THOMAS FIENBERG

University of Sydney (Australia)

November 2023

Published in Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 22 (4): 44–78. [pdf] https://doi.org/10.22176/act22.4.44

Abstract: In this article, I examine the potential of social media to meaningfully connect students and educators with First Nations popular musicians. Utilising yarning-as-method under the theoretical frame of storying, I present accounts of attempts to embed the practice in high school classes before exploring how the process was refined for an initial teacher education course under the guidance of Noongar scholar Clint Bracknell. In addition, I share yarns of First Nations artists, who reveal the reciprocal benefits of reaching out and sharing back as a decolonial tool for building relationships and supporting the inclusion of First Nations music. Although centred on an Australian context, I explore themes and pose questions that aim to resonate with a global audience searching for innovative and meaningful ways to embed First Nations cultures into music curricula.

Keywords: First Nations, Aboriginal, yarning, storying, social media, decoloniality, music education, popular music

Warami[1], this yarn is drawn from living and working on Gadigal and Dharug[2] Country[3]. I acknowledge the Gadigal and Dharug peoples as the ongoing Custodians of these unceded Lands in so-called Australia and pay respects to Elders past, present, and emerging. This respect is extended to the First Nations peoples whose knowledge and friendship has guided all stages of the research process.[4]

Student: How are we meant to contact them?[5]

Me: How do you usually talk to people?

Student: Um, using Messenger, Instagram, WhatsApp?

Me: That might be a starting point then. If you need to ask me a question, how do you start?

Student: Email or Facebook DM if it’s urgent, but they’re famous and you’re not!

Me: I’m on YouTube too!

Student: That doesn’t count. What if they don’t respond?

Me: Wait a few days and send another message. Do you know who else played on the record? Try them. Have you emailed their management? The contact details are usually on their Facebook Page or website.

Student: And if that still doesn’t work? Can we still perform the song?

Me: Generally, yes, but it depends on the song and what you want to do with it.

Student: What do you mean by “depends”?

Me: Whose voice are you assuming? Do you know what the song’s about? Why not start up a yarn?

Student: Well, if we’re just going to play it like all the other music we play in class, why even bother reaching out?

These types of questions have remained unchanged since I moved from teaching in a high school classroom to lecturing pre-service teachers at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music. As a non-Indigenous music educator, I empathise with the challenge of reaching out to First Nations artists, particularly if these artists are working in a popular music industry that has long seemed distant to the education sector. Contact, initially through social media, opens dialogue with the artist and facilitates a relational understanding of how music is shared in First Nations cultures. Following a storying methodological approach (Phillips and Bunda 2018), better known within Aboriginal[6] culture as yarning (Bessarab and Ng’andu 2010), I share experiences from high school and university contexts of a strategy that was refined and embedded into an undergraduate music education course by Noongar musician and scholar Clint Bracknell and his non-Indigenous colleague Michael Webb. I also draw upon yarns with First Nations artists, who describe the reciprocal benefits of sharing their music; and the importance of building relationships when performing songs by First Nations musicians. Although centred on the Australian context, this article explores themes and poses questions that aim to resonate with a global audience searching for innovative and meaningful ways to embed diverse First Nations cultures into music curricula.

First Nations Research and the Non-Indigenous Researcher

It is critical to acknowledge the ongoing links between academic research, European imperialism, and colonialism. Equally, as a non-Indigenous academic working in Australia, my position emerges from a place that has prospered as a result of the dispossession and denial of sovereignty for First Nations peoples (Ardill 2013). Māori scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith (1999) contends that “research is probably one of the dirtiest words in the indigenous world’s vocabulary” (1). For her, decolonisation not only challenges the qualitative paradigm, but also seeks a broader agenda that transforms the institution of research. L. T. Smith also emphasises “the importance of retaining the connections between the academy of researchers, the diverse indigenous communities and the larger political struggle of decolonisation,” as any separation would reinforce a colonial approach to education that is “divisive and destructive” (88). Similarly, Rigney (1999) balances First Nations truth-telling about the “extraction, storage, and control over Indigenous knowledges” (109) with recognition of the need for non-Indigenous researchers to continue working in partnership to document “the struggles of Indigenous Australians for genuine self-determination” (117). For Kwaymullina (2016), this suggests “that the concern now for most who engage with Indigenous peoples is not whether this should be done according to best practice ethical standards, but how to go about ensuring this is the case” (440).

Non-Indigenous music educators have written extensively on the challenges of enacting decolonial research. Discussing the relationship between colonisation and philosophical inquiry, Bradley (2012) questions “renditions of praxial music education, critical pedagogy, and multicultural education as potential forms of epistemological colonialism” (427). Cautioning against embracing undertheorized “philosophical nihilism” (427), she calls for music educators to critically analyse philosophy texts and view them as resources for further inquiry and thought. Hess (2018) draws on anti-colonial perspectives to argue for self-reflexivity and interrogation of coloniality from non-Indigenous researchers, with the hope of leading towards a more ethical and participant-driven music education research praxis. Reflecting on the inadequacies of non-Indigenous epistemes when engaging in research with First Nations peoples, Kallio (2020) challenges the Academy to take responsibility to decolonise methodologies and work in relation with others. Similarly, Prest and Goble (2022) assert the need for non-Indigenous scholars to embrace First Nations ways of being, knowing, and doing in order “to ensure they are not complicit in absorption, erasure, selective extraction, and/or appropriation” (208).

Storying and Yarning as a Non-Indigenous Researcher

While Western methodologies are generally concerned with questions of reliability, validity, and theorising judgements, Cree scholar Shawn Wilson (2001) argues that First Nations methods are intrinsically grounded in relational accountability:

When you are relating a personal narrative, you are getting into a relationship with someone. You are telling your (and their) side of the story, and you are analyzing it. When you look at the relationship that develops between the person telling the story and the person listening to the story, it becomes a strong relationship. (178)

The interconnectedness between story and narrative in First Nations research contexts has become increasingly contested. Sobol et al. (2004) suggest the broader methodological legitimacy of narrative attracts scholars and “respectable practitioners … with an interest in appealing to the inclinations of adults in realms of power, prestige, and influence” (2). From an Aboriginal standpoint, Phillips and Bunda (2018) argue the term “narrative” “would be ridiculed and mocked as another white concept that has snuck its way in, to colonise” (4). They theorise storying[7] as a culturally congruent and ethical alternative that exists in all stages of the research process through “propositions/conceptualisations of research, in the gathering of data with others, in the theorising and analysis of data, [to] the presentation of research” (7). Storying challenges researchers to interrogate their “way of being and knowing the world through story” (105).

While storying is not unique to First Nations knowledge systems, its use and function as a research method differs significantly across various First Nations cultures (Kovach 2009). From an Aboriginal perspective, stories carry great power and are “central to processes of cultural maintenance, reclamation, and renewal” (Balla et al. 2023, 23). Within Aboriginal communities, the purposeful telling of stories is better known as yarning (Walker et al. 2014). The phrase “let’s have a yarn” is commonly used when an Aboriginal person wants to talk and exchange information “between two or more people socially or more formally” (Bessarab and Ng’andu 2010, 38). Yarning is embedded into the structures of society, bringing people together “informally to relax and reflect on stories in recent or past history” (Ober 2017, 8). When used in research contexts, yarning draws on Aboriginal ways of knowing and being, compelling researchers to negotiate how information is shared with Aboriginal communities, fostering “culturally safe and just research” (Dean 2010, 6).

In developing one of the first recognised methodological frameworks of yarning (Table 1), Bessarab and Ng’andu (2010) argue the approach empowers Aboriginal peoples to talk freely, leading to “information emerging that more formal research processes may not facilitate” (47). Extending on Bessarab and Ng’andu’s concept of collaborative yarning, Shay (2021) acknowledges that yarning, like the diversity of Aboriginal Nations, is not homogenous. In her research, she associates yarning with the establishment of relational connections to kin, Country, and community, and various modes of listening to each other, ourselves, and our feelings. Drawing upon the emerging body of literature, Shay also promotes the suitability of yarning as a method for both Aboriginal and non-Indigenous researchers. Ultimately, a successful yarn is dependent on the quality of the relationship and trust between the researcher and the participant (Bessarab and Ng’andu 2010).

| Yarning type | Definition |

| Social yarning | Informal conversations that help build trust and relationships throughout the research process. Can include information about anything people feel inclined to share.

|

| Research topic yarning

|

Conversation that is relaxed and interactive, but with a purpose to obtain information relating to the research project. |

| Collaborative yarning

|

When two or more people actively share information about a research project leading to new discoveries and understanding. |

| Therapeutic yarning | When a participant in the process of sharing a story discloses traumatic, personal, or emotional information. The researcher shifts to listener to help empower the participant to rethink their experience in new and different ways. |

Table 1: Types of Yarning (Bessarab and Ng’andu 2010, 40–41).

Within the context of this article, yarning is embedded through self-reflexive accounts of my teaching and learning over the past decade. These stories were informed through ongoing social yarns with First Nations colleagues and friends, alongside more formalised research topic yarning with artists connected to the Solid Ground program—an arts-based mentoring initiative for First Nations students in Western Sydney high schools (Bessarab and Ng’andu 2010; Fienberg and Higgison 2022). Approval was granted from the University of Sydney’s Human Research and Ethics Council to conduct these research topic yarns, with the artists quoted giving their consent for their names to be included in the article. Yarning also lies at the heart of the pedagogical strategy of reaching out. Here, students and teachers build relationships and connect people to the music they listen to and desire to share. Preceding these yarns, I locate how my story led towards writing and collaborating with First Nations peoples, before discussing the evolving place of popular music by First Nations artists in music education.

An Awakening Through Relationships

Following the completion of my undergraduate music education degree, I found myself teaching in a culturally and linguistically diverse high school, not too far from Redfern, an area identified as the heartbeat of Aboriginal Sydney (Norman 2021). I was confronted with a culture vastly different to the one I had experienced as a student—a school with settler heritage in the monocultural outskirts of Sydney. While I was aware that a few students within the large Catholic high school I attended were Aboriginal, the programs they participated in were rarely mentioned publicly. Similarly, after I was accepted into my undergraduate degree at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, my exposure to First Nations peoples remained relatively minimal. In the absence of interpersonal relationships, I attempted to strengthen my understanding from afar, learning through listening to recordings and writing about partnerships between First Nations and non-Indigenous musicians.

When I commenced my first teaching appointment, I quickly worked to establish relationships with students from various cultural groups, holding space[8] for them to participate and express their music traditions (Filipiak 2020). As I prepared to engage more purposefully with the school’s First Nations community, these experiences proved crucial. I took advantage of opportunities to support First Nations students participating in programs coordinated by local community organisations. Through volunteering my time, I built the trust of students, parents, and community facilitators. Critically, the arts were central to the programs, serving as a key tool in fostering cultural solidarity amongst the students and connecting them with their Aboriginal identity. Drawing on my musical training, I was able to transition from being a supervisor to collaborating with First Nations artists during songwriting workshops with students. Despite successful moments, I was very aware of my difference, and the limitations of my engagement. It was clear that my role was to listen deeply and learn alongside my students.

Fears, Problems, and Embracing Popular Music by First Nations Artists

In 1988, a renewed sense of nationalism spread across Australia and Australian music education (Callaway 1988) as the country celebrated 200 years of colonisation. A fleet of tall ships re-enacted the 1788 British invasion of Sydney Cove, accompanied by a flag waving envoy of people watching on the shoreline. Countering the fervour in a special bicentennial issue of the Australian Journal of Music Education, ethnomusicologist Margaret Kartomi (1988) acknowledged the irony of celebrating two centuries of “unmitigated tragedy” (13) with ongoing colonisation leading to significant loss of First Nations languages and pre-colonial musical practices (Corn 2009). In addition to presenting the case for further musicological research and revitalisation of First Nations music traditions, Kartomi (1988) noted that historically, “very little attention [had] been given in Australian schools to [First Nations] music, largely because very few teachers have had the resources and training to teach it” (16).

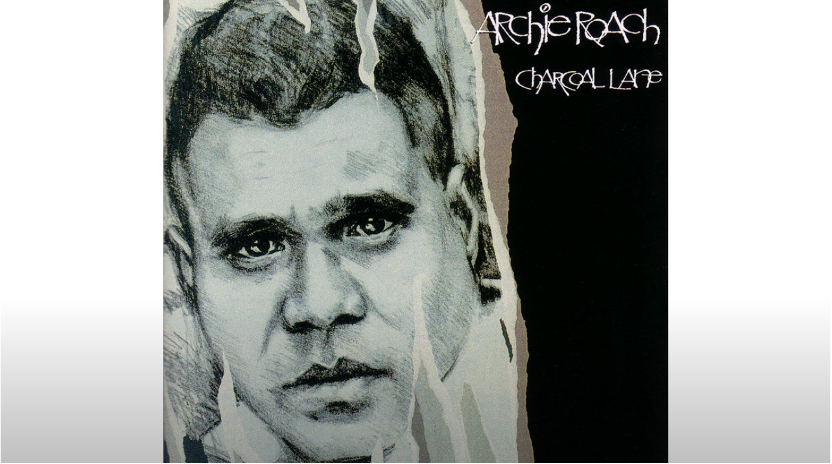

As the bicentennial ships prepared to land, a song that would share harsh truths and influence a new generation of First Nations popular musicians was about to be performed by Archie Roach,[9] a proud[10] Budjalung and Gunditjmara man, to a gathering of predominantly First Nations protesters. In his autobiography Roach reflected on this performance:

When I played [Took the Children Away], I was almost in a dissociative state, but when I finished, I came back to reality. People were stunned. Women were crying. Men had their heads bowed, shoulders heaving. People from all across this Aboriginal nation came up to me at the front of the stage to tell me that my story, my family’s story, was also their story … I was shocked. I was not prepared for how my song affected them. (Roach 2019, 205)

Archie Roach, Took the Children Away https://youtu.be/HNQhCb8xH8E

Archie Roach, Took the Children Away https://youtu.be/HNQhCb8xH8E

Coinciding with Roach’s release of the iconic album Charcoal Lane (Roach 1990), a band named Yothu Yindi emerged from North-East Arnhem Land. Yothu Yindi fused Yolŋu song practice with a variety of popular music styles, which would trigger the first wave of Aboriginal music resource creation that had been called for by Kartomi (Stubington and Dunbar-Hall 1994; Taylor 2007). Often neglected by educators, Yothu Yindi consisted of non-Indigenous and Yolŋu members (Webb and Bracknell 2021), with their hybridity modelling “thinking on the dynamic nature or ‘reinvention’ of tradition” (Wemyss 1999, 32). The music of both Archie Roach and Yothu Yindi provided the ideal avenue for music educators to bring First Nations music, language, and lived experience into the classroom.

Neuenfeldt (1998) argues, “the inclusion of Indigenous popular music in Australian curricula is a small step towards including Indigenous knowledge and viewpoints [to] help sound silences even amidst the cacophony of the new racism” (212). Similarly, Wemyss (1999) describes popular music by First Nations artists as “an essential component of Australian music education,” (28) with the potential to help “develop a positive self-concept in Indigenous students” (32). Further, Wemyss asserts that the commercial nature of popular music allows First Nations voices to be more easily included in the classroom, helping navigate teachers’ fears of misrepresentation and cultural insensitivity. Writing on epistemological and sociological considerations within popular music education, Hebert et al. (2017) question the impact of the capitalist and commercial realities of the popular music industry. Recognising that most popular music releases are actually inevitably unpopular (G. D. Smith 2017), this requires teachers to adopt a critical lens to navigate the dangers of excluding diverse First Nations voices who face inequitable access to a Western, male-dominated industry (Barney 2009). While surveys indicated that schoolteachers were increasing the presence of First Nations music in their classes, concerns were still held about improper pre-service teacher training; a lack of knowledge about First Nations music and cultural protocols; and inadequate resources to teach the music appropriately (Dunbar-Hall 1997; Dunbar-Hall and Beston 2003).

Writing on the attempt to categorise First Nations music, Bracknell (2019) argues “the tag of Indigenous music is reliant on outsider-perceived notions of authenticity and also pigeonholes Indigenous artists as exotic” (103). In an interview for Bracknell’s chapter, Archie Roach commented:

People always talk about me as an Aboriginal singer/songwriter. I say well, ‘I’m a singer/songwriter who just happens to be Aboriginal.’ You know? Sure, I write about the experience of the first nations’ [sic] experience, first peoples’ experience, but you know, like any songwriter I just want to write a good song and hope somebody likes it. (Bracknell 2019, 103)

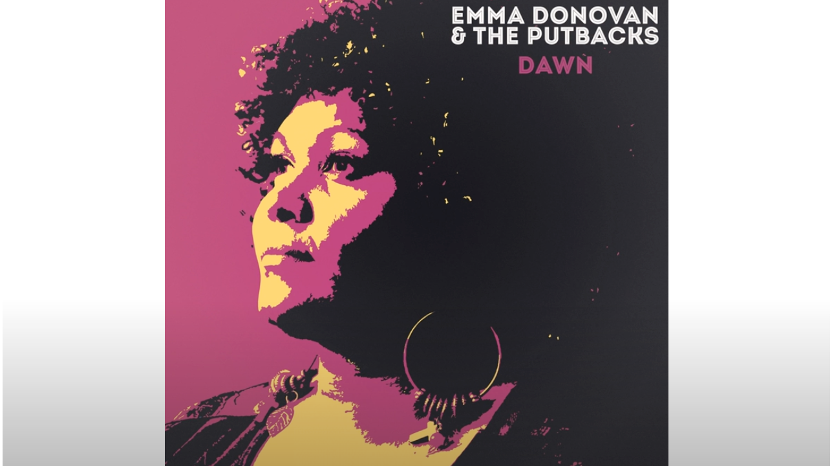

In one of the research topic yarns for this article, Gumbayngirr/Yamatji songwriter and Solid Ground mentor Emma Donovan[11] yarned with me about the evolving place of First Nations artists in the Australian music industry, and reflected on the influence of Archie Roach and his late wife, Ruby Hunter:

Emma Donovan: I used to watch the ARIAs [Australian Recording Industry Association Awards][12]when I was really young and I’d be looking for Aunty[13] Ruby and Uncle Archie there, and they’d be in these categories like “World Music.” [In 2020] Uncle Archie was inducted to the ARIA Music Hall of Fame, but he also won Male Artist of the Year over some real big male artists that we hear in the country. To me, I’m getting teary just thinking about it, sorry, I feel like we’ve come a long way with our music and our representation. Our music is blak[14]music, it’s Aboriginal music, but it shouldn’t be categorised. We should be there amongst everybody else in the industry.

Drawing on interviews with Roach and several other First Nations popular musicians, Bracknell (2019) theorises that First Nations music is not a genre nor homogenous, with artists writing and performing in various popular music genres. While musicians like Roach want their music to be respected in its own right, Bracknell comments that many artists “foreground their Indigeneity as a point of difference to stand out in the crowded Australian music scene” (118). It is increasingly common for artists to proudly emphasise their specific regional cultural identity and connections to Country, whether or not their music makes an explicit political statement or reference to First Nations issues. These affirmations serve to “illustrate cultural diversity to non-Indigenous listeners” (115) and can powerfully link artists “to their ancestors and own community while informing specific socio-cultural relationships with other Indigenous audiences across the continent” (121).

Entering the Mainstream and the Need for Relationship

In my early years as a teacher-researcher, I focused on including the music of a new generation of First Nations artists who were gaining a strong presence in the Australian mainstream media (Fienberg 2011). The R&B music of former Australian Idol runner up Jessica Mauboy,[15] a proud Kuku Yulanji woman, became the catalyst for breaking down students’ stereotypical understanding of First Nations music and its connection to Aboriginalism (Barney 2009). Referring to Mauboy and other prominent First Nations musicians, Guy (2015) notes that their normality makes them complex, countering perceptions of terra nullius (no man’s land) representing “Aboriginalities far from the essentialized imaginings of a temporally distant desert tribesman” (15). By performing her songs for my school’s NAIDOC celebrations,[16] both non-Indigenous and Aboriginal students deepened connections to music they enjoyed, contextualising Mauboy’s music alongside diverse expressions of Blak excellence (Fienberg 2011).

Jessica Mauboy, Been Waiting https://youtu.be/_1UVVUq3X0E

Jessica Mauboy, Been Waiting https://youtu.be/_1UVVUq3X0E

Hess (2018) observes that it is easy for music education scholars to “tell uncomplicated success stories” and “erase contradictions” (578). Critiquing story sharing in music education, Richerme (2021) also argues that “while the educator might retrospectively select the events that they believe most influential in encouraging their changed practices, one can never fully account for the complicated nature of any single moment” (129). Although including First Nations artists in my programming had boosted representation of voices often silenced, preliminary interviews[17] with the non-Indigenous high school students at the centre of my doctoral study (Fienberg 2019) revealed limitations of using popular music to transform understanding. When asked what First Nations music meant to them, the students responded:

Sione[18]: Like didjeridu, like culture music … stuff like that.

Melisa: Storytelling music, but more in depth than normal music… Spiritual stuff.

Louisa: Just like tribal music and stuff… I don’t know… You know those hymns that they do in the desert.

Mele: Like doing cultural music, didjeridus, people dancing in their wares [traditional dress].

Further, when presented with the opportunity to engage with popular music by First Nations artists, Luis’ response revealed a high level of ignorance, reflecting broader racial stereotyping of First Nations peoples in Australia.

Luis: It sounded like something Coldplay would sing. The guy who was playing [guitar] was Aborigine, but he didn’t sound like an Aboriginal was playing that instrument… They [First Nations peoples] rap a lot about government, I’ve noticed. Like just going on around the government and what’s going on. As opposed to American hip hop where they just rap about having a good time, drugs, alcohol or that stuff… I’d rather have a good time than talk about politics.

Critically, these non-Indigenous students’ previous exposure to and experiences of First Nations music had not involved communication with or sharing music with First Nations peoples. In searching for strategies to foster deeper understanding, I turned to Mackinlay (2008) and her theorising on relationship as pedagogy. Mackinlay challenges teachers to look locally for connections, rather than for “resources”:

Is the door to my classroom open, ajar, or closed to the possibility of making space for Indigenous performers to stand alongside me as musicians, singers, and dancers with knowledge to share?… What do I need to do to open the door wider? If my door is still closed, what is stopping me from engaging in relationships with Indigenous Australian people and their musics? (4–5).

While the prospect of Jessica Mauboy and other prominent musicians entering the classroom seemed unlikely, building relationships with emerging First Nations artists presented a stronger chance of success. The strategy paid immediate dividends for my senior music class. When a student discovered that the lyrics for a song by Queensland band Slip-On Stereo could not be found online and became frustrated at having to transcribe the lyrical content, I encouraged them to contact the band directly on their Facebook page. Much to the surprise of the student, the band responded quickly, praising us for covering their music. Through connecting directly with the artists and performing in genres they identified with, students’ understanding began to shift.

Luis: Even though it’s Aboriginal, they can still do pop songs. Just because they’re Aboriginal doesn’t mean they can’t do it.

David: People most probably think of Aboriginal music as just didjeridu and the traditional stuff, but they’re noticing that Aboriginal music branches up into heaps of different genres. It was good to learn that type of song.

Ben: I just think it’s normal music. I don’t think it should be called Aboriginal music. It should just fit into a genre like hip hop or R&B or something.

Slip-On Stereo, Mercury https://youtu.be/8AOyS09bHZk

The following year, I placed a stronger focus on searching for music by First Nations artists living in our local community. Discovering the indie group Pirra, led by proud Luritja woman Jess Beck, I sought to foster a relationship at a local NAIDOC event in which my students were also performing. Inspired by this interaction, we learnt a song by the band, and I sent a Facebook message to invite them to come listen to our cover. A few weeks later Pirra came into the school to play a small set and listen to the students’ rendition of their song alongside other music we had learnt by First Nations artists. While the students were obviously excited to see them play with our instruments and in our space, Pirra were equally interested in the songs the class shared, demonstrating a mutually beneficial exchange. The diversity of First Nations artists covered by the students led to lead singer Jess openly sharing how Luritja culture lives through her music and her personal reticence of incorporating language without significant learning/guidance from Elders. As popular musicians entering the music classroom, the band also challenged expectations and essentialized perceptions of First Nations culture bearers (Hess 2013).

Pirra. Rose Coloured Glasses https://youtu.be/6MFNg5c-zH0

Pirra. Rose Coloured Glasses https://youtu.be/6MFNg5c-zH0

Connecting with Pirra reinforced the decolonial possibilities (Mignolo 2011) of reaching out and sharing back. Writing on decoloniality in music education, Mackinlay (2016) compels teachers to consider “what kinds of interferences are needed to start to make decolonial moves and am I prepared to make space for them?” (224). Without the ability to reach out through social media, the face-to-face interaction with Pirra would not have been possible. As an “interference,” social media also helped foster a sustainable ongoing relationship, enabling the band to engage as much (or as little) as they wished with me. While Pirra’s rising local profile made it difficult to replicate the workshop experience for future classes, we have continued to regularly exchange messages, sharing student performances, lyrics, and contextual details about various new releases.

Constructing the “Sell the Song” Assignment for Pre-Service Teachers

In 2016, Clint Bracknell and Michael Webb introduced the Sydney Conservatorium of Music’s first music education course in First Nations music. I was fortunate to contribute to its development, and I taught in the course as a guest before coordinating the unit in 2019 and taking over permanently in 2021. It remains one of only two courses in the entire institution that concentrate solely on the music of First Nations peoples. Commenting on the scarcity of representation of courses across Australian universities, Bracknell and Barwick (2020) argue that “without a dramatic cultural shift, these institutions will continue to essentialize, gloss over, and ultimately repel Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and musics” (75).

Writing collaboratively on the themes that impacted the course’s philosophy and structure, Webb and Bracknell (2021) observe that “the Australian Indigenous musical landscape is more diverse and complex today than it has been at any previous time” (76–77), offering teachers broader repertoire options and more points of entry. They encourage teachers to acknowledge the specific regional cultural affiliations of artists and promote an “integrative approach,” where the music’s “sonic properties can be studied [alongside] examples from any other historical-cultural tradition” (Webb and Bracknell 2021, 78).

To ensure the respectful inclusion of First Nations music, Webb and Bracknell (2021) ask teachers to consider and identify the music’s intended audience(s) and function(s) (Figure 1). The most general domain, Nation/World, includes music that communicates First Nations perspectives and cultural survival. The Indigenous domain features music “composed with the intention of maintaining Indigenous group solidarity through shared experiences and perspectives” (80). Music from this domain primarily addresses First Nations peoples identifying with lyrics that explore Indigenous identity and belonging. The third level is “music created by and for Local Mob,[19] which may or may not be restricted in audience terms to members of that community” (81). Critically, Webb and Bracknell compel teachers to consult with First Nations artists and communities to learn about the music’s context, noting that commercially available music can be found within all domains.

Figure 1. Intended audience(s) for First Nations music, as well as its key function(s)

(Webb and Bracknell 2021, 79).

Modelling the process of selecting repertoire and engaging in consultation, Bracknell and Webb devised the “Sell the Song” assessment task. Working in pairs, pre-service teachers select a song to perform by a First Nations artist and are required to contact them for additional information and permission. Pre-service teachers are encouraged to use social media platforms as a starting point for yarning or to engage directly with management associated with the artist. This practice models the Australia Council for the Arts’ (2019) Protocols for Using First Nations Cultural and Intellectual Property. The protocols specify that projects involving commercial adaptation of First Nations content must gain “cultural permissions to use the material and find out its context” (43). While the process for obtaining consent for performing or adapting copyrighted recordings corresponds with broader intellectual property laws, the protocols also acknowledge that many First Nations musicians are not members of copyright societies and it “may be necessary to contact them directly” (46). For songs in First Nations languages, the protocols also recommend consultation with “the relevant language group” (46). At the heart of the protocols is recognition that First Nations artistic and creative expressions are “important ways of storytelling, transmitting knowledge, preserving, celebrating, and expressing culture and languages, reclaiming and maintaining culture, as well as passing culture down to future generations and raising awareness about Indigenous issues” (7).

In my first year of leading the aforementioned course, pre-service teachers covered a range of songs from the nation/world and Indigenous domains with varying levels of dialogue with the artists. Of the 7 artists contacted, 3 communicated directly back through social media, while another group performing a Jessica Mauboy song received approval and advice from her management. By sharing the evidence of reaching out to the class, pre-service teachers who did not receive a response were able to hear the success of others and visibly see its impact on their engagement, thus leading to a collective desire to continue building relationships with First Nations musicians. Through the pre-service teachers’ efforts, I too was able to learn new strategies and consolidate relationships with the artists who communicated back.

Reaching Out from the Perspective of First Nations Musicians

Having completed my doctorate in 2019 and moved on from the school at the centre of my dissertation, I was incredibly fortunate to stumble into a new project. The Solid Ground Artist in Residence program connects First Nations artists with school students in Western Sydney (Fienberg and Higgison 2022). Through the program, I was able to work alongside a variety of musicians, including Emma Donovan, Gamilaraay singer-songwriter Thelma Plum,[20] and Wiradjuri and Ni-Vanuatu woman Evie J Willie.[21] This presented a unique opportunity to discuss some of my pedagogical strategies and to yarn about the impact of reaching out from an artist’s perspective. For Emma, responding to requests from students and schools formed an important part of her responsibility as a member of the First Nations music community.

Emma Donovan: I get lots of emails and lots of messages from people that want my lyrics, or asking if somebody can perform a dance to my song, or asking if someone can cover it. That’s a huge honour for me because I know that people are listening to them stories and they have a connection with it, or they want to participate in this relationship. It’s separate to what I do, you know, gigging or writing music, recording music out there in festivals and that. This is another part of my role, of my responsibility, and the way I want Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander music to be heard from everyone. I’m a big advocate for that and I think we have a lot to say. I think we have some beautiful messages and stories, and I think in this country we should be sharing and celebrating it together.

As part of the Solid Ground program, the mentors would regularly teach songs by other First Nations artists. For Emma, sharing stories from the Indigenous domain (Webb and Bracknell 2021) was critically important in identity formation, particularly for students disconnected from their culture due to the ongoing impact of colonisation.

Emma Donovan: A lot of these young fellas[22]identify as Aboriginal, but there’s that conversation about them not feeling that confident—as a young Indigenous student in school, society, and even probably in their home. So, I wanted to pick a few songs to start with; that kind of meant a lot to me. I think a song like “Yil Lull” was a good place to start.

Joe Geia, Yil Lull https://youtu.be/a8o0KgSiM-o

Joe Geia, Yil Lull https://youtu.be/a8o0KgSiM-o

After the students learnt the opening two verses of Joe Geia’s[23] (1988) anthemic “Yil Lull,” Emma asked the students to envisage a new verse incorporating their own perspectives as young First Nations peoples. Reaching out to Joe was a must, providing the students with a lasting memory and deeper connection to the song.

Emma Donovan: The kids FaceTimed him and he was yarning to them … They loved it. Straight up, everyone should know Uncle Joey [Joe] Geia. He’s a really strong Kuku Yalanji and Torres Strait Islander man. The first thing he wanted to do was tell the kids what Yil Lull meant [“to sing”]. I’d never seen them that quiet actually. He quickly gave them a little idea of the song … After going over the lyrics of the verses, I kind of got them to imagine what it would be like if there was a third verse, and we sang it to Uncle Joey.

Emma’s strategy of sharing influential songs by First Nations artists continued the following year, as the students covered the late Dr G Yunupingu’s[24] (2008) “Bapa” under the mentorship of Evie J Willie and Wiradjuri/Weilwan choreographer Neville Williams Boney.[25] While I had received permission from Dr G’s management, Evie felt the need to speak directly with his daughter, especially as the students’ collaboration was about to be widely shared by the New South Wales Department of Education (2020). For Neville, the process of reaching out was not as challenging as many teachers might think:

Neville Williams Boney: The information I get back from teachers or people who are doing First Nations stories or whatever … they’re like, “we don’t know what to do. Like, it’s too hard so we just won’t do it.” But in my mind, it’s not that hard. It’s literally just a phone call and having a yarn. It’s that simple. It’s not like a form that you have to fill out for the council, and you have to wait three months later and get approved. It’s literally just a phone call, an email, or a call out just to talk to a First Nations person.

“Sell the Song” with Non-Indigenous High School Students and Emma Donovan

Having taught the pre-service music education course, I was eager to implement a larger scale version of this activity in a school context. While Webb and Bracknell (2021) preferred an integrative approach to including the music of First Nations artists alongside related global popular music traditions, my classroom experiences had demonstrated the benefits of programming First Nations music as a unit of work in its own right. In what would turn out to be my final year working as a high school teacher, I curated a concert for NAIDOC week in collaboration with the Solid Ground program and my senior music class (all of whom were non-Indigenous). Working in small groups, the music students prepared songs by 10 First Nations artists, including Emma Donovan who had agreed to perform her song “Over Under Away” (Emma Donovan and the Putbacks 2017) with one of the students. The impact of standing alongside these non-Indigenous students in the NAIDOC event was not lost on Emma as she introduced herself at the beginning of the concert.

Emma Donovan: I think what’s important for me as an Aboriginal artist and Aboriginal woman is to see non-Aboriginal people singing Aboriginal music, and it’s really important for me that it’s shared, and that people are acknowledging Aboriginal voice.

Emma Donovan and the Putbacks, Over Under Away https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i2B1uJKoJtE

Emma Donovan and the Putbacks, Over Under Away https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i2B1uJKoJtE

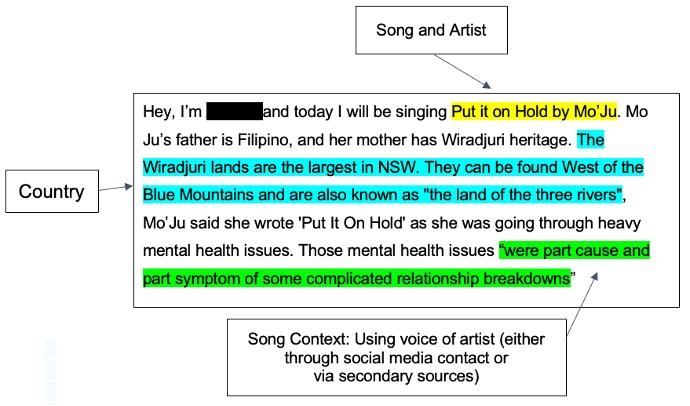

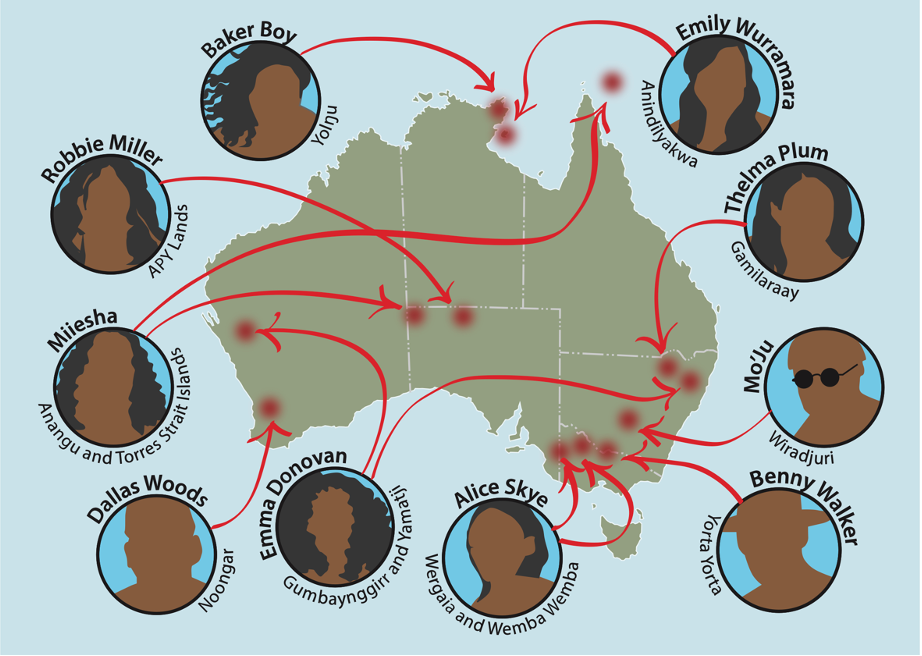

Mirroring the reach out component of this activity, I asked students to contact the artist and write a description of the song they were performing. While not everyone received a response, they were each able to find out about the artist’s regional identity and song meaning through further research (Figure 2). With the pandemic limiting attendance, we filmed the outdoor concert and combined it with video introductions to the songs. Here students narrated their script to footage of the artist performing and a title slide with the name of the song, artist, and a map of their Country. Beyond acting as a transition, these videos constructed a modern day songline[26] (Neale and Kelly 2020), acknowledging cultural survival through the diversity of Nations and voices represented (Figure 3). This “homework” clearly left an impact on Emma who sat in the audience filming the performances and sharing them back to her friends in the industry.

Emma Donovan: I couldn’t believe it. I was blown away. I was blown away even more that there were kids there that weren’t a part of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community that had done their homework, put all this effort into learning Indigenous songs. Just the actual content of the songs too. They were by an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artist and these kids had a go at it. Their confidence and the way they wanted to express it just touched me. There were a few times where I did get teary. I was just really touched … I think from my experiences, all these years I’ve been writing and putting music out, there’s always been that conversation of “Doesn’t matter what I want to write about, any topic. My music is Blak music. It’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander music. It doesn’t have to sound like a specific way.” And I think the thing that I loved most about that concert was the content and the way that the children chose their songs. Just to hear that they’d done their research, found out just where this artist was from, who was their mob, who was their Country. That was the stuff that hit home.

Figure 2. “Sell the Song” assignment: connecting music with Country and the artist’s voice.

Figure 3. NAIDOC concert songline (NB: artist images are hyperlinked to verified Spotify pages for further listening and contextual information[27]).

Figure 3. NAIDOC concert songline (NB: artist images are hyperlinked to verified Spotify pages for further listening and contextual information[27]).

https://bit.ly/NAIDOCsongline

Cartography by Brenda Thornley.

As this article was nearing publication, Emma Donovan released her new solo single “Blak Nation” (Donovan 2023b). The song typifies the sentiment shared in our yarn together and the impact of holding space for First Nations voices; and acknowledging Country in music education. Fittingly, Emma shared the meaning of the song through her social media accounts:

Lyrically Blak Nation is about a cultural practice called back burning, we make a cool fire to promote regrowth. The “cool fire” is reference to the new generation. Bringing the Blak Nation to front of this nation, new artists continuing to tell their powerful stories …

I’m proud of the progress we have made as a nation. Seeing Aboriginal names of Country and People shared.

To see all kinds of people acknowledging traditional places where they live and work. This didn’t happen for my old people and even me growing up, it’s good to see it more now (Donovan 2023a).

Emma Donovan, Blak Nation https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67fEA7U_Lpg

Continuing to “Sell the Song” to Pre-Service Teachers

After being entrusted to continue the work of Bracknell and Webb in a full-time capacity, I am obligated to continue engaging in consultation as the course evolves and responds to the desires and needs of First Nations artists. Through this activity, pre-service teachers and their future students are introduced to a strategy that scaffolds relationship building in a real-world, practice driven method. With the prevalence of social media in our daily-lived experience, reaching out to yarn in this context blurs the boundaries between formal, non-formal, and informal learning (Schippers 2020). Waldron et al. (2020) remind us that “as music educators, we must recognize, challenge, question, and take advantage of the opportunities for music teaching and learning available to us in a digitally networked society. Otherwise, we risk irrelevancy” (14).

The corporate reality of social media’s role in artist promotion and engagement (Partti 2020) has led to a higher response rate in recent years. Unfortunately, the instances of direct contact with artists have decreased as social media accounts shift to being controlled by management companies. This brings into question the extent to which meaningful relationships can be initiated and sustained through reaching out online (Bates and Shevock 2020). Rather than an impediment, I see this as an opportunity to yarn with local and emerging artists regularly profiled in First Nations curated streaming playlists[28] and community events. Despite continually promoting this localised approach, large numbers of pre-service teachers continue to select songs by artists with higher profiles, drawing generic approvals accompanied by instructions to learn more about the songs through online sources. Some managers have even begun commenting on the volume of requests relating to assignments, leading me to consider the impact of larger scale implementation of the strategy in school contexts.

To conclude, I will share one final anecdote from recent conversations with a pre-service teacher. All semester, she had been telling me about how excited she was to attend a concert by Wergaia/Wemba Wemba musician Alice Skye. Despite failing to receive a response from Skye during her assignment, the pre-service teacher persisted in reaching out to members of her band, eventually sharing the video of her group’s performance. Much to her amazement, Skye responded a few months later and posted the students’ cover with permission on her public Instagram page. Fast-forwarding to the concert held earlier this year, the pre-service teacher articulated that she suddenly understood cultural solidarity as she stood alongside several of the First Nations artists covered by other pre-service teachers in the class. While she was too scared to initiate a conversation with any of them, she has been proudly wearing merchandise and sharing with friends the reasons why she went to the concert and who else was there. Making contact matters, and as we globally search for ways to promote the voices of First Nations artists, the simple act of reaching out and sharing back presents an opportunity for us to build relationships that have the capacity to be mutually beneficial; and lead towards greater confidence in sharing incredible music and stories with a new generation of students.

About the Author

Thomas Fienberg is a lecturer in music education and Acting Associate Dean Indigenous Strategy and Services at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, The University of Sydney. His teaching and research interests include Indigenising and decolonising music education, industry and community collaboration in arts-based learning, culturally relevant pedagogy, and First Nations research methods. Thomas worked previously as a secondary teacher in NSW Government schools and was nominated for the Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA) Music Teacher Award in 2020. His research has been published in a variety of academic books and journals, including Research Studies in Music Education, Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education, and the Australian Journal of Music Education.

References

Ardill, Allan. 2013. Australian sovereignty, Indigenous standpoint theory and feminist standpoint theory. Griffith Law Review 22 (2): 315–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10383441.2013.10854778

Australia Council for the Arts. 2019. Protocols for using First Nations cultural and intellectual property. 3rd ed. Australia Council for the Arts. https://australiacouncil.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/protocols-for-using-first-nati-5f72716d09f01.pdf

Australian Government. 2023. Australian Government Style Manual Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Last modified July 5, 2023. https://www.stylemanual.gov.au/accessible-and-inclusive-content/inclusive-language/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples

Baker Boy. n.d. Baker Boy. Spotfiy artist profile. https://open.spotify.com/artist/6Qpa8xhGsGitz4WBf4BkpK?si=ctd0AsqMQwCwpRIfd_47FQ

Balla, Paola, Karen Jackson, Rowena Price, Amy F. Quayle, and Christopher C. Sonn. 2023. Blak women’s healing: Cocreating decolonial praxis through research yarns. Peace and Conflict 29 (1): 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000637

Barney, Katelyn. 2009. Hop, skip, and jump: Indigenous Australian women performing within and against Aboriginalism. Journal of Music Research Online 1: 1–19.

Bates, Vincent C., and Daniel J. Shevock. 2020. The good, the bad, and the ugly of social media in music education. In The Oxford handbook of social media and music learning, edited by Janice L. Waldron, Stephanie Horsley, and Kari K. Veblen, 618–44. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190660772.013.36

Beetson, Alethea. n.d. Deadly beats. Spotify public playlist. https://open.spotify.com/playlist/37i9dQZF1DX9Fa6hiuwYEH?si=d681db9617434e34

Bessarab, Dawn, and Bridget Ng’andu. 2010. Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies 3 (1): 37–50. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcis.v3i1.57

Bracknell, Clint. 2019. Identity, language and collaboration in Indigenous music. In The difference identity makes: Indigenous cultural capital in Australian cultural fields, edited by Tim Rowse, Lawrence Bamblett, and Fred R. Myers, 100–25. Aboriginal Studies Press.

Bracknell, Clint, and Linda Barwick. 2020. The fringe or the heart of things? Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander musics in Australian music institutions. Musicology Australia 42 (2): 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/08145857.2020.1945253

Bradley, Deborah. 2012. Good for what, good for whom?: Decolonizing music education philosophies. In The Oxford handbook of philosophy in music education, edited by Wayne Bowman, Ana Lucía Frega, 408–33. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195394733.013.0022

Callaway, Frank. 1988. Forward. Australian Journal of Music Education (1): 2.

Corn, Aaron. 2009. Reflections & voices: Exploring the music of Yothu Yindi with Mandawuy Yunupingu. Sydney University Press.

Dean, Cheree. 2010. A yarning place in narrative histories. History of Education Review 39 (2): 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1108/08198691201000005

Donovan, Emma. 2023a. My new solo single BLAK NATION is out today! Instagram, October 11. https://www.instagram.com/p/CyPIl4FBJ2-/

Donovan, Emma. 2023b. Blak Nation. October 25. YouTube video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67fEA7U_Lpg

Donovan, Emma. n.d. Emma Donovan. Spotify artist profile. https://open.spotify.com/artist/1zq7VkmDHaXYNCqnNeJvLs?si=1408c3f7ee0b42d4

Dunbar-Hall, Peter. 1997. Problems and solutions in the teaching of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander music. Australian Society for Music Education XI National Conference proceedings: New sounds for a new century, 81–87. Australian Society for Music Education.

Dunbar-Hall, Peter, and Pauline Beston. 2003. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander musics in Australian music education: Findings of a national survey. Conference proceedings: Over the top: The impact of cultural learning in our own and neighbouring communities in the evolution of Australian music education, 50–54. Australian Society for Music Education.

Emma Donovan and the Putbacks. 2017. Over Under Away. February 12. YouTube video. 4:58. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i2B1uJKoJtE

Fienberg, Thomas. 2011. Indigenous culture in the mainstream: Approaches and attitudes towards Indigenous popular music and film in the junior secondary classroom. In Making sound waves: Diversity, unity, equity: Proceedings of the XVIII National Conference, 182–88. Australian Society for Music Education.

Fienberg, Thomas. 2019. Collaboration, community and co-composition: A music educator’s ethnographic account of learning (through and from) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander music. PhD diss., The University of Sydney. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/20791

Fienberg, Thomas, and Debbie Higgison. 2022. Finding Solid Ground: Industry collaboration and mentoring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students in secondary schools. In Musical collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Australia: Exchanges in the third space, edited by Katelyn Barney, 109–21. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003288572-8

Filipiak, Danielle. 2020. Holding space: Centering youth identities, literacies, & epistemologies in teacher education. The Review of Education, Pedagogy and Cultural Studies 42 (5): 451–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2021.1880856

Geia, Joe. 1988. Yil Lull. Track 6 on Yil Lull. Gammin Records, Spotify. https://open.spotify.com/track/0pgtq2mOAY2CguOyYUNpjJ?si=bb789624b97b461b

Geia, Joe. n.d. Joe Geia. Spotify artist profile. https://open.spotify.com/artist/0oWWZ8j5QnyWVySzrNP26h?si=J2Gf7y1kTqmOhfUvKdQNVg

Geia, Joseph. 2014. Joe Geia Yil Lull 1988. August 25. YouTube video, 4:19. https://youtu.be/a8o0KgSiM-o

Guy, Stephanie. 2015. Bodies, myth and music: How contemporary Indigenous musicians are contesting a mythologized Australian nationalism. eSharp 23: 1–21.

Hazel, Yadira Perez. 2018. Bla(c)k lives matter in Australia. Transition, 126: 59–67. https://doi.org/10.2979/transition.126.1.09

Hebert, David G., Joseph Abramo, and Gareth D. Smith. 2017. Epistemological and sociological issues in popular music education. In The Routledge research companion to popular music education, edited by Matt Brennan, Gareth D. Smith, Zack Moir, and Pil Kirkman, 451–78. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315613444-35

Henningham, Mandy. 2021. Blak, bi+ and borderlands: An autoethnography on multiplicities of Indigenous queer identities using borderland theory. Social Inclusion 9 (2): 7–17. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v9i2.3821

Hess, Juliet. 2013. Performing tolerance and curriculum: The politics of self-congratulation, identity formation, and pedagogy in world music education. Philosophy of Music Education Review 21 (1): 66–91. https://doi.org/10.2979/philmusieducrevi.21.1.66

Hess, Juliet. 2018. Challenging the empire in empir(e)ical research: The question of speaking in music education. Music Education Research 20 (5): 573–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2018.1433152

Kallio, Alexis A. 2020. Decolonizing music education research and the (im)possibility of methodological responsibility. Research Studies in Music Education 42 (2): 177–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X19845690

Kartomi, Margaret J. 1988. “Forty thousand years”: Koori music and Australian music education. Australian Journal of Music Education (1): 11–28.

Kovach, Margaret. 2009. Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations, and contexts. University of Toronto Press.

Kwaymullina, Ambelin. 2016. Research, ethics and Indigenous peoples: An Australian Indigenous perspective on three threshold considerations for respectful engagement. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 12 (4): 437–49. https://doi.org/10.20507/AlterNative.2016.12.4.8

Mauboy, Jessica. 2009. Jessica Mauboy—Been Waiting. November 16, 2009. YouTube Video, 3:42. https://youtu.be/_1UVVUq3X0E

Mackinlay, Elizabeth. 2008. Making space as white music educators for Indigenous Australian holders of song, dance, and performance knowledge: The centrality of relationship as pedagogy. Australian Journal of Music Education (1): 2–6.

Mackinlay, Elizabeth. 2016. A diffractive narrative about dancing towards decoloniality in an Indigenous Australian studies performance classroom. In Engaging First Peoples in arts-based service learning: Towards respectful and mutually beneficial educational practices, edited by Brydie-Leigh Bartleet, Dawn Bennett, Anne Power, and Naomi Sunderland, 213–26. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22153-3

Mignolo, Walter. 2011. The darker side of Western modernity: Global futures, decolonial options. Duke University Press.

Miiesha. 2020. Nyaaringu. EMI Australia. Spotify. https://open.spotify.com/album/4FPYLkPm1ri9vaxdGAOMuR?si=mnaiF9UkSje7STuToWCIAg

Miiesha. n.d. Miiesha. Spotify artist page. https://open.spotify.com/artist/1ehGGQnc7E28DNwhvnFuyL?si=72116f38316746ea

Miller, Robbie. n.d. Robbie Miller. Spotify artist page. https://open.spotify.com/artist/0lkWoQLsP4QWkqefjR9IH1?si=ec7cf57ef2374ad0

Mo’Ju. 2018. Native Tongue. ABC Music. Spotify. https://open.spotify.com/album/4eIPiC26JL1CijhjXwlFzs?si=8V546ztQSpizbXmvvla9Jw

Mo’Ju. n.d. Mo’Ju. Spotify artist page. https://open.spotify.com/artist/08kSC3EyOASw4LU1BmBG6g?si=gU9os8ybT5qbvVQO2v6FkA

Neale, Margo, and Lynne Kelly. 2020. Songlines: The power and promise. Thames & Hudson Australia Pty Ltd.

Neuenfeldt, Karl. 1998. Sounding silences: The inclusion of Indigenous popular music in Australian education curricula. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 19 (2): 201–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/0159630980190205

New South Wales Department of Education. 2020. Student musical tribute to Dr G. News. Last modified June 3, 2020. https://education.nsw.gov.au/news/latest-news/student-musical-tribute-to-dr-g

Nicol, Emily. n.d. Blak Australia. Spotify Public Playlist. https://open.spotify.com/playlist/37i9dQZF1DX8GpAnQzW8gR?si=b6928b2d7705473a

Norman, Heidi. 2021. Aboriginal Redfern “then and now”: Between the symbolic and the real. Australian Aboriginal Studies 1: 22–35.

Ober, Robyn. 2017. Kapati time: Storytelling as a data collection method in Indigenous research. Learning Communities: International Journal of Learning in Social Contexts 22: 8–15.

Partti, Heidi. 2020. Reports from the field: The multiple affordances of social media for classical music composers. In The Oxford handbook of social media and music learning, edited by Janice L. Waldron, Stephanie Horsley, and Kari K. Veblen, 227–35. Oxford University Press. https://doi-org /10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190660772.013.13

Pirra. 2014. Pirra—Rose Coloured Glasses (Official B-Side Video). August 10. YouTube video, 3:59. https://youtu.be/6MFNg5c-zH0

Plum, Thelma. 2019. Better in Blak. Warner Music Australia, Spotify. https://open.spotify.com/album/0QuumkXPKBWR7wOKUfqQ34?si=ITXErpXjRkipZc8CxgZ9-w

Plum, Thelma. n.d. Thelma Plum. Spotify artist profile. https://open.spotify.com/artist/0C6qzW0Am8OVyHSoT57fnC?si=a2vs75bgTb2Km4DUgIwt9A

Phillips, Louise G., and Tracy Bunda. 2018. Research through, with and as storying. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315109190

Prest, Anita, and Scott J. Goble. 2022. Decolonizing and Indigenizing music education through self-reflexive sociological research and practice. In Sociological thinking in music education, edited by Carol Frierson-Campbell, Clare Hall, Sean Robert Powell, and Guillermo Rosabal-Coto, 203–16. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197600962.003.0015

Roach, Archie. 1990. Took the children away. Track 6 on Charcoal Lane. Mushroom Records, Spotify. https://open.spotify.com/track/2PolnevtHIyrxe6CjWYpXx?si=3cd51f58e3e049e8

Roach, Archie. 2015. Took the children away. August 8. YouTube video, 5:24. https://youtu.be/HNQhCb8xH8E

Roach, Archie. 2019. Tell me why: The story of my life and my music. Simon & Schuster Australia.

Richerme, Lauren K. 2021. Narrative is not emancipatory, but affective moments might be. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 20 (4): 124–25. https://doi.org/10.22176/act20.3.124

Rigney, Lester-Irabinna. 1999. Internationalization of an Indigenous anticolonial cultural critique of research methodologies: A guide to Indigenist research methodology and its principles. Wíčazo Ša Review 14 (2): 109–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/1409555

Schippers, Huib. 2020. Forward. In The Oxford handbook of social media and music learning, edited by Janice L. Waldron, Stephanie Horsley, and Kari K. Veblen, v–vii. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190660772.001.0001

Shay, Marnee. 2021. Extending the yarning yarn: Collaborative yarning methodology for ethical Indigenist education research. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 50 (1): 62–70. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2018.25

Skye, Alice. n.d. Alice Skye. Spotify artist profile. https://open.spotify.com/artist/0vi9khHSAwMRQx1R65dIFR?si=k1OJTllHQ3mCYVFjSiScIQ

Slip-On Stereo. 2013. Slip-On Stereo—Mercury [Official Music Video]. August 29. YouTube video. 3:52. https://youtu.be/8AOyS09bHZk

Smith, Gareth D. 2017. (Un)popular music making and eudaimonism. In The Oxford handbook of music making and leisure, edited by Roger Mantie, and Gareth D. Smith, 151–68. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190244705.013.31

Smith, Linda T. 1999. Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples. Zed Books.

Sobol, Joseph, John Gentile, and Sunwolf. 2004. Once upon a time: An introduction to the inaugural Issue. Storytelling, Self, Society 1 (1): 1–7.

Stubington, Jill, and Peter Dunbar-Hall. 1994. Yothu Yindi’s “treaty”: Ganma in music. Popular Music and Society 13 (3): 243–59. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143000007182

Taylor, Timothy D. 2007. Beyond exoticism: Western music and the world. Duke University Press.

Walker, Melissa, Bronwyn Fredericks, Kyly Mills, and Debra Anderson. 2014. ‘Yarning’ as a method for community-based health research with Indigenous women: The Indigenous women’s wellness research program. Health Care for Women International 35 (10): 1216–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2013.815754

Walker, Benny. n.d. Benny Walker. Spotify artist profile. https://open.spotify.com/artist/7vkMTeJB89xakcCt1kaU0W?si=sJ3PT-IDQ1iDbT_RCv4NTQ

Waldron, Janice L., Stephanie Horsley, and Kari K. Veblen. 2020. Introduction: Why should we care about social media? In The Oxford handbook of social media and music learning, edited by Janice L. Waldron, Stephanie Horsley and Kari K. Veblen, 1–17. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190660772.013.42

Webb, Michael, and Clint Bracknell. 2021. Educative power and the respectful curricular inclusion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander music. In The politics of diversity in music education, edited by Alexis Anja Kallio, Heidi Westerlund, Sidsel Karlsen, Kathryn Marsh, and Eva Sæther, 71–86. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65617-1_6

Wemyss, Kathryn L. 1999. From T.I. to Tasmania: Australian Indigenous popular music in the curriculum. Research Studies in Music Education 13 (1): 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X9901300104

Wilson, Shawn. 2001. What is Indigenous research methodology? Canadian Journal of Native Education 25 (2): 175–79.

Woods, Dallas. n.d. Dallas Woods. Spotify artist profile. https://open.spotify.com/artist/7AlRsfXxw5GcXNob86rgnH?si=ae4b49e68f374660

Wurramara, Emily. 2018. Milyakburra. Mushroom Music Publishing, Spotify. https://open.spotify.com/artist/0OKjEr4iSUvgGSebJakjNF?si=-JVFnFukQniP2IMuGnPO8A

Wurramara, Emily. n.d. Emily Wurramara. Spotify artist profile. https://open.spotify.com/artist/0OKjEr4iSUvgGSebJakjNF?si=-JVFnFukQniP2IMuGnPO8A

Yunupingu, Dr G. 2008. Bapa. Track 3 on Gurrumul. Skinnyfish Music, Spotify. https://open.spotify.com/track/3oTqeCB3j5Yk1PkCWbRyyj?si=76be5fe311dd4394

[1] Warami translates as “hello/where are you from” in Dharug language.

[2] Where possible, I refer to people by their preferred specific regional cultural identity (Nation and/or Language Group). First Nations is used predominantly elsewhere to outline the diversity of Indigenous groups both within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and globally. Trends and preferences vary from person to person, accounting for the different uses throughout the article.

[3] In Aboriginal English, several common nouns in Standard Australian English shift to proper nouns. Examples of words that can be capitalized include Country, Elders, and Custodians (Australian Government 2023).

[4] The data presented within this article are drawn from my doctoral studies (Fienberg, 2019) and the Finding Solid Ground research project. Approval for both these projects was sought and granted by The University of Sydney Human Research and Ethics Council. I would like to acknowledge the support and guidance of Debbie Higgison and Neville Williams Boney who are co-investigators in the Finding Solid Ground project.

[5] This vignette was created to explain the rationale of reaching out and common questions raised by students and pre-service teachers. It is not a presentation of data collected in the field.

[6] Aboriginal is a preferred term in Australia and is distinctly different from Torres Strait Islander cultures.

[7] Phillips and Bunda (2018) define storying “as the act of making and remaking meaning through stories” (7).

[8] Holding space requires “a commitment to tune into young people’s renderings of their concerns and desires and to create room for them to assert themselves with authority and expertise” (Filipiak 2020, 453).

[9] Archie Roach passed away in 2022. Following cultural protocol, Archie Roach’s sons, Amos and Eban, have given permission for Archie’s name to be used after his passing.

[10] Many First Nations peoples use the word proud when stating their cultural affiliation to challenge the dominant discourse of cultural loss and assimilation, emphasising strength, survival, and links to their ancestors (Bracknell, 2019).

[11] Emma Donovan is a soul singer who is renowned for her collaborations with The Putbacks. Emma was a mentor for the Solid Ground Program (2019–2020) and this article features extracts from a research topic yarn held in December 2021.

[12] The Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA) Awards are the Australian equivalent of the American Recording Academy Grammy Awards.

[13] In Aboriginal culture, Elders are addressed as Aunty and Uncle as a term of respect.

[14] Blak without the “c” is an Aboriginal English word used as an empowering descriptor for self-identity (Henningham 2021). The term Blak has been used by Indigenous artist-activists and community members to “reclaim historical, representational, symbolical, stereotypical, and romanticised notions of blackness” (Hazel 2018, 59).

[15] Jessica Mauboy was a finalist in the fourth season of Australian Idol (based on the British reality program Pop Idol created by Simon Fuller). She continues to hold a prominent position in Australian popular culture. Mauboy has collaborated with American R&B artists, appeared in films and television series, and even represented Australia in the Eurovision Song Contest.

[16] NAIDOC (National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee) Week is an annual event in the first week of July celebrating and recognising the history, culture, and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

[17] A detailed discussion of ethical considerations can be found in my doctoral thesis (Fienberg 2019, 114–18).

[18] Pseudonyms have been used for the students who are quoted.

[19] Mob is an Aboriginal English word for First Nations peoples. In this context local mob refers to a specific regional cultural affiliation or community of First Nations peoples.

[20] Thelma Plum is a proud Gamilaraay woman from Delungra in rural New South Wales. She was the inaugural winner of the Triple J Unearthed National Indigenous Music Award. During her involvement in the Solid Ground program (Fienberg and Higgison 2022), Thelma was finalising the release of her ARIA award winning indie-pop album Better in Blak (2019) which she describes as “a story about culture, heritage, love, and pain” (Plum n.d.).

[21] Evie J Willie is a soul singer-songwriter working primarily in Sydney. In addition to her work as a professional musician, Evie completed training as a youth worker. Her involvement in the Solid Ground program is also profiled by Webb and Bracknell (2021).

[22] Fellas is an Aboriginal English word for people.

[23] Joe Geia is a singer-songwriter and Elder of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander music community. “Yil Lull” (1988) was written as a song of protest and remains incredibly influential to this day (Geia n.d.).

[24] For cultural reasons, the full name of the late Dr G Yunupingu is not published.

[25] Neville Williams Boney participated in a research topic yarn in May 2022.

[26] For Aboriginal peoples, songlines (also known as dreaming tracks) “connect sites of knowledge embodied in the features of the land. It is along these routes that people travelled to learn from Country” (Neale and Kelly 2020, 9).

[27] This map locates the regional cultural affiliations preferred by the artists: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1khOOxXvPxlfW0SORquuYfe9i0iAWRXBj/view?usp=sharing. These affiliations include language groups (e.g., Ananindilyakwa), Nations (e.g., Gamilaraay) and geographic regions (e.g., Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands). The marks on the map are intentionally blurred, as there is a current avoidance of showing boundaries to minimise unnecessary conflict between Nations (Brenda Thornley, personal correspondence). Further information on each of the artists not previously profiled in the article can be found below:

Baker Boy (Danzal Baker) is a proud Yolŋu dancer, rapper, and singer. His songs regularly fuse English and Yolŋu Matha languages. Baker Boy’s music has been widely celebrated through successive National Indigenous Music Awards (Baker Boy n.d.).

Robbie Miller is a blues and roots artist with connections to the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands in central Australia. In 2013, he won the Triple J Unearthed National Indigenous Music Award helping launch his career. He has since released two EPs and an album in 2019 (Miller n.d.).

Miiesha (Miiesha Young) is a strong Anangu/Torres Strait Islander woman whose debut album Nyaaringu (2020) received the 2020 ARIA for Best Soul/RnB Release. The album translates as “what happened” in Pitjantjatjara language and is interspersed with stories from her late Grandmother (Miiesha n.d.).

Dallas Woods is a Noongar rapper from the East-Kimberley region in Western Australia. Dallas regularly collaborates with Baker Boy and released his debut album in 2022 (Woods n.d.).

Alice Skye is a Wergaia/Wemba Wemba woman from rural Victoria. In 2019, Alice signed to Bad Apples Music, a label that prioritises and “centres Blak excellence” (Skye n.d.). Her debut indie-pop album was released in 2021.

Benny Walker is a proud Yorta Yorta man and blues and roots musician. He has released three albums and received multiple National Indigenous Music Awards nominations (Walker n.d.).

Mo’Ju’s album Native Tongue (2018) documents a “deep exploration of their Filipino and Wiradjuri roots” (Mo’Ju n.d.). Mo’Ju’s music regularly crosses and challenges genre boundaries.

Emily Wurramara grew up on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory and releases music in English and Anindilyakwa, her first language. Her debut album, Milyakburra (2018), was nominated for an ARIA award for best Blues and Roots album (Wurramara n.d.). [28] Streaming services are placing an increasing emphasis on profiling First Nations artists, including Spotify’s Blak Australia (Nicol n.d.) and Deadly Beats (Beetson n.d.). NB: Deadly is an Aboriginal English word for excellent or amazing.

[28] Streaming services are placing an increasing emphasis on profiling First Nations artists, including Spotify’s Blak Australia (Nicol n.d.) and Deadly Beats (Beetson n.d.). NB: Deadly is an Aboriginal English word for excellent or amazing.