ROGER MANTIE

University of Toronto Scarborough (Canada)

ALEX RUTHMANN

New York University Shanghai (China)

July 2025

Published in Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 24 (4): 1–24 [pdf]. https://doi.org/10.22176/act24.4.1

Ethics lies at the very heart of scientific endeavours and much of our work revolves around ethical considerations…

Senior faculty probably hold their current positions through their success in the game, which may or may not have been achieved by using the most ethical ways. (Chapman et al. 2019, 7)

The academic publishing landscape has experienced tremendous upheaval in the past couple of decades—everything from neoliberal, managerial logics in the academy that pressure academics to capitulate to algorithmically-determined “metrics” and “impact” to exploitative operators quick to cash in on faculty desperation for publication credits. And now, Generative AI and “paper mills” that have flooded journal submission systems with faux research and scholarship[1] (all of which has to be dealt with by volunteer editors and reviewers, placing an ever-greater burden on an already-overburdened system). As music education researchers, we may not be in a position to influence solutions to the broader damaging effects of neoliberalism or the existence of predatory journals. We can, however, seek to address what is within our sphere of influence in research and scholarship: our own ethical practices. To the best of our knowledge, this special issue of Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education is the first coordinated effort in music education to try to “surface motives” in our research and publishing practices. In this respect, we are quite a bit behind other fields. A smattering of titles from other disciplines illustrates: “A Systematic Review of Research on the Meaning, Ethics and Practices of Authorship across Scholarly Disciplines” (Marušić, Bošnjak, and Jerončić 2011), “The Rules and Realities of Authorship in Biomedical Journals: A Cautionary Tale for Aspiring Researchers” (Beshyah et al. 2018), “Publish, Perish, or Salami Slice? Authorship Ethics in an Emerging Field” (Pfleegor, Katz, and Bowers 2018), “Games Academics Play and Their Consequences: How Authorship, h-index and Journal Impact Factors are Shaping the Future of Academia” (Chapman et al. 2019).

In the vernacular of academia, research activity is knowledge creation; researchers (including practitioner-researchers) create “new knowledge.”[2] The knowledge in question here, however, is not lay or everyday knowledge like how to tie your shoes or knowing that a red stove element is hot. The “new” knowledge of the researcher is almost always formal, abstract, and/or theoretical knowledge—i.e., professionally accepted knowledge. Creating new knowledge raises immediate questions, however. What constitutes new knowledge? How does new knowledge come into being? One cannot simply proclaim to have created a new form of math knowledge where two plus two equals five, for example. In order for knowledge to become scientific/professional knowledge, it needs to be recognized and accepted by more than one person or a small group of people. There is also a competence and authority aspect involved: even if one could convince a large number of lay people that there is a form of math where two plus two equals five, this knowledge would remain marginal and discredited unless and until it was recognized and accepted by the community of math experts.

The typical arbitration process of knowledge validation in the academic community is peer review. This is predicated, presumably, on the belief that the people best positioned to judge what does and does not constitute acceptable new knowledge are those with sufficient expertise to recognize it. A quick internet search reveals dozens of commentaries on the pros and cons of peer review, ranging from the critical (“Let’s Stop Pretending Peer Review Works”[3]) to the supportive (“Peer Review: The Worst Way to Judge Research, Except for All the Others”[4]). There are many criticisms of peer review listed by commentators, among them being that the process isn’t overly effective in screening and improving quality, in part due to the limited number of people competent to conduct the reviews (Kelly, Sadeghieh, and Adeli 2014).

Another common criticism of peer review is more epistemological than logistical. It holds that peer review is inherently conservative, thus limiting creativity. As Kelly, Sadeghieh, and Adeli (2014) write, peer review represses “scientists from pursuing innovative research ideas and bold research questions that have the potential to make major advances and paradigm shifts in the field, as they believe that this work will likely be rejected by their peers upon review” (28). The authors’ reference to paradigm shifts is an obvious allusion to Thomas Kuhn’s (1962) book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, where Kuhn explains how difficult it is for new knowledge paradigms (i.e., accepted truths) to emerge. Knowledge creation that questions or challenges doxa, Kuhn argues, is almost always rejected by those responsible for creating and upholding the status quo.

An issue not thoroughly addressed by Kuhn—one central to this special issue of ACT—is one of motive. It is one thing to critique the presumed conservatism of peer review in the face of some sort of quasi value-free pursuit of truth; it is quite another to place the conservatism of peer review in a competitive landscape where political values determine whose ideas are recognized, validated, and funded, and whose are silenced and forgotten. What does a researcher do if the status quo is considered unjust, for example? How does one go about challenging perceived hegemonic knowledge systems (what Michel Foucault might call “regimes of truth”)?

One of the early examples in the field of education expressing the value and potential of research as activism was Patricia Lather, whose 1991 book, Getting Smart: Feminist Research and Pedagogy Within/in the Postmodern, described four motives for research: predict, understand, emancipate, and deconstruct. At the time, the idea of emancipatory research was radical. Research in the positivist tradition was thought to be objective and value-free. Knowledge creation with overt, value-driven motives was not research, it was rhetoric or criticism. Despite the challenges of paradigm shifts through emancipatory research, the emergence of women’s studies, Black studies, and other marginalized areas previously absent from academia would appear to support the possibility, however difficult, for activist knowledge creation in the face of peer review’s inherent conservatism.

To the extent one believes that the knowledge and experiences of marginalized groups deserve to be recognized and validated by their presence in higher education, this is a good thing.[5] But what happens if and when the motives of researchers are not driven by altruism or benevolence? What if, for example, knowledge creation is driven by a profit motive—either directly, through research funded by entities that stand to gain financially from the publication of results that support their activities, or indirectly, by researchers who engage in paid activities beyond and outside of their academic roles. Examples of this range from funded contract work, to advancing pedagogies or creating materials as part of entrepreneurial “side gigs.” One is more likely to generate the necessary cachet for entrepreneurial activity if one publishes research that can be leveraged for paid opportunities.[6]

Funded research is less common in music education than it is in many other disciplines, but there is some funded research in our field. This inevitably introduces the potential for financial interests to influence researcher decisions (what to study, who to study, how to study, and so on). Even though some research funding comes from governmental bodies that believe in an arms-length approach, where researchers are free to conduct their work according to their own ethics and principles, funding from non-governmental entities and industry sponsorships sometimes comes with agendas where researchers are expected (implicitly or explicitly) to provide findings and results that support and advance the mission of the funder (see, e.g., Chapman et al. 2019). Although tempting to dismiss this as more of a problem in fields like medicine, where funded research on, say, pharmaceuticals has financial implications on a scale almost unimaginable in music education, the underlying ethical principles are the same: the motives of researchers matter.

The Changing Journal Publishing Landscape

Junk (spam) email has existed for many years. The frequency of solicitations targeting academics seems to have experienced a sharp uptick, however. What is concerning is not just the frequency but the content. Consider the following junk folder examples—all taken from one day (February 20, 2025):

Dear Prof. Mantie,

Hope this email finds you in good health and high spirits. In recognition of your well-respected work, you are cordially invited to submit a paper to journal /Arts & Communication/ (ISSN: 2972-4090)… We can give you full APC waiver to publish your article for this time. Just refer to my name Tracy in the cover letter and I will apply for APC waiver for you.Dear Dr. Mantie, Roger,

I hope this message finds you well. My name is Dorothy Xu, and I am honored to introduce you to our journal, Research on World Agricultural Economy (RWAE, ISSN / eISSN 2737-4777 / 2737-4785). RWAE is dedicated to publishing research related to agricultural policy and agricultural economics. Our journal is indexed in ESCI(Web of Science), Scopus, EBSCO, CABI, Google Scholar, CNKI Scholar, AgEcon Search, and RePEc, which ensures that your research will be visible to scholars, practitioners, and policymakers worldwide, increasing its visibility and impact.Respected Sir/Madam,

I hope this letter finds you well. I am writing to invite you to contribute an article for the upcoming issue of [International Journal of Teacher Education Research Studies (IJTERS) ISSN-3049-1614 (ONLINE)], which is scheduled for publication by 20th March 2025… Deadline for Submission: [5th March 2025]Dear Researcher,

SSRG – International Journal of Communication and Media Science (IJCMS) is a fully open access, international journal that aims to provide academia and industry with a venue for rapid publication of research manuscripts reporting innovative computational methods and applications to achieve a major breakthrough, practical improvements, and bold new research directions within a wide range of Computer applications…. Manuscript Submission Deadline: 20th Feb 2025. No doubt many readers regularly receive similar emails.

It is easy to just delete spam, of course, but the content and underlying motives of such solicitations are concerning. Given that the emails above mention journals such as Research on World Agricultural Economy and International Journal of Communication and Media Science, one presumes that these messages were simply sent to every academic email that the senders were able to harvest online in hopes that one might land. But what is one to make of a solicitation sent on February 20th that includes submission deadlines of February 20th and March 5th?

The emails above are suggestive of pay-to-publish predatory journals. Such journals have been around for at least 20 years. Lists of predatory journals can be found online, although it is becoming more difficult to distinguish predatory journals from legitimate ones. Frontiers, for example, has a pay-to-publish model but uses established academics as editors and reviewers. While one can still question the motives of journals like Frontiers, in that rejected manuscripts do not generate revenue—i.e., the profit motive may create an incentive for higher acceptance rates—the journal does follow conventional peer review practices (though as a single-blind rather than double-blind journal).

And then there is this example, found in the spam folder just a couple of days after the previous emails:

Dear Prof.Roger Mantie,

Hope this email finds you well. Considering your great achievements in the field, we believe that you would serve as an excellent reviewer of the manuscript “MCB-1596”, which has been submitted to our open-access journal/Molecular & Cellular Biomechanics/(MCB, ISSN: 1556–5300).

The idea of a music education professor being asked to be a reviewer for a journal titled Molecular & Cellular Biomechanics is seemingly preposterous—until one looks at the title and abstract included in the email:

“Score Recognition and Music Evaluation Based on CRNN-lite and pYin”

As a teaching method, music practice can provide students with more personalized teaching services. However, there are currently issues with the lack of score and inconsistent quality of sparring teachers in offline music practice. To solve these two problems and improve the quality of music practice, three improvements are made to convolutional recurrent neural networks. Therefore, a final lightweight score recognition method is constructed. In addition, the study also adopts probability yin-yang pairing algorithm and sequence dynamic time warping algorithm to design the final segmented music evaluation method. According to the results showed, on the original dataset, the maximum symbol error rate and sequence error rate of the score recognition model were 0.79% and 10.7%, respectively. The minimum and maximum time consumption of this model were 0.714s and 0.744s, respectively. The maximum recognition accuracy on diacritical marks and rest marks was 99.68% and 99.87%, respectively. On an incomplete dataset, the final effective rating of the segmented music evaluation method accounted for 83.57%, demonstrating good robustness. The designed model has good performance, which can provide technical support for music practice, providing higher quality teaching services for music learners.

We are left wondering what is most problematic in this scenario: the abstract, which may appear to be complete gibberish to a music education scholar, or that a music study was sent to a journal called Molecular & Cellular Biomechanics and that they would be open to publishing it (likely for a fee)—assuming it cleared the bar of rigorous peer review by sending it randomly to some faculty member with the word “music” in their faculty description.[7]

Companies are also emerging and developing partnerships with pay-to-publish and other academic journals to not only provide a stream of “pre-qualified” manuscripts, but to also offer reviewers, marketing and promotion benefits, as well as boosts to citation counts. Consider this recent email inquiry received by the editorial team of the International Journal of Music Education:

Respected Sir,

I hope you are doing well. I am Lin, Co-founder of Changzhou Houwen Technology.Co., Ltd. I am writing to let you know that I am interested in collaborating with your respected journal, to publish a series of high-quality academic papers. This partnership can be mutually beneficial, enhancing your journal’s reputation while providing our research team with a reliable platform for timely and impactful publication.

Our team comprises experienced researchers and scholars committed to producing innovative, evidence-based studies. We have a meticulously prepared pipeline of manuscripts that address significant gaps in the literature and align with the themes and scope of the International Journal of Music Education.

We are confident that our submissions will enrich your journal’s content, attract a wider readership, and enhance its academic standing. In return, we seek a partnership that ensures:

- Timely Publication: Adherence to predictable timelines for review and publication.

- Collaborative Discussion on Charges: We are open to discussing the publication charges based on your standard rates and exploring flexible options.

- Mutual Promotion: We will actively promote our publications and your journal through academic networks, social media, and conference presentations, thereby increasing the journal’s visibility and citations.

Our manuscripts undergo rigorous internal review processes, ensuring they meet high academic standards before submission. The topics we propose address contemporary challenges and advancements in all fields, aligning with the interests of your readership. By publishing cutting-edge research, the International Journal of Music Education can further establish itself as a leading platform in its domain.

We would be delighted to discuss this collaboration further. Please let us know your journal’s publication timelines and procedures, the standard rates for publication charges, any available discounts for bulk or ongoing submissions, and any specific requirements or preferences regarding the type of submissions you are currently prioritizing.

We are committed to fostering a long-term, mutually beneficial relationship with the International Journal of Music Education. Please let me know a convenient time for a call or meeting to discuss this collaboration in more detail. I am happy to provide further information about our research or answer any questions you may have.

Thank you for considering this proposal. I look forward to working together to advance academic excellence and the reputation of the International Journal of Music Education.

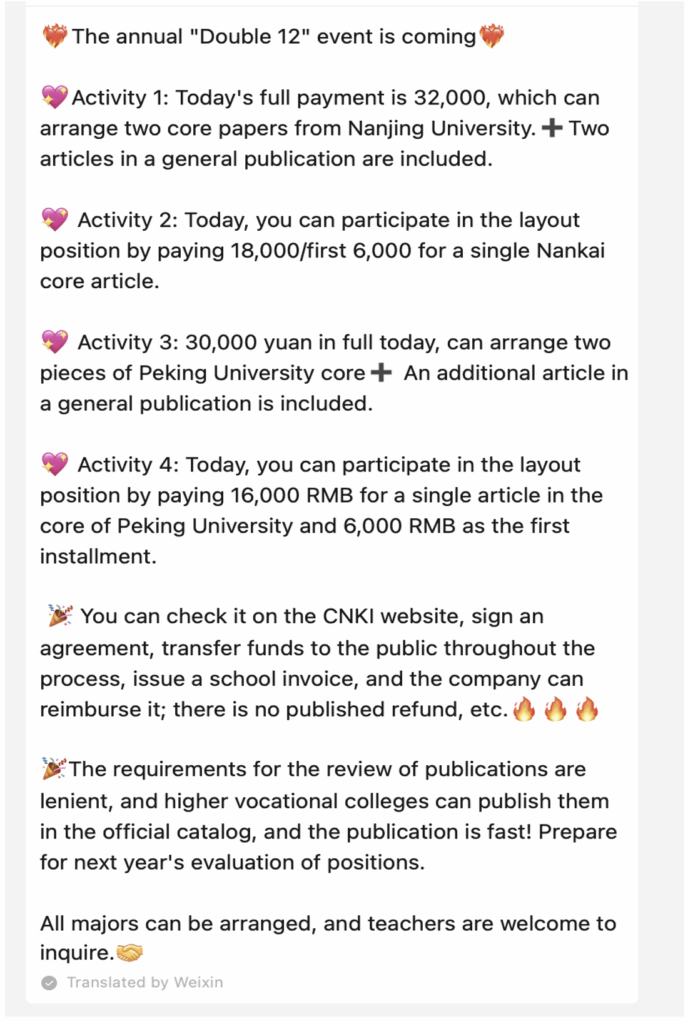

In addition to these “partnership services,” potential authors are solicited directly via social media for various pay-to-publish services. Below is a solicitation received via WeChat as the December 12th, 2024 (Double 12) shopping event approached, offering complete paper writing services, including shepherding through peer review, and revisions to publications. Out of curiosity, Alex followed up with the sender. They replied with the opportunity to prepare an article for a well-known Chinese music journal for a down payment of 5000 RMB (~ USD$700) upfront, another 5000 RMB upon acceptance for peer review, and a final 5000 RMB when the article was formally accepted and in preparation for print with a “guaranteed” publication in print by October 2025. The company claimed it had established direct partnerships with various journals for these paid placements.

Figure 1. Predatory WeChat paper mill solicitation (translated from simplified Chinese).

These two examples illustrate that companies and journals are actively partnering to author, review, and promote manuscripts and journals. Because these promotional inquiries exist, we must assume that some academic journals choose to take advantage of these services because of their pay-to-publish models, promotional needs, and the desire and pressure to boost citation counts to climb rankings tables. The motives of journals matter.

Conflicts-of-Interest and Competing Interests

The issue of motive in research is so important that many journals require conflict-of-interest disclosures. In a white paper produced for the Center for Science in the Public Interest—one that is pointed to by SAGE publishing as an exemplar on the issue—Goozner et al. (2008) write: “Since the first conflict-of-interest disclosures appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine in the early 1980s, the rationale for including this information in published scientific articles has not changed. Scientific discourse depends on objectivity. The conduct of science can be influenced by biases introduced by conflicts of interest, whether they are financial, professional, intellectual, or fueled by academic competition. The potential for bias is real, whether or not researchers believe those conflicts of interest influence their conduct” (np).

Bias is always present in research—appeals to objectivity notwithstanding—but there are surely differences between a researcher involved in emancipatory research aimed at improving the lives of a marginalized group and a researcher who stands to benefit personally (financially or otherwise) from knowledge creation that serves the interests of particular groups (industry, non-profits, advocacy organizations, and so on).[8]

As a low-status field, the stakes in music education may appear trivial compared with a much larger field like medicine. This view, however, risks overlooking not only the principles involved, but the not inconsequential amount of money involved in the music industry. Research that demonstrates improved music learning through the use of a particular piece of software, for instance, can have potentially significant financial implications for the software’s license holder(s). To the extent a researcher has no connection to anyone involved with the software and does not stand to gain in any way, one might see no ulterior motive beyond a desire to create new knowledge. If a researcher is funded by the software developer or they stand to gain in some way that might influence the conduct of the research, on the other hand, this could affect a review’s appraisal of a manuscript. One potential shortcoming of current blind peer review practices is that if authors do not declare potential conflicts of interest in the body of their manuscripts, or if a journal does not ask for these disclosures to be shared with peer reviewers, it is left to journal editors and readers after a manuscript is re-identified with its authors to make these determinations—in some cases after publication. If peer reviewers or editors are better aware of a potential conflict of interest (or the potential appearance of a conflict of interest) during review, they can take this into account in the evaluation process and make formative suggestions to the authors.

While financial conflicts of interest provide obvious examples of how motive might prove important in the evaluation of research, conflicts of interest are not always financial. As an interdisciplinary field involving aspects of the arts, humanities, and social sciences, music education involves many stakeholders besides those in industry. Those with a vested interest in the perpetuation of Western European art music, for example, may be less receptive (or even hostile) to research that (hypothetically) demonstrates superior music learning through popular musics; those with a vested interest in the advancement of Orff Schulwerk as a teaching method may be less receptive (or even hostile) to research (hypothetically) demonstrating superior music learning through Kodály. These examples can extend to include countless voluntary associations and non-governmental organizations, each with their own motives and agendas. As a statement by the World Association of Medical Editors concludes, “Professional or civic organizations may also have competing interests because of their special interests or advocacy positions” (https://wame.org/conflict-of-interest-in-peer-reviewed-medical-journals).

The idea of competing interests highlights the political nature of knowledge creation. For better or worse, peer-reviewed research is validated as real knowledge (i.e., perceived truth and reality). It is thus to the advantage of stakeholders to have their knowledge interests receive the peer-reviewed stamp of approval. Due to the precedent-oriented nature of citation practices in academic writing, achieving initial publication—i.e., getting one’s “foot in the door”—sets the stage for subsequent publications on a topic. Once research is published, it exists. This may be wonderful when motives are altruistic, but what happens if, for example, a powerful not-for-profit organization with deep financial pockets funds research to advance an agenda that serves as the basis to advance its own donor funding?[9] To what extent are editors responsible for intervening in cases where motives for knowledge creation are not disclosed or appear questionable?

The potential difference between “competing interests” and “conflicts of interest” presents an intriguing problem, one central to this special issue of ACT. At what point does a differing set of values—a competing interest—become a conflict of interest? What, precisely, constitutes a conflict of interest and what are the obligations of and mechanisms for authors to report such conflicts? Additionally, what are appropriate policies and processes for dealing with reported conflicts of interest? Is it sufficient for a journal editor to navigate the disclosure as part of the review process, or should reviewers be informed of author disclosures? What happens in cases when the reporting of disclosures compromises the principles of blind (or double-blind) review? Is it possible to ethically advance knowledge creation for an emerging practice that seeks to challenge doxa?

Current Practices in Ethical Authorship, Editorship, and Publication in Other Fields

It is not as if issues of conflict-of-interest and disclosure are new, or that the field of music education has not considered them. In comparison to other disciplines, however, music education does not appear to be as explicit or as homogeneous in its efforts. In the field of medical research, for example, international journal editors meet at least yearly to discuss emerging issues and to establish professional standards for the ethical conduct of research authorship and editing (ICMJE; WAME). The International Conference of Medical Journal Editors famously held its 1978 “Vancouver Convention,” at which were produced medicine’s first guiding principles for authorship and the ethical publishing of research, the most recent guidelines of which were updated in January 2024. No concerted effort to develop a shared set of ethical publishing standards has occurred in music education to our knowledge.

There may be wisdom to be gained through an analysis of current practices outside the field of music education, many of which have since been adopted by the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE), a non-profit organization founded in 1997 that currently has over 12,000 member journals. The COPE guidelines (which serve only as recommendations, not governance or enforcement) have been adopted by many publishers, including SAGE, the primary publication partner for many academic journals in the field of music education. SAGE publications include those published in partnership with the International Society for Music Education (ISME) and the National Association for Music Education (NAfME) in the US, and with SEMPRE in the UK.[10]

A review of the COPE website (https://publicationethics.org) on March 23, 2025 (see Table 1) reveals that only eight of twenty-five music education-related journals are COPE members. Although SAGE lists 1064 of its journals as COPE members, none of the NAfME journals[11] are listed as COPE members. SAGE’s guidelines[12] refer readers to individual journal manuscript submission guidelines for the exact policies that are active for a particular journal. For example, while COPE may recommend that all journals adopt a public-facing Conflict of Interest (COI) statement by authors, only sixteen of twenty-five music education-related journals do (see Table 1). Further, SAGE’s boilerplate language only “recommends” following COPE and ICMJE guidelines, though the eight journals on the list that are COPE members should be bound to those guidelines. In late 2024, both SAGE and Intellect updated and pushed to their journal websites new boilerplate ethical guidelines statements linked for most journals in the table below illustrating the rapidly changing ethical landscape.

An analysis of SAGE journals’ online and print publication formats shows that almost all include post-article headings for Conflict of Interest (COI) Disclosure and Funding Disclosure for recently published articles. All SAGE music education journals that publish their articles through SAGE display these disclosures at the end of each online and print article, except for Music Educators Journal (MEJ) and ISME’s Spanish language research journal Revista Internacional de Educación Musical (RIEM), which publish online and in print using custom formatting that omits these disclosures. Overall, there is a high level of variability surrounding disclosures. It is inconsistent across journals when and if disclosures are sought during the manuscript submission process, to whom these conflicts are disclosed during the peer review and editorial processes, and whether or not they must be displayed as a structural part of the online and print editions of published articles.

Only three of the twenty-five journals analyzed here currently have established explicitly stated ethics policies that exist separately from their submission guidelines. During our initial review of music education journal websites in July 2021, we found the most extensive ethics statements on the Philosophy of Music Education Review website covering many ethical concerns governing authors and editors. However, this material has disappeared in a recent website update. Other journals with explicit ethics policies separate from the recommended COPE and ICJME guidelines are RIEM and the Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education (Bulletin). Regrettably, the website link to the ethics policy for the Bulletin is currently broken, and the policy is inaccessible. The Visions of Research in Music Education (VRME) policy is quite limited, only briefly addressing the issues of dual submission, copyright, and releasing the editorial board and publishers of VRME from liability should a published article be the cause of harm.

A third layer of analysis of the websites and publication platforms for music education journals revealed that just over half of the journals analyzed publish brief author biographies along with each article. The rest list the names of the authors and the affiliations of those authors at the time of publication. A potential benefit of publishing authors’ biographies at the time of each publication is that it creates an opportunity to capture active affiliations at the time of publication and between the commissioning, design, implementation, and publication of the study. Over time, many researchers and authors switch institutions and may move in and out of other positions as practitioners or as members and leaders in advocacy, professional, or industry organizations. Requiring authors to disclose all affiliations throughout the research process is one best practice advocated in the guidelines published by WAME,[13] ICMJE,[14] COPE,[15] and the ProRes Project,[16] the latter of which explicitly guides non-medical journals in the European Union.

One of the most comprehensive disclosure documents is the form used by medical journals that are members of the International Conference of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). This disclosure form[17] (updated most recently in March 2025) requires all authors to disclose to journal editors the following information for all manuscripts submitted for publication consideration:

No Time Limit:

- All support for the present manuscript (e.g., funding, provision of study materials, medical writing, article processing charges, etc.), including all entities that all authors have had this relationship with, including if payments were made to the authors individually or to their institutions.

In the 36 months Prior to Submission, including if payments were made to the author or their institution:

- A list of all grants or contracts received by the authors (related or not to this study) over the past 36 months (even those not related to the current study)

- Any royalties or consulting fees received

- Payments or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events; payments for expert testimony

- Support for attending meetings and/or travel

- Patents planned, issued or pending; participation in a data safety monitoring board or advisory board

- Leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee, or advocacy group, paid or unpaid; stock or stock options

- Receipt of equipment, materials, drugs, medical writing, gifts or other services, and

- Other financial or non-financial interests not previously disclosed.

As a field unaccustomed to such disclosure requirements, this list may appear overly broad, too intrusive, and/or not fit for the typical research studies in music education. These requirements raise key points that our field may wish to seriously consider. Should we require all authors to be transparent regarding not only the financial aspects of how their research and broader academic work is funded, but also the potential competing interests as shown through disclosures related to leadership in professional and advocacy organizations, support received to attend conferences and for related travel, as well as other consulting fees and honoraria for speaking at events? How does non-disclosure of these potential areas of conflicting interest impact the validity and reliability of the academic scholarship advanced in our field?

While issues and tensions related to potential and actual conflicts of interest disclosures are a focus for this special issue of ACT, they are not the only ethical issues that potentially emerge or are concealed by researcher/author motives. Additional major ethical issues identified in the various guidelines referenced above relate to:

- Authorship (who should be listed as an author, including first, last and in between?)

- Editorship and Reviewership (disclosure of conflicts of interest among editors when publishing articles related to their interests)

- Professional standards of conduct (within manuscripts and during peer review, avoiding ad hominem attacks, ethical critique of ideas, declaring when a conflict of interest may result in an immediate accept or reject recommendation)

- Disclosure and corrections (to whom and when should disclosures be made? To the editors and/or reviewers? How are corrections and disclosures best made, especially after online and print publication, and in external indexes and platforms?)

It is not as though our field has never considered authoring, reviewing, editing, and publishing issues. Still, far too often, in our experience at least, such discussions tend to occur informally between colleagues rather than through formal publishing—something that helps to keep opaque what should be transparent. Times may (or may not) be changing, however. A recent study by Schultz et al. (2024) examining career readiness among doctoral alumni, for example, found that opportunities reported during coursework included submitting a paper for publication in a music education research journal (57% of respondents) or a practitioner journal (36% of respondents). Unfortunately, the study does not appear to have asked questions about peer review experiences, mentorship, or development. Conversely, a recent survey of music education faculty by Koner and Gee (2024) did include questions about publishing experiences. Surprisingly, based on the number of anecdotal stories in music education about negative peer review experiences, they reported that 46.4% of respondents had positive peer review experiences; only 5.6% reported having negative experiences. One of the qualitative responses in their study is revealing, however, and speaks to one of our motivations in wanting to coordinate this special issue of ACT: “I wish we provided training/mentorship for reviewers as I often feel that folks just starting out feel a need to ‘prove’ themselves in the review, which leads to a large amount of suggested revisions that don’t actually make a huge difference” (Koner and Gee 2024, 13).

To spark further conversation and debate around authoring, reviewing, editing, and publishing, we invited a selection of current and former music education journal editors to join us in contributing to a special issue of ACT aimed at surfacing the motives and tensions that underpin the ethical conduct and communication of research in our field. We invited submissions that not only offer critique and analysis, but that also (to the extent possible) present real-world examples from or adjacent to our field, narratives of personal experiences navigating these issues as authors and/or editors, as well as recommendations for specific frameworks, guidelines, and policies that music education journals may want to adopt to address these issues.

As readers no doubt recognize, there is an inherent tension in the idea of inviting authors to write on the topic of the ethics of authorship and editorship ethics for a peer-reviewed journal. To be transparent about the process, we compiled a list of current and past editors of journals in music education and closely adjacent fields. We then attempted to curate a list that balanced various considerations (geography, gender, and so on), inviting individuals from the curated list to contribute chapters. The intent was to ask other names on the complete list and invite shorter contributions in response to one or more of the main articles. The personalized nature of the submitted articles did not allow for double-blind peer review. As a result, we followed a single-blind protocol. As one might imagine, this was delicate business, as peer review involved critiquing the work of colleagues who are current or former journal editors. In three cases, reviewers chose to reveal themselves to the authors, allowing for the kind of author-reviewer dialogue alluded to in three of the contributions in this special issue.

The issue leads off with Roger Mantie’s consideration of mentorship (or lack thereof) in authorship, reviewership, and editorship and the relationships that exist—or ideally should exist—between authors, reviewers, and editors. Patrick Schmidt’s article extends the examination with a thorough interrogation of the “legibility” of peer reviewing developmental practices, especially as these may be refracted through claims of professionalization. The next two articles in the issue raise questions about status, genre, and audience. Michele Kaschub and Katherine Strand offer perspectives on reviewing practices in practitioner journals. They critique how many of the field’s practitioner journal review board members may not always be operating in the best interests of contributing authors and the journal’s intended audience due to their graduate training and faculty proclivities. José Luis Aróstegui’s contribution similarly addresses questions of audience and power differentials, but from the perspective of someone instrumental in initiating and developing Revista Internacional de Educación Musical, the field’s first Spanish-language journal. Among the issues Aróstegui raises are Article Processing Charges and equitable access to knowledge. In the final article in the issue, Pamela Burnard and Elizabeth Mackinlay draw on the work of Karen Barad to offer a posthumanist reading of ethics in music education research. Their intricate examination of what it means to care in research is a critical reminder not to lose sight of why we presumably got into this business in the first place. The issue concludes with shorter response articles from Liora Bresler responding directly to Patrick Schmidt’s contribution and more general responses from Joseph Abramo and Alexis Kallio, whose perspectives offer additional critical thoughts on various aspects of authoring, reviewing, editing, and publishing.

We hope this special issue serves in part as a catalyst to more extensive and deeper conversations across the field of music education related to ethical issues in publishing. For us, we find it helpful to look beyond the top layer to surface and examine the various (and at times competing) motives among all of our stakeholders. Through taking greater care to disclose our conflicts, motives, and processes within and around our research and scholarship, we can aim at a higher level of transparency as our field navigates these challenging times. For now, we leave you with the following questions to further seed our collective conversations around these important issues:

Key Tensions and Questions for this Special Issue and Beyond

- What ethical principles and motivations might our journals’ publication policies surface for disclosure and consideration by editors, peer-reviewers, and readers?

- Are conflicts of interest inherently bad? What might be guiding principles for emancipatory and participatory research traditions where an “insider” perspective is considered valuable? How might authors ethically move from the shadows of blind review to transparency?

- How might journals support emerging, participatory, and emancipatory research methods where closeness to the phenomena under study is seen ontologically as a positive rather than a negative characteristic? What is the role of motive and conflict of interest disclosure for these methods of research?

- How might our field better surface the motivations behind our research studies, agendas, and publication strategies? Why is this research being conducted and who does it potentially benefit?

- What are the relationships among the researcher and those being researched? When might constitute an abuse of such relationships?

- What are the benefits of blind versus open review? What can be missed by the current blind review process? What might be gained by emerging open/transparent review processes?

- What guidelines might better support scholarly discourse among authors and reviewers? What ethical principles and frameworks might be formally instituted by journals in our field (e.g., PMER)?

- What are the ethical tensions and issues currently faced by journal editors in music education? How might editors work to advance and provide pathways for emerging research traditions and approaches that challenge the status quo (e.g., emancipatory, participatory traditions)?

| Journal Title | Scope/

Focus |

Affiliated Organization | Publisher | Sub-mission Guide-lines | Ethics Policies | COPE mem-ber | COI | Fun-ding | Bios |

| International Journal of Music Education | International, open topics | International Society for Music Education (ISME) | SAGE | Link | COPE, ICMJE, SAGE | YES | YES | YES | NO |

| Journal of Research in Music Education | International, open topics | NAFME (US), SRME | SAGE | Link | COPE, ICMJE, SAGE | NO | YES, but not in guide-lines | YES, but not in guide-lines | YES |

| Research Studies in Music Education | Inter-national, open topics | SEMPRE (UK) | SAGE | Link | COPE, ICMJE, SAGE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education | Inter-national, open topics | CRME, University of Illinois Press | JSTOR | Link | CUST-OM & Univ. of Illinois Press | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Music Education Research | Inter-national, open topics | Indepen-dent | Taylor and Francis | Link | T&F | YES | YES | NO | YES |

| Action, Criticism, and Theory in Music Education | Inter-national, open topics | Mayday Group | Indepen-dent | Link | NONE | NO | NO | NO | YES |

| Journal of Music Teacher Education | Inter-national, open topics | NAFME (US), SMTE | SAGE | Link | COPE, ICMJE, SAGE | NO | YES | YES | NO |

| Journal of Historical Research in Music Education | Inter-national, topic-based | Indepen-dent | SAGE | Link | NONE | YES | YES | YES | NO |

| International Journal of Community Music | Inter-national, topic-based | Indepen-dent | Intellect | Link | COPE | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| Journal of Popular Music Education | Inter-national, topic-based | Ass’n for Popular Music Education | Intellect | Link | COPE | NO | YES | YES | NO |

| Journal of Music, Technology, and Education | Inter-national, topic-based | Indepen-dent | Intellect | Link | COPE | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| International Journal of Choral Singing | Inter-national, topic-based | American Choral Directors Association | ACDA | Link | NONE | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Philosophy of Music Education Review | Inter-national, topic-based | Indepen-dent | Indiana Univer-sity Press | Link | NONE | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| British Journal of Music Education | Regional-national focus, open topics | Indepen-dent | Cam-bridge U. Press | Link | ICMJE -adapted & Cam-bridge University Press | YES | NO | NO | NO |

| Journal of General Music Education (formerly GMT) | Regional-national | NAFME (US) | SAGE | Link | COPE, ICMJE, SAGE | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| Nordic Research in Music Education | Regional | Nordic Network of Music Education Research | NOASP | Link | NONE | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| Revista Internacional de Educación Musical, | International, language focus | Inter-national Society for Music Education (ISME) | SAGE | Link | CUSTOM | YES | YES in guidelines | YES in guidelines | YES |

| Visions of Research in Music Education | Regional (state) | Indepen-dent | Univer-sity of Connect-icut Digital Com-mons | Link | Limited CUSTOM | NO | NO | NO | YES |

| ABCD Choral Research Journal | Regional (national) | Assn. British Choral Directors | Indepen-dent | Link | NONE | NO | NO | YES | NO |

| Finnish Journal of Music Education | Regional (national) | Finnish Society of Research in Arts Education and the Hollo Institute | UniArts Helsinki | Link | FABEI | NO | YES | YES | NO |

| Music Educators Journal | Regional (national) | NAFME (US) | SAGE | Link | COPE, ICMJE, SAGE | NO | YES | YES | NO |

| UPDATE: Applications of Research in Music Education | Regional (national) | NAFME (US) | SAGE | Link | COPE, ICMJE, SAGE | NO | YES | YES | NO |

| Journal of the Association for Technology in Music Instruction | Regional (national) | ATMI | Univ. of Tennessee | Link | NONE | NO | NO | NO | YES |

| College Music Symposium | Regional (national) | College Music Society | Independent | Link | COPE, CMS | NO | NO | NO | YES |

| Psychology of Music | Adjacent or Arts Education | SEMPRE (UK) | SAGE | Link | COPE, ICMJE, SAGE | YES | YES | YES | NO |

| International Journal of Education and the Arts | Adjacent or Arts Education | Independent | Independent, Penn State | Link | NONE | NO | NO | NO | YES |

Table 1. Matrix of 25 music education journals’ ethics disclosure and manuscript submission policies and practices (data accurate as of March 23, 2025).

References

Beshyah, Salem, Wanis Ibrahim, Elhadi Aburawi, and Elmahdi Elkhammas. 2022. The rules and realities of authorship in biomedical journals: A cautionary tale for aspiring researchers. Ibnosina Journal of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences 10 (5): 149–57. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmbs.ijmbs_62_18

Burnard, Pamela. 2006. Telling half the story: Making explicit the significance of methods and methodologies in music education research. Music Education Research 8 (2): 143–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613800600827730

Chapman, Colin A., Júlio César Bicca-Marques, Sébastien Calvignac-Spencer, Pengfei. Fan, Peter J. Fashing, Jan Gogarten, Songtao Guo, Claire A. Hemingway, Fabian Leendertz, Baoguo Li, Ikki Matsuda, Rong Hou, Juan Carlos Serio-Silva, and Nils Chr. Stenseth. 2019. Games academics play and their consequences: How authorship, h-index and journal impact factors are shaping the future of academia. Proceedings of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences 286 (1916): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.2047

Goozner, Merrill, Arthur Caplan, Jonathan Moreno, Barnett S. Kramer, Thomas F. Babor, and Wendy Cowles Husser. 2008. A common standard for conflict of interest disclosure. Center for Science in the Public Interest. https://www.cspinet.org/sites/default/files/attachment/20080711_a_common_standard_for_conflict_of_interest_disclosure__final_for_conference.pdf

Kelly, Jacalyn, Tara Sadeghieh, and Khosrow Adeli. 2014. Peer review in scientific publications: Benefits, critiques, & a survival guide. EJIFCC 25 (3): 227–43.

Koner, Karen, and Jennifer Gee. 2024. Publishing preparation, experiences, and expectations of music education faculty in higher education. Journal of Research in Music Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224294241285323

Kuhn, Thomas S. 1962. The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Lather, Patricia Ann. 1991. Getting smart: Feminist research and pedagogy with/in the postmodern. Routledge.

Pfleegor, Adam G., Matthew Katz, and Matthew T. Bowers. 2017. Publish, perish, or salami slice? Authorship ethics in an emerging field. Journal of Business Ethics 156 (1): 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3578-3

Schultz, Elizabeth S., Ian W. Miller, Charles Oldenkamp, Julie M. Song, Troy R. Thomas, Kristina R. Weimer, Nathan B. Kruse, and Martina L. Miranda. 2024. An examination of career readiness among music education doctoral alumni. Journal of Music Teacher Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/10570837241295756.

[1] See https://retractionwatch.com and https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-00212-1

[2] Or, in the verbiage of neoliberalism, universities are considered a “knowledge enterprise” (e.g., https://research.asu.edu).

[3] https://www.vox.com/2015/12/7/9865086/peer-review-science-problems

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/05/upshot/peer-review-the-worst-way-to-judge-research-except-for-all-the-others.html

[5] The current political situation in the United States notwithstanding.

[6] It should be noted that, due to poor wages in some academic sectors, paid opportunities beyond one’s university salary can be more a matter of necessity than greed. There is an economic justice argument to be made here, creating additional layers of complexity to the ethics of knowledge creation.

[7] One is reminded of the Alan Sokal hoax, except in this case the supposed manuscript does not appear to be motivated by a desire to expose scholarly standards but to take advantage of an exploitative system in the academic publishing world.

[8] In a 2006 editorial for an issue of Music Education Research, Pamela Burnard argues for the ethical importance of disclosing what she describes as the distinct aspects of method, methodology, and theoretical perspective. Burnard’s argument is addressed more to the transparency of how research is reported in music education than the issue of motive we are advancing here, but Burnard’s point is well-taken: the failure to disclose method, methodology, and theoretical perspective can result in a reification of knowledge creation by hiding it behind a veil. See Burnard (2006).

[9] See this COPE case study for a related discussion of issues beyond financial conflicts of interest: https://publicationethics.org/case/undisclosed-conflict-interest.

[10] i.e., International Journal of Music Education, Journal of General Music Education, Journal of Historical Research in Music Education, Journal of Music Teacher Education, Music Educators Journal, Psychology of Music, Research Studies in Music Education, Revista Internacional de Educación Musical, UPDATE: Applications of Research in Music Education, Music Education Research,, and Psychology of Music.

[11] Journal of Research in Music Education, Music Educators Journal, Journal of General Music Education, Journal of Music Teacher Education, UPDATE: Applications of Research in Music Education.

[12] https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/declaration-of-conflicting-interests-policy

[13] https://wame.org/conflict-of-interest-in-peer-reviewed-medical-journals

[14] http://www.icmje.org/icmje-recommendations.pdf

[15] https://publicationethics.org/

[16] https://prores-project.eu/

[17] https://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/