TIM PALMER

Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance, England

PAMELA BURNARD

University of Cambridge, England

DAVID BURKE

Bath Spa University, England

February 2025

Published in Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 24 (1): 7–47 [pdf]. https://doi.org/10.22176/act24.1.7

Abstract: This paper offers an invitation to higher music education communities to think differently about the significance of the connections between music and play. We highlight the many texts that articulate these connections and draw together a speculative ontological claim that all musicking is an enactment of play. In other words, we ask how “musicking-as-play” might be a catalyst and an orientation for pedagogic innovation in higher music education. Adopting Huizinga’s concept of a “play force,” this philosophical study reveals multifarious ways in which play is enacted through musicking, leading us to coin the new term “musicking-as-play.” “Musicking-as-play” recognizes, values, and nurtures the particular play force that manifests with/in music genre performance practices. We thematically explore play’s manifestations in the materiality, relationality and transgressionality of a selection of genre practices, specifically heavy metal, Western art music, and jazz. We put forward “Musicking-as-play” as a new concept that acknowledges the entanglement and interrelationship of materiality, relationality, and transgressionality as domains that are fundamental and present within acts of “musicking.” Subsequently, we speculate on what “musicking-as-play” might invite for higher music educators.

Keywords: Play, musicking, musicking-as-play, materiality, relationality, transgressionality, genre

A heavy metal band plays at a rock festival to fans wearing their t-shirts and who sing along the ironic words to their best-known songs. A classical soloist receives applause after a concerto performance in which they tried to express a feeling of freshness to the interpretation whilst staying firmly within accepted interpretative parameters. Members of a jazz quintet interact subtly with the soloist, who challenges the audience with silences and temporal shifts within a well-known melody. This article theorises a connection between these and similar events in order to offer a speculative new discourse of “musicking-as-play” for music education in general and higher music education performance studies in particular.

The relationship between music and play remains under-theorised in music education. The play literature regularly cites music as an example of play, but whilst there is increasing interest in play by music educators there is a need for more research that uses a wide range of the play literature to develop a rich theorisation of how play might manifest in musical practices. In this article we present of the concept of “musicking-as-play” as a speculative lens through which to further understand, and perhaps even undo, deeply internalized genre practices. Whilst discourses of education in society are increasingly critical, dynamic, and fluid, performance practices that are taught in the teaching studio and higher education classroom too often have remained static, rigid, genre-bound, and resistant to change. Since play has the potential to disrupt that inertia and to mobilize transformative possibilities within and between higher music educative processes, we consider why and how variegated and complex play matters for music education in general, and specifically for advanced performance education.

In order to address these questions, we begin by drawing from play theories, performance genre theories, and musicology to make the speculative claim that “musicking,” defined by Small (1998) as including all the peripheral behaviours associated with performance practices, is a form of play. We explore how “musicking-as-play” might be imagined through three key concepts of “materiality,” “relationality,” and “transgression.” The second section constructs examples from three different genre practices, namely heavy metal, Western art music (WAM), and jazz in order both to support the core claims and to illustrate how these claims might manifest in professional practice. We conclude with an exploration of what “musicking-as-play” might mean for music education, inviting a critical examination of implications for frameworks of power, identity, and social justice in the classroom.

I. Shifting Perspectives: Play and Music

We acknowledge our specific viewpoints as British musician-academics, all practising and professional musicians with overlaying geographies and backgrounds. These identities mean that we look at and “diffract” (Haraway 1992) musicking-as-play from particular angles, certainly informed by privilege. Potentially such privilege might contribute to an affordance for play experiences that others do not enact or feel, and we recognise that play has a personal and performative phenomenology that we uniquely tailor to our own situated encounters with the world.

Whilst we are writing from a praxial standpoint (Elliott 2005), we are seeking to draw in a wide range of literatures to make our arguments. We are not specifically taking a post-humanist stance, but our thinking has been partly influenced by post-humanist principles and writers. It is our view that different and diverse theorists, and scholarship from different traditions can overlap, combine, and interfere with each other in diffractive ways (Haraway 1992). Thinking with diverse theorists generates new possibilities and provides the potential to think otherwise, to think differently about play and music education. We are encouraged by Barad (2014) to break out of the usual and to trouble the unilinear ways in which we historically hold firm to particular traditions of enquiry when she writes of doing justice to how new ideas materialise differently in diffractive collaboration with others. In collaboratively challenging ontologies, we conduct this enquiry by thinking with and through concepts, interested in research “that might produce different knowledge and produce knowledge differently” (Lather 2013, 635) in the search for reconfiguring metaphors and discourses that have the potential to confront and disrupt ossified practices.

We are developing the concept of “musicking-as-play” as a new ontological[1] proposal. This connects with the increased attention to ontological study in music in the past decade from a variety of stances,[2] not least as a result of the “performative turn” in musicology (Cook 2013), which seeks to reappraise the role of the performer in contributing to musical meaning. From a research perspective there has correspondingly been a return “back to the things themselves” (Husserl 1970/2001, 168), which in this case, means back to the embodied ontology behind the experience of performing or connecting to music. Performance theorist Peggy Phelan (1993) argues that “only rarely in this culture is the ‘now’ to which performance addresses its deepest questions valued” (146); in this present study, we aim squarely at what she describes as the “maniacally charged present” (148) in performance in order to re-theorise the phenomenological experience of musicking-as-play. This drives us towards the proposal that musicking has a range of ontologies,[3] but that it always has within it an ontology of play, at times weakly and at other times strongly, but ever-present. Through this lens, musicking is considered a form of play. Thus, a range of genre-specific performance practices can be examined to identify the multiple characteristics of this one ontological lens, musicking-as-play, in order to inform higher music education performance studies in particular, and music education in general.

As many writers have argued, play has proved a slippery concept to clarify. As long ago as 1993 performance studies theorist Richard Schechner suggested that “maybe scholars should declare a moratorium on defining play” (24). The academy has instead moved beyond defining and toward refining our understanding of play’s characteristics and forms, often through lists and descriptions of traits. These range from surface characteristics such as Eberle’s (2014) five basic qualities of play (purposeless, voluntary, outside the ordinary, fun, and focused by rules) to more subterranean explorations, such as play’s adaptive variability (Sutton-Smith 1999, 253; van Vleet and Feeney 2015), its appearance at different scales from micro- to macro-levels (described by Marks-Tarlow (2010) as its “fractal” qualities), and its representation through states of mind and moods rather than through action (Gray 2013, 139; Karoff 2013). Henricks (2015) argues that play comes into relief in relationship to three other behaviours: work, ritual, and self-other-world bonding, or communitas. In relation to these, play is the only one that is both transformative, seeking to assertively interact with the environment, and consummatory, in that it commits to “bounded moments” (Henricks 2018, 138) with an intrinsic process orientation that loses track of time.

Central to much writing on play is the idea of a “play force” that motivates all culture and life (Huizinga 1949/2016; Shields 2015); play is perceived as a “transcorporo-reality”[4] (Alaimo 2012) that moves within and between non/human bodies. “Play has its own essence, independent of the consciousness of those who play … the players are not the subjects of play; instead the play merely reaches presentation through the players” (Gadamer 1975, 103). In the well-known text on play Homo Ludens Huizinga (1949/2016) argues that culture is a crystallisation of the play force: “civilization arises and unfolds in and as play” (foreword), and the wider play literature claims that using cultural difference, self-identity is generated through relationship with/in community (e.g. Bell 2008; Brown 2009; Dissanayake 2017; Henricks 2015; Sutton-Smith 1997). This moves the argument beyond notions of art as “playful” to the concept that all art is play: play is “the mode of being of the work of art itself” (Gadamer 1975, 102). This is a personal as well as a general statement: art engagement is our play no matter how well we make it or how peripheral is our relationship with it. The act is central: for Gadamer (1975) play does not exist in an art object (111), but rather in its performance “as we see most clearly in the case of music” (115).

This concept of a “moving force of play” underpins and conjoins musicking and connects disparate genre practices. At times this force is manifest and free flowing, but all too often in music education it is subterranean, faint, stagnant and ignored. However, we maintain that for music to fulfill its human functions the presence of the play force has to be recognized, nurtured, and valued within it as it motivates the play of sounds but also of much more, including meanings, materials, identities and relationships. Thus, our conceptualisation of an ever-present play force in music connects with Small’s concept of musicking in that musicking-as-play includes domains well beyond the making and hearing of sounds and establishes relationships in play between all participants in a cultural event. Just as Small (1998) argues that the person “who takes tickets at the door or the hefty men who shift the piano” might be musicking (9), so might they be motivated by the play force to contribute to cultural acts as play.

Framing the Concept “Musicking-as-Play”

There is a wealth of writing on early years, playground, digital, and improvisatory play in music, but this present article offers a new perspective in looking at play’s underpinning of music-making across varied genre practices in relation to higher music education. The concept of performative play underpins much performance studies literature (e.g., Schechner 2020); within musicology there is less interest, although Moseley’s (2016) book on ludo-musicology is a significant contribution, as is Dorschel’s (2018) chapter on the play ontology, even whilst it cautions only a tentative stance. Music education has a few valuable texts that discuss play, mostly from the WAM tradition, for example Addison (1991), Green (2011) and Swanwick (1988), but these three all take the viewpoint of single play scholar. Todd and King (2022) articulate play as an “x-factor” element of peak performance, and Stewart Rose and Countryman (2021) use the term ‘musick-play’ in relation to the roles of music in young people’s lives, predominantly looking at informal rather than formal learning.[5] In contrast, Stubley (1993), Reichling (1997), and Csepregi (2013) offer views closest to ours, arguing that play is a universal underpinning of music; however, the latter two have a strong WAM orientation, and whilst Stubley is careful to apply arguments across contexts, she provides little detail as to how this might occur in practice.

Praxial philosophy points to a way of being musical that is rooted in humanity and agency; the idea that “music is something that people do” (Elliott 1995, 39) maps onto Huizinga’s (1949/2016) concept of play as a universal facet of human existence. Bowman’s focus on somatic knowledge (2004) for example, aligns with the centrality of the body in play that is identified by scholars such as Brown (2009), Power (2011) and Henricks (2015), who argues that “play is always a biomechanical affair” (116). Moreover, Regelski’s (1998) arguments on praxis in music education makes it clear that it is a situated, temporal and constantly variable form of judgment-making, a “personal, individuating, self-actualising, and even idiosyncratic matter” (30); this focus on autotelicism in service of a change-focussed encounter with the world is characteristic also of many descriptions of play.

A few writers from the praxial tradition have specifically connected music education to play. Kratus (1997), for example, argues for the importance of a play/process orientation alongside work-centred/product orientations. Likewise, Jorgensen (2011) states that an “emphasis on the present, on happiness, enjoyment, or pleasure in the moment … make musicking more a matter of play than work” (127). Bates (2021) meanwhile brings many of these themes together in a reaction to the neoliberalism of much modern education by arguing that play offers an alternative route to personal fulfilment and social emancipation through music.

Clearly, play has social justice implications in music education that demand a closer look at what play looks and feels like in music performance practices. The questions that inspire our thinking throughout this study are:

- How does advancing Small’s concept of “musicking” to “musicking-as-play” promote the inter-relationship of play, learning and performance in music?

- What are the generative possibilities for speculating on a new ontology of “musicking-as-play” as exhibited between and within diverse music genre practices?

- What, then, are the implications for higher music education performance studies of a new ontology of “musicking-as-play”?

By discursively exploring together our own genre-specific performance practices through the lens of play we identified three imbricated concepts of “materiality,” “relationality,” and “transgression.” Through them we seek to illuminate “musicking-as-play” in order to inform higher music education performance studies.

(1) Materiality of “musicking-as-play”

Within the play literature it is argued that play is “deeply rooted in physical and material instantiations, in objects that carry part of the meanings of the activity, that help it exist and take place, be shared and be communicated” (Sicart 2014, 47). In play, “material objects … function as key operators” (Talu 2018, 81).

The possibility of thinking of play and musical materialism, the play embodied within sound and silence, continues to be at the forefront for those who research the material objects of music-making and the materiality of musical experience (Sergeant, van Elferen, and Wilson 2020; Wilson 2021). In her book Vibrant Matter Jane Bennett (2010) identifies the vital “thing-power” of objects. The concept of thing-power “gestures towards the strange ability of ordinary, man-made items to exceed their status as objects and to manifest traces of independence or aliveness, constituting the outside of our own experience” (xvi). Thing-power emerges from within materials as a presence that acts upon us. Bennett refers to “the capacity of things … to act as quasi agents or forces with trajectories, propensities, or tendencies of their own” (viii). Furthermore, Bennett suggests that “we are vital materiality and we are surrounded by it” (14). Materials are a source of action and play, as observed whenever instruments are laid out in a classroom of young children: they can make demands through their specific characteristics to provoke in multiple and playful ways. Things come to matter as cultural and playful formations, extending meanings through connecting between-across-with multiple senses (Massumi 2002).

As musical instruments are played, materials move and form alliances with other materials; through their playful entanglements with each other, bodies, instruments, spaces, and sounds become material partners. The vital materiality of play is thus conceived as active and forceful, and the body is centrally imbricated: “in manipulating music, we simultaneously manipulate not only the environment but ourselves” (Krueger 2015, 52). As such, performers’ bodies are not taken as isolated from the instruments with which they engage, and objects are “transformed and invested with new meanings that reflect and assert who we are” (Attfield 2020, synopsis).

The unpredictable material intra-actions that shape musicking are inheritances of the “play force” in action. The performativity variables identified by Kartomi (2014) as “persona, musicality, talent, giftedness, competence, interaction, improvisatory practices, cueing, intersubjectivity [and] entrainment” (197) offer a starting point, but can be added to by music’s enfolding of sonic, spatial, and material relationships. Musicking-as-play is characterised by the emergent materiality of sounds and relations that arise from the messiness of surprises and new possibilities inherent within the materiality of music-making, musical experiences, and musical objects.

(2) Relationality of “musicking-as-play”

Play is deeply relational in character, and a number of writers, including Sutton-Smith (1997) and Henricks (2006, 2015), develop notions of play as identity-forming both in relation to and within community. Indeed, Henricks (2015) argues that community-oriented behaviours are difficult to distinguish from play (58), since play is a “social laboratory” (162). For him, play has “fields of relationships” (71) through the patterns of interaction with the physical environment, body, mind, cultural, and social; all of which, we maintain, are enacted through music. This view is supported by Cross (2009): “music has all the attributes of a communication system that is highly adapted to facilitate the management of the uncertainties of social interaction” (190). Dissanayake (2017) offers support, maintaining that relational play is rooted at the start of life in the mother-infant dyad and enacted partly through music; she posits that culture emerges from this foundational intrapersonal connectedness. This emerging play-resonance (Alcock 2008, 20) between self and other orients individuals in social space (Marks-Tarlow 2010) and extends to choices in interpersonal action and interaction (Henricks 2015, 23–25), to self and world (van Leeuwen and Westwood 2008, 153), and even to self-universe orientations (Sutton-Smith 2008, 122). Thus, the self both emerges and is identified through play, and this is recursively true for our understanding of play as well: Sutton-Smith (1997) writes that “the important issue is that play be explained in terms of that relationship between self and play, not in terms of extrinsic issues” (187). How we understand play is affected by our relationship with it, a relationship that is directly affected by our self-concept, which in turn is mediated through self-other play-relations.

(3) Transgressionality of “musicking-as-play”

Play’s strong element of relationality permits play both within and with social conventions. Transgression of social norms has been repeatedly connected to play, often associated with the practice of carnival, in which “all conventions and established truths” are suspended temporarily (Bakhtin 1936/1984, 34). Sutton-Smith suggests (1997) that “the greater the frivolity, the greater the transcendence of the common writ,” with play offering the potential to “transcend reality and indeed mortality” (212–213). Similarly, Sicart (2014) describes the “symptom of freedom” (4) available during carnivalesque play, but maintains that moral conventions are “still present, so we are aware of their weight” (5), even during periods of apparent unruliness. Clearly, there is an ambiguity at work in transgression-focused play, which offers all groups, regardless of their available power, opportunities to assert control (even through the use of chaos) over social spaces. By this we infer that musicking’s inherent transgressive affordances do not imply that all play is “good play” but rather that transgression is a phenomenon that comes into being in the liveness of performance and its peripheral behaviors.

Musicking-as-play is transgressive because choices operate in relation to particular rules, within and with the sociality of sonic practices in diverse music genres. Scholars have noted a relational ambiguity evident in transgressive music-making. For instance, Boeskov (2018) argues that “social music-making that at one level allows for a transgression of some confining aspects of the social experience of its participants may at the same time also potentially reinforce other parts of the social formation in ways that may not serve the interest of the people involved” (94). Kahn-Harris (2007) agrees, citing Foucault: transgression “sets ‘limits’ even as it challenges others” (30).

All three core concepts imbricate, with transgression and materiality having relational properties for example, and each functions as an interconnected domain of play’s manifestations within musicking.

Play, Higher Music Education, Genre and Performance

There is growing interest in play in higher education (HE),[6] and James and Nerantzi (2019) demonstrate the strength of awareness within the sector of the power and roles of play, which are often framed around the affective benefits of fun for learning (Wheeler and Palmer 2019), and the roles of ideation for moving beyond current frameworks of knowledge and in preparing students for an uncertain world. Engaging in play is also praised for its role in well-being within performative neo-liberal HE cultures that too often marginalize spaces for experimentation and failure (Nørgård, Toft-Nielsen, and Whitton 2017). However, Fisher and Gaydon (2019) argue that the rules and patterns of pedagogic spaces are themselves forms of play that are open to challenge: these are socially, morally and politically constructed temporal edifices. Beyond the superficial arguments of play needing to be fun or goal directed in HE, we argue that play and HE learning are aligned: that as play pushes at the barriers of structural impositions it reimagines the boundaries of both curricula and pedagogies, it frustrates and demands changed perspectives. Higher education is therefore a natural home of play.

This is not a call to play as a freedom “from” rules or structure—indeed children’s play is often saturated with the creation and renegotiation of rules—and neither is it just a call to be “playful”—the adjective here carries too little weight for an ontological claim. Rather, we echo Kanellopoulos’ (2021) concept of “studious play” as a pedagogy that “approaches education as a culture-making enterprise and not merely as a culture transmission process” (92). Whilst culture as a whole has been presented above as a crystallisation of the play force, it is play’s many forms in musicking, as exhibited in different genres, that concern us in this article.

Genre has been argued as a relational and emergent “cutting” of music’s multifarious presences (Brackett 2016) that opposes its traditional characterisation as fixed and segregated practices (Haynes 2014). Similarly, Coggins (2016) suggests viewing genre as a “constellation” (292) of reference points, a framework which upholds listeners’ subjective responses and mediates the relevance of the power structures which influence genre boundaries. Whilst we are looking at three relatively definable and well-known genres—Western art music (WAM), heavy metal, and jazz—we borrow from Huizinga (1949/2016) in arguing that all genres emerge as cultural play interacts with different personal, social, political, and environmental conditions. Given that these conditioning factors are themselves the results of play’s activities in human and non-human materials over time, we claim that choices with and within genre practices are made as play, and that sonic referencing of and within genre practices is a rich and vibrant form of musical meaning-making. Indeed, this aligns with Ellefsen’s (2022) concept of “genring” that “operationalizes existing social positions, relations, and identities” (57). It therefore seems likely that as individuals are drawn into genre affiliations, they make choices about identity formation and cultural positioning as acts of play, choices that fractally re-present themselves at different scales (Marks-Tarlow 2010) through the multiplicity of options for referencing within and between genre practices in music. Given the fluidity and performativity of genre, we choose the term “genre practices” to indicate the temporal and positional specificity of any act of genre assignment.

We use elements of performance practices within three genre practices as exemplars of how musicking-as-play manifests in different domains and registers. Given our focus on higher music education performance studies, we have examined three presentational forms; it is possible that participatory forms would offer different results.

Heavy metal: heavy metal is presented here as an example that helps to show how genre is constituted through acts of play. Without the use of insider knowledge and jokes, for example, the delineation between heavy metal and other genre practices would be far more permeable. There are also forms of play in heavy metal that are less overt, but just as important in strengthening the genre’s coherence. The fact that such a supposedly serious genre is subject to parody from within the practice itself demonstrates how play deeply underpins genre distinctions as a whole. Rooted in culturally transgressive materiality, we here seek to understand this genre through its presentation as cultural play.

Western art music: given the dominance of the conservatory in higher music education we looked for an example that offered weight in terms of the discourses and priorities of staff and students within such institutions. We settled on a soloist focus; if such a traditional “peak” instance in WAM can exhibit an ontology of musicking-as-play, then the conception is likely both useful in as conservative a sector as the conservatoire and sufficiently robust to inform significantly divergent genre practices. Looking at one exemplar event, Pekka Kuusisto’s appearance at the 2016 BBC Proms,[7] notable as much for its participatory folk-inspired encore as for its performance of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, permits insights into the thinking, values, and motivations of one leading soloist. The encore demonstrates relational, transgressive, and manifestly playful behaviour, offering material external traces of concepts also embedded, albeit much more subtly, in the concerto performance itself.

One of the difficulties in writing about WAM performance practices is that elite industry frameworks limit the permitted level of variation from the norm, as exemplified by the harsh critique of those who stray too far from the expectations of the various gatekeepers (Leech-Wilkinson 2023). There is a double play here, meaning that performers both have to “play the work” and “play within the work” simultaneously; they achieve the latter through multiple variations of non-notated elements recognizable principally to those already with strong internal models as to how they believe any particular piece “should” sound. Importantly, within WAM’s strict conventions there exist in the concerto performance micro-exemplars of musicking-as-play that this soloist then reproduces in much more visible forms during the encore.

Jazz: we argue that musicking-as-play is amplified as a play mechanism featured prominently in jazz, using here the example of the material co-authoring of enactments of silence by the iconic jazz musician Miles Davis. We specifically look at the presence of play in the performance practices of jazz as sounded and embodied in the transformative and consummatory experience of encounters and intra-actions between sound and silence. An initial study (Burnard et al. 2021) explored the multi-dimensional nature of musical silence, drawing attention to the role that silence plays in establishing an authorial voice. What was missing in this research, and what interests us in this re-reading, is to understand how the relationality between silence and sound is enacted and enhanced by the “performative transgression” of musicking-as-play as a performance practice of jazz.

II. An Assemblage of “Musicking-as-Play” Manifestations in Genre Practices

In this section we explore discourses and manifestations of musicking-as-play—that is, the underpinning of play within three genre practices through the entangled lenses of materiality, relationality, and transgression. Individual cases can and do have enormous power in terms of informing practice, asking how, why, and under what conditions performance practices and their peripheral behaviors support play to flourish. Having selected three genres with which we have individual research experience, we draw on examples that establish and constantly reconfigure the “assemblage” of concepts that have ontological significance in the capacity to trace musicking-as-play. The term “assemblage,” from Deleuze and Guattari (1987), is a constellation of singularities, made up of a myriad of elements. This term redistributes the capacity to act from an individual to a socio-material network of people, things, and narratives. Our writing will examine musicking-as-play through these genre practices and the three key imbricating concepts of materiality, relationality and transgressionality. We invite different sets of questions and alternative ways of “seeing,” “knowing,” and “doing” of both education and research (Burnard et al. 2022).

(1) Materiality of “musicking-as-play”

Heavy metal. Materiality in heavy metal musicking-as-play is connected to both its transgressive sonic materials and its consistent use of costume and merchandise for allegiance. A primal “playing” in heavy metal occurs through the essential element of distortion (Mynett 2016), which disrupts the clarity of the sine wave. The creation of a “dirty” tone can be linked to symbolic notions of impurity (Douglas 2002), which implies the potential for a playful messiness. Similarly, the common usage of dissonant intervals, such as the flattened 2nd and the tritone (Berger 1999), can also be understood as accentuated material play-acts which challenge harmonic normalcy (Shadrack 2021). At concerts, fans’ bodies are visibly involved in play-acts, with the key example being the mosh pit (cf. Riches 2011), but also in “throwing the horns,” fist-pumping, and “windmilling” one’s long hair—many of which are demonstrated and encouraged within musicians’ performances. Heavy metal fandom also engages in material play through its relationship with merchandise; fans play a transgressive “game” by wearing shocking, lurid, or grotesque designs, such as Cradle of Filth’s “Jesus is a Cunt” t-shirt. In recent years the expanding range of merchandise items and a growing number of novelty or comedy bands has led to further examples of material play, some of which is reflexive, such as Raised By Owls’ “Jesus Probably Isn’t That Bad” t-shirt.

Western art music. WAM is authored by Kuusisto when he partly achieves “double play” through a greater than normal bandwidth for timbral variety by manipulating the materials available to him in innovative ways, such as starting the second movement with a folk-inspired tone colour, using novel rhythmic stress patterns, pushing various timbral extremes—including an exaggerated portamento on occasion—and manipulating sounds away from the conventionally beautiful. This is a play with and within materials, but there appears to be a metaplay of materials themselves: Kuusisto occasionally strips the virtuosic sections of their showmanship, downplaying their presence in order to bring other, more structural and simpler melodic elements to the fore, revealing a counter-cultural interpretation that seems to play with the materiality of “the soloist” role.

Such micro-variations are not always obvious, but this is nonetheless an agentic form of play with consistent interpretative material micro-variations, in line with Chaffin, Lemieux, and Chen’s (2007) exploration of highly polished repeat performances, and Reason and Lindelof’s (2017) claims for “liveness” as a space with a play-resonance between prepared and “in-the-moment” narratives. For the encore, Kuusisto transitions from the presentational to the participatory (Turino 2008), evidencing that for him the one is playfully nested within the other, despite the dominant hierarchical narratives of the physical concert environment. Thus, within the encore emerges a material play of physical engagement between the stage, and an audience occupying simultaneous participant and observer roles (playing with the material locations of agents), sound from stage and from hall (playing with the sonic design of the concert hall), and sonic material precision with blurred audience contributions (playing with the material expectations of a WAM soundscape). This occurs alongside the play of language, meaning, and form, discussed below as transgressive elements of the encore.

Jazz. Jazz involves many possible fields of musicking-as-play. Silences can mark the beginning and the end of musical phrases, disrupt and enhance the musical flow, and be tangible presences. Jazz musicians have an acute, and often intuitive, awareness of this sound-silence relationship, and there is evidence from music psychology that, for listeners of music, musical notes are perceived in their relation to the silences that shape them (Margulis 2007). Yet in the intra-action between the materiality of sound, performers, and audiences, silence is a play act, a play force and a material which has both social and musical significance. Jazz musicians feature silence as a play mechanism. They use silence to great effect, sometimes creating a distinct authorial voice making audible the embodiment of play as sounding oneself, a form of self-crafting (Henricks 2015, 221; Sutton-Smith 1997, 92), of material authoring.

(2) Relationality of “musicking-as-play”

Heavy metal. In heavy metal, the delicate balance between musical form and content indicates that metal’s transgressions are necessarily relational, relying on the listener’s preconceptions of the musicking in order to be shocking or unusual. However, play-acts in metal culture are intentionally not always evident to the observer. Metal fans are keen to establish their differentiation from normative cultures (Allett 2013), which is most obviously achieved through “scandalous transgression” (Walser 1993, 162), but also a sense of obscurity or inaccessibility to non-fans (Kahn-Harris 2007, Phillipov 2012). This obscurity is cohered in part through the creation of playful shibboleths, or colloquially, in-jokes (cf. Coggins 2018). In heavy metal, playfulness is ambiguously paired with a grim seriousness that keeps the majority of play-acts known to fans only; this helps to produce “a subcultural community that provide[s] belonging, identity and play” (Olson 2017).

For example, the video for The Black Satans’ “The Satan of Hell”[8] relies primarily on the viewer’s awareness of the aesthetic and performative tropes of 1990s Norwegian black metal for its satirical impact, although there are some more obvious moments of play (such as musicians in corpse paint throwing snowballs at each other). A viewer who lacks the relevant knowledge might easily be confused by the low sound quality (Hagen 2011) and strange poses adopted by the musicians, but a black metal fan would be able to recognize these signifiers and, further, discern them as comedic from an “authentic” performance. The video highlights the play relationality of music genre practices: The Black Satans’ obscure parody of a seemingly serious genre is itself a means to uphold the specific codes and boundaries of black metal, as it still “worships” metal’s history (Goldhammer 2017).

Western art music. As for relationality in WAM, Kuusisto’s concerto interpretation effervesces with relational play. This is observed on an inter-human level through regular eye-contact with conductor, audience, and fellow musicians as well as through the sonic collaborations on the stage; it can also be observed on a performer-script level (Cook 2013) or with the “musically-created other” (Watt and Ash 1998; Leech-Wilkinson 2010) through interpretative choices, embodied movement, and facial gestures connected to the musicking’s ebb and flow. Relationality also appears in the laughter shared with the audience at the unexpected applause after the first movement, as the expected norms of WAM performance for silence between movements interact with the event’s unpredictable unfurling in time. Bial (2004) argues that in performance “play is understood as the force of uncertainty which counterbalances the structure provided by ritual” (115). A central element of relationality here is the resonance between the unrolling live interpretation, the notation, and the historic interpretive laminations laid down by generations of recordings, landmark performances, and teachers’ pedagogical insistences of this most famous concerto. Through these are generated individual understandings of the score, each musicker uniquely intra-acting with the previously known and the present performative. Clearly the encore marks a significant shift in the relational as the event turns toward the participatory inclusion of audience in the musicking.

Jazz. For relationality in jazz, silence might be construed as a play on the relationships between the artist, their fellow musicians, and their audiences. There are strong expectations of sound to be made, and the use of silence expresses inhibition of or disattendance to those expectations—which paradoxically, through play strengthens the relationships.

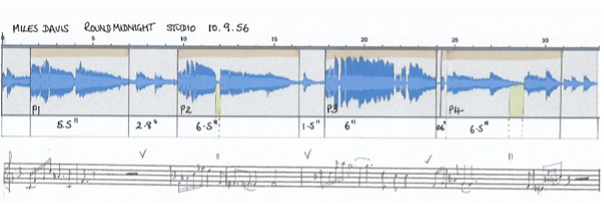

Play soundings can be heard (and seen) when analysis of silence is applied as a porous sensorium of play in the first eight bars of Miles Davis’ signature tune “Round Midnight.” We have included a visual representation of the audio waveforms and hand-drawn transcriptions because, as re-readings of the musical material, they trace silences as play, where the transformative and consummatory elements of sound and silence constitute a play field of performance. The first example, from the Sept 1956 studio recording,[9] demonstrates relatively concise sequences of interweaving sounds and silences.

Figure 1. Transcription and Audacity file of “Round Midnight” studio recording, 10 September 1956, showing “time-images” at play.

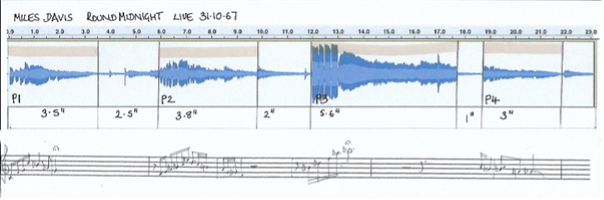

A further example comes from the 31 October 1967 live recording in Stockholm.[10] By the time Davis came to give these concerts the personnel in his band had changed, as had some of the ways in which he made audible the material authoring and enactments of his own performance creativity (Burnard and Sorenson 2023). In addition to the relational play of temporal expansion and contraction, the interplay of silence and sound takes place in the sonic in-between, in which play enactments of silence foreground the play experience.

Figure 2. Transcription and Audacity file of “Round Midnight” live recording, 31 October 1967 showing “time-images” at play.

In this example of “Round Midnight,” Davis seemed to intentionally not only “play” the theme out of tempo, but to “play” it very freely, interacting with audience expectations of this well-known standard. He is accompanied only by pianist Herbie Hancock, whose subtle and remarkable improvisations both filled and respected the spaces, or silences, between the phrases through moving together and apart in intra-action. The relationality between these two artists is particularly notable in the extended period during which Hancock drops out shortly after the quoted extract, leaving Davis alone with a silent backdrop as he plays through and with the shapes of the theme. The temporal flow was as a co-constituted movement of shifting possibilities “at play,” and patterns and intra-actions of the sound–silence nexus were reordered through the actualisation of silence itself: a relational enactment of play.

(3) Transgressionality of “musicking-as-play”

Three areas stand out as exemplars of play’s transgressional affordances in music that cut across genre practices. The first is the role of festivals in offering alternate models of social and communal relationships. Halnon (2006), for example, shows how heavy metal festivals raise “the transgression ante to the extreme” (34) and allow musicians to celebrate “the marginalized and the stigmatized” (39), at most engaging “a temporary clarification of the divided self” through disinhibited enjoyment and moral abandon (43). This transgressive behaviour acts as temporary cathartic “carnivals” of communal transgressive play necessarily enframed by a return to normalcy (Halnon 2006). Webster and McKay (2015) likewise argue that jazz festivals are transformative experiences for people, places, and musicking itself in that they permit the safe transgression of previously maintained boundaries.

Secondly, transgressionality manifests through the role of musicking in rebellion and social change. For example, one can argue that jazz is historically transgressive of both musical and social rules, absorbing multiple musical influences into a distinct practice. It featured improvisation over structure, performer over composer, and Black American experience over conventional white sensibilities, transgressing at the same time the material sound of instruments previously associated with the military. Moreover, heavy metal’s discourse has focused consistently on a “radical toleration” (Berger 1999, 282) of ideological expression, and it exists both in dialogue with and as a visceral alternative to the protest song movement. Whilst WAM has a historic connection of patronage to hegemonic authorities of church and state, that has not stopped numerous composers and performers from using their creative outputs as social commentary and as models of alternative social structures. Thus, rather than tackling injustice “head-on,” the use of musicking’s play-based transgressional capabilities acts as a play response, able to circumvent fixed obstacles in its capacity to engage human co-responses.

Finally, we argue that musicking offers transgressionality in relation to fixed models such as recordings and scores. Within WAM, manifested through the dominant presence of notation, the dangers of transgression have been carefully documented by Leech-Wilkinson (2023), who describes the infrastructure of grade exams, conservatoires, competitions, agents, and critics as “a police state” (ch. 3). This severely punishes performance beyond the normative, whilst simultaneously never quite revealing where the boundaries lie. However, the performative turn (Cook 2013) has revealed that the very act of turning notation into sound is in itself a transgressive act in relation to musicology’s historic weight on “scores” rather than “scripts.” Any sound is thus an invitation to critique according to varied criteria, which retain opacity in the service of maintaining power relations, revealing the contradicting demands of simultaneous “correct” and “unique” interpretations (Green 2011, 22). Schuiling (2019), in his contemporary study of the material relationships brought into being through notation, argues that “playing a score is not simply an exercise of agency, it is also a transformation and experimentation of agency” (454), leading to the view that celebrating the transgressive in musicking-as-play is a necessary foundation for agentic behaviours in WAM. In jazz performance, there are models set up through recordings and iconic performances that are continually referenced and transgressed; the live collaborative nature of jazz necessitates a constantly emergent epistemology through which musickers become differently, together through play.

Heavy metal. For transgressionality in heavy metal, we have already seen how sonic play conducts transgressional distortions of musical materials, although importantly, metal musicking avoids total transgression (i.e. chaotic noise) for the most part, situating elements such as extreme distortion and chromaticism within recognisable song structures and riff patterns, even in the most technically-focused subgenres (Smialek 2016). Thematic elements of darkness and chaos (Weinstein 2000) promote a strong focus on play-based transgression in the culture (Kahn-Harris 2007). Kahn-Harris (2007) introduces the term “reflexive anti-reflexivity” to explain a transgressive and performative discourse that occurs throughout extreme metal scenes, which he explains as “knowing better but deciding not to know” (145). This allows scene members to “back away” from their own objectionable statements and maintain a sense of “radical toleration” of worldviews and opinions (Berger 1999), forming a major component of heavy metal ideology, often represented discursively as “inclusivity” (Hill 2018). A key example of this is found in death metal lyrics, which often depict extreme violence against women, but nevertheless are not considered to be indicative of actual violent behaviour or bigoted beliefs amongst metalheads, even when concertgoers “ironically” perform those behaviours (Overell 2014). Phillipov (2012) suggests that death metal is akin to gory horror films, both of which encourage enjoyment “at an emotional remove, not taken too seriously;” for her, “this potentially indicates a textual basis for scene members’ practices of reflexive anti-reflexivity” (90).

Another example of this can be seen in particular bands’ use of historic milieux; Spracklen (2017) critically examines how Iron Maiden, one of the largest bands in the world with a huge international following, adopted British imperial signifiers into their live performances: “The band’s lawyers and PR managers presumably see such (British) Union flag-waving and military imagery as playful and inclusive, a piece of theatre, a piece of show-business stagecraft designed to make everyone feel a part of heavy metal enough to buy the band’s merchandizing products on the way out” (414). Reflexive anti-reflexivity is then a functional form of play, one that is (necessarily) never named as such by metalheads, and one that allows all manner of inauthentic and inconsistent behaviour to occur within a culture that places high value in appearing authentic. This is perhaps the most unique form of playfulness in heavy metal, compared to other musical cultures; no other genre relies so heavily on contradiction and ambiguity in order to sustain itself. It is also perhaps one of the most performative forms of musicking-as-play, in that it demands a constant role-playing on the part of heavy metal subcultural participants, albeit one that is profoundly un-knowing.

Western art music. As already noted, transgressionality in WAM plays out in the act of turning notation into sound. This is inherently a transgressive event, a wresting of control from the composer/publisher “materiality” of ink on paper; the soloist in our example plays the role of the fool or jester, the trickster “so frivolous he can invert frivolity” (Sutton-Smith 1997, 211) by presenting something simultaneously so profound and yet immediately lost in the momentary temporality of liveness. As it is, the BBC commentator is clearly taken with the immediacy of Kuusisto’s concerto performance, stating that he was “determined to give the impression that he was almost improvising, as if he were some folk musician … just making up the work as he went.” This implies that there is something about Kuusisto’s directness, the harnessing of the play in performance—the retrieval of the oral-aural from the literate notation (Ong 1982)—that inspires, offering a live performative transgression with “a kind of uniqueness that allows us to say ‘I was there’” (Rebelo 2006, 33). Thus, the interpretative micro-transgressions already identified of identity, materials, relationships, etc. in the musicking all add up to a unified conceptual presentation of play performed that offers those working in WAM education tools for widening the discourse on pedagogies of interpretation.

The most explicitly transgressive element of the event is the encore, which appears to break multiple conventions: the destruction of the fourth wall, the soloist singing, the foot stamping, the audience participation, the demand to sing unintelligibly in Finnish, and the crude humour of the song. Kuusisto thus sheds light on the concert format itself, externalising the play that is apparent as an internal momentum throughout the Tchaikovsky, playing both within and with the event’s framework. This is a sophisticated example of Sutton-Smith’s (1997) “meta-play”: playing “with normal expectations of play itself” (147). Kuusisto is transgressing his “role” as soloist, displaying improvisation, audience engagement, and folk music as part of his repertoire, activities which inform the debate within the conservatoire about the curriculum and its traditional narrow focus.

Jazz. In one sense the “Round Midnight” melody in the 1967 performance is transgressed as an “entity” and is dissolved into shifting clusters of shapes and contours. We are invited to think with, rather than about, the material encounter of silence, the pause, and the power of play enacted in musicking. The “infinite multiplicity” (Deleuze and Guattari 1987/2013, 296) of silence and entangled relationalities that do not appear to be proximate in space and time offers a transgressive re-working or “un/doing” of the past (the original version of the tune). The queering of the stability of spacetime coordinates and conceptual openness presumes a spatial scale in which every sounding and silencing moment “in” time is “an infinite multiplicity … broken apart in different directions” (Barad 2014, 169).

Later recordings on the same 1967 tour suggest that every night the performance was different. Maybe Davis, in each re-working, exemplified a diffractive reading of ideas played through each other, leading to more generative inventive provocations. Yet, it also disrupts what it means to be a musician (or an ensemble) in collaboration with audiences, with memories moving together and played out “in” space and “through” time. Thus, in Davis’ musicking temporal flow is transgressed as an act of play, serving as a reminder that the past, present, and future are always threaded through one another. Such diffractive use of silence is what Taylor (2016) coins “thinkings-in-the-act,” which “set practice in motion, so that practice becomes interference, always diffractive, multiple, uneasy and intense” (19).

Summary

By looking across three genre exemplars in different scales, from moment-by-moment analysis to their underpinning belief structures, certain claims can be made for a new ontology of musicking-as-play. The specific examples construct an assemblage that offers the educator potentials for thinking differently about musical practices. Borrowing from Huizinga (1949/2016, 9), we argue that genres emerge through cultural play as temporal “play crystallisations,” and that genre play is rooted not just in live musical acts but also, echoing Small (1998), in the multiple behaviours that demonstrate genre allegiance. Materiality matters in musicking-as-play as it takes forms in sonic and object presentations that resonate with genre identities. Musicking-as-play is relational in both its connectedness and its play with connections; it is always play with. Musicking-as-play has transgression as one of its life-giving systems, it is entangled with transgressive meanings and social situations.

III. Why “Musicking-as-Play” Matters in Higher Music Education

We now need to ask why play matters in higher music education, and what the implications of a speculative ontology of musicking-as-play are: how is play working in educative and performance practices and who is it working for? Play connects with discourses of power and agency in the classroom, and it has a fragility within frameworks of control. Ruddock (2017), for example, argues that “performance turns into performativity when human ‘play’ turns into a critically judged ‘thing’” (49). Kanellopoulos (2021), using the concept of “studious play,” articulates instead a vision of a music education “that celebrates ‘making ever new beginnings’ and ‘playing with and through the rules’” (81); for him, play sidesteps the hierarchies and fragilities of power structures in music education and promotes democratic classrooms.

In this article, we developed the concept of “musicking-as-play” as an ever-present underpinning of performance practices and associated peripheral behaviors in and across three music genres. The healthy nature of this force is not always a given, and at times it may be weak, stagnant, hidden or imprisoned; it certainly feels so in some education settings. Perhaps elsewhere it is a destructive force that overwhelms the capacity of the educational context to hold it; a number of writers on play warn of its destructive potential (e.g., Caillois 1961; Henricks 2006; Sutton-Smith 1997). We note Bohlmann’s (1999) word of caution regarding ontological enquiry: “‘Rethinking music’ proceeds only nervously, lacking conviction that any ontological process is ultimately knowable” (34), and so we restate the speculative nature of our work.

Whilst play is one ontology of many in music it is an ontology that clearly has significance in relation to rigid and oppressive pedagogies. We posit that the concept of musicking-as-play invites constant re-examination of educative practices, returning again to fundamentals in alignment with van der Schyff’s (2015) “ontological pedagogy … that involves reawakening to the primordial nature of human being-in-the-world” (82); this is Huizinga’s Homo Ludens, man(kind) the player. However, Reason and Lindelof (2017, 8) advocate productively moving the conversation on from ontologies, given their risk of essentialising concepts, and toward phenomenology: how does it feel to be musicking-as-play, and how, in response, can teachers devise pedagogies for higher music education that recognize, value, and nurture the play force? It is to this question that we now turn.

Reconsidering “Musicking-as-Play” in Higher Music Education’s Genre Performance Practices

We have already introduced the concept (adapted from Huizinga) of genre as a temporal “crystallisation” of the play force in music. The complexity of musicking-as-play described in this article provides a tool to reframe and disempower traditional genre hierarchies, thus freeing educators to engage in a more explorative, socially-connected, creative, and student-centred musicking, within, without, and with conventional genre frameworks. Powell (2021) reaches similar conclusions in his unravelling of competition cultures in music education, quoting Marcuse to extol “the freedom to play” (37). For Kanellopoulos (2021), learning within genre must be more than just “imposed repetition resulting from induction into musical traditions” (81), but must balance tradition and play possibilities. The discourse of play permits not just the narratives of genre hierarchies in higher music education to be sidestepped, but also such narratives of tradition and value to be understood as forms of cultural play in themselves. Whilst we sought preliminary examples from just three performance traditions, future researchers might unpick the characteristics of musicking-as-play within more diverse genres and in participatory and digital settings in higher music education.

Reconsidering “Musicking-as-Play’s” Materiality in Higher Music Education

An ontology of musicking-as-play places an awareness of the importance of material considerations at the centre of classroom practices. The centrality of play can no longer be dismissed in higher music education classroom settings with respect to sound, materiality, and the blurring of the binary of body and mind. Teachers need to invite discussions about musical instruments, musical bodies, equipment and spaces and the thing-power they possess in moments of encounter and performative engagement. These materials enact play forces and empower exploration of the generative possibilities of performance practices, compositional practices, listening practices and more. Play inhabits the body-intention nexus in music performance (Rosen 2020, 245), fuelling the resonance between internal musical models and intentions on the one hand, and fluid technical-material (re)actions and sounds on the other. Thus, bodies are authors and hosts of musicking-as-play, meaning that teachers and students need to step aside from the higher music education culture of bodies as devalued tools of sound production.

When thinking about developing and refining the material cultures of higher music education settings there are questions that need to be asked: What immanent play forces, play things, or play gestures are conventionally assigned to different music genres? What emerges through the ontological lens of play in how musicking materialises its social, philosophical, genre-specific historical situatedness? How does the force of play flourish in teaching studios as a driver of collaborative and interactive musicking through the complexity of musical materials and their exploration? How can the materiality of notation make playing a score into an exercise of agency rather than reproduction? (Schuiling 2019).

We believe that higher music education performance studies should be empowered to articulate material tracings of play in bodies and their relationships with sounding objects and the physical world, exploring the human condition through musicking-as-material-play with sounds and with selves. Rather than seeking a generic or universal performance model, for example, can there be restored in play the temporal specificity of these instruments, this acoustic, these bodies and a rejection of the imposition of this interpretation, this styling, this sound quality?

Reconsidering “Musicking-as-Play’s” Relationality in Higher Music Education

Relationality opens teachers and students to musicking-as-play as an ever-present encounter with the other, through the connectivities that sounds offer between individuals, communities, and the non-human world. Indeed, musicking in an emergent ontology of play becomes the performance of relationships (Small 1998, Camlin 2021) in both a representative and generative manner. In higher music education performance studies this empowers the socialization that both drives the educative process and serves as one of its purposes (Biesta 2009). The freedom for musicking-as-play within and with genres strengthens peer-peer relationships, student-teacher relationships, and learner-other relationships, including with schools, school communities, and those communities represented by specific genre practices. This acts as a defence against musicking’s potential to be complicit in oppression (Hess 2020). Learners need to understand such possibilities, and to recognize the role of musicking-as-play in facilitating a human-centred musicking rich in empathy and co-presence.

Through musicking-as-play in higher music education, teachers and students generate the rich fibrous connections between individuals in formation of a community of learners. However, this is no homogenizing purpose; through genre play in particular teachers and students can overcome the “othering” of those whose musical and cultural backgrounds differ from their own. This is Bradley’s (2021) “we-mode” of thinking in music in action: “so that, as individuals, we gain access to more knowledge and better understanding of those with whom we interact, including their identities, their cultural knowledge, and the backgrounds that influence their thoughts and actions” (10).

Reconsidering “Musicking-as-play’s” Transgressionality in Higher Music Education

Rules are set, policed, and regularly broken in music genre practices. Rules can be transgressed, even bypassed through enactments of play. For Allsup (2016) the music classroom as laboratory is “serious and playful, directed and free moving; it is concerned with norms and standards but always reaching beyond” (88). Our discussion of music genres has repeatedly demonstrated the central importance of various kinds of transgression to musicking-as-play, and the lack of fixed and obvious meaning to any particular musical play-act allows for transgression to thrive without reprimand. The register on which a transgressive play-act may occur (e.g., material, social, or performative) depends on the rule-system and discourses of the particular genre at hand, and transgression is latent in any relational system of agents, instruments, and rules. This connects with systems of power and prejudice in music education, exemplified by Green’s (1997) work on gender and composing; boys who transgress get praised as “creative,” girls who transgress get treated as if they didn’t understand the rules. So, there are critical justice implications to transgression in the music education classroom, not least in relation to the imposition of externalised and objectivist constructions of knowledge. As Leech-Wilkinson (2023) argues, for WAM to change from its “police state” teachers and students may all need to behave badly (ch 20.2); a mass transgressive uprising in sonic form that shows both knowledge of and a refusal to accept unethical impositions.

However, not all play is good play, and the dangers of a play ethic that disrupts moral engagement necessitates attention. Whilst an ontology of musicking-as-play draws on a critical pedagogy framework in its engagement with democratizing educational power structures (Burnard, Colucci-Gray, and Cooke 2022), it might also permit “a kind of public dialectic in which people tr[y] to advance their own personal, social and cultural positions” (Henricks 2006, 19). As such, musical transgression is entangled with relationality, and the two forces counterbalance each other. The relationality of musicking implies a respect for the play rules of others. After all, any game breaks down if the rules are not respected; and whilst all musicking is a form of play, the specific game needs agreement by its players. Play is valued “only when the participants declare it to be so” (Henricks 2015, 28). The transgressive character of play is nuanced; it is not an individual’s transgression of ensemble performance practices that marks out good play, but rather the sonic whole’s transgressions within the entangled relationships between sounds, societies, and cultures. Allsup (2016) elaborates on this: an artist who “plays disrespectfully with idiomatic material … is neither defendable nor a model for ethical music study” (108). Play’s role in reinforcing social norms is often exemplified in music education, but it can act, Janus-faced, in simultaneously setting and breaking rules, offering new explorational directions whilst also interacting with hegemonic norms.

The consequences of this understanding of “transgressive play” for higher music education are profound, and the music department should be a safe place for sonic transgressive exploration. It should be noted that teachers cannot actively encourage learners to develop transgressive musical play-acts, because this collapses the system of rules and authority necessary for transgression to occur in the first place. Transgression illustrates that musicking is not owned by, licensed by, or undertaken with the permission of teachers but rather as a manifestation of play it is a vibrant, messy, dynamic, and co-constituted sonic space, in which meaning occurs in relation to rules as well as by following them.

Concluding (Re-)Orientations: An Ethical Invitation

In summary, we introduced “musicking-as-play” as a new ontology which resets the interrelationship of materiality, relationality, and transgressionality as play domains that are fundamental and present within acts of “musicking.” Re-affirming the multi-modality of musical meaning-making practices through play across genres permits the broadening of restrictive curricula and the embrace of music’s sonic and social artefacts as elements of music’s value in play in individually unique ways for its participants.

When the curriculum and pedagogies of higher music education performance studies are perceived as practices of induction into play within genres perceived as crystallizations of the play force, there exists the potential to reorient the frameworks of power and control that accompany their ownership. The reification of reproductive practices in music education can be questioned, and musicking-as-play reframed as a fundamentally transformative and consummatory experience. This is not to insist that all musicking is contestive; an outcome of an autotelic decision might be integration and conformity, to cede control to the common purpose as a part of relational play rather than to branch out anew.[11] Indeed, the material, relational, and transgressive are in simultaneous synchrony and tension as teachers think about ethical response-ability to musicking with students and higher music education institutions.

The significance of play to education policymakers and politicians more generally is currently understated, despite the importance of play to the many cultural industries that dominate social and consumer relations, and there needs to be developed understandings of play in music that speak to political registers. Conceptualisations of play can be refined not as a childish or unfocussed experience but rather as an agentic force underpinning all musicking. When sounds, bodies, and instruments are positioned as materials of play, and teachers and learners are positioned as agents of play in relation to each other and to social conventions, music education is reframed as a practice that recognizes the ontology, the universal reality, of musicking-as-play. Music is “played.” Instruments are “played.” Bodies (both human and otherwise) are “played.” However, when all music is understood as a crystallisation of the play force as manifested through musicking-as-play then there is mobilised a (re)thinking of more democratic and learner-centred potentials for higher music education performance studies.

About the Authors

Tim Palmer is Head of Music Education and Senior Teaching Fellow at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music & Dance, London, where he researches the role of the musician in education, and into creative teaching in higher music education. His work crosses traditional boundaries between classroom teaching, instrumental/vocal teaching and community music. Tim established and leads the MA in Music Education and Performance, and the Teaching Musician programmes at Trinity Laban. He is a regular guest lecturer at the UCL Institute of Education, and a researching professional at Cambridge University, finalising a doctorate on play in the conservatoire. He is an experienced community musician and maintains a performing career as an orchestral percussionist/timpanist, notably as a member of the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique. Tim has been widely published, and he is a peer reviewer for the British Journal of Music Education and Routledge Books.

Pamela Burnard is Professor of Arts, Creativities and Educations at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. She has published widely with 20 books and over 120 articles which advance the theory and practice of multiple creativities across education sectors including early years, primary, secondary, further and higher/further education, through to creative and cultural industries. Current funded projects include ‘Choices, Chances and Transitions around Creative Further and Higher Education’ (The Nuffield Trust), and ‘Creative Learning in Higher Education Teaching of BioEconomics’ (CL4Bio) (Erasmus). She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts (RSA), Fellow of the Chartered College of Teaching, UK and Fellow of the International Society for the Study of Creativity and Innovation (ISSCI).

David Burke is a PhD student and associate lecturer at Bath Spa University, researching heavy metal music and culture. His work incorporates media studies, musicology and cultural sociology alongside critical theory, Continental philosophy and psychoanalysis, exploring vernacular practices which concern cultural continuity. His work has been published in Metal Music Studies and the Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, and he has presented papers at the London Conference of Critical Theory and the International Society of Metal Music Studies, among others.

References

Addison, Richard. 1991. Music and play. British Journal of Music Education 8 (3): 207–17.

Alaimo, S. 2012. States of suspension: Trans-corporeality at sea. Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 19 (3): 476–93.

Alcock, Sophie. 2008. Dressing up play: Rethinking play and playfulness from socio-cultural perspectives. He Kupu 2 (2): 19–30.

Allett, Nicola. 2013. The extreme metal ‘connoisseur’. In Heavy metal: Controversies and countercultures, edited by Titus Hjelm, Keith Kahn-Harris, & Mark LeVine, 166–81. Equinox Publishing.

Allsup, Randall Everett. 2016. Remixing the classroom: Toward an open philosophy of music education. Indiana University Press.

Assis, Paulo de. 2018. Virtual works, actual things: Essays in music ontology. Leuven University Press.

Attfield, Judy. 2020. Wild things: The material culture of everyday life. 2nd ed. Bloomsbury.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1936/1984. Problems of Dostoevsky’s poetics. University of Minnesota Press.

Barad, Karen. 2014. Diffracting diffraction: Cutting together-apart. Parallax 20 (3): 168–87.

Bates, Vincent C. 2021. Music education, neoliberal social reproduction, and play. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 20 (3): 82–107. http://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Bates20_3.pdf

Bell, Elizabeth. 2008. Theories of performance. Sage.

Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Duke University Press.

Berger, Harris M. 1999. Metal, rock, and jazz: Perception and the phenomenology of musical experience. Wesleyan University Press.

Bial, Henry. 2004. The performance studies reader. Routledge

Biesta, Gert. 2009. Good education in an age of measurement: On the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability (Formerly: Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education) 21 (1): 33–46.

Boeskov, Kim. 2018. Moving beyond orthodoxy: Reconsidering notions of music and social transformation. Action , Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 17 (2): 92–117. http://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Boeskov17_2.pdf

Bohlmann, Philip V. 1999. Ontologies of music. In Rethinking music, edited by Nicholas Cook and Mark Everist, 17–43. Oxford University Press.

Bowman, Wayne D. 2004. Cognition and the body: Perspectives from music education. In Knowing bodies, moving minds. Landscapes: the arts, aesthetics, and education, Vol 3., edited by Liora Bresler, 29–50. Springer.

Brackett, David. 2016. Categorizing sound: Genre and twentieth-century popular music. University of California Press.

Bradley, Deborah. 2021. Imagining music education in the ‘we-mode.’ Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 20 (1): 1–15. http://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Bradley20_1.pdf

Braidotti, Rosi, and Maria Hlavajova. 2018. Posthuman glossary. Bloomsbury Academic.

Brown, Stuart L. 2009. Play: How it shapes the brain, opens the imagination, and invigorates the soul. Avery.

Burnard, Pamela, Laura Colucci-Gray, and Carolyn Cooke. 2022. Transdisciplinarity: Re-visioning how sciences and arts together can enact democratizing creative educational experiences. Review of Research in Education 46 (1): 166–97. https://doi-org/10.3102/0091732X221084323

Burnard, Pamela, Elizabeth Mackinlay, David Rousell, and Tatjana Dragovic. 2022. Doing rebellious research in an beyond the academy. Brill-i-Sense

Burnard, Pamela, and Nick Sorenson. 2023. Making silence matter: Rethinking performance creativity as a catalysing space for sounding oneself in music education. In The Routledge companion to creativities in music education, edited by Clint Randles and Pamela Burnard, 429–40. Routledge.

Burnard, Pamela, Nick Sorensen, Satinder Gill, and Tal-chen Rabinowitch. 2021. Identifying new parameters informing the relationship between silence and sound in diverse musical performance practices and perception. International Journal of Music Science, Technology and Art 3 (1): 7–17. https://doi.org/10.48293/IJMSTA-71

Caillois, Roger. 1961. Man, play and games. University of Illinois Press.

Camlin, Dave. 2021. Recovering our humanity – what’s love (and music) got to do with it? In Authentic connection: music, spirituality, and wellbeing, edited by June Boyce-Tillman and Karin S. Hendricks, 293–312. Peter Lang.

Chaffin, Roger, Anthony F. Lemieux, and Colleen Chen. 2007. It is different each time I play: Variability in highly prepared musical performance. Music Perception 24 (5): 455–72. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2007.24.5.455

Coggins, Owen. 2016. “Record store guy’s head explodes and the critic Is speechless!” Questions of genre in drone metal. Metal Music Studies 2 (3): 291–309.

Coggins, Owen. 2018. Mysticism, ritual, and religion in drone metal. Bloomsbury Studies in Religion and Popular Music. Bloomsbury Academic.

Cook, Nicholas. 2013. Beyond the score: Music as performance. Oxford University Press.

Cook, Nicholas. 2018. Music as creative practice. Oxford University Press.

Cross, Ian. 2009. The evolutionary nature of musical meaning. Musicae Scientiae 13 (2_suppl): 179–200.

Csepregi, Gabor. 2013. On musical performance as play. Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 46 (46): 96–114.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 1987/2013. A thousand plateaus. Translated by Brian Massumi. Bloomsbury.

Dissanayake, Ellen. 2017. Ethology, interpersonal neurobiology, and play. American Journal of Play 9 (2): 143–68.

Dodd, Julian. 2007. Works of music: An essay in ontology. Oxford University Press.

Dorschell, A. 2018. Music as play: A dialogue. In Virtual works, actual things: Essays in music ontology, edited by Paulo de Assis, 115–34. Leuven University Press.

Douglas, Mary. 2002. Purity and danger: An analysis of concept of pollution and taboo. Routledge.

Eberle, Scott G. 2014. The elements of play: toward a philosophy and a definition of play. American Journal of Play 6 (2): 214–33.

Ellefsen, Live Weider. 2022. Genre and ‘genring’ in music education. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 21 (1): 55–79. https://doi.org/10.22176/act21.1.56

Elliott, David J. 1995. Music matters: A new philosophy of music education. Oxford University Press.

Elliott, David J., ed. 2005. Praxial music education: Reflections and dialogues. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Fisher, Rebecca, and Philip Gaydon. 2019. The dark would: Higher education, play and playfulness. In The power of play in higher education, edited by Alison James and Chrissi Nerantzi, 77–92. Palgrave Macmillan.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. 1975. Truth and method. Continuum.

Goldhammer, Rio. 2017. After the apocalypse: Identity and legitimacy in the postdigital heavy metal subculture. Metal Music Studies 3 (1): 135–44.

Gray, Peter. 2013. Free to learn : Why unleashing the instinct to play will make our children happier, more self-reliant, and better students for life. Basic Books.

Green, Chelsea C. 2011. Permission to play: Obstacles and open spaces in music-making. Visions of Research in Music Education 18: 1–31.

Green, Lucy. 1997. Music, gender, education. Cambridge University Press.

Hagen, Ross. 2011. Musical style, ideology, and mythology in Norwegian black metal. In Metal rules the globe: Heavy metal music around the world, edited by Jeremy Wallach, Harris M. Berger, and Paul D. Greene, 180–99. Duke University Press.

Halnon, Karen Bettez. 2006. Heavy metal carnival and dis-alienation: The politics of grotesque realism. Symbolic Interaction 29 (1): 33–48.

Haraway, Donna. 1992. The promises of monsters: A regenerative politics for inapproprate/d others. In Cultural Studies, edited by Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson, and Paula Treichler, 295–337. Routledge.

Haynes, Jo. 2014. Music, difference and the residue of race. Reprinted. Routledge.

Henricks, Thomas S. 2006. Play reconsidered: Sociological perspectives on human expression. University of Illinois Press.

Henricks, Thomas S. 2015. Play and the human condition. 1st ed. University of Illinois Press.

Henricks, Thomas S. 2018. Theme and variation: Arranging play’s forms, functions, and ‘colors’. American Journal of Play 10 (2): 133–67.

Hess, Juliet. 2020. Finding the ‘both/and’: Balancing informal and formal music learning. International Journal of Music Education 38 (3): 441–55. https://doi-org/10.1177/0255761420917226

Hill, Rosemary Lucy. 2018. Metal and sexism. Metal Music Studies 4 (2): 265–79.

Huizinga, Johan. 1949/2016. Homo ludens: A study of the play-element in culture. Angelico Press.

Husserl, Edmund. 1970/2001. Logical investigations. Routledge.

James, Alison, and Chrissi Nerantzi. 2019. The power of play in higher education: Creativity in tertiary learning. Palgrave Macmillan.