CHRIS RICKETTS

University of Portsmouth (UK)

November 2025

Published in Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 24 (6): 59–88 [pdf]. https://doi.org/10.22176/act24.6.59

Abstract: Despite ongoing calls for student voice and culturally responsive teaching in music education, understanding, acknowledging, and implementing these ideals remain challenging due to accountability mechanisms in the education system. This paper presents a theory-informed practitioner-research study that combines practitioner reflections with composite vignettes from five teacher interviews. Drawing on Regelski’s (2016) praxial philosophy and Freire’s (1972) critical pedagogy, it introduces the PRAAX model as a framework for examining student voice and agency through critical praxis. Through reflexive accounts and the perspectives of five experienced music teachers, I demonstrate how the PRAAX approach has the potential to contribute to socially conscious and culturally relevant music learning, while revealing the tensions involved in navigating institutional constraints. The PRAAX model positions the teacher not just as a curriculum deliverer, but as a critically engaged practitioner facilitating democratic and dialogic musical spaces for students whilst offering a reflective framework for professionals.

Keywords: Critical pedagogy, student voice, praxis, practitioner reflections, informal learning, music education

Music education has always been closely linked to identity, culture, and power. Within my practice, I have often found myself negotiating between what I believe music education should be—a participatory, dialogic, and ethically grounded endeavour—and what it is frequently expected to be—a performance-driven, exam-aligned subject constrained by policy and school accountability frameworks. This tension has made me question what I teach, how I teach it, and why.

In this paper, I employ a mixed methodology that combines practitioner reflection with composite vignettes drawn from interviews with five curriculum leaders. These reflections allow for critical professional honesty and reflexivity, while the interview vignettes illustrate broader, shared challenges across school contexts. Both are framed through the theoretical perspectives of Regelski (2016) and Freire (1972), whose visions of praxis as socially situated underpin the PRAAX model.

Thomas Regelski (2016) suggested, through his praxial philosophy, that music education should be socially situated and ethically responsive, grounded in the ways music impacts students’ lives. When I refer to music education as ethically responsive, I am drawing on Regelski’s (2004, 2009) interpretation of phronesis in music teaching—not just following technique or tradition, but making context-sensitive, relational decisions that consider the well-being, needs, and lifeworlds of students. Phronesis requires ongoing reflexivity, not only about what music is taught, but why, how, and for whom. An ethically responsive practice, then, recognises teaching as a moral activity, one that resists one-size-fits-all solutions and instead prioritises pedagogical choices that serve students in their real social and musical contexts. Paulo Freire (1972) offered a pedagogy of liberation that centres voice, critical reflection, and the transformation of oppressive systems through dialogue and what he calls “conscientização” (critical consciousness). Critical consciousness provides students with a framework for understanding society, focusing on what is unequal or unjust in it. In this article, I draw on Regelski’s (2016) and Freire’s (1972) work to explore how music education can become a site of socially grounded praxis. Reflection and action merge to support justice-oriented, culturally responsive teaching.

While these frameworks offer possibilities, they raise ongoing tensions that I have encountered and identified related to my practice as a teacher of secondary school students (11–16-year-olds). Questions about what student voice and agency look like in the music classroom and how music educators can ensure it is meaningful rather than tokenistic have shaped my thinking over time. Rather than offering definitive answers, I employ reflective inquiry to explore the preconditions, risks, and complexities of enabling student agency within music education. In doing so, I consider the necessary skills and contextual factors that shape how music learning can become more equitable and dialogic. It is essential, first, to define what is meant by “student voice.” I define student voice as the capacity for students to express, shape, and influence their learning experiences in meaningful ways that are beyond surface-level consultation or tokenistic choice. Cook-Sather (2006) highlighted that student voice refers to students having the opportunity, ability, and authority to contribute to decisions about their education. In the context of music education, this could include selecting repertoire, contributing to curriculum discussions, engaging with classroom norms, or co-developing assessment criteria. Pedagogically, voice is about being heard, taken seriously, and engaged with, and not just speaking.

In this article, I reflect on my experiences and propose rethinking how music education is conceptualised and enacted, particularly within policy-bound secondary school contexts, where it remains a statutory entitlement up to age 14 in much of the world (UNESCO 2010; Bamford 2006). Using narrative inquiry and theoretical dialogue, I introduce the PRAAX model, a framework that is a work in progress designed to support an equitable, inclusive, and culturally responsive classroom. Whilst navigating this, I examine the risks and contradictions of using this model in real-world contexts.

Positioning Narrative Inquiry

Throughout the article, I invite those involved in music education or research to rethink what music education could be when attending to student voice becomes a foundation of pedagogy in which choice is scaffolded, not superficial, and through which teachers—not just as curriculum deliverers but as ethical practitioners—co-create Musical Futures and experiences with students. To explore these questions, I will use practitioner reflections as both a critical tool and a form of professional honesty and acknowledge the vulnerability that comes with sharing insights from my practice. This methodological choice is made intentionally and with purpose. For Regelski (2016), teacher practice is a site of ethical inquiry and social responsibility, and for Freire (1972), transformation begins with naming and knowing one’s reality. Practitioner reflections, in this instance, then become a method fully aligned with both theorists’ calls for education that is reflexive, situated, and grounded in lived experience. Rather than seeking objectivity or generalizability, I work within the narrative of practitioner research that foregrounds and celebrates lived realities, reflexive meaning-making, and situated knowledge (Ellis et al. 2015; Bernard and Rotjan 2021). This aligns with both Regelski’s vision of praxis as morally responsive music teaching and Freire’s notion of education as a transformative process grounded in dialogue and experience.

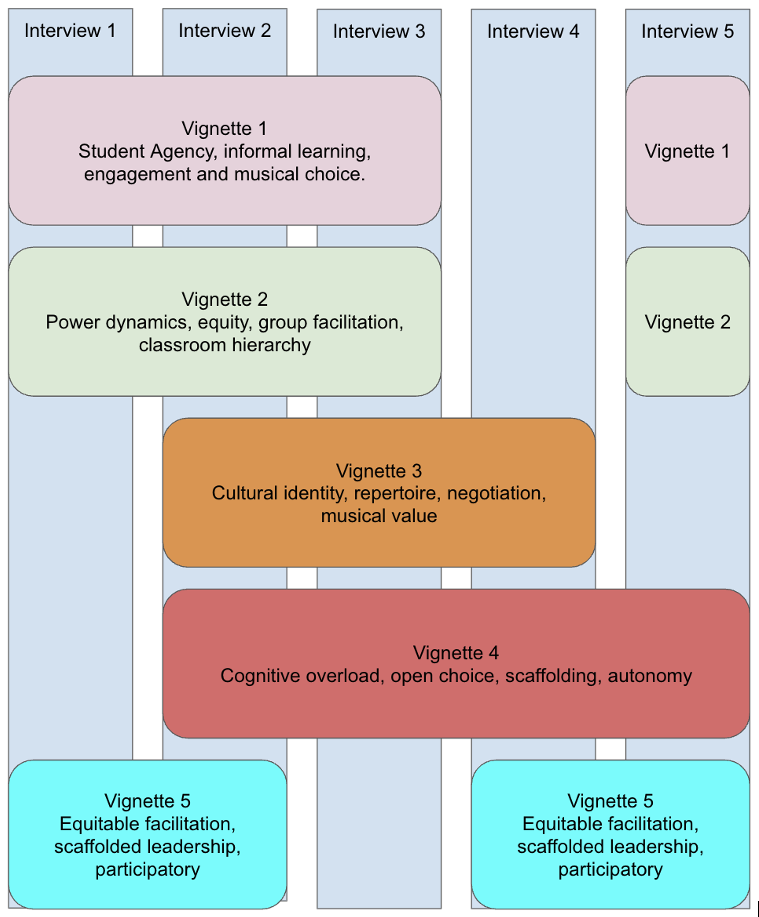

I share vignettes and insights throughout this article, drawn from diverse teaching contexts and presented not as universal claims but as stimuli for practitioner reflection. These vignettes are fictional composites of themes that have emerged from semi-structured interviews with five teachers. Fictionalisation serves both an ethical and analytical purpose, protecting identities through abstraction while enhancing narrative coherence (Ellis et al. 2011; Barone and Eisner 2012; Leavy 2020). I chose this approach due to its flexibility and ability to elicit context-specific insights while maintaining consistent themes (Kallio et al. 2016). The five teachers interviewed were curriculum leaders in music, and the interview questions were open-ended and centred on curriculum development and inclusivity. Key themes of the interview were identified through thematic analysis and validated by the participants (Braun and Clarke 2006). This was achieved by offering summaries of thematic interpretations and inviting participants to confirm the validity of the themes. Participants had an opportunity to provide feedback and offer clarification, thereby supporting the credibility and co-construction of meaning. Consent was obtained for the interviews, along with the right to withdraw at any time. These vignettes have been created to reflect shared experiences, perspectives, and tensions that are not my own, but also capture the broader concerns across music education that arose during the interviews. Figure 1 illustrates the key themes of the interviews and how each vignette connects to these identified themes.

Figure 1. Thematic Matrix Showing Vignette Links to Teacher Interviews

This study received ethical approval from the University of Portsmouth, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (reference number FHSS 2024-098). All participants provided informed consent before the interviews and confirmed the themes of the interview alongside being offered the opportunity to discuss and elaborate on the identified themes. Procedures followed the institution’s ethical guidelines for research involving human participants.

My reflections are grounded in over a decade of teaching in UK state secondary schools, with some experience in private international settings and work as a peripatetic teacher. I have worked mainly with students aged 11–16 from diverse socio-economic and cultural backgrounds. In my current role as a curriculum leader at a mixed comprehensive school, I work with classes of varying musical experience, including students with instrumental training and those who can access music only within the formal classroom setting. Music is taught one hour a week to all students aged 11–13, after which time it becomes an optional activity for those who wish to continue their musical studies. Class sizes in the lower secondary (11–13-year-olds) tend to be between 25 and 30 students per class and follow a whole-class ensemble structure, incorporating key components of the national curriculum such as performance, composition, listening skills, singing, notation, and contextual awareness of music. I also have the role of writing, overseeing, and developing curriculum for several secondary schools.

Theoretical Grounding: Praxis as Ethical and Transformative Action

Any music praxis—indeed, any social praxis, from therapy to nursing to teaching (etc.)—comes with an expectation of ethical competence on the part of the practitioner. Thus, a musical praxis must competently serve the needs of particular (socio-musical) situations (Regelski 2022, 17).

While both Regelski and Freire emphasised praxis as ethically grounded and socially situated, their interpretations reflect distinct disciplinary contexts, theoretical commitments, and goals. Regelski, writing from within the field of music education, advocated for a praxial philosophy rooted in the everyday musical lifeworlds of students. For him, music education did not revolve around abstract aesthetic ideals or technical formalism but should enable students to become musical agents who can use music meaningfully throughout their lives. Formalist music education typically emphasises aesthetic appreciation, score analysis, and performance of Western art music, often treating music as an autonomous art form rather than a social practice. Regelski (2004, 2016) critiqued these formalist approaches to music education that prioritise reproduction of canonical works, which are often detached from students’ social realities. Instead, Regelski advocated for a praxial alternative—music education that is participatory, contextually grounded, and socially responsive. Teaching music is not about preparing for performance or exams, but about students becoming musical agents in the world, able to use music meaningfully throughout their lives. Praxis, in this sense, is relational, purposeful, and enacted through real-world musical doing.

Freire located praxis within a broader socio-political struggle for emancipation. His concept of critical consciousness requires learners to examine the systems and ideologies that are in their lives and position themselves as agents of change. Freire explained that education can never be neutral; it is either an instrument of liberation or domination. An egalitarian education, as Freire argued, begins when learners and teachers engage in dialogue, posing critical questions about the world and envisioning how it might be transformed. Critical consciousness is the process through which learners become aware of injustice and begin to see themselves as capable of shaping their realities.

There are several key differences between Regelski and Freire’s viewpoints. While Regelski’s approach centres music as a form of community engagement, Freire’s pedagogy hinges on the political nature of educational encounters. These positions are far from contradictory; they are complementary to each other. Regelski explains a contextually responsive musical practice, while Freire offers a political call for reflection and action. Combined, they challenge passive, teacher transmission-based models of learning and demand that educators become reflexive practitioners. These convergences and divergences underpin the development of the PRAAX model I present later in this paper, through which I seek to synthesise Regelski’s call for musically situated learning with Freire’s vision of education as a dialogic, transformative act.

In my reflections and practice, both theorists speak to the daily tensions I navigate between policy-driven constraints and relational, justice-oriented pedagogy. The PRAAX model was developed not to resolve these tensions, but to live within them, creating space for ethical deliberation, student voice, and shared meaning-making.

To clarify how Regelski and Freire each contributed to the framing of praxis in this article, I have created Table 1 as a comparative tool. It is not directly drawn from either author but synthesises key themes across their respective works to highlight shared commitments and distinct emphases. This interpretive table is designed to support the development of the PRAAX model by identifying conceptual intersections between praxial music education and critical pedagogy.

Table 1. Regelski and Freire on Praxis

| Theme | Regelski | Freire |

| Definition of Praxis | Praxis is music education as a socially situated, ethical action. It responds to students’ lifeworlds and aims for lifelong musical engagement. (2016, 11) | Praxis is the unity of reflection and action aimed at liberation. It involves learners becoming critically conscious and transforming their world. (1970, 79) |

| View of the Teacher | The teacher is an ethical practitioner, not a technician. Teaching is a relational, responsive, and socially embedded process. (2009, 74) | The teacher is a co-learner and facilitator of dialogue. Their role is to empower, not to deposit knowledge. (1970, 80) |

| View of the Student | Students are music-makers, whose everyday musical practices hold educational value. (2004, 9) | Students are subjects of their learning, capable of naming and changing their reality through critical reflection. (1970/2000, 83) |

| Purpose of Education | To enable meaningful, functional musicianship that serves personal and community life beyond school. (2004, 7) | To awaken critical consciousness and promote freedom, agency, and transformation. (1970/2000, 81) |

| Curriculum and Content | Must be relevant to students’ musical cultures and adaptable to diverse contexts. Rejects canon-driven models. (2009, 77) | Must emerge from the lived experiences of learners. Encourages problem-posing content rather than fixed knowledge. (1970/2000, 96) |

| Dialogue and Voice | Student voice is central—music education should be participatory and negotiated. (2016, 38) | Dialogue is foundational. True education happens through listening, questioning, and shared inquiry. (1970/2000, 88) |

| Assessment and Success | Assessment should reflect musical growth, relevance, and community impact, not just formal skill. (2004, 210) | Success is measured by empowerment and the ability to act critically and ethically. (1970/2000, 66) |

Recent student surveys have confirmed that culturally relevant teaching improves engagement and equity in music education (Cumberledge and Williams 2023). Culturally relevant pedagogy, as defined by Ladson-Billings (1995), is grounded in three principles: academic success, cultural competence, and critical consciousness. In music education, this requires recognizing students’ cultural identities and affirming them. It also means helping them acquire the tools to engage critically with music and the world around them. This approach aligns with Freire’s (1970) notion whereby students develop the capacity to question and transform social conditions. It also resonates with Regelski’s (2004) call for teaching that is socially situated and ethically purposeful. What culturally relevant teaching looks like in practice continues to evolve, but it remains an essential framework for repositioning music classrooms as sites of identity, agency, and justice.

These issues are not abstract. They are reflected in lesson plans, repertoire choices, and in whose voices are heard (and those who are not) during rehearsal. They live in the tension between teacher-led goals and student-led agency, between curriculum requirements and cultural relevance or necessity. Again, in this article, there are constant balances to navigate between responsiveness in lesson planning, between repertoire and representation and between whose voices are heard or not. The intention is not to resolve them but to explore what it means to inhabit them honestly and critically as part of an ongoing commitment to praxis and equality in the music classroom.

Student Voice, Musical Choice, and the Realities of Informal Learning

Informal learning can centre students as musical agents, composers, arrangers, listeners, and leaders (Feichas 2010; Bull 2015). Rooted in Green’s (2008) seminal work and popularised through models such as Musical Futures, informal learning has been a powerful vehicle for enacting student voice and choice in music education. Musical Futures is a UK-based approach that encourages student-led ensemble work, repertoire selection, and peer collaboration, often using popular music and informal learning processes to mirror what happens in the real world (Musical Futures 2022). This approach shares similarities with the Music Will program (formerly Little Kids Rock) in the United States, which also emphasises student-led ensemble work, popular music, and access to culturally relevant instruments and resources in under-resourced schools (Music Will 2024). Both programs focus on shifting the teacher’s role to that of facilitator, giving agency to students for repertoire choices, instruments, and groupings. By using these informal approaches, elements of Music Will and Musical Futures argue that teachers have the ability to transform the classroom into a space of dialogue, collaboration, and authentic engagement. Feichas’s (2010) study showed these effects in Brazil, where combining informal and formal learning gave students ownership and creative autonomy. A question remains about the correct balance between autonomy and structure.

Vignette 1—Informal Leaning

When teachers opened the floor for students to share their musical interests in the classroom, there was a clear shift in engagement. Those who regularly sat back and did not engage were now involved in conversations around repertoire, eager to share their interests with peers. Students would then engage with discussions about their musical learning outside the classroom and were keen to book practice rooms during their breaktime. These rehearsals shifted from a place of instruction to a place of negotiation and experimentation that was student-led, making music learning less about rules and more about conversation and community.

Teachers explained how students brought in their songs, shared Spotify links, negotiated arrangements, and led ensemble rehearsals. Musical learning in this context became less about compliance with teacher instruction and more about conversation between students, which energised the learning and made it meaningful in relation to the students’ lived musical experiences. This outcome is similar to that of Law and Ho’s (2015) study in China, where students expressed frustration when their music preferences were excluded from the school curriculum. In Freirean terms, the classroom became a site of dialogue, where students’ cultural and musical preferences are not only recognised but invited into the centre of the learning process. In Regelski’s terms, the musical practices that take shape are then deeply embedded in students’ lifeworlds and recognised as legitimate.

Power Dynamics and Group Facilitation

Voice, choice, and student agency come with multiple challenges. Freire (1970) warned that freedom without structure may lead to despair or manipulation rather than liberation. Freire highlighted that “freedom is acquired by conquest, not by gift” (29). Regelski (2009, 12) also cautioned that unstructured music-making without pedagogical framing can replicate existing social hierarchies.

Vignette 2—Power Dynamics

As the group settled in the practice room, one student quickly took charge. They chose the song, allocated parts, and the group of less confident players complied. When they did make suggestions, they were not always acknowledged or listened to; it was clear that the musically experienced students were leading the group. What was meant to be collaborative in practice was being quietly controlled.

In group settings, teachers explained that dominant voices (more musically experienced students) may direct decision-making, select repertoire, assign roles, or dismiss suggestions from others. What has surfaced here are the subtler dynamics of power, confidence, and peer influence that often shape democratic participation in any form. Diversity in confidence, experience, or cultural background can lead to an uneven distribution of power. O’Flynn (2005) suggests that equality of opportunity does not facilitate an equality of voice. Without deliberate teacher facilitation and intervention, student-led ensembles may reproduce classroom hierarchies, with dominant students deciding the musical direction while others remain peripheral. Teachers must be aware of this dynamic, not to control the process, but to create conditions where all students can become confident in contributing to the learning experience. This may involve rotating leadership roles, establishing group norms, and observing routines, or encouraging students to reflect on the decisions made and whose voices were heard, as well as the reasons behind those decisions.

These tensions echo wider social hierarchies and highlight that student voice is not a neutral or equalising force; it must be actively facilitated and distributed. Hess (2020) found that student autonomy requires careful and selected scaffolding to prevent exclusion. She explains that informal learning spaces can reproduce social inequalities as discussed earlier, and confident or more dominant students can unintentionally (or intentionally) exclude peers. Similarly, Evans et al. (2015) observed peer tensions in group rehearsals during a Musical Futures pilot in Wales, reinforcing the need for the teacher to mediate and monitor student interactions.

Identity, Culture, and Repertoire

Hess (2017) suggested that peripheral multiculturalism can often mask inequities in curriculum design without addressing issues that surround representation and equity. Bradley (2006) warned that multicultural inclusion, when limited to isolated songs or celebrations, can function as a form of tokenism that reinforces and supports dominant paradigms rather than challenging them. In some cases, repertoire becomes a symbolic gesture rather than a site of genuine engagement with cultural knowledge systems or student identity. By using the praxial and dialogic lens, repertoire selection becomes part of a larger ethical conversation about whose music is valued, how it is taught, and who has the authority to make such decisions.

Vignette 3—Repertoire and Cultural Identity

One student arrived eager to perform a grime/rap track they’d been listening to, only for another to quietly suggest it “wasn’t appropriate.” Instead of shutting the conversation down, the teacher asked the group: What does “appropriate” mean? Who gets to decide this? What followed was a lively discussion about cultural assumptions, musical value, context of the music, and the purpose of performance. In the end, they chose to adapt the piece for the school stage, but the real lesson was in the dialogue that led them to this decision.

A further tension that emerged when interviewing teachers was around students’ emotional attachments to a particular repertoire. On occasion, when students have expressed wanting to learn a personal or favourite piece of music, they have been less open to critiquing or adapting it. This can harm the rehearsal processes and limit musical progress. In my reflections on practice, I have considered the need to be careful, relational, and aware of these issues, respecting students’ musical identities while protecting the space for learning, experimentation, and growth. Often, the theme of inappropriate repertoire has come up, and this has created tensions over what is fitting for a school environment. Rather than dismiss or ignore the comment, I suggest having an honest discussion: What do we mean by “appropriate,” and who gets to decide that? This could lead to a meaningful class conversation about cultural assumptions, musical value, and the purpose of the performance. This also opens opportunities for understanding the language that is used in music, its societal placement, and its meaning and connection to a particular student’s cultural identity. This ultimately shows the importance of creating space for student dialogue without treating personal repertoire and musical identity as untouchable.

While these cultural dynamics shape what students bring into the classroom, they also influence how students respond when given a choice. In the following section, I examine what happens when freedom itself becomes overwhelming and how we can support students in navigating musical decision-making with confidence and care.

Vignette 4—The Challenge of Open Choice

“We can pick anything?” asked one student, iPad at the ready with YouTube tabs open, ready to share. The room was filled with groups all playing each other snippets of songs, none of which lasted more than 10 seconds before being dismissed by a group member. Forty minutes later, and in some cases, two lessons later, no music has been played. What began as freedom had quickly turned into uncertainty, frustration and conflicts of identity.

Another challenge arises when asking students to choose material, particularly when the possibilities are open-ended. What started as freedom can quickly become paralysis; it was identified that on many occasions, students were unsure where to begin, and some groups spent an entire lesson scrolling through YouTube and discussing musical options. One of the most frequently recurring questions that teachers identified was a simple one: “Where do we start?” or “How do we do that?” For many students, particularly those without access to musical training outside of school, the world of repertoire can feel overwhelming, vast, and cognitively challenging. Their knowledge of how to access resources to support their learning can be woefully limited. Without guidance and proper facilitation from the teacher, the freedom to choose becomes a burden, rather than the liberating act that it was intended to be. Here lies a potential opportunity for teacher scaffolding and modelling to support student understanding and learning and encouraging moments for dialogue. Suggesting genre-based playlists could help students navigate the vast landscape of musical possibilities. It also enables a space for meaningful conversations between students and teachers. Questions arise at this stage to promote teacher and student reflections: Why are we drawn to certain styles? Whose music gets included? What musical skills do we, as teachers, want the students to develop?

In reflection, I am reminded that musical choice is not inherently empowering unless students have the cognitive, social, emotional, and musical tools to navigate it. Freire (1970) wrote of education as the development of critical consciousness; Regelski (2004) insisted that music education must equip students to be lifelong musical citizens. Both point to the need for thoughtful scaffolding and understanding of the skills we teach in the music classroom. However, what does that look like?

Before students can meaningfully exercise choice, we must attend to their metacognitive readiness. This includes their ability to evaluate repertoire, negotiate roles, reflect on process, and understand what makes a piece “work” musically. It also includes basic musical tools and fluency, such as reading chord charts, recognising and understanding harmonic structures, or accessing learning materials in numerous formats. Green (2008) reiterated that students thrive when informal learning is preceded by structured teacher input and functional modelling. Without these foundations, student voice becomes superficial or even exclusionary. Biddulph (2011) supports this view, arguing that curriculum agency must be structured and not accidental. Moreover, the role of a teacher is to guide students toward the kind of informed, empowered voice that lies at the heart of Freire’s and Regelski’s conceptions of praxis. A trustworthy musical agency requires preparation, reflection, and support. In the next section, I suggest the preconditions necessary for student voice and agency to be successful. These reflections illustrate the complexities of centring voice in informal learning contexts. They echo Freire’s belief that “liberating education consists in acts of cognition, not transferals of information” (Freire 1970, 79), and Regelski’s argument that meaningful music education must foster deliberate musical agency rather than passive participation (Regelski 2004, 16).

Musical Metacognition and the Preconditions for Voice

To enable meaningful agency and avoid superficial forms of student choice, teachers must understand the reflective and musical conditions that make such agency possible. Metacognition is the ability to reflect on and regulate one’s learning, foundational to independent musical engagement (Callender et al. 2016). Without it, open-ended tasks can become paralysing. Students may hesitate to begin, look to dominant peers, or default to familiar choices, which can limit their exploration and curiosity. While this can offer short-term guidance which can lead to positive musical experiences, it can also discourage independent contribution or musical development—ultimately reinforcing existing hierarchies which can challenge the equitable musical experience. Benton (2013) noted that developing metacognitive habits such as goal setting, process evaluation, and strategic planning enhances students’ capacity to direct and control their learning. In music classrooms, students’ metacognition might take the form of articulating rehearsal goals or evaluating the impact of a chosen piece of music. While such skills develop informally, in classroom contexts they are strengthened when intentionally modelled and embedded into practice, with key terminology and expressive tools introduced to support and extend students’ musical growth.

While student voice can and often does emerge organically through the music-making process, it can be deepened and made more equitable when deliberately cultivated and supported through intentional structures. Biddulph (2011) notes, curriculum agency must be structured, not accidental. Hess (2020) warned that informal learning environments can easily reproduce existing social hierarchies if not carefully mediated by the teacher. Students must participate actively in repertoire, process, or creative direction decisions; this participation requires more than opportunity and time. Autonomy, in this sense, is not granted; it must be cultivated and planned. In this section, I argue that musical metacognition is a crucial precondition for voice and agency, shaping the conditions under which students can then engage with choice in more meaningful and democratic ways.

Parallel to this cognitive readiness is the necessity of musical knowledge. When students lack the technical or conceptual grounding to realise their ideas, the agency promise becomes valueless. Here, teachers must tread carefully, as their expertise in guiding musical skills could limit and devalue students’ musical experiences. Burnard (2012) emphasised the importance of recognising multiple creativities and diverse ways of making and understanding music, which requires tailored pedagogical structures. Scaffolding in this context is not about limiting student autonomy but enabling it. Teachers could introduce genre-specific frameworks or lessons, offer simplified arrangements, or provide listening guides that encourage students to engage constructively with musical material. Scaffolding becomes a responsive act that continually adjusts to students’ ever-changing needs rather than imposing a predetermined route. The idea is that students must learn basic musical and metacognitive skills to be fully agentic in their musical learning.

Beyond individual skills, structured learning experiences are crucial in preparing students for autonomy in ensemble settings. Ng (2018) suggested the need for intensive musical learning camps where foundational ensemble skills are developed in concentrated settings to prepare students for autonomous group work. This argument highlights a broader concern in informal learning literature: freedom without the necessary metacognitive and musical skills can lead to inequity, exclusion, or stagnation (Green 2008; Jaffurs 2004; Karlsen 2010b). In student-led ensemble contexts, musical decision-making relies on confidence and the ability to communicate musically, which requires a basic understanding of music. As such, the teacher plays a pivotal role as a facilitator of musical and social learning (O’Flynn 2005; Folkestad 2006), helping students develop the confidence and skills to make personal and purposeful choices in collaborative contexts. Autonomy then becomes the outcome of structured musical learning.

Importantly, musical participation must also be scaffolded. Students often bring substantial emotional investments to the music they choose, particularly when that music is linked to their identity and memories. Karlsen (2010a) illustrated how culturally sustaining pedagogy in music can affirm students’ identities, but only when accompanied by relational and dialogic teaching. While culturally responsive pedagogy aims to acknowledge and integrate students’ cultural backgrounds into teaching, culturally sustaining pedagogy goes further by actively supporting and preserving students’ cultural practices as a means of resisting assimilation (Paris 2012; Ladson-Billings 2014). In music education, this means validating and co-creating musical knowledge with students in ways that affirm and support their identities and position them as cultural contributors. In such spaces, choice is an expressive act with personal significance. Teachers who recognise this emotional weight can support students in navigating the vulnerabilities that come with sharing, modifying, or critiquing music that matters deeply to them.

Student voice must be nurtured through critical thinking, reflective action, and intentional collaboration, built on solid musical and cognitive foundations. The teachers’ task is not to remove authority or structure entirely, but to reimagine it as facilitative: to build the foundations which allow voice to be exercised authentically, relationally, and musically. This emphasis on scaffolding and reflection aligns with the PRAAX model’s commitment to reflexivity and authentic participatory learning.

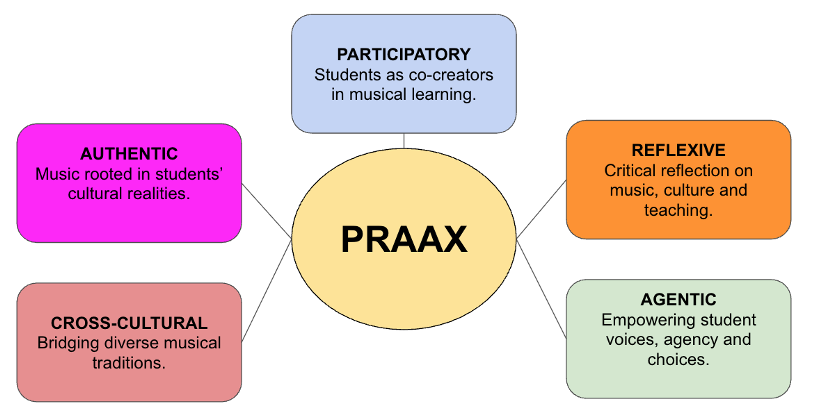

Introducing the PRAAX Model: Framework for Culturally Responsive Praxis

In my reflections on practice, sustained engagement with Regelski’s and Freire’s ideals over several years led to the development of the PRAAX model, comprising five strands: Participatory, Reflexive, Agentic, Authentic, and Cross-cultural. The concept emerged from my reflective practice and research as a framework to support culturally responsive, justice-oriented music education. Still in its early stages, PRAAX represents a working model-in-progress, shaped by iterative practice cycles, reflection, and student dialogue inspired by advocates of action research (Kemmis and McTaggart 1988). It is not presented here as a fully established theory or framework, but as a pedagogical reflection tool grounded in the praxial philosophy of Regelski (2016) and Freire’s critical pedagogy (1972).

PRAAX is not intended as a prescriptive model but as a guiding framework for educators seeking to centre student voice, relevance, and ethical action in their pedagogy. What follows is an outline of each principle, drawing from the theoretical underpinnings of Freire and Regelski.

Participatory

The first dimension of the PRAAX model emphasises active musical involvement as a foundation for equity and relevance in the classroom. Students are not passive recipients but co-creators in the musical learning process. Their cultural experiences, knowledge, and experience shape the direction of the school. Regelski’s (2004) praxial philosophy emphasizes music as a social act involving active participation. He argued that attending to how music is created, performed, and heard by specific people in specific social contexts is key to observing music’s sociality in action. This point reinforces the opening Participatory section of the PRAAX model and encourages teachers to engage learners as co-musicians in real-life contexts. Similarly, Freire (1970) advocated for education as shared praxis through a participatory learning process where everyone learns and teaches together.

Reflexive

Reflexivity is essential for challenging assumptions, recognising positionality, and cultivating critical pedagogy within music education. Teachers and students should continually reflect on their practice, assumptions, and the sociocultural forces that shape their perspectives on music education. A core tenet of Regelski’s praxial approach is continuous critical reflection on one’s teaching practice. In his work, Regelski likened music teaching to other “helping professions” that regularly reflect on their success or weaknesses as an ethical duty, underlining that reflexivity is key to practical and ethical music education (Regelski 2016, 32). For Freire, only the unity of critical reflection and action can lead to genuine learning and social change (Freire 1970, 79). The Reflexive principle aligns with the idea that music students and teachers must continually question and examine their assumptions and practices as part of the learning process.

Agentic

Agency in the PRAAX model supports students in becoming authors of their own musical and social realities. Students are encouraged to make meaningful musical decisions to develop their capacity to act with confidence and purpose. Regelski highlights that a praxial approach views music education as “a creative source of personal and social agency and meaning” (Regelski 2004, 23) rather than a strictly formal or theoretical pursuit. The goal is for students to become musical agents who can use music meaningfully throughout their lives after leaving the formal requirements of a national curriculum (Regelski 2004). In Cultural Action for Freedom (1972), Freire argued that to participate fully in shaping history, individuals must be able to identify and give voice to their own experiences and realities. In music education terms, these statements highlight the agentic principle: education should enable individuals to claim authorship of their musical and social reality, exercising choice and voice. In a music education context, this means students must have genuine agency in directing their musical learning and creation.

Authentic

Authenticity in music education means rooting learning in the lived realities, values, and interests of students. Learning is rooted in students’ lived experiences and cultural realities. Regelski advocated for authentic music learning experiences that emulated those in real-life musical practices and students’ lived experiences. In practice, this means choosing content and activities that resonate with the students’ cultural realities and their personal musical interests. By focusing on what music is “good for” in human life (rather than treating music as an autonomous art object), Regelski’s praxial approach ensures authenticity and relevance in music education (Regelski 2004, 17). Freire (1970) uses the term authentic to describe education that is co-created with learners in context. An authentic pedagogy in music would thus involve teachers and students collaborating on musical content that reflects students’ lives and communities.

Cross-Cultural

Cross-culturality calls educators to expand the musical canon and support intercultural understanding through inclusive pedagogy. Integrating diverse musical traditions and experiences fosters respect and dialogue across cultures. Regelski emphasised that musical meaning is culturally and socially situated, not universal. Citing research in ethnomusicology and cognitive science, he noted that “what is experienced as ‘emotion’ in one society is not necessarily experienced as ‘emotion’ by another, or not as the same ’emotion,’ or in the same way” (Regelski 2004, 14). This point highlights the importance of understanding music in its cultural context. In line with the cross-cultural principle, Regelski argued against the one-size-fits-all style of curriculum and instead advocated for the inclusion of multiple musical traditions. Freire (1970) emphasised the importance of cultural dialogue, where educators and students learn from each other’s cultural perspectives in the pursuit of mutual humanization. In practice, Freire’s ideas suggest that music educators should not impose a singular cultural canon but rather work with students’ cultural music traditions and those of others. By doing so, the classroom can become a cross-cultural learning space that fosters understanding, respect, and critical dialogue about music from many cultures.

Together, these factors form a vision of music education grounded in praxis. The PRAAX model seeks to understand music education as a space where identity, culture, and voice are recognised and suitable action is taken. Central to both Freire’s and Regelski’s visions is the belief that education should empower students to participate musically in their lives and society. Empowerment, in this sense, is not a fixed outcome but an evolving process of recognising one’s capacity to act, challenge, and transform. Regelski (2004, 2016) positioned music education as a vehicle and tool for lifelong musical engagement through the concept of phronesis. The PRAAX model draws on both visions, aiming to develop students’ capacity to be musically empowered learners, both inside and outside the classroom.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the model emphasises the interconnectedness of these five values. Reflexivity without action could remain theoretical. Authenticity without agency can become appropriative, and cultural inclusion without critical reflection risks reinforcing existing hierarchies. PRAAX challenges educators to balance tensions and treat pedagogy as a living, responsive act.

Figure 2—The PRAAX Model

As a work in progress, PRAAX encourages iterative use. Teachers can try an approach, gather student responses, reflect on the outcomes, and adjust or act accordingly. The five principles serve as planning criteria and an evaluative toolkit. Over time, this process contributes to a more ethically responsive and contextually grounded practice.

Vignette 5—Scaffolding and Equity

Initially, the same confident and experienced players took charge. After discussion, the teacher introduced rotating leadership so that every student, at some point, had to guide the group, and they used reflection sheets to spark honest dialogue about whose voices were being heard and those who were not. The early attempts were hesitant, even awkward, but gradually more students began contributing ideas. Slowly, the dynamic shifted, and more students came forward. Those with experience began to understand the democracy of rehearsal.

To illustrate how PRAAX can inform ethical facilitation in ensemble learning, consider the ways in which power dynamics typically manifest. Teachers recognised that in many student-led projects, musically experienced participants tend to dominate decision-making around repertoire and role allocation. Viewed through the principles of PRAAX, particularly reflexivity and participation, such imbalances call for structures that actively redistribute authority. For instance, rotating leadership roles can ensure that each participant has an opportunity to guide the ensemble. At the same time, group reflection tools can help scaffold dialogue about whose contributions are being acknowledged and those who may be quieter or unheard. These strategies show how ethical facilitation is not a passive stance but an active pedagogical process, one that purposefully initiates conditions for equitable engagement, shared responsibility, and group cohesion.

In the following sections, I further explore the application of the PRAAX model in practice, reflecting on the risks, contradictions, and insights that emerge when attempting to implement it within the constraints of a school system, a system defined by standardisation through a national curriculum, accountability through exam specifications, and curricular rigidity.

Risks and Realities of Enacting PRAAX in Schools

While the PRAAX model may offer an ethically grounded approach to music education and is designed to be responsive, its placement within the formal schooling environment highlights many challenges. Schools remain deeply embedded within cultures of performativity, where accountability metrics, exam specifications, and time restrictions hinder the flexibility required for student-centred learning (Ball 2003; Fautley 2010). Despite teachers’ best intentions, implementing a model that foregrounds both their critical reflections and students’ musical identities risks clashing with institutional expectations.

There are also practical limitations. Using PRAAX in exam classes where specifications are externally set may appear incompatible with curricular pacing and standardised assessment criteria. However, as Regelski (2004) asserted, music education should not be reduced to training for assessment; it must retain its socially embedded, ethical dimensions. Similarly, Freire (1970) warned of the tendency for radical pedagogies to become domesticated through institutional absorption: terms like “student voice” and “co-construction” risk being diluted unless tied to genuine politics of transformation. PRAAX, therefore, must be held as an evolving commitment rather than a rigid formula, sustained through ongoing reflexivity rather than compliance.

An example emerged from the interviews surrounding discussions about a course that teachers reported having previously delivered to 14–16-year-olds. The vocational pathway replaced exam-driven content with personalised project pathways and genre/repertoire flexibility. However, despite its success with learners, the course did not fully match the school’s accountability metrics or formal performance indicators. As a result, the course is no longer being offered to the students. Its discontinuation highlights ongoing tensions between pedagogical innovation and the demands of a meritocratic education system, where the value of a course is often measured not by its impact or relevance to students, but by its alignment with top-down, externally imposed standards.

This tension is particularly prominent in music education, where hegemonic notions of musical value continue to marginalise informal practices and non-canonical genres (Green 2008; Karlsen 2010a; Ricketts 2025). As Bourdieu (1986) warned, dominant forms of cultural capital, such as Western classical musical ideals, are often misidentified as neutral or inherently valuable, making any other approaches appear risky or inferior. Teachers working with PRAAX may face resistance not only from administrative leaders and policymakers, but also from students and parents whose expectations have been shaped by dominant narratives of what constitutes legitimate music education (Spruce 2017).

While the PRAAX model is currently situated with informal and student-directed approaches, its principles are not limited to popular or non-canonical music. In this sense, PRAAX is not anti-canon, but anti-uncritical delivery. Similarly, school music is shaped by a broader exam-driven culture that tends to reward standardisation, measurable outcomes, and compliance with assessment rubrics. This performative pressure can restrict exploratory and student-led practices, especially at key transition points, such as the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE), national exams taken by most students in England at the age of 15–16, or during graded performance coursework requirements. However, it can also be resisted through pedagogical flexibility, by embedding moments of student voice, interpretive choice, or co-assessment within the constraints of formal curricula.

Moreover, reflection and analysis require personal vulnerability and the creation of trusting spaces in which all voices can be heard and validated. As O’Flynn (2005) reminded us, without careful scaffolding, group work and informal learning settings run the risk of reproducing existing hierarchies, particularly along lines of gender, race, or prior musical experience. Teachers must therefore navigate the complexity of facilitating voice without simply abdicating responsibility, a balance that Talbot (2013) identified as central to practitioner-led co-construction.

It is also important to acknowledge that not all students thrive in open or co-constructed environments. Some students express a clear preference for the clarity and security of structured ensembles, where expectations, repertoire, and roles are predefined. In these cases, voice may manifest not through democratic decision-making, but through the initial choice to participate in a particular ensemble tradition. As such, the centring of student voice need not mean dismantling all structure. Instead, it calls for an understanding of how voice is recognised, whether through repertoire negotiation, sectional leadership, or reflective dialogue within existing formats. Likewise, the notion that voice must always be foregrounded as a moral imperative should be carefully considered. At the same time, equity and inclusion demand attention to power and participation; the form that student voice takes can and should vary across contexts, age groups, and musical goals. The PRAAX model is not designed to replace structure, but to critically interrogate when, how, and for whom student voice matters.

PRAAX also requires critical reflection on which students benefit most from open-ended, student-directed approaches. While the model aims to centre all voices, students bring varying levels of confidence and prior experience to the classroom. Those who are confident, outspoken, or musically fluent may find it easier to navigate autonomy. In contrast, others may become disengaged or marginalised in the less structured environments entailed in informal learning. Without intentional scaffolding and ongoing teacher mediation, there is a risk that PRAAX may inadvertently privilege dominant voices, thereby replicating social hierarchies rather than disrupting them. This recognition reinforces the need for reflexive and ethical facilitation, demonstrating that they are essential components of the proposed model. It also reinforces the need not only to promote voice and agency, but also to ensure they are genuinely distributed and inclusive.

Despite these realities, the risks of inaction are arguably greater. Without critically examining their positionalities, pedagogies, and practices, teachers risk allowing exclusionary practices and dominant voices that silence students. PRAAX does not eliminate risk; it reframes it as an ethical necessity, as a condition for meaningful change.

Conclusion: Praxis as Commitment, Not Solution

Regelski (2009) reminded music educators that praxis involves ongoing critical reflection in and on action; such reflection is never finished and never final. PRAAX does not claim to offer a definitive answer to the structural inequities or pedagogical dilemmas that music educators face. Instead, it is intended to serve as a working model of praxis, rooted in Freire’s (1970) insistence that education must be an act of liberation and Regelski’s (2016) framing of music teaching as a form of ethical activism. It is a call to action: to reflect, act, and analyse while continually positioning learning within the broader political and social forces shaping school classroom music.

Throughout this article, we have seen how the components of PRAAX intersect with contemporary music education research and theory. Talbot’s (2013) narrative inquiry into teacher identity, O’Flynn’s (2005) warning against superficial equality, and the affordances of scaffolding in group settings all point to the same conclusion: voice and agency are not guaranteed by intention alone. They must be enacted deliberately, contextually, and ethically.

PRAAX resists the notion that transformation comes from top-down innovation. Instead, it affirms that the teacher-researcher is central to change through cycles of inquiry. These contributions not only contribute to the reform of school music classes but also to the reimagining of what music education might be. In this way, the model aligns closely with the Action Research Spiral (Kemmis and McTaggart 1988) and reinforces that reflective practitioners can imagine and practice systemic rethinking in their classes.

The PRAAX model—Participatory, Reflexive, Agentic, Authentic, and Cross-cultural—offers a flexible, ethically grounded framework for rethinking music education in context. Each principle purposefully challenges the assumption that student agency, voice, cultural relevance, and autonomy emerge naturally. Instead, they must be consciously designed into the learning environment through structured scaffolding, relational pedagogy, and critical reflection. Navigating the tension between open-ended informal learning and systemic pressures has shaped how PRAAX has evolved. It has helped me reframe the structure of the classroom not as an opposition to agency, but as a potential site of dialogue, where teacher intent and student identity can meet in negotiated ways. Rather than prescribing a single method, PRAAX invites educators to engage with the uncertainties of practice as opportunities for co-construction, critique, and meaningful change. In this way, PRAAX is not a model to follow, but a position to inhabit, critically, creatively, and continuously.

Further Research

To extend the PRAAX model, I propose developing a framework for metacognitive musicking, grounded in practitioner inquiry and critical pedagogical theory. This framework recognises that students must possess both technical and musical skills, as well as the reflective capacities needed to make sense of and to make informed decisions within the creative process. Metacognition is thus positioned as both an individual and social competency, enabling students to consider and reflect on how they are learning, why particular choices are being made, and what impact those choices have on others in the class. While this article outlines the inception of PRAAX and its classroom applications, it does not provide an account of how metacognitive skills or knowledge are developed in music education. This represents both a limitation and an opportunity for further investigation.

Further research is required to test and challenge this framework in varied settings, particularly those with differing demographic, cultural, and resourced contexts. Additionally, more work is needed to understand how teachers can be supported in recognising, modelling, and nurturing metacognitive processes without undermining the openness and flexibility that make informal learning so powerful. As such, the next phase of this research will explore how metacognitive musicking can be meaningful and identify the skills required for students to engage democratically with their music education.

Just as this article began by questioning what it means to teach music ethically within constraint, the next phase of this work will examine how metacognitive frameworks can support students and teachers in navigating that terrain with confidence, purpose, and care.

About the Author

Chris Ricketts is a Music Curriculum Leader within a secondary school and the music lead for a multi-academy trust. He is also an EdD candidate at the University of Portsmouth, nearing completion of his thesis, which explores teacher agency and policy influence. His professional background spans performance and education, having previously worked as a cruise ship entertainer, vocalist, and guitarist before moving into classroom teaching and curriculum leadership. His ongoing research explores music curriculum design, teacher and student agency, and the role of co-constructed and dialogic approaches to learning in secondary music education. Drawing on his experience as both practitioner and researcher, Chris’s work seeks to bridge theory and practice by examining how informal and participatory pedagogies can inform more inclusive, relevant, and critically engaged classroom experiences. Through his current articles, Chris continues to contribute to the professional discourse on curriculum, agency, policy and practitioner inquiry in music education.

References

Bamford, Anne. 2006. The wow factor: Global research compendium on the impact of the arts in education. Waxmann.

Barone, Tom, and Elliot W. Eisner. 2012. Arts-based research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Barrett, Margaret S. 2011. Musical narratives: A study of young children’s identity work in and through music-making. Psychology of Music 39 (4): 403–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735610373054

Benton, Carol. 2013. Promoting metacognition in music classes. Music Educators Journal 99 (2): 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432113500077

Bernard, Cynthia F., and Matthew Rotjan. 2021. “It depends:” From narration sickness to wide awake action in music education. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 20 (1): 120–45. https://doi.org/10.22176/act20.1.53

Biddulph, Mary. 2011. Articulating student voice and facilitating curriculum agency. Curriculum Journal 22 (3): 381–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2011.601669

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The forms of capital. In Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education, edited by John Richardson, 241–58. Greenwood.

Bradley, Deborah. 2006. Music education, multiculturalism and anti-racism: Can we talk? Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 5 (2): 2–30. https://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Bradley5_2.pdf

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bull, Anna. 2015. The musical body: How gender and class are reproduced among young people playing classical music in England. PhD diss., Goldsmiths, University of London. https://doi.org/10.25602/GOLD.00012299

Burnard, Pamela. 2012. Musical creativities in practice. Oxford University Press.

Cook-Sather, Alison. 2006. Sound, presence, and power: “Student voice” in educational research and reform. Curriculum Inquiry 36 (4): 359–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-873X.2006.00363.x

Cumberledge, Jason P., and Michael L. Williams. 2023. Representation in music: College students’ perceptions of ensemble repertoire. Research Studies in Music Education 45 (2): 344–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X211066844

Ellis, Carolyn, Tony E. Adams, and Arthur P. Bochner. 2011. Autoethnography: An overview. Forum: Qualitative Social Research 12 (1): Article 10. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-12.1.1589

Ellis, Carolyn, Tony Adams, and Stacy Jones. 2015. Autoethnography: Understanding qualitative research. Oxford University Press.

Evans, Sarah E., Gary Beauchamp, and Victoria John. 2015. Learners’ experiences of informal learning in secondary music in Wales (Musical Futures pilot). Music Education Research 17 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2014.950212

Feichas, Heloisa. 2010. Bridging the gap: Informal learning practices as a pedagogy of integration. British Journal of Music Education 27 (1): 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051709990192

Folkestad, Göran. 2006. Formal and informal learning situations or practices vs formal and informal ways of learning. British Journal of Music Education 23 (2): 135–45. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051706006887

Freire, Paulo. 1970/2000. Pedagogy of the oppressed: 30th anniversary edition. Translated by Myra Ramos. Bloomsbury Academic.

Freire, Paulo. 1972. Cultural action for freedom. Penguin.

Green, Lucy. 2008. Music, informal learning and the school: A new classroom pedagogy. Oxford University Press.

Hess, Juliet. 2017. Decolonizing music education: Moving beyond tokenism. International Journal of Music Education 35 (3): 337–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761415581283

Hess, Juliet. 2020. Finding the “both/and”: Balancing informal and formal music learning. International Journal of Music Education 38 (3): 441–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761420917226

Jaffurs, Sheri E. 2004. The impact of informal music learning practices in the classroom, or how I learned how to teach from a garage band. International Journal of Music Education 22 (3): 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761404047401

Kallio, Hanna, Anna-Maria Pietilä, Martin Johnson, and Mari Kangasniemi. 2016. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. Journal of Advanced Nursing 72 (12): 2954–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13031

Karlsen, Sidsel. 2010a. Immigrant students and the negotiation of multicultural music education in Sweden. Music Education Research 12 (1): 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051710000203

Karlsen, Sidsel. 2010b. BoomTown music education and the need for authenticity—Informal learning put into practice in Swedish post-compulsory music education. British Journal of Music Education 27 (1): 35–46. https://scispace.com/pdf/boomtown-music-education-and-the-need-for-authenticity-gub1max5b4.pdf

Kemmis, Stephen, and Robin McTaggart. 1988. The action research planner. Deakin University.

Ladson-Billings, Gloria. 1995. Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal 32 (3): 465–91. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003465

Ladson-Billings, Gloria. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: aka the remix. Harvard Educational Review 84 (1): 74–84. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.84.1.p2rj131485484751

Leavy, Patricia. 2020. Method meets art: Arts-based research practice. 2nd ed. Guilford Press.

Law, Wing-Wah, and Wai-Chung Ho. 2015. Popular music and school music education: Chinese students’ preferences and dilemmas in Shanghai. International Journal of Music Education 33 (3): 304–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761415569115

Musical Futures. 2022. About us. https://www.musicalfutures.org/about-us

Music Will. 2024. Our approach. https://www.musicwill.org/our-approach

Ng, Heng Huat. 2018. Enabling popular music teaching in the secondary classroom—Singapore teachers’ perspectives. British Journal of Music Education 35 (3): 301–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051717000274

O’Flynn, John. 2005. Re-appraising ideas of musical equality in school music education. International Journal of Music Education 23 (2): 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761405058238

Paris, Django. 2012. Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher 41 (3): 93–97. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12441244

Regelski, Thomas A. 2004. Teaching general music in grades 4–8: A musicianship approach. Oxford University Press.

Regelski, Thomas A. 2009. The ethics of music teaching. In Music education for changing times: Guiding visions for practice, edited by Thomas A. Regelski and J. Terry Gates, 71–82. Springer.

Regelski, Thomas A. 2016. Music, music education, and institutional ideology: A praxial philosophy of musical sociality. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 15 (2): 10–45. https://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Regelski15_2.pdf

Regelski, Thomas A. 2022. Musical value and praxical music education. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 21 (1): 1–40. https://doi.org/10.22176/act21.1.15

Ricketts, Christopher. 2025. Power and policy: Unpacking hegemonic narratives in music education. Journal of Popular Music Education. https://doi.org/10.1386/jpme_00161_1

Spruce, Gary. 2017. The power of discourse: Reclaiming social justice from and for music education. Education 45 (6): 720–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2017.1347127

Talbot, Brent C. 2013. Marginalized voices in music education: A narrative inquiry into the lives of music teachers and students. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 197: 5–22. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315225401

UNESCO. 2010. Seoul agenda: Goals for the development of arts education. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000184657