FRANCIS WARD

Dublin City University (Ireland)

November 2023

Published in Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 22 (4): 87–130. [pdf] https://doi.org/10.22176/act22.4.87

Abstract: This study utilises virtual ethnography to examine “Mary O’s Virtual Session,” a weekly Irish traditional music session that, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, migrated online using YouTube Live—a platform key to the study for facilitating interactive, synchronous learning. Drawing on theoretical frameworks by scholars including Turino (2008) and Jenkins (2006), this research interrogates “participation” and examines the transformative potential of this virtual session as a locus for music transmission, challenging traditional practices’ reliance on co-location. Despite limitations imposed by the virtual environment, the research posits that this adaptation cultivated a crucial “nexus of learning,” facilitating substantial pedagogical, musical, and social continuities for music learners amidst the pandemic. The findings provide valuable insights for music educators in the digital age, suggesting the importance of media convergence in developing supports to enable learner participation in virtual spaces. This study underscores the ongoing evolution and specialisation of online teaching in music education.

Keywords: Music education, participatory, Irish traditional music, online teaching, online learning, transmission, YouTube

Introduction—Irish Traditional Music Transmission and the Internet

The Internet and advent of Web 2.0 in particular have transformed the landscape of Irish traditional music (ITM), revolutionising its transmission and the ways in which musicians share music, connect, and collaborate. A diverse range of platforms provide virtual spaces for performance and sharing, including video streaming services such as YouTube and Vimeo; audio streaming services such as Spotify, Amazon Music, and Apple Music; online radio stations and digital archives such as the Irish Traditional Music Archive (ITMA.ie); user-generated content (UGC) on blogs and forums; and tune archives such as those hosted on TheSession.org. A wealth of specialist teaching websites, such as the Online Academy of Irish Music (OAIM.ie), have also evolved, and teachers of ITM are making increasing use of applications such as Zoom to facilitate synchronous remote instruction. This paper examines how the particular platform of YouTube Live was used during the COVID-19 pandemic to livestream a weekly ITM “virtual session.” The analysis reveals that the virtual session ultimately created a critical nexus of learning, providing and enabling significant pedagogical, musical, and social continuities for ITM learners despite the challenges and limitations of the virtual space.

Defining the ITM Session

ITM is a highly participatory musical culture, exemplified through one of its central communal music making activities, the seisiún (henceforth “session”—see Cawley 2020; Foy and Adams 2009). The session is an example of a synchronic[1] music tradition (Cayari 2018), in which the focus of the musical practice is primarily on live, simultaneous performances, with an emphasis on the shared experience between those present, in contrast to recorded or mediated experiences. It embodies the fundamental qualities of a “participatory culture” (Jenkins 2006), namely inclusivity, collaboration, and active participation, and is an example of “participatory music making” (Turino 2008), characterised by communal participation and a shared musical experience. A cornerstone of Irish culture, the session features in all diasporic sites of Irish culture and indeed beyond, typically taking place in public houses,[2] where the shared informal musical practice connects performers, students, and listeners of ITM.

ITM sessions can be spontaneous, or more formally organised events that occur at a fixed time in a fixed venue, usually on a weekly basis in the evening. One such example of an organised session is the weekly session on Thursday night at Mary O’s Irish Pub in Manhattan, led by fiddle teacher and player Caitlin Warbelow. The leader of an organised session is responsible for attending the session each week, starting the music making at a certain time, maintaining a steady stream of music performance for the duration of the session, and often has the option of inviting guest musicians to co-lead the session. The session leader and invited guests are normally compensated for their time and are responsible for choosing repertoire and encouraging other musicians who have attended to participate. There is a loose performers-audience presentation, though the boundaries are fluid, with attendees free to shift in their role from active listener to performer, singing a song, dancing, or indeed joining in the instrumental performance at some stage during the night. Others present may simply listen and chat informally while the session goes on. The session is not usually amplified, and the performance is informal; attendees chat between playing, connecting with friends, and meeting new people in a relaxed atmosphere, often with some drinks.

Leaders of a session usually vary the repertoire played in any one night—drawing on potentially thousands of tunes in their ITM repertoire—and normally play them at a fast tempo. However, Mary O’s Thursday night session, known as a “slow session,” is specifically designed for novice students of ITM, with only the most common tunes[3] selected for performance, played at slower tempi to maximise the chances of participation for attendees.[4] While Caitlin, leader of Mary O’s slow session, is a professional musician, as are the various invited guest musicians who join her each week, the rest of the 30 or so musicians who attend weekly are amateur adult students of ITM, many of whom are taught by Caitlin in her classes around the city. In many ways, this session serves as an outlet where students get to “try out” what they have been learning in classes, where they can hear more skilful performers—learning through observation, imitation, and often recording the music for later reference—and where they can socialise with each other.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, restrictions on social and musical gatherings prompted Caitlin to move this weekly session online, livestreaming it as “Mary O’s Virtual Session” via YouTube Live.[5] As it grew in popularity and global reach, the series was retitled “Tune Supply’s Common Tunes at Reasonable Speeds.” A total of 81 virtual sessions have been broadcasted, beginning in March 2020 through to February 2022, with each session lasting between 1.5 and 2.5 hours.

Research Aims and Significance

Ultimately, this study aims to contribute to emerging scholarship in music education on virtual contexts for teaching and learning, and the specialisation of online teaching, through a case study of Mary O’s Virtual Session. More specifically, it aims to focus attention on the concept of learner participation, and consequently, how the unique and innovative learning pathways that emerge from Mary O’s Virtual Session foster musical, pedagogical, and social continuities for learners.

Mary O’s virtual ITM session represents a significant and unique form of musical engagement, aiming to recreate the synchronic through the mediated. While other websites that specifically focus on ITM learning, such as the Online Academy of Irish Music, continued to offer pre-recorded suites of lessons and livestreaming of music performances during the pandemic, the series of Mary O’s Virtual Sessions created by Tune Supply emerged as a consistent offering which uniquely aimed to mimic the interactive and live dynamic of the ITM session. This represents a transformative adaptation of the traditional setting.

Analysis of the learning nexus that emerged around the virtual sessions demonstrates the online space’s capacity to facilitate music transmission. This is particularly noteworthy considering the traditional session’s reliance on physical co-location. Within this context, the analysis of the virtual session which follows is more specifically informed by theoretical concepts and frameworks pertaining to “participation” as developed by prominent musicologist Thomas Turino (2008) and leading new media studies scholar Henry Jenkins (2006, 2009), and as applied to music education by scholars Janice Waldron (2013b, 2016) and Evan Tobias (2013, 2020).[6] This scholarship, which explores how one might experience and/or understand “participation,” highlights the virtual session’s transformative potential as an essential locus for the online transmission of music during the pandemic. This transition was made possible through leveraging the innovative opportunities for participation that virtual environments afford. These virtual settings fostered the creation of a structured environment that facilitated musical expression, pedagogical interaction, and social connectivity.

The literature review situates the study within scholarship that encompasses vernacular music, online teaching and learning, and informal learning via YouTube; and briefly reviews the application of Jenkins’ concept of participatory culture to online music learning. Subsequently, the analysis goes on to introduce and delineate the workings of Mary O’s Virtual Session. Finally, in the discussion, detailed consideration is given to what characterises learner participation by employing established frameworks by Turino and Jenkins; and recognising the diversity of roles and multifaceted identities emerging through participation. This approach provides insights into the ways in which participation nurtured musical, pedagogical, and social continuities for learners of ITM during the pandemic; and seeks to highlight the distinctive features that potentially elevated the success of the Tune Supply virtual sessions, surpassing prior attempts to transpose the session experience into the online environment.

Research Context/Literature Vernacular Music and Online Learning

This work is set against the backdrop of a growing body of research within music education and ethnomusicology on learning ITM (and folk music more broadly) and the Internet (e.g., Bayley and Waldron 2020; Kenny 2013, 2014, 2016; Kruse and Veblen 2013; Waldron 2011a, 2011b, 2013a, 2013b, 2016; Ward 2019). Kruse and Veblen (2013) have examined a number of YouTube instructional videos across various genres of traditional and folk music, illustrating the value of these videos for analysing music pedagogy, and concluding that YouTube is a major catalyst not just for musical and educational change, but for social change. Waldron’s work has made a significant contribution to understanding music learning in the online space, introducing the terms “informal music learning practices 2.0” (Waldron 2016, 93; after Green 2002), and “pedagogical syncretism” (2013b, 266).

The former term allows for the conceptualisation of informal music learning to go beyond simply learning outside the classroom, to specifically include how learners independently use the Internet to develop their musical skills (Waldron 2013b; see also Lange 2018). The ubiquity of the Internet makes it difficult to imagine any self-directed learner of music in the present day who does not draw upon it as a vital learning tool; and a “pedagogical syncretism” describes the ways in which these learners construct their unique approach to music learning, combining a range of learning modes (Waldron 2013b, 266). These modes include aural/oral, visual (through a wide range of notation systems including standard staff notation, ABC notation, and tabs) and observational (drawing heavily on YouTube videos and embedded videos in specialist music learning websites) (Waldron 2013b). Importantly, this approach fosters learner agency, allowing students to take responsibility for, make specific choices about, and plan the trajectory of their musical development.

The Online Academy of Irish Music (OAIM) is one of the most developed and well-researched specialist online teaching platforms for Irish traditional music (Bayley and Waldron 2020; Kenny 2013, 2014, 2016; Waldron 2011a, 2013a, 2013b, 2016; Ward 2016, 2019). At the launch of their website in 2010, the OAIM broadcasted a live “virtual session” from a pub setting in Co. Clare, Ireland. However, the interaction during this one-off event was limited, primarily serving the purpose of raising awareness about the website and attracting new subscribers, rather than facilitating virtual participation or online learning, and the practice did not continue.

Bayley and Waldron (2020) explore the perspective of OAIM students by engaging with adult learners about their experiences with both the OAIM online lessons and the OAIM face-to-face summer school. They characterise the OAIM’s combined online and offline programs as a “convergent community,” following Jenkins (2006), signifying a community that exists in both online and offline settings. Their findings revealed that adult learners presented differing views on what pedagogical approaches proved effective for them within these two contexts.

Furthermore, the development of “virtual pedagogies” (Ward 2019, 11) for use in specialist music learning websites, such as the OAIM, demonstrates how the Internet also affords agency to teachers. These are carefully crafted approaches to music education developed by those whose expertise lies in online music teaching and learning. For example, the OAIM.ie website offers “3D virtual sessions”—a virtual reality experience in which users, who are wearing VR headsets, are immersed in a 360 degrees video of sessions pre-recorded in Co. Clare in Ireland. Through these virtual session videos, students of ITM can observe the entire session environment from the perspective of the centre of the session, including observing musical and social interactions (see Ward 2019), session etiquette, and audience interaction and participation, and hear the music and perform along with the session from the environs of their own homes.

These advancements in music education highlight a growing ambiguity between formal and informal learning. Drawing on music educator Folkestad’s distinction, formal learning is typified by its structured nature and teacher-led approach, while informal learning is more autonomous, drawing on peer interactions and self-guided exploration (2006). This blending of approaches along the learning spectrum has led to the emergence of a new professional niche in music education, focusing on the fusion of formal and informal pedagogical techniques in the virtual space.

YouTube and Music Education

This study is also informed by research that considers music education and YouTube beyond the focus of vernacular music. Cayari (2011) explored the “YouTube Effect,” considering how YouTube has influenced the consumption, creation, and sharing of music, through the case study of a teenage popular musician. He reminds us that “the users of technology shape the technology’s purpose as the technology shapes the users’ culture” (Cayari 2011, 6). Thus, music education practices, including those in the informal realm of learning as well as classroom practice, are informed and transformed by developments in technology and how educators conceive of their use.

At the time of writing in 2011, Cayari cautioned that YouTube was a relatively new technology, with the value of its long-term use not proven; it is now clear that YouTube has become a staple platform for recreational and educational use. Like any long-lasting technology, it has continued to develop and respond to the needs of its users and to make use of evolving infrastructures, including the development of livestreaming via YouTube Live, which launched in 2011. Cayari’s conclusions highlight that musicians employ YouTube for more than just sharing music videos; it is also used as a social networking site that encourages participation through social interaction (2011). This is evident in the case study of a particular musician he presents, in how relationships are established and developed with fellow musicians, and with the broader listening audience.

YouTube and Informal Learning

The idea that learning via YouTube is socially oriented extends beyond music education, as explored in Lange’s (2018) work on informal learning on YouTube more generally. Through her exploration of tutorial videos, which are mainly focussed on video production skills, she illustrates that self-initiated, self-paced learning is a phenomenon not exclusive to music learning, and states that informal learning on YouTube can take place in a number of ways. Firstly, viewers can learn from the content of videos, and through interactions with others, for example, through exchanges in the comments section. Secondly, video creators themselves can learn from critical feedback posted to their videos, which can inform the self-assessment of their own work. This informal learning can be considered participatory in how it creates peer-to-peer connections, with learning entwined with the process of socialisation. Lange concluded that “more organic interactive learning is occurring in everyday digital environments of sociality and play between people in similar age cohorts or within multigenerational spaces of shared interests” (2018, 2).

Usefully, Lange (2018) defines three types of tutorials. The first is referred to as the more “traditional type of tutorial,” which focuses on teaching a specific skill. The second she terms a “walk through,” which in the music context, might be translated as a performance, or demonstration of a task. The third type is known as a “guide,” which focuses on providing information in general terms. The virtual ITM session, and the associated learning processes which will be discussed in due course, in fact combine all three types of tutorial presented by Lange, and indeed go beyond the confines of these in creating a unique online format which facilitates online learning and maximises participation.

Online Music Learning and Participatory Culture

Student virtual ensemble performances from YouTube are the focus of Cayari’s later work, asserting that student participation develops knowledge and skills which can foster “lifelong creative music [making]” (2018, 373). In doing so, he connects participatory culture practices with synchronic musical traditions, framing the virtual ensemble as one of the many avenues through which meaningful musical experiences can be achieved. He asks three questions pertinent to this study: How can synchronic performance ensemble participants expand their approaches beyond physical rehearsal rooms to mediated spaces? In what ways can the traditions of performance-based ensembles be connected to the practices of recording and digital artists? How might the practices that are part of synchronic ensembles offer support to mediated creation? (Cayari 2018, 361).

Scholars such as Waldron (2016), Waldron, Mantie, Partti, and Tobias (2018), and Tobias (2013, 2020) make further connections with the new media concept of participatory culture (Jenkins 2009) and indeed with the musicological concept of participatory music making (Turino 2008). Waldron’s (2016) case study of the Online Academy of Irish Music’s summer school focused on music students who combined learning online with physical attendance at a week of music classes in Ireland. Her paper frames ITM learning as both participatory, drawing on Turino’s conceptualisation of fields of artistic practice; and as participatory culture, based on Jenkins’s concept in new media education. From her fieldwork with music students of ITM, she concludes that their ultimate goal was to be able to participate in sessions. This is similar to findings of my own previous research, which found that learner engagement in an online participatory culture—the Online Academy of Irish Music—enabled involvement in the face-to-face participatory music making of the ITM session (see Ward 2019).

In their exploration of both informal and formal music learning contexts, Waldron, Mantie, Partti, and Tobias (2018) consider a variety of musical practices as participatory culture. Their work highlights and challenges the understandings and applications of the ideals of participatory culture within these contexts. They outline the potential for thinking of music learning as participatory culture to foster creative music making; and highlight connections between music learning in the classroom and musical encounters outside the classroom, recognising that classroom musical learning is often only one node in a larger network of experience which can foster musical development. In their consideration of music making across online, offline, and convergent contexts, they ask critical questions of each, including what participatory culture looks like; who can and who can’t participate; and how these ideas might challenge us to reconsider common practices in music teaching and learning (Waldron et al. 2018). The very purpose of the current study is to present an instance of what participatory culture can look like in the context of music learning, and to think critically about access and transformation of pedagogical practice.

Tobias (2013), in his study into how music educators can align school music programmes with how people engage with music in contemporary society, delves further into Jenkins’ works, moving towards the development of a pedagogy of participatory culture. A pedagogy of participatory culture in this case is characterised by the careful integration of “media convergence” Jenkins (2006, 282), wherein older forms of media (such as television, radio, books, and movies), are experienced and understood through newer forms of media (websites, social media, mobile apps, software) (Jenkins 2006; see also Tobias 2013). In his more recent work, Tobias introduces the term “sonic participatory cultures” to bridge the discourse on participatory cultures within new media studies with a more field-specific understanding of digitally mediated musical engagement (2020). His study situates social media within the context of sonic participatory cultures and identifies potential for music learning and teaching in this context, investigating how this potential can be leveraged and realised within music programmes for young people (Tobias 2020).

The studies above frame the context for understanding how an ITM session—a vernacular music practice, normally rooted in a specific locale—has transitioned and been reshaped within the digital media landscape, and yet retains a strong focus on musical growth and social engagement. While informed by the concept of participation from both musicology and new media studies, the current study aims to build on this scholarship to develop domain specific knowledge and understanding on how contemporary practices in participatory music education can inform approaches to teaching and learning across diverse music learning contexts.

Method

This case study on the virtual session forms part of a broader ongoing ethnography of ITM learning and the Internet (Ward 2016, 2019). Ethnography is a methodological approach which aims to describe, analyse, and understand a particular culture (Krueger 2020; Popkewitz 1981), with the aim of observing social interaction in a natural setting (Krueger 2020). These natural settings in recent years have expanded to include the online spaces created through digitally mediated music making, teaching, and learning.

While the author’s ongoing broader ethnography uses a blended approach, employing both standard and virtual ethnographic methods, this particular case study employs online ethnography (Hine 2000, 2005, 2015; Kozinets 2010; Lysloff 2003; Veblen and Kruse 2019), and seeks to understand music participation, teaching, and learning in the particular case of Mary O’s Virtual Session. The unique challenge of the global pandemic, in which both in-person music making, and in-person research activity were severely hampered, makes this methodological approach seem particularly suitable, in considering how technologies, such as the Internet, are both adopted and adapted (Hine 2015) in the context of music making. Indeed, global pandemic aside, when music educators are no longer restricted to working in the sole medium of face-to-face interaction, it makes sense to embrace the exploration of other media (such as the Internet) which facilitate music teaching and learning, to realise the full breadth of contemporary music education practice.

However, in order to contextualise and understand music making in the online context, I echo Hine’s assertion that this is not ethnography through the Internet, “because in order to understand mediated communications one is also often led to study face-to-face settings in which they are produced and consumed, and to comprehend the settings in which they become embedded” (Hine 2015, 5–6). Hence, my knowledge and experience as a music educator and Irish traditional musician, and the contextualisation of this case study within a broader ethnography of ITM transmission, inform my interpretation, analysis, and conclusions about this particular context.

The fieldwork site for this case study is the musical and social online space created through the weekly Mary O’s Virtual Sessions and the accompanying Virtual Learning Series. A standard ethnographic repertoire of methods was employed, including participant-observation (or learning/researching-by-doing) in the YouTube Live broadcasts. This synchronous interaction, by performing along with the livestream from home, participating in the chat with other viewers, and responding to musical and social cues, allowed me to take on the role of virtual session participant. Observation also took place, post-broadcast, through the analysis of a selection of the virtual sessions which had been archived as standard YouTube videos (n=20) and of videos in the Virtual Learning Series (n=8). Contents of the chat box and standard video comments for these videos were also examined, and various artefacts were analysed such as tune lists, sound files, and other hyperlinked resources to Internet sites (e.g., TheSession.org). Additionally, semi-structured interviews were conducted with key informants, including two interviews with Caitlin Warbelow—musician, teacher, and co-creator and co-host of Tune Supply, the company who created the virtual sessions. The first interview took place during the pandemic, in the height of the production of the virtual sessions, and the second interview took place post-pandemic. Interviews were also conducted post-pandemic with five adult music learners who engaged with the virtual sessions and who ranged from novice to advanced in terms of self-reported skill level. Finally, multiple e-mail exchanges with these informants, including follow-up emails with questions post-interview, complete the data set.[7]

Analysis

The collected data was weaved together to create a coherent picture of how the virtual session worked. Inductive coding (Creswell 2012, 243) and thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006) resulted in the development of a number of themes. The first theme includes descriptive and coherent narratives of how the session functioned, its initial aims, audience, and details of how the live broadcast was produced, and of pre- and post-production activities. The second theme focuses on participation and illustrates how the virtual session facilitated musical and social participation. The third theme highlights the complex range of roles and identities participants inhabit while taking part in the virtual session, and how their positioning affects the manner in which their participation is conceptualised.

Mary O’s Virtual Session

Mary O’s Virtual Session was created by Caitlin Warbelow and Chris Ranney. Caitlin plays fiddle and teaches at multiple locations across New York City. Chris plays piano and was responsible for the sleek—and increasingly sophisticated—content production of the virtual sessions. Caitlin and Chris co-hosted the virtual sessions, which had two main aims. Firstly, it aimed to maintain the musical practice of, and social connection between, Caitlin’s students who wished to continue learning and communally performing ITM during the pandemic. Secondly, it aimed to generate income for Irish traditional musicians during the pandemic, when revenue-generating regular gigs and music classes were widely cancelled.[8] The virtual session featured different guest musicians each week, and the regular hosts and various guest musicians were compensated through a “pay-what-you-can” system linked to the YouTube Live livestream.

The initial audience for the virtual sessions was Caitlin’s fiddle students and other musicians who attended the Mary O’s face-to-face session, physically based in the environs of Manhattan. Caitlin shares the initial rationale for creating Mary O’s slow session and later, the virtual sessions:

Caitlin: I started a session about five years ago called Mary O’s and the reason I started it was because I do a lot of teaching. I noticed that there was no kind of stepping stone session in New York for people to go from, “ok, I want to play Irish music too” … but the jump from here [beginner] to here [competent to play in a session] is impossible, basically. So, I thought, you know, I’m going to start like a true slow session for my students who need that stepping stone. And so that community had been going for five years by the time the pandemic hit, and it is a very close knit, inclusive, caring group of people. They all check in on each other. They practised with each other outside of the session. They celebrate each other’s birthdays, like it’s more than just playing music together. It’s a community. So, when the session went online, it was easy for us to bring that whole community to the YouTube stream. And the thing about YouTube is there’s a chat window. I did not think this was going to work, but for whatever reason, it does approximate the kind of the session atmosphere, because everybody’s in there talking to each other in the chat while we’re playing the tunes or between the tunes, and it does give that feeling like you’re sitting there with everybody else in the bar somehow.

While initially the virtual session attracted the “regular” Mary O’s crowd, it soon became popular internationally, attracting hundreds of viewers on any given night. Audience expansion was through word of mouth, social media coverage, and through the inclusion of a diverse selection of international Irish traditional and Celtic guest musicians, each of whom brought their own “local” audiences which developed the cumulative whole. Fieldwork highlighted that the virtual sessions were highly valued by those musicians who were living in small or rural areas, and/or areas without regular access to ITM sessions. This demand persisted beyond the conclusion of the pandemic, signifying their utility beyond a means to cope with the lockdowns. The virtual sessions gave them access to high quality ITM performances which they could play along with, learn from, and/or listen to. Analysis of YouTube statistics indicates that viewers came from countries well beyond the USA East Coast and time zones (i.e., New York, where Mary O’s is situated), including throughout North America, South America, Europe, Asia, and Australia.

How does the virtual session work?

The Live Broadcast

The live broadcast of the virtual session opens with a title sequence, followed by an introduction from the hosts. They then introduce the structure of the session, naming the guest musicians and informing the viewers of how they can contribute payment for the virtual sessions, and often do a review of any general correspondence received from previous weeks.[9] Viewers respond in the chat box to what’s happening on screen, to which the hosts sometimes respond orally. The hosts also “catch up” and contribute to the live chat during the broadcast of the pre-recorded guest musicians’ performances, when they have a break from presenting and performing live.

The first set of tunes is then introduced, named, and Caitlin and her co-host Chris play the tunes live, on the assumption that some viewers are playing along, and some are listening, as in a regular ITM session. The names of the tunes and their keys are displayed in a banner at the bottom of the screen. The following transcript extract from one of the virtual sessions demonstrates how Caitlin introduces the first set of tunes: attempts to connect with her students and broader audience are evident, in her requests for viewers to play along and/or provide an alternative tune title:

These are some tunes that we always play at Mary O’s, so hopefully the regulars will know these, and the second tune is one that my Irish Arts Center level two students just learned this week so hopefully they can play along. The first one’s called the Legacy Jig… The second tune probably has a name besides what I know it as, maybe somebody can put it in the comments, I know it as Eddie Kelly’s number two, and the third one is of course the Cliffs of Moher because we are going to be transported to County Clare as we play this set. (Tune Supply 2020, 0:04:00)

Connections are also made with the “theme of the week”; in this case, the theme is the “County Clare Edition” (County Clare is a hotbed for Irish music culture), connecting to the tune called the “Cliffs of Moher,” named after the dramatic sea cliffs in this area located on the west coast of Ireland. Viewers can also participate in non-performative ways, for example, by responding in the chat box to the music during and after the set has finished. Responses might include, for example, praise for tune choices, alternative names for tunes, recommendations of particular recordings of a tune for other viewers, and requests to play more slowly (so that amateur musicians at home can play along with more success). Informal chatter and banter are also commonplace. More structured dialogue develops throughout the duration of the virtual session livestream and draws on a regular list of topics detailed later. Generally, after two live sets performed by the hosts, the virtual session moves on to feature the guest musicians’ contributions.

The virtual session was created to mimic Mary O’s Thursday night “slow” session. In keeping with the pedagogical purpose of the slow session, the hosts perform commonly known tunes only, at a slow tempo, to maximise the number of musicians who can play along. However, it sometimes proves challenging to persuade guest musicians to agree to the same, as Caitlin shares:

Caitlin: All of the guests are professional Irish musicians, and some of them are quite high-level professionals who would not usually play or want to play at a slow speed or common tunes. They want to show off their best stuff, especially if it’s going online. So, I had a lot of trouble getting them to play common stuff slowly and sometimes I’m not successful in that. So, they might just blast away on some tunes which people like. But then we get complaints from people saying, like, why would I be paying money if it’s not tunes that I can play along with? Like, that’s the reason that I come to the session, because I want to play along. So, we’ve got to walk a very tight rope sort of line in order to keep people happy, but also keep the guests [musicians] happy. So anyways, we always start with a really slow tune to keep people happy.

This illustrates a tension between Caitlin’s understanding of the virtual session as primarily pedagogical in its orientation, and guest musicians’ eagerness to use it as a performance platform. Despite this tension, the virtual session series successfully attracted hundreds of guest musicians, who submitted their performances as pre-recorded videos in the days before the broadcast on which they were due to appear. These videos were then incorporated seamlessly into the livestream. Viewers can play along with these tunes, and/or respond in the chat. In some cases, guest musicians have tuned in for the livestream of the virtual session and interact with the other viewers through the chat box while their pre-recorded performance video is being broadcast. Like the hosts, they engage in chatter about the music and in general banter.

Figure 1. The YouTube Live interface. Note the main video area and the live chat box which facilitates synchronous interaction for viewers.

Figure 1. The YouTube Live interface. Note the main video area and the live chat box which facilitates synchronous interaction for viewers.

Pre-Broadcast—Preparing to Participate

In the majority of the virtual sessions, the performance playlist is preselected from commonly known tunes, and each week’s unique playlist is added to a master shared document called the “Cliff Notes.” This is in keeping with the nature of the “slow session,” which is aimed at ITM amateur players. The document includes the names of all tunes that will be played in the virtual session on a particular night, with hyperlinks to the notation and recordings of tunes on the website TheSession.org, a common ITM online database of tunes. Thus, musicians can prepare to participate by learning or practising these tunes before the live broadcast of the virtual session, guaranteeing participation. This is in contrast to the face-to-face session, where set lists are not shared ahead of time, and where musicians are encouraged to learn unfamiliar tunes “by ear” in the moment. Caitlin debated the merits of the setlist, finally settling on the needs of the learners:

Caitlin: I did not want to do that [create the playlists] ahead of time because to me, like a session doesn’t have a playlist. We all get together and play whatever’s in our heads. The problem was that people who were watching the session like, they’re mostly adult amateurs. And their goal is to be learning… I had to realise that my goal at the session is not the same as these people’s goals and they want to prepare. We started releasing the tunes that were going to be played ahead of time to the mailing list, and we also try to update what we call the Cliff Notes document. We linked to The Session.org [where tune notation is available], which I also don’t like doing because I just feel very strongly that this music should be learned by ear. But I guess, like the older I’ve gotten, the more I have realised, the more the more adults I’ve taught, the more I realise that my pure views about what should happen are not that important. The important thing is that people are playing, that they have the resources that they want in order to play. And it’s my job to guide them, but not to stop them from doing something because I don’t think it’s the pure correct way to do things. You know what I mean?

Guest musicians who contribute to the virtual session may also create YouTube tutorial videos in which they “pre-teach” the tunes they will perform during their guest slot on the virtual session, and these videos were uploaded 1–2 weeks before the scheduled broadcast. Musicians therefore have the opportunity to learn these tunes from the guest performers, aurally and visually from tutorial videos and any other recordings they source, and from various forms of notation, thus enabling their future participation at the virtual session. Viewers of the virtual session can also participate by sending in a video of themselves playing.

The creation of a number of virtual ensemble style videos was additionally facilitated by Tune Supply, with practice tracks sent out with which learners could record themselves, further encouraging performance as participation.[10] These videos were incorporated into the livestream as a pre-recorded segment, as with guest musician video contributions.

Post-Broadcast—Archive of Virtual Sessions as a Learning Resource

Post-broadcast, the YouTube livestream was archived as a regular YouTube video. After the first few virtual sessions, viewers began enhancing the usability of the videos by adding time indexes in the comments section. They indexed the various sets of tunes with timestamps, allowing others to navigate directly to specific parts of the video to listen and/or learn particular tunes of interest. Responding to this input from viewers, the virtual session hosts added timestamps to many of the future videos, indicating where various sets of tunes begin, to allow the use of the videos as an archive resource. The YouTube links and timestamps were added to the “Cliff Notes” document mentioned earlier.

Thus, over time, while the synchronous live virtual session presents opportunities to learn, a rich archive of multimedia material was also developed for asynchronous consumption. Since the conclusion of the virtual sessions’ broadcast, a musician with a background in web coding has indexed this archive. This archive is now presented on a web page containing a list of tune names. When a tune name is selected, the user is shown a list of YouTube URLs, each with time indexes indicating where that specific tune was performed in the virtual session series.[11] Tune names act as a link between learning aurally from the video resources and learning from the written notation of tunes. This index, therefore, represents a valuable example of some of the user-generated content (UGC) which supports learning around the virtual sessions.

Virtual Learning Series

While the virtual sessions centred around learning new tunes and being provided with an opportunity to perform them, the video lessons offered in the Virtual Learning Series[12] provided a focus on improving learners’ technical aspects of performance. These videos were provided by guest tutors, specially chosen for their pedagogical knowledge and experience in teaching amateur learners. Tutors played a variety of instruments including the fiddle, button accordion, banjo, and bodhrán. For the majority of the videos, however, students of any instrument could learn something, since in ITM, most tunes can be played on any instrument. Similarly, the stylistic components are similar across instruments, although their technical execution may vary.

The videos ranged from 15 minutes to 40 minutes in duration and followed a common format. Firstly, the tutors introduced the tune and demonstrated its performance at a regular tempo, before breaking the tune down into smaller phrases for students to learn aurally and through visual imitation. Once the basic melody had been broken down, tutors moved on to describing, breaking down, and using various forms of ornamentation (or embellishment), and on variation (how to vary how the tune is played when repeated), as well as outlining instrument-specific techniques.

The following excerpt from Liz Hanely’s tutorial on the tune called “Spórt” highlights an emphasis on aural learning, as is common in ITM,[13] and on developing the use of the 4th finger in fiddle playing:

So, I thought I’d go ahead and teach you the second tune “Spórt” by Peadar Ó Riada, and this tune is a three-part tune in D major, and it is maybe the trickier of those three tunes, so I thought I’d break this one down for you. But first I’ll just play it at a comfortable speed, so you get a sense of the tune—it’s great to be able to hear the tune a bunch [and] get it stuck in your head, maybe be able to sing it, you know—that’s how having that step done first really helps put it into your fingers. [Music] So, we’ll start with the A part, the first part, and it outlines the D chord straightaway. So, it starts on an A, so if we were doing a D major arpeggio D F# A D [arpeggio]

And then the next part starts on the G [plays]. That’s G C# D E. Now I’m using my fourth finger here [to play the note E on the A string of the fiddle] cuz I like it, but you could use your E string. It’s just less string crossings if you can manage that fourth finger. So, let’s play that part again [Music]. (Tune Supply 2020, 0:01:04) In the following extract, fiddle player Heather Bixler demonstrates a strong pedagogical orientation in her foundational course in mastering the rhythmic groove of ITM, something which proves very challenging for novice learners of the music:

One of the most difficult aspects of learning traditional Irish music, especially if you don’t grow up with it, is in the area of rhythm. Rhythm is predominant. You cannot get away with playing anything less than a perfect groove, and it is swung, meaning that all the notes are not the same length. In a reel, note lengths alternate between being long and short. We actually are very familiar with this because it’s the way we speak. Our vowel lengths alternate between being long and short. If we didn’t have this alternating long-short vowel lengths, our speech would sound very artificial. The way we play Irish music then imitates the way we speak, or else is the other way around. We actually don’t know which came first. (Tune Supply 2020, 0:03:45)

A unique pedagogical strength of these videos was the virtual “presence” of the tutors, resulting in interactions which took place between tutors and learners. Some of the tutorial videos were pre-recorded and then broadcasted, while others were livestreamed. In both cases, tutors were “present” in different ways. In the case of Andrew Finn McGill’s tutorial on the tune “Tom Ward’s Downfall,” Andrew livestreamed the tutorial, with around 30 students tuning in live to watch. He followed along with the comments in the live chat box. This resulted in live interactions with learners, with Andrew speaking, and the learners typing in the chat box. This transcript below combines audio transcription and chat transcription, and illustrates tutor-learner interaction following an initial period of around 30 minutes, breaking the tune down:

Andrew [spoken @ 0:34:02]: Do you guys have any questions? I’ll open the floor here real quick for anything that needs clarification, or [things] I should go back and revisit, [I’ll] give you [some] time to put on your picks and your bows and write something there if you choose…

YouTube Live Chat Participant 1 [chat @ 0:34:05]: Do you do the double roll all on one bow?

Andrew [spoken 0:34:32]: “Do you do the double roll all in one bow” … yes, you do [demonstrates]. You do. The last note of the first roll is the first note of the second roll, so it’s not quite a double roll, it’s missing one note, but the point is I would bow through all of that. I’m sort of setting up the next roll.

YouTube Live Chat Participant 2 [chat @ 0:36:13]: It sounded hard at first, but you broke it down beautifully! Thanks!

YouTube Live Chat Participant 3 [chat @ 0:34:24]: Love the tune! Great class! Thanks, Finn! I sound so much better playing along with you. (Tune Supply 2020, video and Live Chat box)

From the perspective of student learning, there was a strong expression of appreciation for the detailed view of musicians engaging in instructional performances. One fiddle student, who describes themselves as an advanced level musician, commented on how her exposure to a variety of guest musicians and the video format of the tutorials benefited her playing:

Mary: I think that also came from hearing the various professionals so closely, cause I couldn’t do that in a [face-to-face] session setting, or maybe even in a class setting necessarily, and having access to a recording that you can use later. Like I said earlier, that really does up your game, you know, when you’re able to pay such close attention, and I think I’m at that level where I’m watching technique. I was also watching their bowing, you know, and me on screen, I’m able to be right next to them in the window so I’m able to really work on that and see how the different techniques are. It has actually been oddly helpful to me in fine-tuning my own [technique].

Peer-to-peer learning was also evident in the live chat box of the YouTube Live learning videos, as learners helped one another clarify what was being demonstrated and explained by the tutor. The following short extract illustrates some peer interaction during the live stream of Anna Colliton’s bodhrán tutorial:

YouTube Live Chat Participant 1 [chat @ 0:26:01]: So, the double down precedes beat 1 of the following measure, right?

YouTube Live Chat Participant 2 [chat @ 0:26:18]: Yes

YouTube Live Chat Participant 1 [Chat @ 0:26:35]: Depending on where the triplet is placed in the measure. (Tune Supply 2020, Live Chat Box) These rich extracts illustrate that tutors employ a range of strategies to establish their presence. Tutors were viewing their videos, reviewing them, and watching and experiencing them from the viewpoint of the musical learner, providing clarifications and answering learners’ questions. In the livestreamed tutorials, tutors could respond to learners’ comments in the chat boxes, talking directly to them, reviewing the questions, answering them, and—critically—demonstrating the technique under question.

Post-pandemic, the virtual learning series and the virtual session series continue to be an invaluable resource for asynchronous learning in ITM. This is evidenced by the continuing increase in the number of views on the videos, and by the positive remarks that continue to be left in the comment sections of the videos.

Musical Learning and Social Participation

Potential musical learning in Mary O’s virtual session included learning tunes and expanding repertoire; gaining insights into artists and historical knowledge about the music tradition; increasing familiarity with and execution of diverse stylistic interpretations of ITM (including technical devices such as ornamentation, groove, harmonic accompaniment, and creative devices such as variation and improvisation); and gaining insight into the hotspots of ITM activity (concerts, classes, where musicians are based) within the diaspora and beyond. While the videos in the virtual learning series provided a focus on instrumental technique, the virtual sessions focused learners’ attention on the performance of existing repertoire and acquisition of new repertoire.

The purpose of the session and the resultant learning for participants varied according to their previous experience and skill level. An advanced player mentioned missing the chance to learn new tunes aurally at their usual face-to-face session, finding the virtual session a valuable substitute that offered the “pushback” or challenge of learning and playing unfamiliar tunes. The virtual sessions facilitated real-time aural learning as well as post-broadcast review, enhancing familiarity with the recurring core repertoire, and enabling enriched participation in subsequent sessions. Another learner, who was not part of the original community of musicians who attended Mary O’s face-to-face session in Manhattan, reported that she acquired the core repertoire of the virtual session through regular participation; this virtual engagement facilitated her full musical participation in the in-person sessions at Mary O’s during a visit to New York City post-pandemic.

Learners of a more novice and intermediate level recounted that they played along with the tunes that they already knew during live broadcasts, but that in learning new tunes, they relied on noting the tune name, so that they could learn the tune from a combination of reading its notation and rewatching the videos post-broadcast. One learner shared his experience:

Jack: That’s the thing in a session. If I hear a tune, I’m not good enough to be able to just, you know, pick it up [learn it aurally] by the second or third round. I need quite a bit longer to learn something. So, what I’ll do in a, in a like a pub session is, I’ll just make a note, you know, I’ll ask what the tune name was, and then I’ll go home and learn it so that I can play next time. And that’s pretty much what I did in this case [the virtual session], you know, except I already had the recording of it right there… So, you can go back and listen over again and play along.

Learners also appreciated the slower pace and pedagogical focus of the videos in the learning series, facilitating the learning of more complex tunes through detailed guidance:

Jack: The lessons were helpful. Yes, because frequently, even if I slow it down, if a tune is too complicated, I’m not going to pick it up. It’s just too much for my skill level. So, it was helpful to have someone walk me through… Okay, so like “first finger here,” you know… For simpler tunes, I would just play it by ear, for more complex ones [I] would need the extra help of walking me through it.

The video format of the virtual session also allowed valuable aural and visual access to the playing of a range of renowned Irish traditional musicians, from which learners benefited:

Anne: And the quality of their musicianship too, I usually wouldn’t hear it in a pub surrounded by other musicians. But here … Kevin Crawford or Cillian Valley or Matt Mancuso or John Redmond or any of those playing just purely by themselves. [It] was gorgeous and special. And that was a slice of Irish trad that, frankly, we would never get to hear except in a like concert setting. And we were encouraged to play along or learn with them and that. I think it upped all of our games. It certainly did for me. It made me appreciate them, made me hear the music in a different way.

While musical learning was an important dimension of the motivation to participate, the following excerpt demonstrates that the social connection was equally important:

Anne: I definitely participated live. I didn’t miss a single one. The isolation in New York City was profound. And then once a week, this series came on my screen. I plugged in, I put [in] the earphones, I got the fiddle out, I tuned up, I rosined up the bow, I was ready, and I was typing in the comments and playing along, and it felt so good. It felt so good to be with everybody altogether… I was concerned about the isolation … we were all going to be okay for the next hour and a half.

The social connection that the virtual sessions provided is of significant note. While musical learners could not see or hear each other, learners could still interact in the live chat box with each other, with the session hosts, and occasionally with guest musicians. The virtual session hosts are skilled at creating dialogue, and thus fostered engagement and social participation with their viewers. This was achieved through several mechanisms, including carefully planned topics for exploration as well as spontaneous conversational exchanges, or “banter.” Hosts “talk” to viewers as well as to each other as a way of opening up avenues for exchange. For example, they ask what kind of week viewers had experienced; and enquired as to what everyone was “drinking,” mimicking the conversational exchange in a face-to-face session. They commented on what other musical activities they’d been up to—which, during the pandemic, often comprised of online teaching and concerts they’d partaken in—and gave details of upcoming gigs. In this way, a network was created between the virtual session and other current ITM activities. The hosts frequently acknowledged specific viewers during the session, particularly if they were familiar with them as fellow performers, students, or from previous online events.

The hosts also shared pre-submitted stories, photos, videos, and memes from viewers on various topics, including on the pre-selected “theme of the week.” For example, the pre-selected theme of “Ireland and other Green Things” was shared ahead of the live broadcast, and resulted in viewers sending in photographs of green nature scenes, of themselves wearing green clothes, of various green objects, etc. This enhanced engagement with the virtual sessions. Viewers felt invested in the livestream and part of a wider community and saw it as more than an opportunity to just play tunes: it was a meaningful social gathering with music at its centre. The hosts also shared any pre-recorded videos of viewers’ musical performances that were submitted. Although they ostensibly remain “invisible” and audibly “muted” during the livestream, they were present—or presented—through the broadcast of their submitted artefacts. The hosts also fostered interaction through playing games. Caitlin shared details of one particular game they played during a virtual session:

Caitlin: We’ll say like, “Okay, tell us in the chat your favourite name of a tune that doesn’t actually exist. And like the crazier, the more creative, the better.” So, people will start chatting away. And then the cool thing is we can bring the winner’s comment on screen in real time, so it shifts over. Everybody sees it with the name and then we can say so and so, you won the contest. Send us your email. We’ll send you a t-shirt. There’s a lot of interaction between people and we will reply in real time to people’s comments. So, like if they ask a question like, what key was that tune in, we’ll say, oh yeah, Sarah, that that tune that we just played was in G. And so, it does feel to the watcher, like there is some actual communication, well there is, like it is in real time, basically.

The weekly virtual session also included the recitation of a poem, created about one of the guest musicians. This was a practice that was retained from Mary O’s face-to-face session.[14]

While the interaction here describes the synchronous live virtual sessions, email communications to the session hosts included fellow professional musicians complimenting the quality and production values of the virtual session; and learners, providing feedback (e.g., how much they enjoyed playing along; how they found it useful to be able to learn the tunes beforehand; how they used the resource after the live broadcast; making requests for certain guest musicians—which were frequently honoured; requesting certain tunes be performed in future sessions—again which were often honoured), and sharing their performance videos.

Roles and Identities

Participants in the virtual session belong to three distinct groups: the host musicians (Caitlin and Chris); the invited guest musicians and tutors (who differed each week); and the audience or viewers of the livestream, who can adopt a number of roles, from passive lurker (see Kozinets 2015) to active performer and learner. While each individual may be identified by their role, they may assume different identities at any given time. For example, Caitlin’s role is host of the session, but her identity can shift between presenter, performer, and teacher during the livestream. Offline, she also assumes the responsibilities for content creation, communication with musicians and students, and management of the business as a whole.

For viewers of the virtual session and virtual learning series livestreams, participation can be considered on a spectrum, from more passive to more active (see Figure 2 below). The discussion which follows considers the more active forms of participation in the context of Turino’s conceptualisation of fields of artistic practice (2008); and as participatory culture, based on Jenkins et al.’s concept in new media education (2009). The discussion also illuminates the ways in which the virtual session enabled musical, pedagogical, and social continuities.

Figure 2. Roles and identities in the virtual session.

Figure 2. Roles and identities in the virtual session.

Discussion

Turino

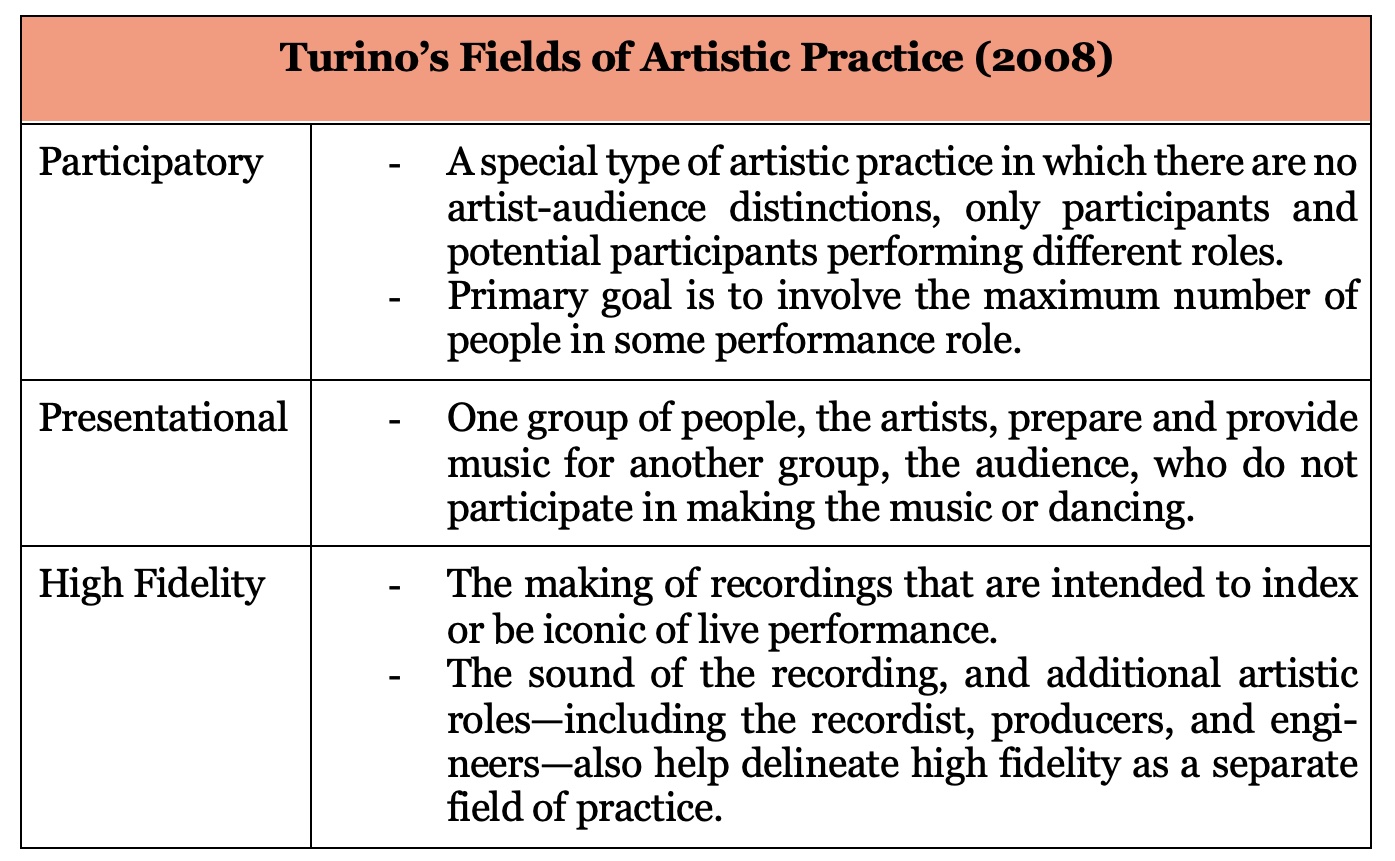

When considering Turino’s characteristics of participatory musical practice within the context of the virtual sessions, we can firstly note that viewers have the option to participate in any combination of playing along, listening, or engaging socially. In the case of the learning series, learners can actively try to imitate a tutor’s playing. There is no limit to the number of people who can play along. However, the virtual session also displays characteristics of more presentational and high fidelity performance practices (Turino 2008). For instance, there is a clear distinction between the hosts and guest performers versus the viewers, although hosts/guests perform in the belief that viewers have the potential to play along with them. Hosts and guest musicians prepare for the session by selecting tunes, learning tunes, practising tunes, and recording video and audio content. Since most guest musicians submit pre-recorded videos, this represents a high fidelity musical practice. Therefore, music making may be understood as different fields of artistic practice (Turino 2008) depending on an individual’s role.

Figure 3. Turino’s fields of artistic practice.

Figure 3. Turino’s fields of artistic practice.

Jenkins

Again, the different roles of participants in the virtual session determine how their experience resonates with Jenkins’ concept of participatory culture. All criteria are met for all roles, even if in a limited capacity.

In considering low barriers to artistic practice, all ITM learners can practice by playing along with the virtual sessions and virtual learning series. Strong support is provided by the hosts for guest musicians and tutors to share their creations—performances and tutorials—with others. This opportunity is extended to viewers, albeit with a more limited uptake. The combination of the virtual sessions, the virtual learning series and the surrounding discourse presents a strong pedagogical framework, which fosters inclusion and facilitates participation within an informal mentorship, although feedback is mostly absent. According to Caitlin, participants communicate that they feel they “belong” and that their musical and social contributions matter—with some viewers sharing that they feel they are the most important participants (and thus, the virtual session could not happen without them). Social connections are evident in the chat box exchanges which facilitate peer learning; some of these are existing connections which are maintained through the online space, while others are nascent new connections.

In addition, forms of participatory culture articulated by Jenkins et al. include expressions, collaborative problem solving, affiliations, and circulations (2009). All these forms are represented in the virtual session to varying degrees depending on participants’ roles and skill levels. In terms of expressions, the virtual session is a new creative form in itself, which also includes the remediation[15] (Bolter and Grusin 2000) of previous digital media. In the performance of the music, improvisation is minimal, according to oral tradition norms, and limited by the skill level of the musicians. Collaborative problem-solving is illustrated through participants adding timestamps for other users to enhance the virtual sessions’ value as a learner resource, contributing to the development of a collective intelligence[16] (Jenkins 2006; Lévy 1997). Growing affiliations are evident, and connections are made to face-to-face events, but there is a lack of a permanent virtual “space” outside of the virtual session and learning series livestream slot for continuing their development. Circulations are illustrated in how the virtual session acts as a nexus to connect musicians and their practice, and in how it serves to make connections between different ITM resources across various websites and modes of representation, including audio, video, and notation.

Figure 4. Participatory culture as defined by Jenkins et al. (2009).

Figure 4. Participatory culture as defined by Jenkins et al. (2009).

Having presented a significant range of data, and analysed it under several themes, the following discussion considers how the virtual session provided musical, pedagogical, and social continuities for its range of participants.

Musical Continuities and Discontinuities

The virtual session provided continuity for professional musicians, such as the hosts and guest musicians, by providing them with a performance platform and income when live gigs were no longer viable during the pandemic. For music learners, the virtual session was a direct continuation of the regular Mary O’s session, which many students had been using as a performance outlet for showcasing their developing musicality.

While Mary O’s face-to-face session relied on local musicians or musicians who were visiting New York City to lead the session, the virtual session opened up the possibilities for participants to hear Irish traditional musicians from further afield, including Ireland. This allowed participants to hear the regional and personal styles and interpretations of a wider selection of musicians than those they might hear regularly week to week. This demonstrates the benefits of extending synchronic performance ensemble practices beyond physical spaces to the mediated (Cayari 2018). The virtual format also expanded and diversified the viewership by attracting students and fans of the guest musicians.

Mary O’s session was transformed from a musical gathering rooted in the locale of the Irish diaspora in Manhattan, to one now located virtually. For both those who had transitioned from the face-to-face session and those who just joined the virtual sessions, the hosts worked hard to (re)create a sense of intimacy, familiarity, and continuity from week to week to foster a sense of belonging. Participation in the virtual session by both professional musicians and learners constitutes “cultural phenomena surrounding music and emerging ways of being musical,” with the continued—yet transformed—integration of music and participatory culture into their lives (Tobias 2013, 29).

In terms of musical discontinuities, two practices presented challenges. Firstly, the spontaneity of the regular face-to-face session was compromised in the move to the virtual format. In contrast to the face-to-face session, in which repertoire is chosen in the moment, the hosts—displaying their performer identity—felt that pre-selection and sharing of all tunes to be performed on a given night detracted somewhat from their musical experience. Secondly, guest musicians were encouraged to perform only common tunes at slow speeds in their contributions, but some expressed frustration at these limits, as they felt their individual musical identity was best reified through playing more diverse repertoire at greater speeds, indicating that they saw this as a performance outlet, rather than a teaching one (and that they were perhaps frustrated by the lack of performance opportunities at the time). The hosts made the decision to keep both slow and fast practices to maximise viewer appeal and participation. In this way, the virtual session had to achieve a delicate balance in the pursuit of success as both a business and artistic venture: the success of the virtual session, and thus its future viability, relied on keeping viewers happy. Viewer happiness appeared to be anchored around their successful participation, with the virtual session therefore presenting a somewhat balanced pedagogical and musical orientation, providing a platform for both performance and learning.

Pedagogical Continuities and Discontinuities

The virtual session, virtual learning series, and the development of associated resources, such as the “Cliff Notes” document, provided students with a structured environment within which they could set weekly goals for their musical learning. It is a clear example of “media convergence” (Jenkins 2006), demonstrating “multiple systems that coexist where content flows fluidly through ongoing processes” (Tobias 2013, 34; see also Jenkins 2006, 282), and exemplifies Waldron’s concept of “informal learning music 2.0” (2016, 93).

While Lange defines three distinct types of YouTube tutorial videos (2018), each with a particular focus, the virtual sessions and the virtual learning series videos often combine these foci. The first of Lange’s tutorial types, which focus on skill development, are demonstrated through the teaching of stylistic components of ITM, including ornamentation and variation, in the virtual learning series. The second type, performance or demonstration tutorials, are exemplified in both the virtual sessions and the virtual learning series, where professional musicians and teachers perform for the students. The third type of tutorial, focussed on the general transmission of knowledge, are embedded in all resources, as musicians and teachers share their knowledge of tune names, origins of the music, composers, performers past and present, associated places, and so on.

The desire to continue participating in the virtual sessions sustained students’ engagement with other opportunities for online learning—such as the virtual learning series—and with their independent practice. “Purposive listening” (Green 2002, 23–24) and “purposive viewing” (Lange 2016, 104)—that is, the active engagement with content intending to learn and improve one’s own practice—is evidenced in the live chat box of the virtual learning series videos, and in participants’ efforts to grapple with and imitate what is being demonstrated in the tutorials. Learners also contributed to the virtual session’s success as a learning resource, through “purposive commenting” (Lange 2016, 104) by time indexing tutorial videos and providing peer learning support.

Learners reported finding the time indexes useful, as many, being of a novice-intermediate standard, could not learn the tune aurally “on the fly” during the live broadcast. They used the time indexes as a shortcut to help find and replay specific tunes they were interested in learning. Learners’ contributions to these learning resources act as a signifier to other learners as to the value of the content, resulting in the resource becoming a “socially encoded” artefact (Lange 2018, 5).

In presenting the virtual sessions, Caitlin also made reference to upcoming online workshops she was teaching for various music schools around the USA, increasing awareness of further learning opportunities. Some tutorial videos were taught in Spanish by an Argentinian Irish traditional and Celtic musician, which also diversified the potential audience. Given the demographic of New York City and widespread use of Spanish worldwide, this facilitated expanding participation.

The development of the virtual session as a nexus of learning created a network which linked professional resources and user-generated content across the Internet on the topic of learning ITM. These included tune databases, discussion forums, blog posts, concert schedules, music streaming services, videos, audio files and notation. This synergy created through the investment of all participants in the virtual session contributes to the continued development of a digital collective intelligence (Jenkins 2006; Lévy 1997) focussed on the learning of ITM.[17]

Learners also provided feedback on the virtual sessions on a weekly basis to the session hosts. These included requests to play at a slower tempo, to include more common tunes, and to cover specific technical skills in the virtual learning series. These requests were honoured and illustrate that informal learning through interactivity may occur bidirectionally and lead to the “flattening” of pedagogical structures, such that tutors and learners learn from each other by interacting at a variety of levels with the tutorial and its surrounding discourse (Lange 2018). This also echoes Jenkins’ observations that “the political effects … come not simply through the production and circulation of new ideas … but also through access to new social structures (collective intelligence) and new models of cultural production (participatory culture)” (Jenkins 2006, 246).

The pedagogical discontinuity here, related to the common challenges in online group teaching, is that feedback on one’s performance is missing. While the function of the ITM session (face-to-face or virtual) is not to directly teach or provide constructive feedback on one’s performance ability, both self-assessment and informal feedback from others in this context can be invaluable for one’s musical development.[18] Caitlin, drawing on her experience teaching online for the Irish Arts Center, as well as in providing the learning platform of the virtual session, is acutely aware of the pedagogical shortcomings, but conversely also highlights how adult, amateur learners appreciate the elimination of the commute to music lesson, having a recording of an online lesson/session, and the safety and anonymity provided by remote instruction:

Caitlin: Well, one of the things in New York here, so I teach at the [Irish] Arts Center. It’s been online for a year. I was dreading it going online, but one of the things that people like is that they don’t have to travel, say, forty-five minutes or an hour on the on the subway to get to the class. They can just sit down and play. They love that the class is recorded so they can go back later and watch it if they have to miss it. They’ve told me that they like that, that nobody else can hear what they’re doing because they’re all on mute, right? So, I’m very aware, like in real life, especially for adult beginners, they are very self-conscious and worried about their sound. If they can sit there and they know I can’t hear them and the other people can’t hear them, they can do whatever they want, and it’s freeing to them to be able to do that. To me, it’s alarming because I can’t hear them, and I can’t tell them when there’s a problem with what they’re doing. They are generally too fearful to turn their microphones on, so I can’t even get at them. What service are you providing as the teacher when you’re instructing somebody but there’s no feedback from the student as to whether anything’s going across? It kind of becomes more like a TV show at that point. So, yeah, I think the students like the anonymity of it, and the ease of it, that they can just sit down and do it. They’re less scared, less fearful, all that sort of stuff.

Students are not unaware of the challenges for teaching and learning presented in this context of music transmission. When asked what kind of progress he felt he had made as an Irish traditional musician as a result of his engagement with the virtual sessions, one student shared:

Jack: Yeah, it’s hard to say. I certainly wasn’t getting feedback from anyone because I wasn’t playing with anyone. I suspect that my … well, I don’t know if I got better. I learned more tunes, but I don’t know if I got better. So, I think really the goal was maintenance [my emphasis].

Jack shared that he looked upon the virtual sessions as providing the opportunity and motivation to maintain his practice of Irish traditional music during the pandemic, expanding his repertoire of tunes, with the hope and expectation of returning lesson-based learning featuring constructive feedback on the more technical aspects of playing post-pandemic.

While the lack of feedback may represent a deficit in this format of online learning, direct pedagogical instruction on instrumental technique is not the only learning focus or opportunity. Learners might simply use the video to identify future tutors and collaborative learning opportunities (Lange 2018), or to orient themselves within the virtual ITM landscape. In addition, there are opportunities for more organic interactive learning, outside the specific directed intentions of the tutorial videos, in the “everyday digital environments of sociality and play between people” (Lange 2018, 2).

Social Continuities and Discontinuities

Waldron, in citing Turino’s work, contends that “for successful participatory music making to happen, it must be socially situated and culturally contextualized in community” (Waldron 2016, 86). The virtual session was originally created to provide a digital space for the community of learners who attended Mary O’s weekly session to maintain their musical practice and social interaction. For these learners, the virtual session provided social continuity on a basic level through interaction in the chat box, with learners using handles recognisable to others in their community. Learners cited that they were attracted to the interactivity, in addition to the structure and familiarity, offered in the virtual session. The audience of the virtual session grew well beyond the original attendees at the face-to-face session, with interaction within the chat box evident between people from around the world.

The virtual session hosts fostered engagement through a number of deliberate strategies including the request for the submission of artefacts, participation in games, and so on, which encouraged further interaction. The virtual session became a central thoroughfare in the online landscape of ITM, with musicians and learners contacting the host to put them in touch with others they had encountered online.[19]

While this fundamental level of social connectedness illustrates rich possibilities for interaction, it is perhaps more fascinating to acknowledge that the social continuities supported and fortified the musical and pedagogical continuities: these continuities are not isolated phenomena. Learners referred to it as a “very personal way of learning music” and that this “really helps in learning in that it draws you back.” The virtual session demonstrated the potential to provide peer-to-peer connections that facilitate socially oriented, playful modes of learning (Lange 2018).

The virtual session also served to democratise access when compared to the experience at a face-to-face session. In a face-to-face session, the host—i.e., the hired professional musicians—sit in a central position, with the most experienced and socially familiar musicians near them, and the least experienced on the periphery. Opportunities for interaction between amateur and professional musicians physically placed at the core would be very limited. In the chat box of the virtual session, viewers of any musical level—and perhaps even no previous musical experience—could pose questions for, and chat with, the host musicians and guest musicians, flattening the hierarchy featured in face-to-face socio-musical interactions. Through our interview exchanges, Caitlin came to realise the potential and significance of the virtual session in disrupting the physically imposed hierarchy of the face-to-face session: