HEIDI WESTERLUND

Sibelius Academy of the University of the Arts Helsinki, Finland

TUULIKKI LAES

University of the Arts Helsinki, Finland

GUADALUPE LÓPEZ-ÍÑIGUEZ

Sibelius Academy of the University of the Arts Helsinki, Finland

December 2025

Published in Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 24 (7): 57–89 [pdf]. https://doi.org/10.22176/act24.7.57

Abstract: In the face of the unequal effects of neoliberalism on politics, education, and culture globally, there is an urgent call for music educators to proactively address the collective concerns for sustainability. As the need for transformation grows louder, music education cannot advocate for more resources to unlock its transformative powers while maintaining a presumed political neutrality that reinforces neoliberal logic. To transform the field’s professional responsibility beyond self-promoting advocacy, we propose systems thinking as a framework to make sense of our world and its complex interconnections. We use three animated systems stories to demonstrate how music education may sustain unsustainability, and articulate how, by attending to the bigger picture of issues of sustainability, music educators as systems practitioners can reach beyond the narrow purposes of technical rationality and self-centered aims that preserve the status quo of the system towards a new social contract (UNESCO 2021) between disciplinary experts and society.

Keywords: Advocacy, music education, neoliberalism, professionalism, social contract, sustainability, systems thinking

The Era of Polycrises: Towards a New Social Contract

In the contemporary era of polycrises, characterized by extreme and increasing injustice and insecurity, the need to address grand societal challenges and wicked problems has been a global priority—until the developments of recent years (World Economic Forum 2023). Despite many years of fostering agreement through multilateral international accords and policies—such as the United Nations’ Agenda 2030, which underscores the significance of human rights, cultural inclusion, equitable access, social justice, and environmental stewardship (United Nations 2015), along with the promotion of culture (UNESCO 2005) and arts education (UNESCO 2024)—we are currently observing a phenomenon described as the great regression (Geiselberger 2017), manifested as “fatigue with democracy” (Appadurai 2017, 7), and a “denial—or a resolute, emphatic and pugnacious rejection” of cultural heterogeneity (Bauman 2017b, 17). A pronounced resurgence of ethnic, national, and religious distinctions, characterized by an us versus them mentality, is increasingly evident (Geiselberger 2017; see also Geuss 2005). This phenomenon is reflected in a return to territorial affiliations and ‘retrotopia’ (Bauman 2017a), the romanticization of a lost national history and the idealized notion of a cohesive community. Such dynamics have intensified societal polarization, both domestically and internationally—a trend further exacerbated by the rise of populism and authoritarian politics. Consequently, a growing segment of the population feels disinclined to adhere to civilized behavior, often evading accountability for their anonymous expressions of hatred, forming emotional alliances rooted in resentment, and uniting through a rejection of civilization in favor of an imagined version of Western civilization (Nachtwey 2017). Paradoxically, at this critical moment when societal upheavals shake the traditional assumptions and values of “disembedded expert systems” (Giddens 1990), the arts are expected to be “the magic bullet of social change” (Maggs and Robinson 2020, 5)—even as governmental resources for the arts decline globally.

The most recent UNESCO World Inequality Reports (2018a; 2022) acknowledge that global inequality is not entirely inevitable, but rather a political choice (UNESCO 2018b; see also Piketty 2022); these authors call for practitioners to engage in action encouraging collective concern for wider issues of sustainability, which has become the byword of our time. Indeed, due to climate change, gender inequalities, migration, geopolitical conflicts, and humane worries related to the increasing costs of living and unemployment, both Gen Z and Millennials have become increasingly active in drawing attention to issues faced at both local and international levels (Deloitte 2023). We witness in global policies an attempt to push forward a transition towards seeking new subcontexts of responsibility in the arts and arts education—a new social contract for education (UNESCO 2021): a call “to abandon pedagogical modes, lessons, and measurements that prioritize individualistic and competitive definitions of achievement” (147) in favor of viewing pedagogy as a collective, relational process that empowers individuals “to take strong value systems forward, and to transform their environments” (60). This call for a renewal has become a global imperative for educational ecosystems, including higher education, as all institutions are expected to set “values such as respect, empathy, equality, and solidarity” at the core of their mission and provide students “with greater awareness of their civic and environmental responsibilities” (UNESCO 2021, 60; see also Davids and Waghid 2021). The calls for change are also becoming louder in music education. As Helena Gaunt and colleagues (2021) write, music-making raises “multiple ethical and political issues … that clearly need to be addressed as matters of urgency alongside aesthetic and imaginative concerns” (4). In other words, it has become essential to understand societal concerns and artistic imagination as reciprocal rather than opposing values in music professions.

In this article, we argue that sustainability is the byword of our time, since it concerns the wider “conversation about what kind of world we collectively want to live in now and in the future” (Robinson 2004, 382). In global policies, such as the United Nations’ Agenda 2030 (United Nations 2015), sustainability usually refers to the three intertwined dimensions of environmental, economic, and social, and the challenges arising when their interlinked co-effect is “feeding into a multidimensional sustainability crises” (Blühdorn 2017, 42). As such, scholars recognize the term as problematic and even “exhausted,” raising both theoretical and practice-based questions, including in education: “What is to be sustained? What needs to change and how? Who decides what change or sustainability looks like? What are the implications for practice?” (Hunter et al. 2018, 16). While we envision music education as one of the potential drivers of sustainability in twenty-first-century societies, this potential requires an understanding of sustainability as involving both inherently political and cultural acts (Robinson 2004). While cultural sustainability is a subsequent addition to the definition, the transversal idea of culture as the “fourth pillar of sustainability” (UCLG 2004; UNESCO 2013, 2018b) particularly addresses how culture plays not a side role in actions that can support sustainable development, but can actively shape human-nature relationship and values, and in this way challenges the Western extractivist and economy-driven approaches towards a more relational understanding of sustainability (Hawkes 2001).

The socio-political themes and concerns related to sustainability in music education are not new per se: Concepts such as community music, socially engaged music making, participatory art, social art, artistic citizenship, and artistic activism increasingly gain ground in music education research. However, the transformed societal positioning of music professionals requires increased awareness of the bigger picture in the professional education of musicians and music educators, particularly by reaching beyond the technical rationality that defines and restricts professional interests and value systems (Schön 1983; see also Barrett and Westerlund 2024; Pozo et al. 2022). This new positioning surpasses a simplistic additive approach to change, while also self-reflexively recognizing the possible negative consequences of music education as a social endeavor. Importantly, this professional transition towards “a new social contract for education” (UNESCO 2021) and “a renaissance of ‘morality’ and ‘responsibility’ in late modernity” (Bauman and Donskis 2013, as cited in Westerlund 2019, 505) not only relates to the positive social powers of music (DeNora 2009) but also requires acknowledging the other side of the coin: how musical practices and music education organizations can silently and systemically boost unhealthy individualism and competitiveness in society and sustain negative and discriminative power relationships between individuals and different groups of people, as discussed in scholarship of racism or ableism, for instance. In other words, music education may also sustain unsustainability through its collective, naturalized activities. Although scholars recognize that music education may not always serve good purposes (e.g. Bowman 2009; Regelski 2016; Reimer 2009), the ability for individual educators themselves to combine their self-critical structural transformation with the emerging new social and societal demands requires the use of imagination, craft-skills, and systems thinking beyond the known world of music and the status quo of music education institutions—a reframing of professional thinking beyond musical repertoires, genre boundaries, techniques, curricula, and established organizational practices.

This article aligns with the MayDay Group’s (2024) Action Ideals, particularly regarding raising ecological consciousness in music education that “embrace opportunities for insight and innovation presented by encounters with multiple disciplines that question normative discursive paradigms” and acknowledges the networked and connected nature of social practices, demanding that “our collaborations must continuously examine regimes of truth and taken-for-granted practices.” We also support the Action Ideal for addressing music teaching and learning as “inherently political endeavors” (MayDay Group 2024) and a vision of education that fosters an ethic of care and social wellbeing. However, “in order to improve existing structures and influence institutional change” (MayDay Group 2024), we promote a more culturally and politically diverse and cross-disciplinary discussion beyond Americentrism in music education.

A Systems Approach to Professionalism in Music Education

As a starting point, we first adhere to the sociology of professionalism, in which the concept of professionalism refers to the relationship between disciplinary expertise, expert education, and the whole of society (Cribb and Gewirtz 2015). Professionalism is thus not only about technical (music) competences in relation to musical traditions and practices but also about seeing one’s “work in the context of broader debates about social and civic purposes” (Cribb and Gewirtz 2015, 71; see also Barrett and Westerlund 2024; Westerlund and Gaunt 2021). Since professionalism is produced and enacted in social interactions within social systems, eventually becoming institutionalized reality (Abbott 1988; Berger and Luckmann 1966; Luhmann 2012), a transformative and expanding music professionalism (Westerlund and Gaunt 2021) requires that music professionals engage in and encourage collective interactions and imaginative change agency. The sociological concept of professionalism therefore exceeds its everyday use in music education, in which the term can refer simply to good musical quality in one’s professional performance—in terms of technical proficiency and the ability to effectively solve musical problems—calling for a more reflexive and transformative practitioner approach. This conceptualization departs from the deprofessionalization trends, in which less technical proficiency suffices for social relevance (Bates 2016), as well as from the shift to informal pedagogies and participatory practices, where the teacher is no longer needed (Green 2002). Instead of creating more polarization, we would like to note Donald Schön’s (1983) analysis of professional knowledge and the importance of how teachers frame “problems” in music education in the first place: with the “emphasis on problem solving, we ignore problem setting, the process by which we define the decision to be made, the ends to be achieved, the means which may be chosen. In real-world practice, problems do not present themselves to the practitioner as givens” (40).

Second, to engage with the quest for a new social contract between educational experts and society, as urged by UNESCO (2021), we propose systems thinking (e.g., Biggs et al. 2021; Checkland and Poulter 2006; Ison 2017; Meadows 2009; Stroh 2015) as a heuristic framework and tool to make sense of the world as a whole. Systems thinking can be seen as an effort to see the bigger picture: how issues of sustainability “result from the confluence and interaction of multiple, mutually reinforcing social and ecological processes at multiple scales” (Biggs et al. 2021, 4), and require the recognition that these challenges are “inherently systemic and intertwined,” as well as how there is an “escalating urgency to address these challenges … in how social and natural systems are studied” (4). Instead of focusing only on interactions in pedagogical situations or transmitting known musical practice, there now exists a wider need for music education to see how these situations and practices relate to larger social and structural issues; in other words, “to focus on political relationships, where the whole determines the mode of action of the individual members” and in which “we are being in political relationships with other human beings … as well as non-human entities” (Kuperus 2023, 23). Systems thinking can support the development of a systems praxis (Ison 2017), in which the practitioners are able to make critical connections to the emerging new social and societal demands, beyond established musical principles, traditions, and institutionalized practices, as well as beyond a simple non-critical alignment with the zeitgeist, as is typical for advocacy discourses. Such a systems praxis is a morally informed music education praxis that could lead to “structural social change within the realm of these practices” (Westerlund and Partti 2018, 534, italics added).

While systems thinking can refer to multiple approaches within diverse disciplines (e.g., Ison 2017, 30–36), we suggest that systems thinking could provide a sense-making framework of principles and ideas, in this case specifically for analyzing how music education as a social system operates and how it could be meaningfully reconfigured to resonate with the goals of sustainable development. Within this framework, professionals in music education can understand social systems as organic wholes of subsidiary components, including subsystems (e.g. higher music education) with “their own justificatory discourses and mechanisms of autopoiesis” (Laszlo 1996, 10). Music education as a social system (or a subsystem), then, can be recognized through its autopoietic, self-supporting, and self-reproducing “configuration of structures and processes where the system’s purpose regulates its functions and makes them meaningful in a given social setting, defining its boundaries” (Väkevä, Westerlund and Ilmola-Sheppard 2017, 134). The structures and communicative processes of a social system also explain its constituent division of labor and define the boundaries of the professional tasks and responsibilities that experts pursue within the system (Abbott 1988). Systems thinkers therefore emphasize that in order for a social system to avoid stagnation and survive in the changing environment of late modernity, its communicative processes must incorporate “a political will to redefine the purpose” in relation to those ongoing changes (Väkevä, Westerlund and Ilmola-Sheppard 2017, 137). As Lauri Väkevä and colleagues (2017) argue, “music education should not only aim to fulfil its perceived purpose and to maintain itself, but also to co-evolve as a part of the society” (135). In other words, music education as a social system should be recognized as evolving in relation to other systems and the systems environment as a whole.

In this theoretical contribution, we argue that this evolving adaptation to the environment requires the ability to reframe problems in professional work in music education beyond typically considered boundaries of the musico-pedagogical systems. As Schön (1983) wrote about professional practice, “problem setting is a process in which, interactively, we name the things to which we will attend and frame the context in which we will attend to them … It is rather through the non-technical process of framing the problematic situation that we may organize and clarify both the ends to be achieved and the possible means of achieving them” (40–41, italics added).

To support our argument, we present animated systems stories meant to support our theoretical argument and catalyze expanding professionalism within the music education system(s). As David Stroh (2015) has written, thinking in terms of systems a) “motivates people to change because they discover their role in exacerbating the problems they want to solve”; b) “catalyzes collaboration because people learn how they collectively create the unsatisfying results they experience” (21); c) “focuses people to work on a few key coordinated changes over time to achieve system wide impacts that are significant and sustainable”; and d) “stimulates continuous learning which is an essential characteristic of any meaningful change in complex systems” (22, italics added). In this way, systems thinking can help music educators and students move between “realistic” stories of individual events and “understanding and redesigning the deeper system structures that give rise to these events” (Stroh 2015, 32; see also Laes 2023). The presented video animations (see Videos 1, 2, and 3 below) aim to illustrate the problem of too narrowly framing problems—the historically deeply-rooted problems in the conservatory-based music education system in particular— and are meant to be “devices … to organise a debate about ‘change to bring about improvement’” (Checkland and Poulter 2006, 18); they are heuristic aids for learning about problematizing the mental models of reality, rather than representations of reality (Checkland and Poulter 2006; Stroh 2015; see also Väkevä, Westerlund and Ilmola-Sheppard 2017; Westerlund and Karttunen 2025), and for creating systems reflexivity (Westerlund et al. 2021) that can support becoming systems practitioners (Ison 2017).

Understanding The Bigger Picture through Systems Thinking

In the fast-paced neoliberal regime, complex phenomena can become buzzwords with empty meanings. One manifestation of such loss of meaning occurs when educational fields and organizations, including universities, harness the word sustainability for greenwashing without taking genuine ecological action (Álvarez-García and Sureda-Negre 2023). Likewise, the word system has spread from the natural and social sciences into the global education discourse without necessarily signaling a self-reflexive shift in practice (Faul and Savage 2023). Indeed, music education has also quickly turned the question of sustainability towards its own longevity (such as how to retain the acquired resources) instead of seeking its (new) relevance within the changing social systems and ecological crises. Such a self-centered, ego-logical approach can be unreflexive and blind to the unsustainable consequences of its own institutionalized operations (Westerlund 2023).

Systems thinking makes it possible to shift the focus away from quick fixes, simple technical solutions, “best practice models to the best fit,” and towards complex interactions (Faul and Savage 2023, 10); from linear impact thinking to non-linear, complex transformation (e.g. Biggs et al. 2021); from static mental models to exploring feedback loops that could be changed (Stroh 2015; Väkevä, Westerlund and Ilmola-Sheppard 2022); and from insistence on past meanings to recognizing emergent properties between systems components and “the arising of novel and coherent structures, patterns and properties during the process of self-organization in complex systems” (Goldstein 1999, 49, cited in Faul and Savage 2023, 14). Moreover, rather than harnessing experts alone to solve complicated problems, systems thinking relies on a holistic approach that requires local engagement “sensitive to local differences and power relations” (Faul and Savage 2023, 10). It allows understanding and working “with a system and its context” (7). Whereas in technical systems that respond to well-defined technical problems “the underlying philosophy is to ‘do the thing right’” (9), human systems involve messier, less-structured problems, and their “underlying philosophy is to ‘do the right thing’” (10).

Systems thinking is an emerging theoretical approach in arts education (e.g. Barrett and Westerlund 2024; Broome et al. 2017; Hunter et al. 2018; López-Íñiguez and Westerlund 2023; Väkevä, Westerlund and Ilmola-Sheppard 2017, 2022; Westerlund 2023). For instance, Jeffrey L. Broome and colleagues (2017) adopt an ecological systems thinking approach (see also Barrett and Westerlund 2024), arguing that systems thinking provides “a paradigm shift in how we think about problems” in arts education (Broome et al. 2017, n.p., italics added). Resonating with Schön’s argument concerning the crucial role of problem framing, they write, “if education is rooted in ‘The Big Picture’ instead of in its reductive elements it will grant educators a better opportunity to prepare students to consider themselves as inseparable citizens in a diverse and globalizing society” (n.p.). For instance, Guadalupe López-Íñiguez and Heidi Westerlund (2023) adopt a systems thinking view on gifted children’s musical education in the conservatory-based music education system. They argue that the educational system needs to reposition itself as “a moral and political endeavor” that requires the recognition of the changing understanding of childhood and children’s rights in society (e.g. United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, UN General Assembly 1989) and “the reconciliation of the over century-old tension between cognitive/rational educational efficacy views and moral theories in arts education” (López-Íñiguez and Westerlund 2023, 118). Scholars have also used systems thinking as an organizational framework to explore how institutionalized music education systems can be transformed through increased awareness about the system’s boundaries. In Finland, for example, Väkevä, Westerlund and Ilmola-Sheppard (2017) use systems thinking to demonstrate how social innovations in collaboration with other professional sectors can fight against the organizational silo effect (Tett 2015) and the overly rigid boundaries of the social system in order to respond to emerging societal needs, namely the integration of immigrants. As they write, institutional silos are “the paradox of the modern age,” in which the autopoetic institution “blindly pursues its purpose and social reproduction, favouring some and excluding others” (130). While the purpose of the social system “regulates its functions and makes them meaningful in a given social setting through discourse” (419), the problem arises when the system does not recognize and react to the changes in its environment. Social innovations can expand the system’s boundaries and integrate new values in institutional music education.

Systems thinking does not, however, define music or education; rather, it pinpoints how habitual and structural elements operate in human actions and institutionalized practices in relation to the wider environment. This may provide new tools for grasping, on the one hand, the potential of music education to become “the magic bullet of social change” (Maggs and Robinson 2020, 5), and on the other hand, for understanding the necessity of self-critical transformation of professional practices and established arts institutions in a changing society. In other words, with systems thinking one can identify the relations between what everyday language calls simply practice, context, and society. For instance, Broome with colleagues (2017) argue that “arts education can be specifically structured to provide the necessary environment for fostering the kind of creative, interdisciplinary, and holistic approach to innovative problem solving that underscores systems thinking” (n.p.). According to them, arts education can encourage students to consider multiple perspectives and “issues within a larger system through the arts—be it classroom-wide, nation-wide, or global” (n.p.). By “refocusing on the big picture, considering big ideas and the larger systems at play, arts educators overtly encourage citizenship in a pluralistic and diverse society” (n.p.). Instead of order and linear continuity, this, however, requires that arts educators embrace the messiness of the human system and the ongoing and rapid changes in society—“the swampy lowlands” of professional practice where, paradoxically, according to Schön (1983), “the greatest human concerns are” located (42).

Such swampy lowlands and reframing of professional problems emerged, for instance, in Tuulikki Laes’ pedagogical project with higher music education performance students, which aimed to expand the eco-artistic imagination in music performance study programs by engaging students in a collaborative, transprofessional process with sustainability scientists (Laes et al. 2024). The experimental new framing, characterized by uncertainty and complexity, challenged both the musicians and scientists, who had to (re)form, (re)interpret, and (re)organize their disciplinary understandings of interaction and knowledge creation. For the participating music students, it stimulated a “radical change in the mental models” and “a transformative ‘(environ)mental change’ in the role of the arts in tackling global challenges” (n.p.). Embracing such complexity in music education requires “an understanding that recognizes professionalism as a dynamic and continuously changing relationship between the profession and its environment—the society” (Westerlund and López-Íñiguez 2024, 4). In other words, in this case, the boundaries of music professionalism and professional responsibilities were neither arbitrary nor determined, but engaged with broader debates about social and civic purposes, which required that both the higher music education teachers and their students cope with change, uncertainty in terms of artistic quality, tensions in the social process of the interaction, and reconciling conflicting expectations between the different actors of the shared activities and overall process.

On the Problem of Political Neutrality

As mentioned, one of the central tenets of systems thinking is that it does not limit the professional view or research analysis to individual systems in isolation; instead, it acknowledges the intricate interactions between various systems and the extensive non-linear and constitutive consequences that arise from these interactions in their systems environment. For instance, political systems and decision-making systems influence not only human social systems but also non-human and material ecological systems, which in turn can affect human health and biological systems, among other connections (Broome et al. 2017, n.p.). During the past decade, ecomusicologists have articulated the interweaving of music with natural and built environments, and how this complex interconnectedness is not politically neutral (e.g. Allen and Titon 2023). However, current directions in ecomusicology discuss cultural manifestations in specific musical contexts related to the eco-crisis discourse (e.g., Schippers and Grant 2016), typically not addressing education matters, especially when it comes to professional education of musicians and the conservatory tradition.

In contemporary scholarship musical practices are understood as social; however, it is less common to see connections made between practices and political change (see, however, Woodford 2018). The conservatory-based professional music education system, in particular, has long been based on the flawed ideal of political neutrality—the assumption that it must “lead students through a path of technical sophistication and the refinement of natural talent in relative isolation from the social world, where genius can find its way without being shunned by external influence” (Gaztambide-Fernández 2008, 253). Henry Giroux’s (1999) distinction between politicized and political education is useful in recognizing the naivety of such a view. According to Giroux (1999), in “politicized education” the political aims are hidden behind the experts and the presumed neutrality and objectivity of scientific discourse. For instance, Väkevä, Westerlund, and Ilmola-Sheppard (2022) show that while a belief in neutral free choice can be justified as an egalitarian principle in music education systems, it paradoxically operates as a discursive mechanism that hides the ways in which institutionalized music education may actively construe itself as an exclusionary practice. In other words, by leaning on students’ free choice the system can externalize so-called non-musical problems—stepping aside from the “struggles over how society is organised” (Cribb and Gewirtz 2015, 71). In this way, music education that assumes “neutrality” “not only fails to equip students with political agency, but also indoctrinates them into the status quo (e.g. Western music, patriarchal structures, and other social hierarchies)” (Laes, Treacy, and Westerlund 2024, 463).

Political neutrality in music education can therefore be seen as a “politicized stance,” an illusion and a myth that provides a “safe” haven for professionals to avoid engaging reflexively and responsibly with the complexity of issues of sustainability. According to systems thinkers this can, however, make the social system vulnerable. For instance, in his seminal book The Fifth Discipline—The Art & Practice of The Learning Organization, Peter Senge (2006) compares such a stagnating organization to the frog that does not recognize the increasing temperature after being put into a kettle and is cooked without noticing the difference. Hence, from a systems perspective, to remain relevant to society organizations that carry responsibility, music education also need to willingly engage with the political and pose questions such as: What could we do better in our local and global environments to contribute to our relationships with each other? How could I contribute so that culture truly becomes the “fourth pillar of sustainability,” both on local level (UCLG 2004) and internationally (UNESCO 2018a), in its fully interconnected sense?

We thus assert that music education is always-already intrinsically political, being inherently interconnected to its surrounding social systems (Biesta, Laes, and Westerlund 2025). Even music can be seen as similarly political: “rather than being locked into fixed modes of interaction, music and politics can come together in contingent, temporary alliances” (Garratt 2019, 5) “to embrace the more diverse and inclusive agenda of ecocentric ecojustice” (Allen and Titon 2023, online abstract). This understanding of “the political” of musical practices and music education extends beyond protest music, repertoire choices, and performance contexts to matters of relationships, care, and responsibility within the complex interconnections between systems. Acknowledging that music education is political, whether explicitly addressing a political agenda or not, shifts the perspective from siloed technical rationality and assumed neutrality to broader existential questions concerning “the very way in which society is instituted” (Mouffe 2005, 9) and our commitment to “existing together” (Biesta 2013, 113).

On the Problem of Self-Promoting Professional Advocacy

As indicated above, the use of narrow technical rationality in defining the purpose of music education systems can sustain unsustainability and even abusive power relations. In music research, issues of sustainability tend to be limited to the preservation of musical traditions (as heritage) (Martínez-Rodríguez et al. 2022), music as an environmental practice or metaphor (Shevock 2018) or the sustainability of educational programs (Schippers and Grant 2016), while the conservatory-based higher music education system largely constructs its understanding of professional responsibility through the longue durée of the autonomous metatheoretical side of aesthetics. For instance, in their study in Finland, Westerlund and Sari Karttunen (2025) discovered that socially engaged musicians with higher music education backgrounds must constantly justify their work among their colleagues. The study shows that colleagues view their work, which requires flexibility, improvisation, and social interaction, as less worthwhile than work in orchestras and other established contexts, even when one and the same person operates in multiple music making systems, including ones with the highest prestige. In this case, instead of “doing the right thing” (Broome et al. 2017), the purpose of the music system becomes discursively defined in terms of “things being done in the right way” musically, according to the predefined quality criteria, as understood by the highest level of experts, and in the right place and social space.

For decades philosophers proposing the theoretical aims of music education as aesthetic education advocated for making “hard boundaries” between musical and other values, such as group participation and cooperation, which they saw as weakening the real import of music education (Reimer 2009, 11). The purpose of a music education system was founded solely upon musical criteria related to the established oeuvre of musical works (see also critique in Pozo et al. 2022). One of the first systems thinkers, the American philosopher John Dewey (1916), criticized this divide between musical and non-musical values and interests when arguing that experience is not “a patchwork of independent interests” but is relational (254). Even knowledge in music acquires its meaning and expands its realms in the context of its (social and material) use (e.g., Haggis 2008). Although contemporary theorists and practitioner researchers have sought to diversify the curricula in professional education (e.g., by suggesting collaboration, improvisation, and multi-/ intercultural/ community engagements) to respond to the emerging new needs and uses of music, music education research and the conservatory-based professional education system tends to eschew socio-political complexity, holistic contextuality, and emerging change. Therefore, music educators still more commonly seek justification and purpose for their work in high quality performances within established institutional contexts. Despite the decolonial, intersectional feminist, and anti-capitalist critical research perspectives and new concepts in music education described above, the more philosophical, political, and structural issues of the ongoing “social turn” in the arts in general (Charney 2021) and the aesthetic articulations of “art as politics” (e.g., Rancière 2013), as well as the interconnected lenses of sustainability, have remained marginal in the wider practice of music education and professional education of musicians (Campbell et al. 2016). Even research on musicians’ employability has not suggested radical reflexive repositioning in higher music education (e.g. López-Íñiguez and Bennett 2020), which in the other art fields has long been argued to “traverse the fields, the structures, the institutions” (Raunig 2007, 11).

Advocacy texts, in which the activities and doings of the systems in society fall to the side of technical rationality, to use Schön’s terms, reveal the narrower view of the purpose of the music education system(s), in which the linear causal framing of music’s impact on individuals is fitted within the neoliberal educational and social trends. For instance, the International Society for Music Education (ISME 2024) has published “research-based” advocacy materials for its international member audience, such as Keep Music Education Strong (NAMM and MENC 2016), according to which music in schools “develops skills needed by the 21st century workforce” and “helps students perform well in other academic subjects like math, science, and reading” (n.p.). The brochure makes rough generalizations between music and academic achievement, for example by stating that “Music majors are the most likely group of college grads to be admitted to medical school” (n.p.). This type of self-promoting advocacy neglects, for instance, the distortion of research results into “neuromyths” that have become normalized in music education’s professional discourse, “as they seem to effectively advocate the benefits of music and music education for the wider public” without requiring any change from music education itself (Odendaal, Levänen, and Westerlund 2019, 5). This kind of advocacy easily fabricates the image that every child has the potential to develop genius through musical learning, which effectively reproduces neoliberal economically oriented narratives about society and sustains the system’s own self-understanding, which reduces music education to an effective means of advancing one’s career. In other words, such an advocacy does not engage with necessary change—either in society or in its own operations—and sustains elitism, if not even the myth of musical genius.

Examples again abound in conservatory-based music education system. By advocating for talent development in music that insists “on always knowing what a child’s best interest is,” one is unable to accept and offer “multiple paths of being a student gifted for music, impl[ying] a failure of epistemic empathy and a lack of relational expertise” (López-Íñiguez and Westerlund 2023, 122). Such advocacy can in fact diminish the overall health, wellbeing, and well-rounded development of the child. A systems view on this scenario would require, then, recognizing professional work in music not only as a question of advocacy for the known criteria of the desired quality of musical outcomes. Furthermore, rather than perpetuating the binary opposites of gifted/non-gifted, or young/old that treat older adults as passive receivers of musical care over political agency, systems thinking can offer a new sustainable vision for more heterogeneous and intergenerational framings for music education (Laes 2023).

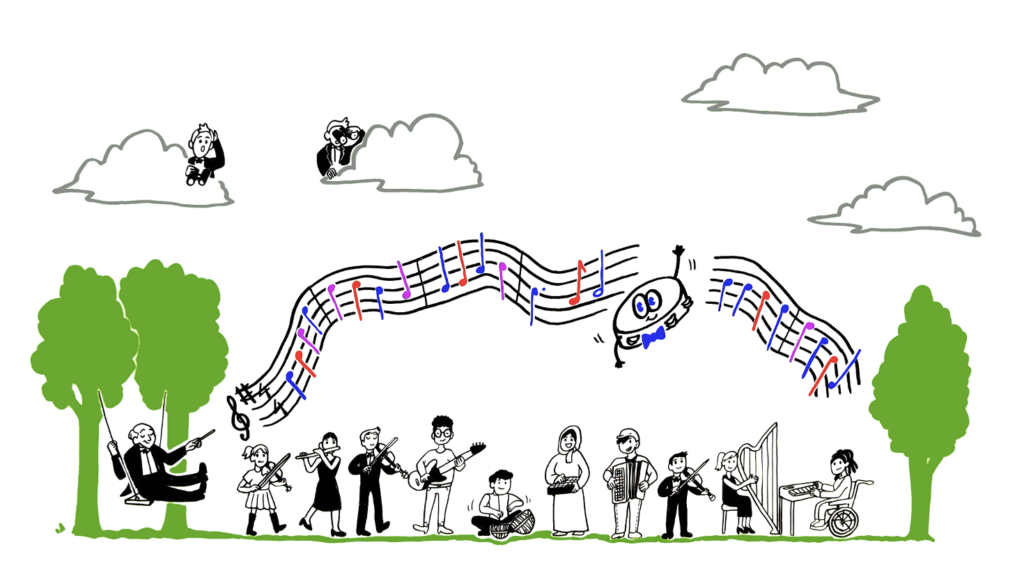

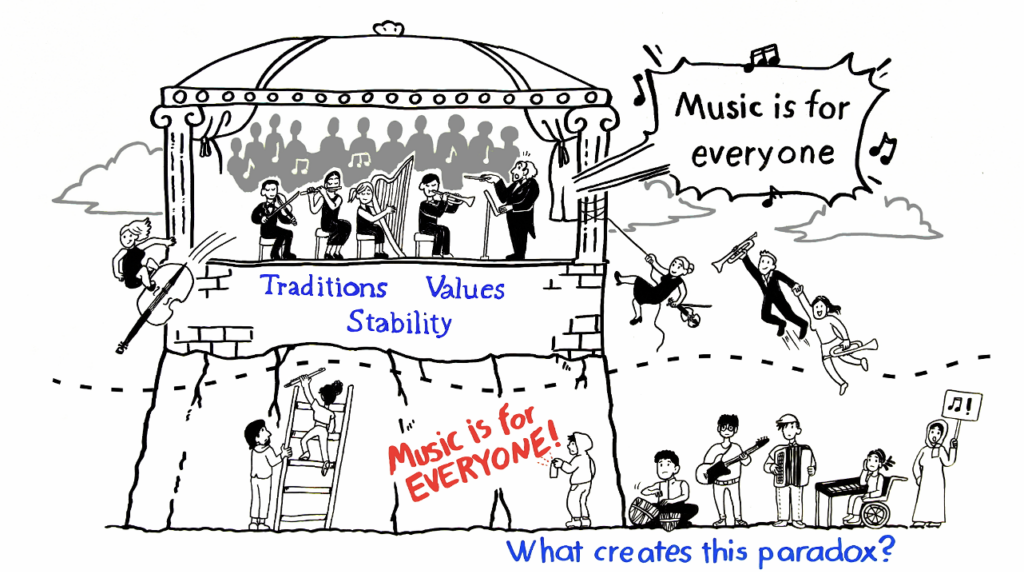

Hence, while advocacy texts in music education state that music is for everyone, in reality, through these texts the music education system easily reproduces and strengthens what Giroux (1999) called “politicized education”: the self-promoting political aim to preserve the status quo hidden behind the presumed neutrality and objectivity of scientific discourse. We ask: What creates this paradox in the music education system? (see Video 1).

| “Challenges of Music Education” |

CLICK HERE TO WATCH: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BJY6T7Y_rKM Video 1 transcription. Let’s take a critical look at the music education system. Isn’t it acting as if it’s an exclusive universe, where institutions define what quality and expertise mean. The system tends to focus on preserving traditions, values, and stability – and that emphasis on reproduction excludes certain people, some practices, new locations, and more imaginative uses of music. At the same time, the system preaches that music is for everyone while research shows that many remain excluded from it. What creates this paradox? Well, when the music education system stubbornly concentrates on sustaining its status quo, it overlooks how to engage with societal challenges in responsible ways. It doesn’t recognise how people could transform the system itself. Without challenging this paradox, music education will lose its opportunities to resonate with the people of our changing world. Video 1: Challenges of music education.[1] On the Problem of “Loving Music till it Hurts”

CLICK HERE TO WATCH: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BJY6T7Y_rKM Video 1 transcription. Let’s take a critical look at the music education system. Isn’t it acting as if it’s an exclusive universe, where institutions define what quality and expertise mean. The system tends to focus on preserving traditions, values, and stability – and that emphasis on reproduction excludes certain people, some practices, new locations, and more imaginative uses of music. At the same time, the system preaches that music is for everyone while research shows that many remain excluded from it. What creates this paradox? Well, when the music education system stubbornly concentrates on sustaining its status quo, it overlooks how to engage with societal challenges in responsible ways. It doesn’t recognise how people could transform the system itself. Without challenging this paradox, music education will lose its opportunities to resonate with the people of our changing world. Video 1: Challenges of music education.[1] On the Problem of “Loving Music till it Hurts”

The main problem associated with the neoliberal effect derived from the post-industrial model of progress and performativity is that it frames systems problems merely as individual defects. As James Garratt (2019) observes, “The ‘smart power’ of the neoliberal regime works through ‘the freedom of Can’ rather than the coercion of should, instilling dependency on its values and reward systems; as a result, individuals blame failure on their own inadequacies rather than on the defects of the system” (60–61). In music education, Westerlund (2019), referring to Zygmunt Bauman’s quest for a renaissance of morality and responsibility, points out how the “‘loving to do what one does well’—or what Bauman (2017a) calls “‘I can, and therefore I shall and will’ self-centred rationality” (Westerlund 2019, 25)—has framed music teachers’ mental models, significantly limiting the theoretical power and practical potential of the field. There is of course not anything wrong with focusing on motivational aspects in pedagogical situations, however when music educators combine this rationality with a belief in free choice the need to assign any responsibility for those excluded from the system remains unrealized. Rather, such exclusions become naturalized. Väkevä, Westerlund and Ilmola-Sheppard (2022) further connect the belief in individual free choice to the claimed elitism in established music education systems. According to them: “underpinning the free choice argument is the modern liberal notion of an autonomous human being free from certain forms of interference and forces of socialisation. When paired with this argument, elitism can be understood as a power structure that justifies music education as if it would be accessible to all on an equal basis” (418, italics original).

Within the American educational landscape, Robert Putnam’s Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis (2005) discusses the issues experienced by “the other half lives” of the society (263), warning about the perils of the continuing growth of inequalities. He asks, “[do] youth today coming from different social and economic backgrounds in fact have roughly equal life chances, and has that changed in recent years decades?” (31–32). The answer is no, but it is a complex no with far-reaching consequences. The reasons for inequality growth are compounded, including “globalization, technological change and the consequent increase in ‘returns to education,’ de-unionization, superstar compensation, changing social norms” (35–36).

While some countries try to respond to this situation in educational systems, the general framing of problems in education, including music education, is changing according to the neoliberal learning trend that the Dutch educational theorist Gert Biesta (2017b) terms “learnification.” Learnification moves away from educational questions of “content, purpose, and relationships” (28) to another extreme: it reduces the questions of education to questions of predefined learning outcomes, shifting the focus of teaching from the meanings and existential horizons of education to the question of “what education produces” (54). Paradoxically, the trend of learnification also poses a simplistic critique of the authoritarian role of the teacher and adopts a narrow functionalist and instrumentalist view of learning, evidenced in the tendency to think that anyone can teach in school without special expertise in education. As hyperindividualism penetrates the fields of education, parents increasingly expect students to take sole responsibility for their learning, competitiveness, and competence (see Pozo et al. 2022). Simultaneously, teachers are being pushed into the background as a threat to the ‘freedom’ of learners. As Randal Allsup and Westerlund (2012) described over a decade ago: “We are now encountering an unusual situation. Despite the attention surrounding learning environments and student outcomes, the teacher’s place within this order has become increasingly unstable. She is too mechanical, too free, defined by others, untrusted with choice, or paralyzed with excessive choice. Further unusual, there is a kind of silence surrounding the teacher as an agent, as one who theorizes” (124).

In music education, learnification manifests, for example, in recent tendencies to designate music teachers simply as facilitators and in the use of standards-based, sequential approaches, and methods to music learning (Laes, Treacy, and Westerlund 2024). By avoiding local and contextual complexity, learnification directs professionals to lean on technical rationality through centering technical skills, such as playing the right notes correctly, over the human problems of what is the right thing a musician can do in, and for, an individual, community, and society.

In the conservatory-based music education system, learnification strengthens the tying of learning outcomes to historically rooted layers of discursive meanings concerning musical excellence in performance, which have very little to do with contemporary societal problems. In this context, technical rationality is strengthened through the idea of absolute stylistic authenticity, which positions learners as servants of predefined musical and music education systems. The system’s narrow operations have been described by the expert gaze, which is embodied in the vertical and hierarchical career-oriented linear model of the study path towards musical excellence comprising the raison d’être of the entire field and explaining “why we do what we do—and why we do not do other things” (Westerlund and Odendaal 2025, 26). As Schön (1983) explains, “problem setting has no place in a body of professional knowledge concerned exclusively with problem solving. The task of choosing among competing paradigms of practice is not amenable to professional expertise” (19).

This initially modernist trend, positioned within the neoliberal effectivity frame concerning musical pasts, can be identified through ethnomusicologist William Cheng’s (2019) provocation on how people love music almost as if it is a living, conscious being and often so much that “it hurts.” He asks, “is it possible for our love and protection of music to go too far? Can such devotion ever do more harm than good? Can our intense allegiances to music distract, release, or hinder us from attending to matters of social justice?” (2).

If we love music so much that we even ascribe human features to it, in the same way as we ascribe human features to animals and other things we love, following Cheng we might ask: Do we love people as much as we love music? Does a musical work have dignity, and does it have rights? And, what about musicians’ and music students’ pain, dignity, and rights? Could music education be above all an existential matter instead of simply about learning?

If we take the example of children gifted for music described above, these young individuals stand out as exceptions in the conservatoire system, since they typically land in professional education at a very young age. They progress extremely fast, often within the most narrow (vertical) educational paths that disregard valuing radical differences and alternative visions; teachers nurture these children under the prophecy of a “musical miracle”. It is globally known, however, that the education of musically gifted children too often fails the children themselves, as they need to serve the system beyond their own life dreams. Research shows how, in the course of their education, the music can win out against the children’s humanity (López-Íñiguez and Westerlund 2023).

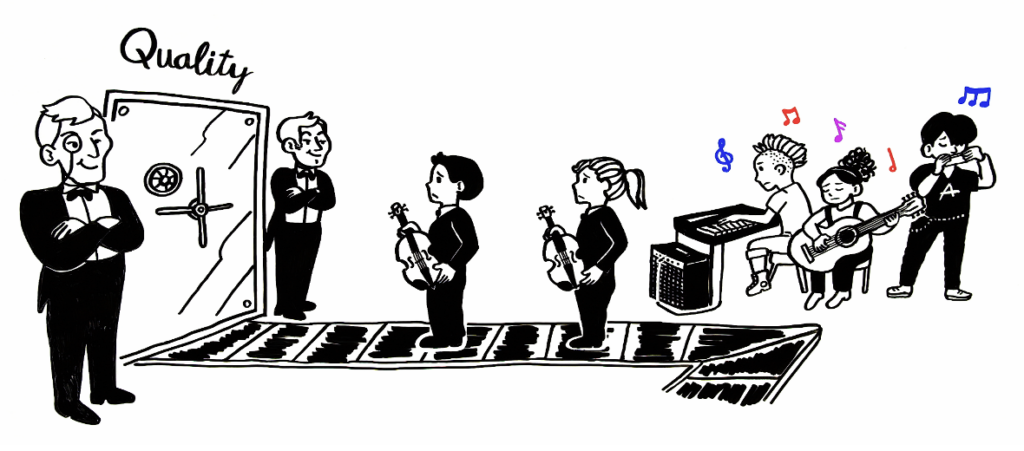

Today, music conservatoires in many countries embrace a wider plurality of musical genres in their educational programs that extends beyond Western classical music (e.g. Lawson, Salazar, and Perkins 2025); yet, the single-minded love for musical excellence as the one and only criterion for excellence may effectively overshadow the multiple ways this educational system could take into account the problems of contemporary society and prepare its students to face both the positive and negative trends in society. To transform the imbalance between the love of music and the love of people, the conservatoire system (still operating within performance-oriented higher music education) could resist the temptation to seduce gifted children into professional roles meant for adults and give up seeking institutional glory or legitimacy for teachers’ success through gifted children’s extraordinary performances. Following Cheng’s (2019) provocation, we can ask: Might a societal position towards wider sustainability require that the love for people prevails over the passionate love of music? By the same token, we can also ask: Will musically gifted children ever really thrive without conservatoires genuinely engaging with the institutional politics of care and responsibility? Could the music education system work harder on different dimensions of care ethics and consider moral values, solidarity, and empathy as fundamental dimensions of educational processes, as suggested in the UNESCO (2021) call for a new social contract for education? (see Video 2).

“Music education: preserving the past at future’s expense?”

CLICK HERE TO WATCH: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DcfgKQkHHYc Video 2 transcription. In the conservatoire system, quality is safeguarded by experts in a competitive setup. Children and young people are expected to conform to preserving the system instead of exploring musical possibilities in personally and socially resonant ways. Does the system serve children or are children serving the system? The narrow notions of music and quality do not fully take into account music’s societal possibilities. What if the conservatoire system were more caring? Could it offer diverse pathways for children and young people without jeopardizing their opportunities to become professionals? Imagine a music education system that valued more radical differences! |

Video 2: Music education: Preserving the past at future’s expense? Unlocking the Powers of Music Education?

Already decades ago, Christopher Small (1998) pointed out how music involves not simply abstract principles or sounds to be learned, but a fundamentally social and existential endeavor that structures our relationships with each other—musicking. In musicking, to use Small’s ecological term, we create “the public image of our most inwardly desired relationships: not just ‘showing [how these relationships] might be but bringing them into existence for the duration of the performance” (Small 1987, 70). From such a relational and ecological perspective, neither achieving learning outcomes nor the self-centered and individualistic “‘loving to do what one does well’ rationality” (Westerlund 2019, 25) can reveal the meanings that musicking seems to bring to people’s lives. One can ask, how could the music education system redefine its purpose beyond learning by referring to such desired relationships, especially in this era when societies are increasingly polarized? How could the emerging complexity in society be demonstrated in and through musicking beyond the existing musical traditions? Such a transition to a systems view seems necessary for music education to transcend its existence as an isolated sector of activity unto itself and evolve into an imaginative experimental endeavor that can become a transformative power as the fourth pillar of sustainability. Sustainability, even as the twenty-first century buzzword par excellence, does not offer direct solutions, but rather underscores the pressing issues and urgency of multidimensional and multilevel responsible action. As such, it can aid us to (re)think musical practices in terms of interconnected systems embedded within their wider environments (see empirical analysis, e.g., in Westerlund and López-Íñiguez 2024; Westerlund et al. 2025), to acknowledge our own professional role in systemically influencing the systems within which we work—and also the possibility for any music educator to become a systems practitioner (see Ison 2017)—and to find at least one scale on which to resist the great regression.

Moreover, returning to what Moira Faul and Laura Savage (2023) recognize, “although the word ‘system’ is increasingly used, systems thinking is not” (224). Indeed, music educators rarely use the word for transformational purposes or referring to change. Rather, a system refers to technical definitions, such as system of scales, assessment system, or Orff system. Instead, the more recent, emerging systems theorization in music education engages with the complex macro-level interactions and societal trends seeking to expand the view of professional responsibility in music education. Such expanding professionalism (Westerlund and Gaunt 2021) moves from the ego-logical ‘expert gaze’ to eco-logical concerns (Barrett and Westerlund 2024) and calls for change that would allow teachers to see music education not as an isolated sector but potentially an intersecting component of the fourth pillar of sustainability. In this inquiry we argued that in order for music education to engage with both contemporary society’s problems and what UNESCO (2021) calls a new social contract for education, the music education system needs to reframe professional problems beyond musical problems, predefined learning paths, and known musical excellence. Following philosopher Gerard Kuperus (2023), we urge music educators to collectively rethink who we are and how music education affects how we live together “in order to save the planet as a place where children not yet born can thrive. It is a gift to the future” (190).

The question then becomes, can music education, as a profession, resist an assumedly politically neutral—yet in fact politicized and economically-driven—framing of professional problems and advocacy, where measures of efficiency, competition, and profit override the ethics of our actions; where extreme individualism and “ecological blindness” kill care, empathy, and solidarity; and where aiming for probabilities instead of possibilities (Appadurai 2012) creates a tension in the educators’ ethico-political responsibility and moral imagination. A salient example of such an ostensibly neutral politicized framework is the overemphasis on art subjects as servants to STEM subjects, as previously discussed. This instrumentalist view places music educators in a challenging position where, as Biesta (2017a) argues, “it is not art that matters, but what art can produce or bring about” (37). Such advocacy is becoming increasingly common, framing music primarily as a tool for cognitive development and a driver of efficiency within neoliberal agendas – further reinforcing the very forces that reduce art to measurable outcomes rather than recognizing its capacity to bring meaning to life. When music education and arts subjects start competing with STEM subjects in schooling, it may be detrimental for music educators themselves to discursively position themselves as servants for the more valued subjects that are considered necessary for economically prosperous life paths. Music education may become blind not only in terms of the meanings of music making but also in how its own operations are interconnected with the more general values and moral concerns related to society—and therefore may risk its own integrity.

With the systems view proposed here we do not suggest that music education should abandon musical criteria or that it could solve the complex issues of sustainability; rather, we consider it necessary that music education starts engaging with the world and the political beyond its former tight disciplinary boundaries to seek an understanding of the bigger picture that expands beyond technical rationality and self-centered concerns. Music educators can become systems thinkers and systems practitioners who are able to reframe professional problems in relation to their specific contexts and contemporary environments, moving beyond past-oriented historically grounded repertoires towards integrating multiple values and criteria for excellence. They can ask “different and better questions and to see problems where no one is seeing them yet” (Biesta, Laes, and Westerlund 2025, 136). They might responsibly ask: What is “our gift to the future” (Kuperus 2023, 190)? What is “the world asking of me, … trying to say to me, … trying to teach me” (Biesta 2017a, 118)? What if systems thinking could unlock the powers of music education within its constantly changing and increasingly complex ecosystems (see Video 3)?

| “Music Education: Not Just a Side Character” |

CLICK HERE TO WATCH: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kokiiWjmJRQ

Video 3 transcription. I, the music education system, frequently find myself in the background. I am neglected, in comparison to other ‘more important’ disciplines. I’m expected to serve academic development in order to get more resources. But, as much as people claim that studying music helps improve math skills, I haven’t heard, ‘practice math to become better at music’! It is time to rethink and change! I can be so much more. I can bravely tackle broader societal and ecological challenges. I can play a vital role in transforming social, cultural, and political landscapes. I’m not just a side character. I am connected with society. I am not a gatekeeper, but an imaginative, responsible agent who loves people, as well as music. I must unlock my powers! Video 3: Music education: Not just a side character.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the following projects, funded by the Research Council of Finland: Music Education, Professionalism, and Eco-Politics (EcoPolitics) [grant number 338952]; Performing the Political: Public Pedagogy in Higher Music Education [grant number: 355247]; The Politics of Care in the Professional Education of Children Gifted for Music [grant number: 348591]; and Transition Pathways Towards Gender Inclusion in the Changing Musical Landscapes of Nepal (AmplifyHer) [grant number: 358072].

About the Authors

Dr. Heidi Westerlund is a professor at the Sibelius Academy of the University of the Arts Helsinki, Finland since 2004, and Adjunct Professor in Monash University, Australia. Her research interests include higher arts education, music professionalism, cultural diversity, and democracy in music education. She is the co-author of “Music Education, Ecopolitical Professionalism and Public Pedagogy” (Springer 2024) and co-editor of “Collaborative Learning in Higher Music Education” (Ashgate 2013), “Music, Education, and Religion” (IUP 2019), “Visions for Intercultural Music Teacher Education” (Springer 2020), “The Politics of Diversity in Music Education” (Springer, 2021), “Expanding Professionalism in Music and Higher Music Education” (Routledge 2021), and “Music Schools in Changing Societies” (Routledge 2024). She has led several Research Council of Finland funded research projects.

Dr. Tuulikki Laes is a researcher at the University of the Arts Helsinki, Finland. She holds a doctoral degree in music education, and her research areas include policy, systems thinking, democracy, inclusion, activism, and social justice within higher music education and socially engaged music practices. She is co-chair of the ISME Commission for Policy: Culture, Education and Media, a member of the editorial board of the International Journal of Music Education, and editor-in-chief of the Finnish Journal of Music Education. Among numerous international publications, her most recent work includes a co-edited book with Gert Biesta and Heidi Westerlund, titled “The Transformative Politics of Music Education” (Routledge 2025). Currently, she is leading an Academy Research Fellowship project, “Performing the Political—Public Pedagogy in Higher Music Education” (2023–2027), funded by the Research Council of Finland.

Dr. Guadalupe López-Íñiguez is a Spanish musician and university researcher based at the Sibelius Academy of the University of the Arts Helsinki, Finland. She holds a PhD in the psychology of music education and a master’s degree in cello performance. Her research expertise includes constructivism and conceptual change, giftedness and talent, employability and careers, wellbeing, performance optimization, and theories of emotion and motivation. She is a member of the editorial boards of the International Journal of Music Education and Gifted Education International. Among numerous international publications, she is co-editor of “Learning and Teaching in the Music Studio—A Student-Centred Approach” (Springer 2022), “Research Perspectives on Music Education in Ibero-America” (Routledge 2025), and “Caring for Gifted and Talented Music Learners—Perspectives and Future Possibilities” (Oxford University Press, in press). She is currently leading the project “The Politics of Care in the Professional Education of Children Gifted for Music” (2022–2027), funded by the Research Council of Finland.

References

Abbott, Andrew. 1988. The system of professions. University of Chicago Press.

Allen, Aaron S., and Jeff Titon. 2023. Sounds, ecologies, musics. Oxford University Press.

Allsup, Randall, and Heidi Westerlund. 2012. Methods and situational ethics in music education. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 11 (1): 124–48. https://www.tc.columbia.edu/faculty/rea10/faculty-profile/files/pWesterlund-MethodsandSituationalEthics2012.pdf

Álvarez-García, Olaya, and Jaume Sureda-Negre. 2023. Greenwashing and education: An evidence-based approach. The Journal of Environmental Education 54 (4): 265–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2023.2238190

Appadurai, Arjun. 2017. Democracy fatigue. In The great regression, edited by Heinrich Geiselberger, 1–9. Polity.

Appadurai, Arjun. 2012. The spirit of calculation The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 30 (1): 3–17.

Barrett, Margaret, and Heidi Westerlund. 2024. Music education, ecopolitical professionalism and public pedagogy: Towards systems transformation. SpringerBriefs in Education.

Bates, Vincent. 2016. Toward a sociology of music curriculum integration. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 15 (3): 8–20. act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Bates15_3.pdf

Bauman, Zygmunt. 2017a. Retrotopia. Polity.

Bauman, Zygmunt. 2017b. Symptoms in search of an object and a name. In The great regression, edited by Heinrich Geiselberger, 13–25. Polity.

Bauman, Zygmunt, and Leonidas Donskis. 2013. Moral blindness. The loss of sensitivity in liquid modernity. Polity.

Berger, Peter L., and Thomas Luckmann. 1966. The social construction of reality. Penguin Books

Biesta, Gert. 2013. The beautiful risk of education. Routledge.

Biesta, Gert. 2017a. Letting art teach. ArtEZ Press.

Biesta, Gert. 2017b. The rediscovery of teaching. Routledge.

Biesta, Gert, Tuulikki Laes, and Heidi Westerlund. 2025. A manifesto for transformative politics in music education. In The transformative politics of music education, edited by Tuulikki Laes, Gert Biesta, and Heidi Westerlund, 134–36. Routledge.

Biggs, Reinette, Clements, Hayley, de Vos, Alta, Folke, Carl, Manyani, Amanda, Maciejewski, Kristine, Martín-López, Berta, Preiser, Rika, Selomane, Odirilwe, and Schlüteret, Maja. 2021. What are social-ecological systems and social-ecological systems research? In The Routledge handbook of research methods for social-ecological systems, edited by Renate Biggs, Alta de Vos, Hayley Clements, Kristine Maciejewski, and Maja Schlüter, 3–26. Routledge.

Blühdorn, Ingolfur. 2017. Post-capitalism, post-growth, post-consumerism? Eco-political hopes beyond sustainability. Global Discourse (7) 1: 42–61.

Bowman, Wayne, D. 2009. No one true way: Music education without redemptive truth. In Music education for changing times. Guiding visions for practice, edited by Thomas A. Regelski and Terry J. Gates, 3–16. Springer.

Broome, Jeffrey L., Victoria Eudy, Yuha Jung, Ann R. Lovel, Julia Marshal, Cathy Smilan, Vanada, Delane I., and Pat Villeneuve. 2017. Essays on systems thinking: Applications for art education. The Journal of Art for Life 9 (3): 1–29. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323839941_Essays_on_Systems_Thinking_Applications_for_Art_Education

Campbell, Patricia Shehan, David Myers, and Ed Sarath. 2016. Transforming music study from its foundations: A manifesto for progressive change in the undergraduate preparation of music majors. https://www.music.org/pdf/pubs/tfumm/TFUMM.pdf

Charney, Kim. 2021. Socio-political aesthetics. Art, crisis and neoliberalism. Bloomsbury Academic.

Checkland, Peter, and John Poulter. 2006. Learning for action. A short definitive account of soft systems methodology and its use for practitioners, teachers and students. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Cheng, William. 2019. Loving music till it hurts. Oxford University Press.

Cribb, Alan, and Sharon Gewirtz. 2015. Professionalism. Polity.

Davids, Nuraan, and Yusef Waghid. 2021. Academic activism in higher education. A living philosophy for social justice. Springer.

Deloitte. 2023. Deloitte Global 2023 Gen Z and Millennial Survey. Deloitte. https://www2.deloitte.com/cn/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/genzmillennialsurvey-2023.html

DeNora, Tia. 2009. Music in everyday life. Cambridge University Press.

Dewey, John. 1916. Democracy and education. In The middle works of John Dewey 1899-1924, 9, edited by Jo Ann Boydston, 1–370. Southern Illinois University Press.

Faul, Moira V., and Laura Savage. 2023. Introduction to systems thinking in international education and development. In Systems thinking in international education and development. Unlocking learning for all?, edited by Moira V. Faul, 1–25. Elgar Publishing.

Garratt, James. 2019. Music and politics. A critical introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Gaunt, Helena, Celia Duffy, Ana Coric, Isabel R. González-Delgado, Linda Messas, Oleksandr Pryimenko, and Henrik Sveidahl. 2021. Musicians as “makers in society”: A conceptual foundation for contemporary professional higher music education. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 713648. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713648

Gaztambide-Fernández, Rubén A. 2008. The artist in society: Understandings, expectations, and curriculum implications. Curriculum Inquiry 38 (3): 233–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25475906

Geiselberger, Heinrich. 2017. Preface. In The great regression, edited by Heinrich Geiselberger, x–xvi. Polity.

Geuss, Raymond. 2005. Outside ethics. Princeton University Press.

Giddens, Anthony. 1990. The consequences of modernity. Polity.

Giroux, Henry. 1999. Impure acts: The practical politics of cultural studies. Routledge.

Goldstein, Jeffrey. 1999. Emergence as a construct: History and issues. Emergence 1 (1): 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327000em0101_4

Green, Lucy. 2002. How popular musicians learn: A way ahead for music education. Ashgate.

Haggis, Tamsin. 2008. Knowledge must be contextual: Some possible implications of complexity and dynamic systems theories for educational research. Educational Philosophy and Theory 40 (1): 158–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2007.00403.x

Hawkes, Jon. 2001. The fourth pillar of sustainability: Culture’s essential role in public planning. Cultural Development Network (Vic).

Hunter, Mary Ann, Aprill, Arnold, Hill, Allen, & Emery, Sherridan. 2018. Education, arts and sustainability: Emerging practice for a changing world. Springer Briefs for Education.

ISME 2024. Promoting music education. https://www.isme.org/music-education

Ison, Ray. 2017. Systems practice: How to act in situations of uncertainty and complexity in a climate-change world. 2nd ed. The Open University.

Kuperus, Gerard. 2023. Ecopolitics. Redefining the polis. State University of New York Press.

Laes, Tuulikki. 2023. Rethinking, re-storying, and reclaiming narratives of aging in music education. Action, Criticism and Theory for Music Education 22 (3): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.22176/act22.3.227

Laes, Tuulikki, Danielle Treacy, and Heidi Westerlund. 2024. Beyond “democracy”: Making space for the educational and political in school music. In The SAGE Handbook of School Music Education, edited by José Luis Aróstegui, Koji Matsunobu, Jeananne Nichols and Catharina Christophersen, 457–72. Sage.

Laes, Tuulikki, Heidi Westerlund, Danielle Treacy, and Katja Thomson. 2024. Towards the ‘swampy lowlands’ of professional practice: Higher music education teachers reflecting on arts-science integration in the Artists for a Sustainable Future course. Diskussion Musikpädagogik 102. https://www.junker-verlag.com/dmp-102

Laszlo, Ervin. 1996. The systems view of the world. A holistic vision for ourNtime. Hampton Press.

Lawson, Colin, Diana Salazar, and Rosi Perkins. 2025. Inside the contemporary conservatoire: Critical perspectives from the Royal College of Music. Routledge.

López-Íñiguez, Guadalupe, and Dawn D. Bennett. 2020. A lifespan perspective on multi-professional musicians: Does music education prepare classical musicians for their careers? Music Education Research 22 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2019.1703925

López-Íñiguez, Guadalupe, and Heidi Westerlund. 2023. The politics of care in the education of children gifted for music: A systems view. In Oxford handbook of care in music education, edited by Karin S. Hendricks, 115–29. Oxford University Press.

Luhmann, Niklas. 2012. Theory of society, vol. 1. Stanford University Press.

Maggs, David, and John B. Robinson. 2020. An introduction. In Sustainability in an imaginary world, edited by David Maggs and John B. Robinson, 3–12. Routledge.

Martínez-Rodríguez, Marta, José Manuel Hernández-de la Cruz, Borja Aso, and Carlos D. Ciriza. 2022. Musical heritage as a means of sustainable development: Perceptions in students studying for a degree in primary education. Sustainability 14 (10): 6138. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106138

MayDay Group. 2024. Action Ideals. https://maydaygroupofficial.wixsite.com/mayday-group/about

Meadows, Donella H. 2009. Thinking in systems: A primer. Earthscan.

Mouffe, Chantal. 2005. On the political. Verso.

Nachtwey, Oliver. 2017. Decivilization: On regressive tendencies in Western societies. In The Great Regression, edited by Heinrich Geiselberger, 130–42. Polity.

NAMM and MENC. 2016. Keep music education strong. https://www.nammfoundation.org/educator-resources/keep-music-education-strong

Odendaal, Albi, Sari Levänen, and Heidi Westerlund. 2019. Lost in translation? Neuroscientific research, advocacy, and the claimed transfer benefits of musical practice. Music Education Research 21 (1): 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2018.1484438

Piketty, Thomas. 2022. A brief history of inequality. Harvard University Press.

Pozo, Juan I., M. Puy Pérez-Echeverría, Guadalupe López-Íñiguez, and José A. Torrado. 2022. Learning and teaching in the music studio. A student-centred approach. Springer. Landscapes: the Arts, Aesthetics, and Education, vol 31. Springer.

Putnam, Robert D. 2015. Our kids: The American dream in crisis. Simon & Schuster.

Rancière, Jacques. 2013. The politics of aesthetics. Bloomsbury.

Raunig, Gerald. 2007. Art and revolution: Transversal activism in the long twentieth century. Semiotext.

Regelski, Thomas A. 2016. Music, music education, and institutional ideology: A praxial philosophy of music sociality. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 15 (2): 10–45. act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Regelski15_2.pdf

Reimer, Bennett. 2009. Seeking the significance of music education: Essays and reflections. National Association for Music Education. Rowman & Littlefield.

Robinson, John. 2004. Squaring the circle? Some thoughts on the idea of sustainable development. Ecological Economics 48: 369–84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2003.10.017

Schippers, Huib, and Catherine Grant. 2016. Sustainable futures for music cultures. Oxford University Press.

Schön, Donald A. 1983. The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Routledge.

Senge, Peter M. 2006. The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. 2nd ed. Doubleday.

Shevock, Daniel J. 2018. Eco-literate music pedagogy. Routledge.

Small, Christopher. 1987. Music of the common tongue: Survival and celebration in African American music. Wesleyan University Press.

Small, Christopher. 1998. Musicking: The meanings of performing and listening. Wesleyan University Press.

Stroh, David. 2015. Systems thinking for social change: A practical guide to solving complex problems, avoiding unintended consequences, and achieving lasting results. Chelsea Green.

Tett, Gillian. 2015. The silo effect. Why every organisation needs to disrupt itself to survive. Abacus.

UCLG, Committee on Culture. 2004. Agenda 21 for culture: An undertaking by cities and local governments for cultural development. United Cities and Local Governments.

UN General Assembly. 1989. Convention on the rights of the child. United Nations, Treaty Series 1577 (3): 1–164. https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/1990/09/19900902%2003-14%20AM/Ch_IV_11p.pdf

UNESCO. 2005. Convention on the promotion of the diversity of cultural expressions. https://www.unesco.org/creativity/en/2005-convention

UNESCO. 2013. The Hangzhou declaration: Placing culture at the heart of sustainable development policies. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000221238.locale=en

UNESCO. 2018a. Culture for the 2030 Agenda. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000264687

UNESCO. 2018b. World inequality report. Harvard University Press. https://wir2018.wid.world/

UNESCO. 2021. Reimagining our futures together: A new social contract for education. Report from the International Commission on the Futures of Education. https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/reimagining-our-futures-together-new-social-contract-education

UNESCO. 2022. World inequality report. Harvard University Press. https://wir2022.wid.world/

UNESCO. 2024. A framework for culture and arts education. https://www.unesco.org/en/wccae2024-framework-consultation

United Nations. 2015. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

Väkevä, Lauri, Heidi Westerlund, and Leena Ilmola-Sheppard. 2017. Social innovations in music education: Creating institutional resilience for increasing social justice. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 16 (3): 129–47. https://doi.org/10.22176/act16.3.129

Väkevä, Lauri, Heidi Westerlund, and Leena Ilmola-Sheppard. 2022. Hidden elitism: The meritocratic discourse of free choice in Finnish music education system. Music Education Research 24 (4): 417–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2022.2074384

Westerlund, Heidi. 2023. Kriisien ja epävarmuuksien ajan ekopoliittinen ammatillisuus musiikkikasvatuksessa. (Ecopolitical professionalism in music education in times of crises and insecurities). In Musiikkikasvatus Muutoksessa (Changing Music Education), edited by Heidi Partti and Marja-Leena Juntunen, 452–75. Sibelius Academy, University of the Arts Helsinki.

Westerlund, Heidi. 2019. The return of moral questions: Expanding social epistemology in music education. Music Education Research 21 (5): 503–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2019.1665006

Westerlund, Heidi, and Helena Gaunt, eds. 2021. Expanding professionalism in music and higher music education–A changing game. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003108337

Westerlund, Heidi, Sari Karttunen, Kai Lehikoinen, Tuulikki Laes, Lauri Väkevä, and Eeva Anttila. 2021. Expanding professional responsibility in arts education: Social innovations paving the way for systems reflexivity. International Journal of Education & the Arts 22 (8). http://doi.org/10.26209/ijea22n8

Westerlund, Heidi, and Sari Karttunen. 2025. Transforming higher music education: Systems learning through counter-stories of Finnish socially engaged musicians. In Turning Social. On the Social-Transformative Potential of Music Education, edited by Axel Petri-Preis and Annette Ziegenmeyer, 169–187. mdw Press.

Westerlund, Heidi, and Guadalupe López-Íñiguez. 2024. Contemporary composers’ changing “practice in context”—What can higher music education learn from Theodore Schatzki’s practice theory? Research Studies in Music Education 47 (2): 280–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X241249098

Westerlund, Heidi, and Heidi Partti. 2018. A cosmopolitan culture-bearer as activist: Striving for gender inclusion in Nepali music education. International Journal of Music Education 36 (4): 531–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761418771094

Westerlund, Heidi and Albi Odendaal. 2025. Expanding mental models in music education: Transformational praxis beyond the expert gaze. In The transformative politics of music education, edited by Tuulikki Laes, Gert Biesta, and Heidi Westerlund, 26–42. Routledge.

Westerlund, Heidi, Danielle Treacy, Katja Thomson, and Albi Odendaal. 2025. Music educators as imaginative “designers.” Emerging transformative ecopolitics in higher education. In The transformative politics of music education, edited by Tuulikki Laes, Gert Biesta, and Heidi Westerlund, 43–62. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003403036-4

Woodford, Paul, G. 2018. Music education in an age of virtuality and post-truth. Routledge.