VINCENT C. BATES, DEBORAH BRADLEY, and J. SCOTT GOBLE

Guest Editors

November 2025

Published in Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 24 (6): 1–21 [pdf]. https://doi.org/10.22176/act24.6.1

Abstract: Thomas A. Regelski, who created this journal—Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education—and co-founded the MayDay Group, died one year ago. We are pleased to present this special issue of ACT in his memory. All three guest editors previously served as editors for this journal and worked closely with Tom in this and other capacities. We each have an abiding respect for his contributions to the academic field of school music education. In this editorial, we highlight the ongoing importance of Tom’s writing and organizing. We also consider relevant reinterpretations, extensions, and applications of his academic output, including concepts associated with Critical Theory, aesthetic experience, neoliberalism, anti-racism, pragmatist philosophy, ethnomusicology, and musicology. Finally, we introduce and contextualize the other four articles within this issue.

Keywords: Thomas A. Regelski, critical theory, fascism, aesthetic experience, neoliberalism, social justice, anti-racism, pragmatism, ethnomusicology

Tom Regelski’s professional work in the field of school music education is perhaps more relevant now, one year after his death, than it ever was. Tom introduced, promoted, and embodied Critical Theory in a field perennially troubled by legitimacy crises, preoccupied with aesthetics-based advocacy, and rife with taken-for-granted assumptions about the nature and value of music in schools. In addition to highlighting what makes music and music education so wonderfully necessary and welcome in compulsory education, Tom stressed the urgent need for change; music education was not fully meeting the needs of young people, musically or otherwise, currently or long-term. Taken-for-granted assumptions about music, teaching, and learning upheld malpractice (malpraxis) to the extent that music education might in some instances bring about more harm than good.

At first glance, this type of direct criticism may seem overly negative and counterproductive, but we maintain, as Tom did, that it is an essential step to improving practice, ensuring that school music education brings about positive results for all people, equally and on their own terms. This is Tom Regelski’s professional legacy: the extent to which his writing, the ACT journal, and the MayDay Group have influenced the thoughts and actions of so many to think more critically about school music education and to forge practices better attuned to phronesis—an ethic of care. There is still a long way to go. In this introduction to a special memorial issue of ACT, we argue for the prescience of Tom Regelski’s scholarly work, outline important extensions of his critical theorizing, and introduce and contextualize the articles within this issue.

Critical Theory

We imagine that most ACT readers, like us and to varying degrees, feel daily the weight of neoliberalism, now metastasizing into fascism. On the other hand, we also anticipate that some will think that this is an exaggeration—that things aren’t all that dire and/or that it is better to think positively and perhaps to “think only about teaching music.” Such aversions to critical thinking seem incongruous in a field otherwise centered on criticism; it is especially ironic when school music ensemble directors whose careers are spent pointing out what’s wrong in music performances and striving for the most effective and lasting corrections can so easily be offended when it comes to criticism of their own work and profession.

Regarding neoliberalism and fascism, we are not exaggerating; criticism is more urgent, and the stakes are higher now than ever. It should give everyone pause, for example, that in some of our institutions of higher learning, employees are no longer allowed to write or utter words that used to be commonplace in academia (i.e., diversity, equity, and inclusion). To invite further consideration of how alarming conditions have become overall, we invite readers to ponder the following qualities of fascism (conveniently generated by AI) in light of the condition and trajectory of the United States, the nation with arguably the world’s largest economy and, in the neoliberal present, arguably still the most influential nation on earth.

While no single, universally agreed-upon definition exists, fascist movements typically share several key traits:

- Authoritarian and totalitarian rule: Power is centralized in a single leader or a small elite, with no room for political dissent.

- Militarism and nationalism: The ideology aggressively promotes national pride and identity, often through militaristic displays and contempt for other nations.

- Rejection of liberal democracy and human rights: Fascism rejects democratic processes and individual rights in favor of the interests of the state.

- Cult of the leader: The leader is portrayed as a heroic and infallible figure who embodies the nation’s will and destiny.

- Controlled economy: While some private ownership remains, the state exercises significant control over economic activity to serve national goals.

- Emphasis on hierarchy: It promotes a belief in natural social hierarchies, where elites are destined to rule, and individuals’ interests are secondary to the nation’s.

- Scapegoating and persecution of minorities: Fascist movements often identify “enemies” within society, using scapegoating and violence to create a sense of national unity.

- Use of propaganda: Fascists control mass media to promote their agenda, glorify violence, and undermine factual truth.

Again, the average music educator might ask: “But what does fascism have to do with music education? I just want to teach kids to sing and to play musical instruments. Can’t we leave politics out of it?” A key insight from Critical Theory is that people are influenced to act against their own interests through the proliferation of various ideologies: dominant ways of thinking and being that are imposed upon and, to varying degrees, accepted by people, often against their own best interests (see Regelski 2020), and that these ideologies can become totalities, pervading every social domain, including the field of music education (for a much earlier discussion of facist ideologies in music education, see Bradley 2009). Rationalities associated with neoliberalism and colonialism—hierarchy, meritocracy, exploitation, militarism, development, competition, accumulation, and an array of associated, identity-based “isms” (classism, racism, sexism, elitism)—can be imposed as default logics within every sub-domain. In the present era, ideology (as defined within Critical Theory) has influenced most people to accept neoliberalism as the natural order of things—it’s the water we swim in, so to speak—and neoliberal ideology now keeps majorities from recognizing and standing up to clear instances of fascism. And, when people fail to think critically, when so much is taken for granted, the inequalities and oppressions that have plagued society for ages are unwittingly reproduced and extended with each new generation.

Consequently, music teachers always teach much more than “just music” whether they intend to or not, and without sufficient critical thought, they run the risk of reinforcing and reproducing humanly and environmentally harmful ideologies.[1] There is no space to which we can retreat that is devoid of politics. Returning to the AI-generated qualities of fascism, it doesn’t take an inordinate amount of critical thinking to recognize congruences between qualities of fascism and standard practices within school music programs in the US and in nations with similar approaches to music education. If we created school music programs to instill dispositions to support fascism, they would likely involve large groups of young people working together, often in competition with other groups, toward common goals under the guidance of strong leaders revered for their benevolence, expertise, and authority. We would encourage young people to trust and obey without question, for the good of the group. We would also organize our programs around musical practices associated with Western culture and colonization to solidify beliefs in the inherent superiority of wealth, whiteness, and patriarchy. “Other” cultures associated with racial diversity and poverty would be denigrated through exclusion, marginalization, or open derision. If our programs could also instill a sense of national devotion and militarism through patriotic music and marching in formation, so much the better. These standard qualities of school music programs, of course, are commonplace in the US and Canada. It may be difficult to imagine school programs more thoroughly suited to fascism than what is already in place.

This is a key argument in Critical Theory, in fact, not that people willfully design such programs of study in support of fascism, neoliberalism, or oligarchy, but that because people abdicate their responsibility to think critically, institutions such as schools evolve in parallel with dominant ideologies, thereby reproducing unequal and oppressive social, political, and economic structures. In this light, Tom called for critical thinking as an essential foundation for professionalism (e.g., Regelski 2009) and decried mindless adherence to method, which he famously referred to as methodolatry (Regelski 2002). Critical Theory can empower people and free them from taken-for-granted assumptions, not only those that plague our field of school music education but also the taken-for-granted assumptions undergirding neoliberalism and fascism. Failing to think critically and/or striving for an ever-elusive political neutrality potentially contributes to maintaining these oppressive social structures. In other words, if music educators are not working to change music education and society for the better (praxis), they are likely contributing to an unhealthy and limiting status quo.

Aesthetics

It is within this framework of Critical Theory and ideology critique that one should understand Regelski’s many “take downs” of aesthetic theorizing. A philosopher might look at aesthetics in the abstract and apply the concept in novel ways (e.g., aesthetics in popular music or in the sounds of nature). Tom saw aesthetic theory as a social construct with deep historical context from which it cannot so easily be extricated or rehabilitated:

In regard to the dominating aesthetic ideology and its educational rationale, it is useful to remember that the closed network of ideas, convictions, beliefs, and habits of an educational ideology can be held so strongly that ‘true believers’ ignore or resist all contrary evidence or arguments and, as a result, fall into malpraxis (i.e., professional malpractice), defensiveness, and a tenacious continuation of the status quo. Those teachers who, as a result of their university socialization, accept and defend the belief that the aesthetic ideology for musical value is an effective basis for school music—despite its lack of lifelong legacy for graduates and other social problems—thus continue with this institutional ideology to the detriment of their social responsibilities as a “helping profession.” (Regelski 2016, 25).

Some have argued that the critique of aesthetic theory is no longer relevant, that we have moved on as a profession from the aesthetic versus praxial philosophical debates of the 1990s. Reviewing some of Tom’s writings, Roger Mantie (2016), for example, suggested: “The constant labeling of good teaching as ‘praxial’ and bad teaching as ‘aesthetic’ … seems to dilute the message, and may be confusing for younger readers not acquainted with the acrimonious aesthetic versus praxial battles of years past. Perhaps it is time to move on from such reductionist labels and concentrate on more timely and important issues” (216). Others have similarly suggested that Tom’s definition for aesthetic experience was too narrow (e.g., Westerlund 2003). In these instances, both of which appeared in the Philosophy of Music Education Review, there might be some confusion about the various roles of philosophy and sociology. Critical Theory is both philosophical and sociological. Tom’s discussions of aesthetic ideology derived from a thorough look at the history of aesthetic terminologies and concepts within the history of Western culture. He wasn’t so much arguing about what aesthetic education could or ought to be but what it had become in the field of music, and how it was an inextricable part of Western classical music along with all its highbrow baggage (e.g., Regelski 2006, 2007, 2011, 2016). Western classical music—music predominantly by white males of European descent composed for the aristocracy and other elite groups—was seen, via aesthetic theorizing, as superior to all other kinds of music. So, even though Tom did not write much about social justice, this type of sociological critique was still integral to subsequent social justice narratives in music education.

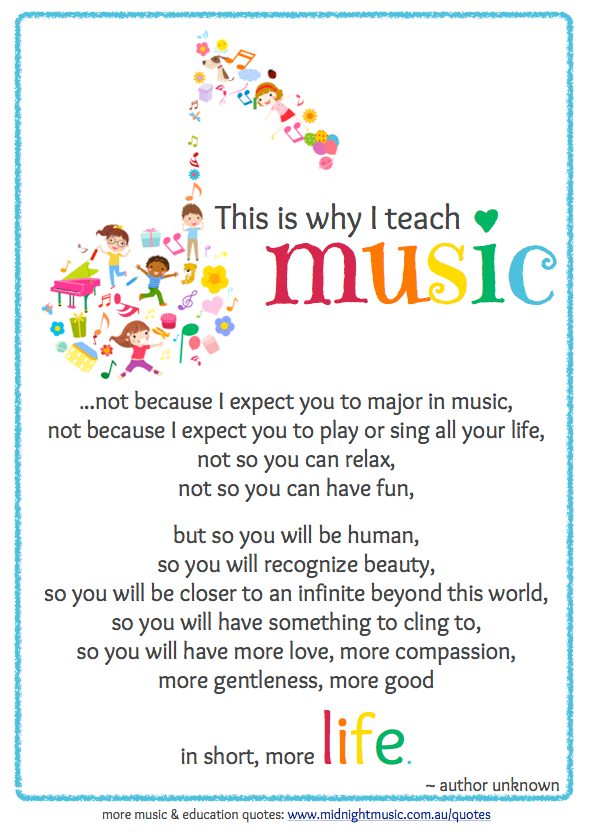

In addition, Mantie’s idea that, as a profession, we have somehow moved past the praxial vs. aesthetic debates may be missing some relevant context. Often scholarly discourse progresses beyond what is really happening in the field, and this may be a case in point. While the debate might strike some academics as passé, aesthetic theorizing is still a huge part of school music education. It is difficult if not impossible to emphasize or privilege classical music in schooling without bringing aesthetic ideology along with it. Even though American popular music is increasingly taught, American universities still overwhelmingly focus on Western classical music, and that emphasis still filters down, via university-educator music teachers, into K–12 schooling. To illustrate this, we have included a popular meme that has been circulating for years now in English-speaking, North American music classrooms and on social media. It reflects enduring aesthetic rationales for teaching music in schools. There’s no expectation that music class will lead to lifelong musicking or that music will function as an enjoyable and relaxing pastime. The values of music are thought to be infinitely more profound than everyday considerations:

Social Justice

To me (Vincent), Tom Regelski as a person was and is synonymous with his scholarly work. My interactions with him were limited to either academic discussions about Critical Theory and praxis, or communications pertaining to my volunteer work for the MayDay Group and ACT. Tom approached it all consistently through a patriarchal stance—straight-forward, authoritative, and sometimes vitriolic. As I began my own academic writing, while still teaching K–12 music full time, I resonated nonetheless with Tom’s idea of praxis growing from an ethic of care (Bates 2004) and have found it useful in studying and theorizing anti-rural bias, classism, and ecological sustainability in music education. Still, there seemed to be a disconnect between social justice narratives and Tom’s approach to Critical Theory. I believe this is partially because Tom, following Habermas, skipped over Marx to base his version of Critical Theory on Aristotle:

In the Enlightenment tradition inherited from Kant, and as late as the social theory of Karl Marx and his followers, praxis had been understood in terms of practical work. Jürgen Habermas, a second-generation Critical Theorist, however, returned to Aristotle who had distinguished between three types of knowledge: praxis, theoria, and techne…. Praxis involved ‘doing’ (action) of an ethically prudent kind (because it involves people) rather than ‘making’ (which involves things). Theoria involved what today we would call theoretical knowledge and was to be contemplated for its own sake (although applied theoria could guide techne) and thus was ‘good for’ the life of leisure. Techne, in contrast, involved ‘making’ or ‘producing’ actions (poiesis) and thus the practical knowledge and applied theory needed to bring about certain customary, useful, and reproducible results. (Regelski 2016, 111)

After my doctoral mentor’s untimely death, Tom informally filled that role for me, on an academic level at least, and I will be forever grateful for that. Understanding that my scholarship is my own responsibility, I nevertheless wonder how my academic journey might have been expedited had Tom fully recognized or acknowledged the Marxian roots of Critical Theory. Like the classic story of the poor man who had a dream about a treasure hidden in a faraway place, and then went in search of it only to learn that the treasure was buried under his own hearth at home, I read widely to formulate a basis for a critical class theory of music education only to find that Critical Theory, given its Marxian roots, offered exactly that. In all fairness, as Tom’s theorizing continued to evolve, it appears that he did become more appreciative of Marx. Here’s a footnote from his 2022 article where he advocates for a “praxical” approach to music education, drawing from Ignacio Ellacuría’s discussion of praxis in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Ellacuría follows a Marxian theme of action (praxis) undertaken to foster emancipation from oppressive ideologies. The premise demonstrates how the multiplicity of music praxies has inexorably led to ever-greater possibilities for musicing in society (e.g. cross-over musics, ever new musical technologies)—including as a force for political change. For example, the “Singing Revolution” in Estonia led to freedom from oppressive Soviet rule (Google singingrevolution.com). This Marxian side of praxis theory (viz., Critical Theory) is also central to efforts in music education praxis to overcome poverty, social inequality, racism and other oppressive conditions. Note: Ellacuría’s translator refers to “praxical” bases for effecting change—rather than the adjective “praxial.” The close relationship of “praxical” to “practical” is a useful reminder that, properly understood, praxis is pragmatic in its results. I have therefore newly adopted it hereafter to brand my phenomenological sociology (see Alfred Shultz) of musical praxis from other praxial theory that mainly stress the inevitable differences between musical praxies and the need to account for these differences in education. (Regelski 2022, 46)

Even though Tom didn’t explicitly make this connection until later, the Marxian and social justice bases for praxis were not lost on subsequent theorists such as myself. In a 2016 ACT editorial, for example, I reaffirmed that social justice is the central aim of critical theory, citing Max Horkheimer (1937/1972) among others: “For all its insight into the individual steps in social change and for all the agreement of its elements with the most advanced traditional theories, the critical theory has no specific influence on its side, except concern for the abolition of social injustice” (242, emphasis added). Even though there were and are differences in emphasis and potential incongruities between patriarchy and phronesis, the foundation Tom laid for Critical Theory in music education has been an effective starting point for multiple researchers and theorists, myself included.

Anti-racism

Although as described in the foregoing section, Tom’s later scholarship made the connections between critical theory and concerns for social justice and social change explicit (e.g., Regelski 2016; Regelski and Gates 2009), his writings about culturalism and multiculturalism in a 2002 article, “Critical Education, Culturalism and Multiculturalism,” provided some clues that eventually opened the door to anti-racist approaches to music teaching. Tom, in personal conversations with me (Deb), rarely acknowledged these connections. His discussions in that 2002 article about culturalism and multiculturalism, however, hinted at the critiques of multiculturalism that were growing in other areas of educational discourse (Apple 1993; Ladson-Billings 1996, 1998; McLaren 1997; Sleeter and McLaren 1995; Steinberg 1995), even though the ideas he presented were his own and did not refer to any of the above scholars’ critiques. Despite the increasing importance of anti-racism scholarship in other areas of education, music education was still in a nascent and sometime tentative experiment with multiculturalism, which had begun to gain greater acceptance through the curriculum resource work of scholars like Patricia Sheehan Campbell, but this emerging pedagogical approach did not utilize a critical lens. Music educators generally had not yet paid attention to the critiques of multiculturalism levied by education scholars. Regelski’s philosophical argument in that particular 2002 article, however, opened a space for the critiques that are characteristic of anti-racist scholarship.

One example of the way that Tom’s thinking opened the door for anti-racism scholarship were such statements as: “The idea of multiculturalism presents important challenges to society and thus to schooling. However, despite considerable lip service by opportunists, it is often not taken seriously enough” (Regelski 2002, 2). These words resonated with me as a doctoral student who had recently encountered anti-racist scholarly writing. Not only did I agree with Regelski about multiculturalism not being taken seriously in music education, I felt emboldened to explore the challenges it presented with statements from Regelski like: “if schooling is to contribute to the needs of our society, then music teachers need to take a critical stance on the role and value of music in life and thus of its reasonable place in schooling” (2).

Although an in-depth discussion of Regelski’s 2002 article is beyond the scope of this editorial, in the spirit of reflection on the influence his philosophical work had on music education, it seems appropriate to share a couple of the “aha” moments from this article that guided my early forays into anti-racism music education. In the first major section of the article, Regelski discussed critical theory. Anti-racism education drew quite heavily from the critical thinking of Paolo Freire (Freire 1970, 1998; Freire and Freire 1994), and that of Karl Marx moreso than Habermas, whom Regelski cited. Even so, Habermas’s (1988) thinking on understanding the lifeworlds of others aligned well with anti-racist theories regarding the material impact of racism on students’ well-being. As Regelski explained: “Effective, non-coercive communication and true knowledge … both depend on understanding the lifeworld inhabited by others and the subjective interpretative categories by which they make sense of it” (Regelski 2002, 4). Anti-racist theory relies on the understanding that race is a social construct rather than biologically determined, but even this understanding requires a critical lens. As George Dei explained, “our understandings of race have not shifted far beyond the ills of biological determinism simply through the social theorizing of race” (Dei 2000, 12). In other words, the social construction of race holds the same potential trap to become a subjectively interpreted category that inflicts similar damage to that of biological determinism.

Regelski in this 2002 article discussed how false consciousness results from ideological influences that dominate and control people’s (including educators’) thinking (4). He made clear that ideological influences dominated not only the behavior and culture of North America and Europe, but also music education curricula. European art music represented the lion’s share of curricular repertoire, considered “the best” music and the core of a curriculum that might “make room” for popular music or the music of other cultures (see Reimer 1970, 145, for discussion of the cultural heritage of US citizens)—resulting in what anti-racist scholars label as “token multiculturalism” based on assumptions about the shared cultural heritage of all students in the United States.

In another section of the 2002 article, focused on critical education and music education, Regelski’s argument continued to resonate with anti-racism education principles, where the work of Paolo Freire (1970) loomed large. Regelski, in this section, cited Spring’s description of “critical integrationists,” a forerunner perspective to anti-racism: “For critical integrationists, critical pedagogy is considered a method for educating people to struggle to end all forms of racism. For the critical pluralist, critical pedagogy will prepare people to work to end the sources of discrimination and prejudice in society” (Spring 1991, 148).

While there are many other Regelski statements to which I could refer to illustrate the congruity of his philosophy with anti-racism, I trust that these few examples illustrate for readers how his words supported my interest, as an emerging scholar, to interrogate the surface-level multiculturalism that had become the norm in music teaching. Tom’s praxial philosophy placed strong emphasis on music-making as social action, ethical reflection, and community engagement. He routinely critiqued exclusionary practices rooted in institutional or cultural hierarchies. He encouraged music educators to reflect critically on the ethical, social, and political implications of their work. I took this to heart, particularly because the needs of racialized students in music education were so obviously not being met. His critiques and encouragements, along with those of all the scholars whose work influenced mine, provided a basis to venture into anti-racism—a venture based on the academic tradition of building on the work of others, extending and using it as a springboard into related areas of thought. What I know definitively is that this specific 2002 article, in many respects, provided a philosophical opening to the space for a critical multicultural, anti-racist discourse in music education.

I regret that I never shared with Tom the opening that his scholarship had provided for my own. Perhaps I assumed he knew it because of my long-time association with the MayDay Group, although over the many years of that association, Tom sometimes criticized anti-racism as “niche” scholarship. He once told me that I “saw racism everywhere.” I never argued the point with him, because in truth, I did see racism everywhere and still do. Now, nearly 20 years after publication of my “Can We Talk” article (Bradley 2006), I see even more racism than I did then, as extreme right-wing politics and fascism[2] continue to gain strength across the globe, dismantle DEI initiatives, and make anti-racism and other forms of social justice work increasingly dangerous. When I wrote my first article proposing an anti-racist music education (Bradley 2006), I did not cite the 2002 article of Tom’s, although in hindsight, I certainly could have. At the time, newly appointed to a tenure-track position at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, I was striving to inject a new body of scholarship into the music education discourse. I suppose in some ways I was looking to establish a “niche” for myself in academe. Looking back on the experience of those first reviews of the article and the many questions Tom raised during the editing process, I am surprised that he even agreed to publish the article in ACT. His questions about the content of that article were challenging in ways I had not anticipated; I often felt defensive when I provided the answers, which Tom accepted but always followed with another challenging question. (Readers who knew Tom probably have themselves experienced these types of questions.) His challenges required me to provide better explanations of terminology and information from an unfamiliar discourse (to music educators) for the citations that supported my assertions about whiteness and racism in music education. The result was the 2006 “Can We Talk” article, which over the years has become one of the most frequently cited articles in Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education (Bradley 2006). There is no doubt in my mind that Tom’s rigorous questions as editor of ACT helped to bring that about, and for that, I will always be grateful.

If I could go back in time, I would share with Tom just how his thinking helped open the door to anti-racism music education scholarship. Because I do not know if he and I will have that discussion in the afterlife (would that be heaven or hell?), I trust that my small contribution to this issue of ACT, dedicated to honoring Tom Regelski’s scholarship, will suffice. I hope that readers might take up the questions and criticisms of music education that he raised and let them lead to their own new critical forms of scholarship. It is my homage to a thinker who had great influence on my own work, even if I did not acknowledge it while he lived.

Pragmatist Philosophy and Praxialism

Like his general disposition as a scholar and teacher, Tom Regelski’s praxial philosophy of music education is firmly rooted in the tradition of philosophical pragmatism, which originated in the 19th century writings of C. S. Peirce and was subsequently developed in different ways throughout the twentieth century by William James, John Dewey, George Herbert Mead, and others. The central principle of pragmatism lies in the “pragmatic maxim” coined by Peirce in his 1878 essay, “How to make our ideas clear.” Insisting that “our idea of anything is our idea of its sensible effects” (1934, 5.401), Peirce wrote: “Consider what effects, that might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object” (5.402). The more widely known—but subtly and significantly different—interpretation of that principle, that the core meaning of any concept or proposition could be understood by examining its practical consequences (i.e., what difference it would make in terms of human actions and experiences) was a later adaptation of William James, also advanced by John Dewey, and it is the basis of Tom’s pragmatism as well.

Tom’s pragmatic concern with “what music is ‘good for’” as a music education scholar can be discerned to some degree in his early writings (see Goble 2003, 29-30), but his interest in developing the notions of music as praxis and music education as praxis emerged most clearly after he participated in the first International Symposium on the Philosophy of Music Education at Indiana University (IU) in 1990. David Elliott, Tom, and I (Scott) were seated at the same round table in the IU Musical Arts Center when we heard philosopher Philip Alperson present his paper, “What Should One Expect from a Philosophy of Music Education?,” and the discussion between David and Tom immediately following that presentation foreshadowed changes in each of the two scholars’ thinking. Their subsequent writings provoked an extraordinarily generative dialogue among music educators over the following decades.

In his paper, Alperson (1991) had presented three possible “basic strategies” for understanding and explaining music and music education: First, he described the “formalist aesthetic view,” rooted in the writings of Enlightenment philosophers, according to which music is a fine art, and music education involves training people to perceive and respond appropriately to musical works. Next, he described an “enhanced’ version of aesthetic formalism, which further takes the expressive, representational, and symbolic properties of a musical work into consideration to account for its meaningfulness; the primary purpose of music education in this view is to make insights into these properties accessible to people and thereby to refine their understanding of human feeling. Alperson then proposed a third strategy, a “praxial” one, in which “the attempt is made . . . to understand [music] in terms of the variety of meaning and values evidenced in actual practice in particular cultures” (1991, 228). While compulsory music education in the schools of culturally pluralistic, democratically governed nations had included music of “many lands and peoples” since the inception of music education in Boston in the early 19th century, and music education curricula in the United States were resolutely opened to include “music of all periods, styles, forms, and cultures” (Choate 1968, Section 2) by participants in the Tanglewood Symposium of 1967, Alperson’s argument took the additional step of focusing attention on the motives and intentions of those who undertake different musical practices as well as “the social, historical, and cultural conditions and forces in which practices of music production arise and have meaning” (Alperson 1991, 236).

Stimulated by Alperson’s argument, David Elliott and Tom Regelski both distanced themselves from the philosophies of “music education as aesthetic education” that had been advanced as bases for the practice of school music education by Charles Leonhard and Bennett Reimer two decades earlier. David subsequently developed a highly influential praxial philosophy (1995) built on insights from philosopher of mind Daniel Dennett, philosopher of arts Francis Sparshott, and positive psychology researcher Mihály Csíkszentmihályi, ultimately grounding his philosophy largely in Western psychology. Tom Regelski, in contrast, drew upon Aristotle’s scientific realism, Jurgen Habermas’s communicative rationality, Ellen Dissanayake’s anthropological scholarship, and the pragmatists’ concern with effects to derive his own praxialism, which was arguably somewhat less influential in the short term. However, his argument—following Alperson—that “music—in all its diverse cultural forms—must be understood in terms of its pragmatic consequences for people engaged in the acts of living” (1996, 26) effectively shaped his philosophy to accommodate the different “ways of knowing” and musical practices of culturally different peoples. In making curricular recommendations for what should be taught in schools, Tom accordingly advocated for “general musicianship—the kind of ‘knowing’ and ‘doing’ that travels well” (Regelski 2000, 82), i.e., across different musical traditions, yet he also wrote, “the specific human context and purposes for which music is produced” must always be taken into consideration, since “situatedness … governs the ‘goods’ sought as ‘right results’” (1996, 25). For his carefully constructed pragmatic arguments and for the attention he gave to the practical consequences of musical practices (praxes) in his writings, his work merits consideration as an important contribution to the history of pragmatist philosophy.

Ethnomusicology and Musicology

The relative cultural openness of Tom’s praxial philosophy is manifested in his founding of the MayDay Group (MDG) with J. Terry Gates, a fellow pragmatist in music education (and Dewey scholar). As its members know, the MDG defines itself as an “international think tank of music educators that aims to identify, critique, and change taken-for-granted patterns of professional activity, polemical approaches to method and philosophy, and educational politics and public pressures that threaten effective practice and critical communication in music education” (MDG website). Likely attracted by the MDG’s cultural and conceptual openness, a number of scholars in music education whose research is informed by ethnomusicological methods and perspectives have become centrally involved in the work of the organization, including Danielle Sirek (who studied relationships between cultural identity and musicking in Grenada, West Indies); Brent C. Talbot (who conducted music research in Indonesia and Tanzania), and Anita Prest, myself (Scott), and Héctor Vázquez Córdoba (who conducted research on Indigenous knowledge and musical practices in participation with Coast Salish peoples in British Columbia, Canada). Numerous articles in ACT address topics of ethnomusicological concern, and there is active cross-citation of and by ethnomusicologists in ACT, thus confirming the influence of Tom’s legacy on the field of ethnomusicology. Further, Tom’s writings on praxial music education have influenced scholarship on the teaching of musicology. James Maiello influentially applied Tom’s philosophy both to the development of a praxial philosophy of music history pedagogy (2013) and to the teaching of music history in schools as praxis (2019), and Tom’s approving rejoinder to Maiello’s applications (2013) has been widely cited.

This Issue

Another aspect of Tom Regelski’s academic work that has always seemed incongruous to me (Vincent) was that he shared so little about himself personally or directly in his writing. I have tried to “read into” what he wrote, to catch a glimpse of who he was. In retrospect, I could have made attempts to get to know him on a more personal level all along. Given that critical theorists usually hew to a social constructionist frame of reference, one might still expect that there would be more self-disclosure in his writing. To help fill this gap or oversight, I invited Tom to write a 5,000-word autobiography that was to be included in a future publication. The first article in this issue is the result, lightly edited and with a title and abstract added. The remaining four articles in this issue are summarized below by Deb Bradley who communicated directly with the authors about their manuscripts throughout the process and did most of the editing.

Following from Tom Regelski’s biography, the second article, by Kinh Vu, similarly offers biographical information alongside a unique look at one of Tom Regelski’s earliest published articles, in a 1975 issue of Music Educators’ Journal. The year 1975 represents both the end of the US war in Vietnam and a watershed period in Vu’s personal life journey. Vu’s poignant reflections draw upon what Tom described in 1975 as a “dialectical seesaw”; he brings together the disparate areas of war and music education. This seesaw illustrates “the power of a dialectic that refuses to camp out among certainties pertaining to either music pedagogy or military conflict.” Vu asks readers to consider how “symbolic children” may be caught in the cross-fire of “education-gaming and wargaming alike.”

Christopher Ricketts’s article draws on a 2016 article by Tom Regelski about praxial music education and the writings of Paulo Freire on critical pedagogy to examine the concept of student voice and agency through a critical lens. Ricketts offers what he calls the PRAAX Model—a work in progress model that “positions the teacher not just as a curriculum deliverer, but as a critically engaged practitioner.” An analysis of interviews with five experienced music teachers, offered in the form of vignettes, illustrates the potential for the PRAAX approach to contribute to socially conscious and culturally relevant music learning.

Concluding this issue is the article by Marja Heimonen and Maria Westvall, who write from the Nordic context, “’in dialogue’ with Tom Regelski,” to examine interconnections between the potential roles of music and arts education as a means for co-existence in contemporary society. The authors explore learning and education through the lens of critical pedagogy and counter-critical pedagogy. They describe the current era as one of fear and insecurity; with this understanding, they examine the implications of these conditions for citizenship and artistic citizenship education, and introduce the concept of artizenship as a means of fostering hope for the future.

We (the guest editors—Vince, Deb, and Scott) hope that the diversity and originality of articles in this special issue of ACT can help readers, especially those who may not previously have read much of Tom Regelski’s work, to see the potential range of applications that his theorizing has generated and may continue to generate. He was an original thinker whose philosophical contributions to music education remained, throughout his long career, focused on what is best for students in their music education. This theme is apparent throughout all the authors’ contributions to this special issue of ACT and is a fitting way to honour the work of MayDay Group co-founder and founding editor of Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education.

References

Alperson, Philip. 1991. What should one expect from a philosophy of music education? Journal of Aesthetic Education 25 (3): 215–42.

Apple, Michael. 1993. Constructing the “other”: Rightist reconstructions of common sense. In Race, identity, and representation in education, edited by Cameron McCarthy and Warren Crichlow, 24–39. Routledge.

Bates, Vincent C. 2004. Where should we start? Indications of a nurturant ethic for music education. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 3 (3). http://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Bates3_3.pdf

Bates, Vincent C. 2016. Introduction: Reaffirming commitments to critical theory for social justice. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 15 (5): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.22176/act15.5.1

Bradley, Deborah. 2006. Music education, multiculturalism, and anti-racism—Can we talk? Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 5 (2). http://act.maydaygroup.org/php/previous.php

Bradley, Deborah. 2009. Oh, that magic feeling! Multicultural human subjectivity, community and fascism’s footprints. Philosophy of Music Education Review 17 (1): 56–74. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40327310

Choate, Robert A., ed. 1968. Documentary report of the Tanglewood Symposium: Music in American society. Music Educators National Conference.

Dei, George J. Sefa. 2000. Power, knowledge, and anti-racism education. Edited by George Sefa Dei and Agnes Calliste. Fernwood Publishing.

Elliott, David. 1995. Music matters: A new philosophy of music education. Oxford.

Freire, Paulo. 1970. Pedagogy of the oppressed. Seabury Press.

Freire, Paulo. 1998. Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Critical perspectives series. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Freire, Paulo, and Ana Maria Araâujo Freire. 1994. Pedagogy of hope: Reliving pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

Goble, J. Scott. 2003. Perspectives on practice: A pragmatic comparison of the praxial philosophies of David Elliott and Thomas Regelski. Philosophy of Music Education Review 11 (1): 23–44. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/philosophy_of_music_education_review/v011/11.1goble.html

Habermas, Jürgen. 1988. On the logic of the social sciences. Studies in contemporary German social thought. MIT Press.

Horkheimer, Max. 1937/1972. Traditional and critical theory. Translated by Matthew J. O’Connell. In Critical Theory: Selected essays. Herder & Herder. https://monoskop.org/images/7/74/Horkheimer_Max_Critical_Theory_Selected_Essays_2002.pdf

Kertz-Welzel, Alexandria. 2005. The pied piper of Hamelin: Adorno on music education. Research Studies in Music Education 25 (1): 1–12. https://www.researchgate.net/publiction/258183379_The_Pied_Piper_of_Hamelin_Adorno_on_Music_Education#fullTextFileContent

Ladson-Billings, Gloria. 1996. “Your blues ain’t like mine”: Keeping issues of race and racism on the multicultural agenda. Theory into Practice 35 (4): 248–55.

Ladson-Billings, Gloria. 1998. Just what is critical race theory and what’s it doing in a nice field like education? Qualitative Studies in Education 11 (1): 7–24.

Maiello, James V. 2013. Towards a praxial philosophy of music history pedagogy. Journal of Music History Pedagogy 4 (1): 71–108.

Maiello, James V. 2019. A praxial approach to musicology in the secondary school curriculum. Musica Docta 9: 57–65.

Mantie, Roger. 2016. Answers without questions. Review of A Brief Introduction to a Philosophy of Music and Music Education by Thomas A. Regelski. Philosophy of Music Education Review 24 (2): 213–19.

McLaren, Peter. 1997. Unthinking whiteness, rethinking democracy: or farewell to the blonde beast; towards a revolutionary multiculturalism. Educational foundations 11 (2): 5–39.

Peirce, Charles Sanders. 1931–35. Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Vols. I–VI. Edited by Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss. Harvard University Press.

Regelski, Thomas A. 1996. Prolegomenon to a praxial philosophy of music and music education. Finnish Journal of Music Education 1 (1): 23–39.

Regelski, Thomas A. 2000. Accounting for all praxis: An essay critique of David Elliott’s Music Matters. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 144: 61–88.

Regelski, Thomas A. 2002. “Critical education,” culturalism and multiculturalism. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 1 (1): 2–40. https://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Regelski1_1.pdf

Regelski, Thomas A. 2006. “Music appreciation” as praxis. Music Education Research 8 (2): 281–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613800600779584

Regelski, Thomas A. 2007. Amateuring in music and its rivals. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 6 (3). http://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Regelski6_3.pdf

Regelski, Thomas A. 2009. The ethics of music teaching as profession and praxis. Visions of Research in Music Education 13. http://www-usr.rider.edu/~vrme/

Regelski, Thomas A. 2011. Praxialism and “aesthetic this, aesthetic that, aesthetic whatever.” Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 10 (2): 61–99. http://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Regelski10_2.pdf

Regelski, Thomas A. 2013. Music and the teaching of music history as praxis: A reply to James Maiello. Journal of Music History Pedagogy 4 (1): 109–36.

Regelski, Thomas A. 2016. Music, music education, and institutional ideology: A praxial philosophy of music sociality. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 15 (2): 10–45. act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Regelski15_2.pdf

Regelski, Thomas A. 2017. Pragmatism, praxis, and naturalism: The importance for music education on intentionality and consummatory experience in musical praxes. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 16 (2): 102–43. https://doi.org/10.22176/act16.2.102

Regelski, Thomas A. 2020. Tractate on critical theory and praxis: Implications for professionalizing music education. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 19 (1): 6–53. https://doi.org/ 10.22176/act19.1.6

Regelski, Thomas A. 2022. Musical value and praxical music education. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 21 (1): 15–55. https://doi.org/10.22176/act21.1.15

Regelski, Thomas A., and J. Terry Gates, eds. 2009. Music education for changing times: Guiding visions for practice. Springer.

Reimer, Bennett. 1970. A philosophy of music education. Prentice-Hall.

Sleeter, Christine E., and Peter McLaren, eds. 1995. Multicultural education, critical pedagogy, and the politics of difference. State University of New York Press.

Spring, Joel. 1991. American education: An introduction to social and political aspects. 5th ed. Longman.

Steinberg, Shirley R. 1995. Critical multiculturalism and democratic schooling: An interview with Peter L. McLaren and Joe Kincheloe. In Multicultural education, critical pedagogy, and the politics of difference, edited by Christine E. Sleeter and Peter L. McLaren, 392–405. State University of New York Press.

Westerlund, Heidi. 2003. Reconsidering aesthetic experience in praxial music education. Philosophy of Music Education Review 11 (1): 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1353/pme.2003.0008

[1] Alexandra Kertz-Weltzel (2005) helpfully illuminated related concerns raised by Theodor Adorno in Germany both before and after World War II on the misuse of music education for ideological purposes.

[2] For an anti-racist look at some early warning signs of fascism in music education in the US, see Bradley 2009.