conviviality—serve humane ends, avoid waste, promote communication and intercultural understanding, are dependable and noncoercive. The technology used failed on all points. The restroom policy that is taught at the state-level by the PSSA training system, was the fruit of a system that demands unquestioning compliance from start to finish. While the PSSAs do not test music, the PSSAs are a dominant thing music teachers and students do. As such, the utilitarian vir perfectus is compliant, and little else.

Similarly, perpetuating compliance as an ideal within the PSSA testing regime, the rituals within music classes in general music, band, orchestra, and choir perpetuate many myths, which have been shared in countless articles and books (e.g., Benedict 2012). These include the myth that this specific music is for all, will lead to economic success, and will make people better through a process of becoming more cultured. Additionally, praxial Music Education ritualizes the musics of various cultures, promoting diversity, but not always the type of diversity that sustains the other. Too often it is a diversity of accumulation by the Global North of musics, people, history, cultures, and languages of the Global South; the bourgeois of the proletariat; and the urbane of rural musical cultures. For Music Educators guided by aesthetic theory, these rituals perpetuate music as something transcendent in an ossified but entirely psychological way, and that Western Classical Music holds an especially transcendent place.

What is Religion, then?

Do music and religion sharing a common root, as Reimer suggested, mean music, or Music Education, is religion? There is a gulf between “is” and “is like,” which makes this analysis a challenge. However, it is possible to bring some clarity, if not conclusion to the question. Religion can be understood as “human beings’ relation to that which they regard as holy, sacred, absolute, spiritual, divine, or worthy of especial reference.”[23] Religions offer ways for people to understand fate and manage feelings about death; experience a relationship with deity(ies); and guides a person’s attitude toward other people and nature. Religions can have hallowed writings, and devotional practices such as prayer, meditation, saints, and music. According to a Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy article, religions, in historic context, have to do with the following:

- Scrupulousness (thoroughness)

- Conscientiousness (carefulness)

- Devotedness (devotion)

- Obligations (duties)

- Taboos (prohibitions)

- Promises (guarantees)

- Curses (blasphemies)

- Transgressions (offenses)[24]

These eight points (and the five points of Herbert below) make up various ways to define religion. These are each outward expressions of religion, and as such offer identifiable markers. Outward expressions of religion are important but not encompassing of religion. For many people participating in a religion, outward expressions are the greatest part of religion—how one does religion is how one is religious. For others, psychological and spiritual aspects are centered—external obligations and promises are important, but faith, or spiritual growth, or relationship is greater. Both are at play within the Catholic intellectual tradition. In the apostle Paul, internal faith takes precedent: “By faith we understand that the universe was ordered by the word of God, so that what is visible came into being through the invisible” (Hebrews 11:2, NABRE); and James gives outward expressions of religion primacy: “What good is it, my brothers, if someone says he has faith but does not have works? Can that faith save him? … So also, faith of itself, if it does not have works, is dead” (James 11:14, 17, NABRE). For those whose religious convictions are more Jamesian, these eight points serve well; and for those who are Paulist, Herbert’s five points may seem more accurate in defining religion. Both definitions are offered for readers.

Defined as simply as these eight points, Music Education can be understood as being a religion. Music teachers (and priests, shamans, pastors, rabbis, and various religious leaders) are thorough, careful, and devoted to their subject enough to feel an obligation to advocate for it. Music teachers also act on other duties, such as teaching a classical cannon, delivering instruction in technique and scales, and responding to students’ interests; as well as avoiding taboos, such as holding the violin bow incorrectly, or singing with a belting voice. And music teachers make students promises of future success. There are those who blaspheme against the dominant music educational system, and their transgressions are often noted and avoided by other music teachers. But all these outer signs of religions, in historical context, seem to miss something important about religion. The Catholicism with which I am so familiar is ultimately about the nature of God and our human relationships with Him and each other. This seems irreducible to the eight activities outlined above.

In the same article, Edward Herbert (1583–1648) identified five elements found in every religion:

- There is a supreme deity

- This deity should be worshipped

- The most important part of religious practice is the cultivation of virtue

- One should seek repentance for wrong-doing, and

- One is rewarded or punished in this life or the next.

These common notions of religion seem to connect more with what is commonly held to be religion. Music Education, as a professional field, does not fare so well as a religion in reference to these five elements. It makes no statement about a supreme deity, or whether it should be worshipped. The other three elements are not great fits, but may be re-construed to fit into the context of education, but reading these elements, I would conclude Music Education is seemingly not a religion. This is a very practical point—religions are about God, or Goddess, or gods. Sharing some similarities with religion, we might do well to explore what, if Music Education were a religion, our field’s historical turn would involve. I’m not saying that the historical turn is religion—I feel the historical turn is toward an ecological philosophy that synthesizes in some way praxial and aesthetic philosophies, suggested elsewhere (see Shevock 2015, 2017; Shorner-Johnson and Shevock 2020)—but that since the ecological philosophy that represents the current turn in our field dwells in the interconnections among unexpected realms of living, religions (etymologically, ligaments as of a body) might direct our attention toward something we have not seen. What are religions doing now, theologically.

Some religions have developed explicit ecotheological statements, many others have increasingly felt the need to cultivate them. For many Christians, as Heather Eaton (n.d.) describes, this has been a decades-long effort, in many traditions. While ecotheology has become prominent in universities, seminaries, and parishes, Eaton describes challenges (and contributions) including internal beliefs, such as scriptural sufficiency and inerrancy, archaic dogma, understandings of creation stories, the variety of ecological concerns, and Christianity’s role in colonialism, extractive consumption, emissions, and deforestation.

Music Education shares many similarities with religion but differs in critical ways. Similarities may include our role in colonialism, extractive consumption, and deforestation. The differences may be understood as enough to not define Music Education as a religion. However, Music Education’s other similarities to religion—in having revered texts, relating the human to the absolute and divine, having a salvific mission, its prescriptions for guiding our field’s attitude toward other people and nature—provide not only insight into the possibility of a Music Education theology, but also the seeming religious-like commandments of aesthetic and praxial philosophies. Music Education is often shaped by religion; and, through historical analysis, I aimed to understand the nature of the link between Music Education and religion. A third emerging philosophy, the ecological, also offers religious-like prescriptions, though the differences in mission and mythmaking, to the previous two philosophies, offer increased straightforwardness and helpfulness in addressing the ecotheological inclination that all religions feel in the twenty first century.

The way forward for our field, then, is not found in aesthetic theory, which tends to become Platonic. Neither is it necessarily in the dominant conceptions of praxial Music Education, but in an ecological praxis, a praxis of relationships among humans, animals, and nature (see also Shorner-Johnson, Gonzalez, and Shevock 2023). The ecological approach can help cultivate additional virtues, such as community and intradependence (Bates 2013), and a sense of wonder. Because an ecological music education is interdisciplinary and experiential, it helps cultivate sense of wonder[25] in nature (Matsunobu 2017; Smith 2021). Wonder can, as expressed by Tawnya Smith, mend mental health, and attune children to their “soul’s purpose” (9). Additionally, the ecological perspective, when paired with songwriting, can be used to open space for a “courageous fight for climate justice” (Eustebrock 2022, 397). This critical consciousness can help students overcome the psychological trials related to facing ecological crises.

MUSIC ≠ RELIGION … Or does it?

For some people, Music Education, then, might be considered a material and transcendental concept held entirely within the scope of religion. But religions offer something beyond the self. A transcendent conception that is entirely between the ears does not appear to be offering a transcendence consistent with religious transcendence—but can be a position held by those who already have a conception of immaterial realities beyond the realm of Music Education. For us, both sacred and secular songs, as well as dances of various cultures, playing instruments, place-conscious ethics, storytelling, and everything else involved in guiding young folk musically is in some ways religious, and fits within God’s plan for humans living and growing in loving relationship with one another. Religious experience is, so to say, the whole of existence, and Music Education is one thing people, and some other species including birds and whales, do.

But for others, Music Education does not lie within the scope of religion as many folks do not believe in religion at all. Confessing the soundness of one’s religious experience does not affect being condemnatory of others. As condemnatory statements separate us from one another, religious confessions, to be religious, connect and do not dissect people from one another—religion means cultivating relationships. Further, who would judge anybody who has made the decision to avoid participation in a religious community in the wake of Covid; or before that because of the Great Recession, the Patriot Act, 9/11, Columbine, Heaven’s Gate, the Matthew Shepherd slaying, the child-abuse scandals, the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and the eldest Japanese Catholic community in Nagasaki by a Catholic pilot; or an accumulation of these and other disenchanting events associated with religious traditions. However, for Christians, scripture explicitly challenges us to speak to more than spiritual realm dissected from the material.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church states:

- God created the visible world in all its richness, diversity, and order.

- Nothing exists that does not owe its existence to God the Creator.

- Each creature possesses its own particular goodness and perfection.

- God wills the interdependence of creatures.

- The order and harmony of the created world results from the diversity of beings and from the relationships which exist among them.

- There is a solidarity among all creatures arising from the fact that all have the same Creator and all are ordered to his glory. (John Paul II 1995, 98–99)

I chose to highlight these points from the Catechism of the Catholic Church because the Catechism contains the rules Catholics ought to hold and exemplify what I have been arguing is an ecological philosophy. As such, there are 1.39 billion people on this planet who are called to celebrate diversity, the particularity of each creature’s goodness, harmony, solidarity and interdependence. This, to my understanding, is the ecological position in short. This ecological philosophy is not coming out of a theologian on the edges of the tradition, such as when Leonardo Boff and Thomas Berry were first writing ecotheologies; and not even in a papal encyclical with flexible applicability but is set at the core of this tradition—the Catechism.

All religions are, in the twenty first century, by awareness of the realities of ecological destruction called to make explicit ecotheological statements. Music Education can support the overarching goals of religion by also supporting more ecological understandings that emphasize the virtues and goodness of non-human creatures, and harmony of interdependence among our teaching practices for a more sustainable world. This is the work begun by me, Vincent Bates, Tawnya Smith, June Boyce Tillman, Linus Eusterbrock, and other scholars working on ecological Music Education theory, philosophy, and sociology (see Bates 2013; Boyce-Tillman 2004; Eusterbrock 2022; Foster and Sutela 2024; Guo, Su and Yue 2020; Jorritsma 2021; Juntunen and Partti 2022; Lafontant 2019; Matsunobu 2017; Schuurman-Olson 2023; Smith 2021). But, even with the expansion of Music Education toward being more relevant to the full material and transcendent universe of relationship, the scope of Music Education is a humble part of that universe, and we cannot change the world alone. In this sense, it seems Music Education is NOT a religion. Religions change the world, as well as changing Music Education philosophy and praxis.

There are clearly important aspects of human experience for which Music Education does not attempt to wrestle. To exemplify, the Catholic Practice of momento mori,[26] contemplating one’s death—especially noticeable in the rosary, which involves repeating “now and at the hour of our death,” 153 times, within the context of the Ave helps people struggle with the inescapable fact that we are alive now, but we will certainly die. Every one of us will die. Salvation from death is the way of Christianity. The Catholic mass, a weekly obligation, is a ritual remembrance of the passion, death, and resurrection of Jesus. And a fundamental theme of the Gospels and creeds we recite each mass is the resurrection of, not merely the soul, but also the material body. Without any grappling with the mystery of living and dying, with which all human persons must struggle. Although, as teachers, we give our lives to this profession in meaningful ways, and this can parallel a sort of dying, I cannot see any claims to Music Education being a religion being fully true. Future research from the Catholic perspective can look at Beauty and Music Education from a Thomist perspective, or from the Augustinian tradition. These intellectual dynamos have dominated Catholic religious discourse for centuries. Perhaps I ought to have been able to draw more on the Thomist tradition in specific, as Ivan Illich was a student of the Thomist Jaques Maritain, and Thomas Berry is explicitly Thomist in his ecotheological writings—and both these scholars influence my work. However, I find myself drawn toward the Franciscan tradition, which, to me, seems to more humbly draw from both these doctors of the church and their intellectual descendants in the academy today in earthy, practical ways.

Religion offers myths that help us to handle the most difficult situations in life—those rife with ambiguity. Perhaps this is where we can say, with more assurance, Music Education is NOT a religion. It just does not do what we need done. It does not offer that degree of meaning since Music Education does not posit an extra-material existence. Religious stories and symbolism help us encounter real life experiences and emotion in a way Music Education does not.

However, maybe I am underestimating the power of Music Education as a meaning-making tool, especially in relation to experienced sadness. My mind turns to Mary Cohen’s research with songwriting in a medium security prison. She shares a song, “May the Stars Remember Your Name,” in which a songwriter laments the hiddenness of stars, communicating “longing to see the stars in the night sky [that are] not visible due to bright security lights surrounding the prison” (Cohen and Wilson 2017, 545). This instance seems to obtain a degree of meaning-making associated with religious experience.

Maybe this meaning-making is not specific to Music Education, but musicking in general (See Small 1998). To distinguish, Music Education is a profession that includes musicking, a social ritual, that is broader in scope, but not inclusive of everything involved in Music Education. “May the Stars Remember Your Name” does not require anything beyond the experiencer’s brain—the meaning affected here is not automatically or necessarily transcendent. It seems clear though, when reflecting on it, deep psychological experience is not the same thing as religious experience. Religious experience is, whether real or delusional, about something external to oneself, and psychological experience, even if illusive and unexplainable, is internal—within the brain.

Musicking can be, or at least has the potential to be, a meaning-making tool when we are facing the worse emotional moments in life. It offers some consolation. Music has been part of the religious experience and, even separated from it, speaks to the human soul in a similar way. Different but similar. And yet, talking about music as separate from religion is a very modern endeavor. Throughout history musicking has been a tool of culture, that is, one part of the cult, or religion of a community. To the extent that music serves the stories and ritual of religion, music is profound for people, because, to an extent, it is religion in some of the same ways that a branch is a tree, and the skin is the person. One particle of light on a broken shard of glass—one part of transcendent beauty is, in some way, transcendent Beautying.

About the Author

Appalachian music education philosopher, Daniel J. Shevock’s scholarship blends music ecology, ecotheology, and creativity. He is the author of two monographs published by Routledge, Eco-Literate Music Pedagogy (2017) and Music Lessons for a Living Planet: Ecomusicology for Young People (2025) with Vincent Bates, many peer-reviewed articles, chapters in edited books, a YouTube channel, and a blog at eco-literate.com. He earned degrees from Clarion University of Pennsylvania (BSEd 1997), Towson University (MS 2000), and Penn State (PhD 2015), and has taught students from pre-kindergarten to university levels in Maryland and Pennsylvania (USA). Dan is currently a middle school general music teacher (Grades 5–8) with the rural Keystone Central School District in PA and is a hiker, jogger, vegetarian, and gardener.

References

Aleghieri, Dante. 1997. The divine comedy. Translated by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Project Gutenberg eBook. (Original work published 1472.) https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1001/1001-h/1001-h.htm

Bates, Vincent C. 2005. Moral concepts in the philosophy of music education. PhD diss., University of Arizona.

Bates, Vincent C. 2016. Big city, turn me loose and set me free. A critique of music education as urbanormative. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 15 (4): 161–77. https://doi.org/10.22176/act15.4.161

Bates, Vincent C. 2013. Drawing from rural ideals for sustainable school music. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 12 (1): 24–46.

Bates, Vincent C, and Daniel J. Shevock. 2020. The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly of social media in music education. In The Oxford handbook of social media and music learning, edited by Janice L. Waldron, Stephanie Horsley and Kari K. Veblen, 619–44. Oxford University Press.

Benedict, Cathy. 2012. The social contract and music education: The emergence of political authority. Revista da Abem 20 (27): 11–20.

Benedict XVI. 2010. Message of his holiness Pope Benedict XVI for the celebration of World Day of Peace. https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/messages/peace/documents/hf_ben-xvi_mes_20091208_xliii-world-day-peace.html

Boff, Leonardo. 2000. Holy trinity, perfect community. Orbis Books. (originally published 1988 as Santíssima Trindade é a melhor communidade)

Bowman, Wayne D. 1994. Sound, society, and music proper. Philosophy of Music Education Review 2 (1): 14–24.

Boyce-Tillman, June. 2004. Towards an ecology of music education. Philosophy of Music Education Review 12 (2): 102–25.

Boyce-Tillman, June. 2013. And still I wander… A look at Western Music Education through Greek mythology. Music Educators Journal 99 (3): 29–33.

Catholic Answers Staff. n.d. Q&A: When did the term “Roman Catholic Church” first come into being? https://www.catholic.com/qa/when-did-the-term-roman-catholic-church-first-come-into-being

Cohen, Mary L. and Catherine M. Wilson. 2017. Inside the fences: Pedagogical practices and purposes of songwriting in an adult male U.S. state prison. International Journal of Music Education 35 (4): 541–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761416689841

Day, Dorothy. 2017. The reckless way of love: Notes of following Jesus. Plough Publishing House.

Eton, Heather. n.d. Overview essay: Christianity and ecology. Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology. https://fore.yale.edu/World-Religions/Christianity/Overview-Essay

Eusterbrock, Linus. 2022. Climate-conscious popular music education: Theory and practice. Journal of Popular Music Education 6 (3): 385–401. https:// doi.org/10.1386/jpme_00098_1

Foster, Raisa, and Katja Sutela. 2024. Ecosocial approach to music education. Music Education Research 26 (2): 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2024.2319586

Francis. 2015. Laudato Si’: On care for our common home. https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si.html

Guo, Minjian, Hua Su and Lei Yue. 2020. Ecology-focused aesthetic music education as a foundation of sustainable development culture. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 45 (4): 564–80.

Gustafson, Ruth. 2015. Fictions of the transcendent and the making of value in music education in the United States. In The “reason” of schooling: Historicizing curriculum studies, pedagogy, and teacher education, edited by Thomas S. Pokewitz, 215–28. Routledge.

Hellwig, Monika K. 2000. The Catholic intellectual tradition in the Catholic university. In Examining the Catholic intellectual tradition, edited by Anthony J. Cernera and Oliver J. Morgan, 1–18. Sacred Heart University Press. https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1015&context=shupress_bks

Illich, Ivan. 2012. Celebration of awareness: A call for institutional reform. Marion Boyars.

Illich, Ivan. 1978. Toward a history of needs. Pantheon Books.

Jaeger, C. Stephen. 1994. The envy of angels: Cathedral schools and social ideals in medieval Europe, 950–1200. University of Pennsylvania Press.

John Paul II. 1995. Catechism of the Catholic Church. 2nd ed. Doubleday.

Jorritsma, Marie. 2021. Towards an eco-literate tertiary music education: Notes from a South African context. International Journal of Music Education 40 (1): 1–12.

Juntunen, Marja-Leena, and Heidi Partti. 2022. Towards transformative global citizenship through interdisciplinary arts education. International Journal of Education & the Arts 23 (13): 1–28.

Lafontant Di Niscia, Attilio. 2019. Unveiling the dark side of tonewoods: A case study about the musical instrument demand for the Venezuelan youth orchestra El Sistema. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 8 (3): 258–88. http://doi.org/10.22176/act18.3.259

Mark, Michael L., ed. 2002. Music education: Source readings from ancient Greece to today. 2nd ed. Routledge.

Matsunobu, Koji. 2017, July. Ecomusicality: An ecological pedagogy of music. Paper presented at the Asia-Pacific Symposium for Music Education Research, Melaka, Malaysia.

Mayers, Coral. 2008, January 25. PSSA information. http://pssablog.blogspot.com/2008/01/pssa-pennsylvania-system-of- school.html.

Merton, Thomas, ed. 1965. Gandhi on non-violence. New Directions.

O’Neill, Terry. 2022. Anti-Catholic hate crimes rising faster than every category combined, and few seem to care. The B.C. Catholic. https://bccatholic.ca/news/catholic-van/anti-catholic-hate-crimes-rising-faster-than-every-category-combined-and-few-seem-to-care

Plato. 1998. The republic. Translated by Benjamin Jowett. Project Gutenberg eBook. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1497/1497-h/1497-h.htm

Prakash, Madhu Suri, and Gustavo Esteva. 2008. Escaping education: Living as learning within grassroots cultures. Peter Lang.

Regelski, Thomas A. 2020. Tractate on critical theory and praxis: Implications for professionalizing Music Education. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 19 (1): 6–53. https://doi.org/10.22176/act19.1.6

Reimer, Bennett. 1963. The common dimensions of aesthetic and religious experience. EdD diss., University of Illinois.

Schuurman-Olson, Stephanie. 2023. Singing in the dark: Seeking connection in a time of climate crisis. Canadian Music Education 2023 (50): 34–41.

Shevock, Daniel J. 2015. Satis Coleman—A spiritual philosophy for Music Education. Music Educators Journal 102 (1): 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432115590182

Shevock, Daniel J. 2017. Eco-literate music pedagogy. Routledge

Shevock, Daniel J. and Vincent C. Bates. 2019. A music educators guide to saving the planet. Music Educators Journal 19 (1): 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432119843318

Shevock, Daniel J. and Vincent C. Bates. 2025. Music lessons for a living planet: Ecomusicology for young people. Routledge.

Shorner-Johnson, Kevin (host) and Daniel J. Shevock. 2020, January 3. Season 1, Episode 11: Musicking ecological care and rootedness. Music & Peacebuilding Podcast. https://www.musicpeacebuilding.com/ep11-musickingecosystems

Shorner-Johnson, Kevin, Martha Gonzalez and Daniel J. Shevock. 2023 Convivencias and a web of care. In The Oxford handbook of care in music education, edited by Karin S. Hendricks, 69–78. Oxford University Press.

Small, Christopher. 1998. Musicking: The meanings of performing and listening. Wesleyan University Press.

Smith, Tawnya D. 2021. Music education for surviving and thriving: Cultivating children’s wonder, senses, emotional wellbeing, and wild nature as a means to discover and fulfill their life’s purpose. Frontiers in Education 6: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.648799

Taylor, Jerome, trans. 1961. The didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor. Columbia University Press. https://archive.org/details/didascaliconmedi00hugh/page/n17/mode/2up

Wojtyla, Karol (John Paul II). 2021. God is beauty: A retreat on the gospel and art. TOBI Press.

Yob, Iris, M. 2011. If we knew what spirituality was, we would teach for it. Music Educators Journal 98 (2): 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432111425959

[1] Gandhi taught, “No [person], if [they are] pure, has anything more precious to give than [their] life.” This quote comes from a volume edited by the 20th Century mystic, Thomas Merton (1965, 48). Gandhi was influenced by Christianity, the Beatitudes in particular, and had also an effect, in turn, on the Catholic intellectual tradition.

[2] Link: https://www.etymonline.com/word/humility.

[3] Throughout this paper is use the capitalized Music Education to refer to the profession, with special attention to Music Education as a professionalized music teaching and learning experience, especially but not exclusively occurring in public, private, and parochial schools. In this way, Music Education is a noun, a profession, and essentialized in the same way aesthetic theorists essentialize music. In contrast, musicking is a verb, and is merely the doing of music—what is often referred to as music-making by aesthetic Music Education theorists, but musicking by praxialists.

[4] To exemplify, Regelski (2020) describes methodolatry as “an almost religious or cult-like attachment to particular ‘techniques,’ ‘methods’ or ‘materials’ of teaching” (16) and a “religious faith in method” (23); and in education, Illich (discussed in this paper) and Prakash and Esteva (2008) call education a religion.

[5] In the U.S. Creating and Performing/Presenting/Producing standards can especially be seen as praxial, while responding is often institutionalized within the context of aesthetic response. Link: https://www.nationalartsstandards.org/

[6] As such, I will be referencing Mark (2002), especially pages 27-29, as well as articles on contemporary music education figures.

[7] Link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medieval_technology.

[8] The first branch included the liberal arts, the second religious studies. To illustrate the goals of early medieval education, St. Sturmi of Fulda was an eighth Century teacher. St. Sturmi was a Benedictine abbot and a student of St. Boniface. In 774, his abbey received protection from Charlemagne. His educational theory involved cultivating the vir perfectus—the perfect person.

[9] Link: https://www.kcsd.us/our-district.

[10] Following this line of thinking then, I might suggest the moral lessons of life are within the religious—the religious being equivalent in many ways to the idea of the political within a secular context. Church and State offer a traditional pairing of two bodies of power in society—one with power over the spiritual life and the other over the material life—for those who accept this distinction. This is not an argument against materialism, per se, but rather an argument for those who agree from the outset that there are material aspects to life, such as soundwaves, trees, stars, compost; and, alternatively, there are non-material aspects to life, such as truth, goodness, and beauty. Not that truth, goodness, and beauty fail to have material aspects, but that there are non-material aspects of them. An immaterial/spiritual essence, so to say.

[11] I have previously called this every day, soiled, multifaceted philosophical stance postmodern—but I’ve come to believe that term has gathered too much baggage, rejecting itself the possibility of any reality beneath the surface, and of any meaning-making—where my previous understanding of postmodern involved challenging metanarratives, which I still do. To the extent that “postmodern” accepts the possibility of such an underlying Truth, but inspires ongoing critique and skepticism toward it, my current stance might still be considered postmodern. But to the extent that postmodernism makes an essence of an underlying Untruth or No-Truth, then my current stance cannot reasonably be called postmodern.

[13] An Illustration of The Allegory of the Cave from Plato’s Republic. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:An_Illustration_of_The_Allegory_of_the_Cave,_from_Plato%E2%80%99s_Republic.jpg

[14] Canticle of brother sun and sister moon of St. Francis of Assisi. https://ignatiansolidarity.net/blog/2015/06/04/canticle-of-brother-sun-and-sister-moon-of-st-francis-of-assisi/

[15] Three best shows their friendship at their bad time. 2012. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:THREE_BEST_FRIENDS.JPG.

[16] See Jonathan Bish. 2020, August 31. Reading Bonaventure in a time of crisis. Earth & Altar. https://earthandaltarmag.com/posts/luz50t8059yazmsw1ataiotc5ppdfw

[17] Modified from Fairbanks, 1907 The Perfect Man. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 70 years or fewer. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fairbanks_The_Perfect_Man_(cropped).tif

[18]https://www.education.pa.gov/K12/Assessment%20and%20Accountability/PSSA/Pages/default.aspx